The gossipiest, most divisive and arguably most compelling literary legend of them all — “the plot of the suicidal poetess and her abandonment by the man with the witty mouth,” to quote Janet Malcolm — is turning 50. It was on February 11, 1963, that 30-year-old Sylvia Plath, having first sealed up her young children’s bedroom with tape and towels, went into the kitchen of her London flat and gassed herself. Thus began the American poet’s deification as a feminist martyr and an ongoing conflict of Biblical fervor. On one side stand those who place culpability for Plath’s suicide squarely on the head of her husband, the late English poet Ted Hughes. The other side, equally intransigent, blames her innately tortured psyche, which had led to at least one prior suicide attempt.

Hughes’ murderous crime, to those who view it as such, is clear-cut: Six years after the couple’s epochal first encounter at a Cambridge University party in 1956 — he’d kissed her “bang smash” on the mouth, she’d bitten his cheek and drawn blood — Plath’s “big, dark, hunky boy,” the demigod of her teenage fantasies, destroyed their marriage by taking up with another woman, the austerely beautiful Assia Wevill. The case against Hughes was strengthened when, after another six years had passed, Wevill killed herself and their 4-year-old daughter, bizarrely by the same method of gas and, apparently, at least partly driven by his philandering.

Evidence for Hughes’ defense can be found in the career frustrations experienced by Plath during her final months. Her erstwhile soul-mate’s betrayal tapped a deep well of creative inspiration, and the raging, revolutionary, self-excavating poems from that period — including “Daddy” and “Lady Lazarus” — would eventually help canonize their creator as one of the major poets of the 20th century. Yet, at the time they were rejected as “too extreme.” Meanwhile, Plath’s gauche, coruscating first novel, “The Bell Jar,” a barely fictionalized account of her stint as a Mademoiselle guest editor and subsequent grim descent into depression, failed to find an American publisher; “disappointing, juvenile and overwrought” was one damning verdict.

Also currently celebrating its 50th anniversary, “The Bell Jar” was released in the UK in January 1963 under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas, a precaution insisted on by Plath to save her mother embarrassment. Alas, initial reviews were less than laudatory. A few years after Plath’s death, Hughes — the legal executor of her literary estate, even though they were bitterly separated — let the novel be published under her own name, triggering a flurry of renewed interest. Then in 1971, scandal of scandals, he wanted some money to buy a country house, so he finally allowed “The Bell Jar” to be published in the U.S. It was an instant and critically acclaimed best-seller. Now one of those rare cultural artifacts with a life force all its own, “The Bell Jar” — whose narrator, Esther Greenwood, is mired in existential agony on finding that neither herself nor the world meet her starry-eyed expectations — is taken up as talismanic by each new generation of readers.

In the years following her death, Plath also became that most oxymoronic of entities: a commercially successful poet. “Ariel,” her second collection of poems — her first, "The Colossus and Other Poems" had been published in 1960 — sold an incredible 15,000 copies in its first 10 months of publication in the UK. Substantially edited by Hughes, who added and removed poems and changed their sequence, the arrangement of “Ariel” was a focal point in the first wave of contention surrounding his self-serving manipulation of Plath’s literary legacy. (A “restored edition” of “Ariel,” with the collection exactly as Plath had composed it, was published in 2004.) After all, if his intentions were honorable, the argument goes, he wouldn’t have destroyed her journal that covered the final months of their relationship — nor appointed as the estate’s literary agent someone who, as he was well aware, hated Plath with a passion: his formidable, possessive sister, Olwyn.

Indeed, not one book about Plath has been written without Olwyn — herself becoming a legendary figure, bestriding Colossus-like over the dominion of her brother’s reputation — intimidating, placing injunctions and threatening to withhold permission to quote from poems if conditions aren’t met. “No mention of Assia allowed, for example,” marveled early biographer Linda Wagner-Martin. “Well, then the separation just looked like Sylvia had lost her mind.”

