At 1:57 I stumble out of the underground and run up the street in budding frost and blinding light. Only one minute late. What’s my best excuse — one that makes me sound normal, charming, not frantic? This is my second test, a second round of interviews. I hope I get the job.

My name is called; I follow the name-caller into a small room. A pleasant, bright, but not overly warm blonde woman says hello and introduces herself. I am asked to undress and put on a gown with the opening and ties in front. I step out from behind a curtain, hoist myself upward, place my ankles in the stirrups, and scoot my behind to the edge of the papered table as I’ve been told. I am asked a few initial questions and told that I’ll feel pressure. Meanwhile, a sterile, phallic-shaped object is inserted into my vagina.

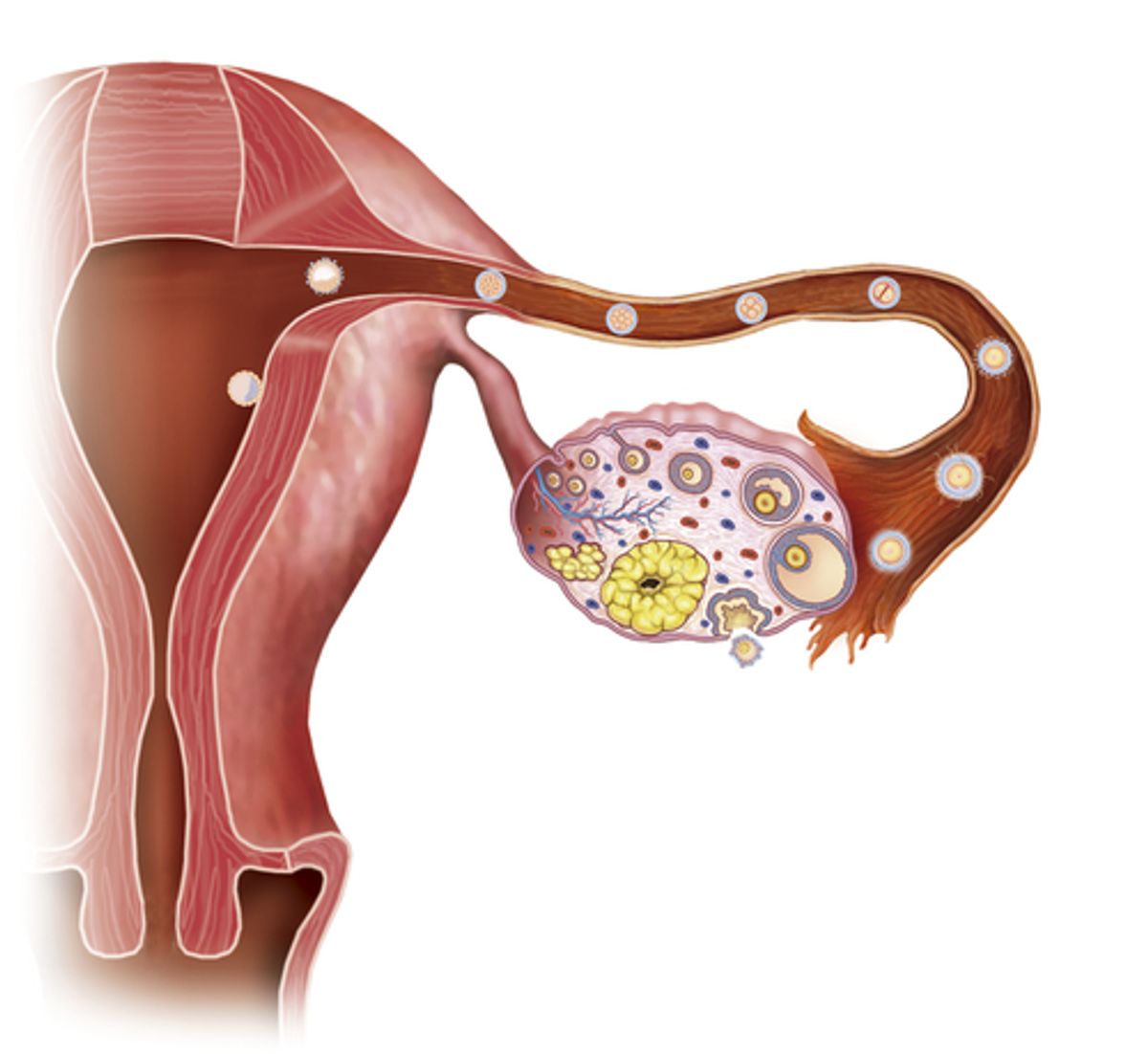

There are my ovaries on the screen to my left. I’d passed a first test already; my organs are what I’ve come to have interviewed today. The blonde woman, a doctor, points to the screen and explains how my insides stack up against her ideal uterine candidate. I twist my neck to see. She tells me I have 18 follicles on the right side, 21 on the left.

There are my ovaries on the screen to my left. I’d passed a first test already; my organs are what I’ve come to have interviewed today. The blonde woman, a doctor, points to the screen and explains how my insides stack up against her ideal uterine candidate. I twist my neck to see. She tells me I have 18 follicles on the right side, 21 on the left.

“And what does that mean?” I ask.

“That’s good,” she affirms. “That means we can get a lot of eggs out of you.”

My follicles appraised, I am released. I put my clothes back on and walk out of the fertility clinic’s exam room, one of many hosted by this well-established, reputable institution. After the ultrasound, I am told to go and sit tight in an olive green chair, where I wait to have my blood taken.

“What’s this for?” I ask the nurse who comes over to me. I put my hand in a fist as she instructs, looking at her rather than at my arm.