Frieda Hughes, Plath’s daughter and now the estate’s literary executor, also gets into periodic tussles over what she sees as the rampant, shameless feeding on her mother’s life and work. When the Gwyneth Paltrow biopic, “Sylvia,” was made by the BBC in 2003, Frieda banned them from using Plath’s poetry and published a poem, “My Mother”: "Now they want to make a film/For anyone lacking the ability/To imagine the body, head in oven/Orphaning children." Yet as Kate Moses — a former Salon editor, and the author of "Wintering," an acclaimed novel about Plath’s last days — has pointed out, it is precisely the enduring appetite for all things Plath that provides Frieda with considerable financial comfort.

The saga’s latest episode involves Elizabeth Compton Sigmund, who was a friend of Plath’s and, with her husband, the original dedicatee of “The Bell Jar.” Interviewed by The Guardian’s Sam Jordison, Sigmund has reiterated several points deemed strictly off-message by the Hughes faction, including that the last straw for Sylvia was hearing of Assia’s pregnancy, and that after Sylvia’s death, a “guilt-ridden” Hughes said: “It doesn’t fall to many men to murder a genius.” Needless to say, Olwyn has taken characteristically voluble exception to Sigmund’s words: “The nonsense that has continued to be written about the story is shocking to me,” she told Jordison. “Sylvia wasn’t the innocent victim, or half so helpless as she’s been made out to be. You just have to look at some of her poetry … She was vicious and a little bit crazy.”

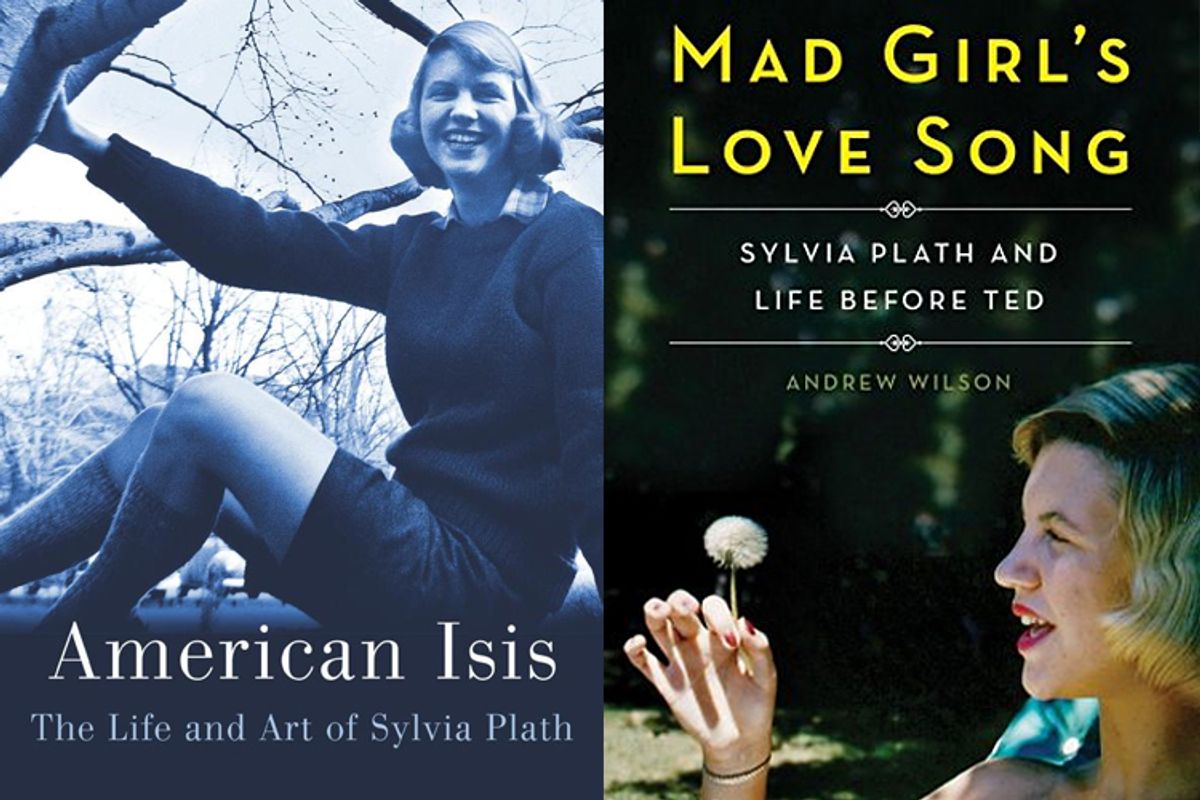

Entirely contrary to Olwyn’s wishes, these endless controversies only serve to glorify the Plath mythology, whose seductive lure to authors and critics never seems to fade. Two new biographies are accompanying the dual 50th anniversaries of the publication of “The Bell Jar” and Plath’s death: “American Isis: The Life and Art of Sylvia Plath” by Carl Rollyson and “Mad Girl’s Love Song: Sylvia Plath and Life Before Ted” by Andrew Wilson. Wilson’s thoughtful and well-researched study, a compendium of Plath’s many lovers from the pre-Ted days — including Richard Sassoon, who’s officially sanctified as The One Who Got Away — persuasively submits that the seeds of Plath’s self-destruction were sown long before she met her husband, joining such influential Plath-Hughes exegeses as Janet Malcolm’s "The Silent Woman" on the “not Ted’s fault” side. Rollyson’s more conventional biography, a lively whistle-stop tour of all the significant landmarks in its subject’s short life, is consummately written and worth reading for the final chapter alone: “In the Temple of Isis” is a gripping account of the feuds that occurred between the Hughes camp and various writers, as Ted and Olwyn endeavored to foreground their version of history and rebut the narrative featuring Ted as the murdering brute.

Just as Plath dwelled on the newly widowed Elizabeth Taylor stealing Eddie Fisher from poor Debbie Reynolds (“How odd these events effect one so!” she wrote in her journal), the debate over whether Ted was the villain and Sylvia the victim, or vice versa, has exercised many literary minds over the years. A.S. Byatt, the Booker-winning novelist more renowned for her dazzling intellect than her penchant for tittle-tattle, once confided to the New York Times:

I’m automatically on [Ted’s] side about Sylvia Plath. When I knew her, it was during her most writing-for-Mademoiselle-ish days, and she had bobby socks and totally artificial bright red lips and totally artificial bright blond hair, and I remember her as a made-up creature with no central reality to her at all, always uttering advice like a woman’s magazine advice column. She wrote beautiful words, but there wasn't anybody inside there. I’m sure he behaved very badly, but I regard it as automatic that anyone married to Sylvia Plath would have to find someone else in the end, because I don't think she was a complete person.

Hughes’ final collection of poems, "Birthday Letters," published shortly before his death in 1998, invites the reader to see Plath as Byatt did, and it marks a crowning, valiant attempt at exoneration in the court of public opinion. The book, an international best-seller, didn’t so much have its intended effect as provide grist to the mill of speculation, more evidence to weigh in the apportionment of guilt and innocence. Novelist Fay Weldon, for example, was unswayed, finding space in her autobiography, "Auto da Fay," to assert that Plath died “for love … not depression, let alone ‘born to suicide’ as is so often said of Sylvia.”

What no one can dispute, though, is that Plath would be thrilled to witness the intricacies of her life still drawing fascination 50 years on: More than anything else, she longed to be famous, immortal, celebrated. Hughes once complained that scholarly interest in Plath was motivated by “curiosity of quite a low order, the ordinary village kind, the bloodsport kind.” But she instinctively knew that only by taking herself as the sole subject for her art, before the term “confessional poetry” had even been coined — and way in advance of our current preoccupation with the whys and wherefores of writerly oversharing — would she attract the level of attention she craved.

She was right, of course: Not only has Plath’s small oeuvre spawned an ever-flourishing worldwide industry of biographical interpretation, but her writing so seamlessly fused self-obsession with an otherworldly gift for language that, on reading, it’s impossible to differentiate between scholarly interest and “curiosity of quite a low order” in one’s mind. This entrancing quality, this perfect, irreproducible formula of unadulterated narcissism and true genius, is what sustains her place in the spotlight just as much as the posthumously self-perpetuating Plath-Hughes soap opera. So it is that the defiant mantra of Plath’s alter-ego, Esther Greenwood, not only echoes through the ages but regularly gets tattooed on young women’s skin:

I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart.

I am, I am, I am.

Shares