“I’m glad you asked,” she says. “Most people don’t.”

She mumbles something and I nod, pretending to understand. I’m recovering from a fever that I haven’t shaken off. I’ve tried to work straight through it — as a freelancer, I don’t get sick days. She gives me a form and a few instructions, which I listen to, but again don’t really hear. I ask her to clarify what I’m signing for, and she repeats: “Genetic testing. They’re testing your blood for diseases,” she explains.

She turns cold when I start filling out the part of the form that asks for a name and address: “You’re just a donor! They don’t need to know who you are.”

My form is yanked away and she slaps down a new one. “You’d better sign the back of this first. In case you forget again.”

I try to tell her I am slightly confused because I am still recovering from a fever. She doesn’t respond. I want to explain that I have this fever because, like her, I work too hard, because I collect jobs paid and unpaid like heavy charms on a bracelet I display to anyone who asks with confused pride. The shiniest weighs me down the most, but it pays nothing.

I can’t stop to get well because I live and work in New York City, and that’s the market reality for our bodies here. I want to add “egg donor” to my chain, to display this most recent job with intrigue, shame, and a story to tell. Not to mention the huge paycheck.

I want to tell her that I am beyond sick — I am looking for cures in easy money and bought time; I’m ready and willing to sell my body parts to get better. Instead, I apologize for being less functional than usual. She doesn’t care, or doesn’t listen. She’s trying to work, too, to make a wage and a living, and I’d messed up the precariously smooth operation of her day.

I fill out the form, careful not to include any of my human codifiers: name, to tell something of my ancestry; area code, to tell from which aspiring part of the country I fled in favor of New York; address, to show where I landed, what I can afford on a freelance editor, writer, researcher, and tutor’s salary. I sign the back of the form and a small card with a butterfly on it, which grants permission for my genetic makeup to be anonymously tested and, perhaps, deemed passable. I clench my fist and watch the blood squirt into a vial.

The nurse doesn’t smile; she barely acknowledges my thanks and goodbye. I’m sure I’ve made a grave error and won’t be hired. I’d shown that I wanted to be acknowledged, named, humanized. Exiting the clinic I wonder vaguely if my blood is diseased, marked by unknown genetic failures absorbed through centuries of pairings, mixings, births.

By 2008, well over 100,000 American women donated their eggs to fertility clinics.

Donated — as in, “compensated donation.” In some states and countries, egg donation for medical research or uterine insertion remains legally uncompensated. As a result, almost no one volunteers to undergo the risky, time-intensive procedure. Having high doses of fertility drugs containing hormones injected into the skin on a daily basis, then allowing a highly skilled surgeon to relieve the over-stimulated ovarian follicles of their eggs isn’t exactly something that can be advertised on craigslist under "no compensation" — but … we can provide unparalleled experience and great contacts!

New York law states a woman cannot “sell” her eggs, but can “donate” them for between 5 and 10 thousand dollars. The language at the fertility clinic I contacted was very specific: It is illegal for oocyte donors to sell their eggs. Young women who donate anonymously receive $8,000 in compensation for their time, risk, and effort in donating their eggs. They explain that all costs will be covered: medical, pharmaceutical, and psychological.

Most “donors” are in college (women must be at peak fertility, or between 21 and 30, to donate) or otherwise young, fertile, and in need of financial relief. Some are recruited for their special qualities. Are you tall? Blonde? Jewish? Egg donation is unchecked by many restrictions that apply to other types of employment. This is not an equal-opportunity situation.

The week before the ultrasound, I’d come into the fertility clinic to sit in a tiny room with no windows and write out everything I knew about my health and family history. This information was to go, anonymously, into a profile that potential egg-seeking “matches” could use to find their closest genetic match. My grandmother’s weight, my mother’s blood pressure level, the color of my grandfather’s eyes and the year of his immigration from Denmark. The cause of death for Eileen, Albert, Bent, and Peggy, names removed. I was asked to list the qualities I admired most in my mother, the kind of emotional atmosphere I was raised in. I was asked to list my favorite book and why, where I’d like to be professionally in five years, the details of any past pregnancies, my favorite movie and why.

Just don’t write “Battle Royale,” I told myself, over and over. Don’t. Make yourself look sweet; intelligent, honest, pliable, ambitious, and motherly. Capital-F Female. Put your best qualities forward.

This was little different from the scores of job applications I’d filled out since graduating college two years ago but for the additional intimate queries. What are your best and worst qualities, and how many sexual partners have you had over the last six months?

Year? Anal sex? Drug use?

Writing these things was one form of embarrassment; speaking them aloud felt different. After the first round of vetting and the physical exam, the questions continued. Had I ever been pregnant? The blonde doctor asked, glancing at my chart, where the answer to this question was already clearly written.

“Yes,” I confirmed.

“Tell me about that,” she pried. I stopped. In any other job interview, how would I handle this? What did the self-help bloggers say? Turn it into a positive! Shift the focus on negative experiences and focus on the lesson you learned, the positive qualities you gained!

How to (the Google search begins) condense the most concrete, the most painful, the most jarring experience of my 25 years into something simple, calm … positive? How to simplify weeks of agonizing back and forth on what to do with the life I’d accidentally started, the nauseating mix of trauma and gratitude of a legal abortion, the confusion of how to speak privately or publically about the taboo yet commonplace procedure in a palatable response? I was in a clinic, I reminded myself, not an editor’s office. But I was, after all, under scrutiny. I wanted the job.

I tell her I was pregnant last year, and it ended in a termination. Should I add, “At least I know I’m fertile!” Or, “I still feel wretched every day but want to use that experience to help out another couple!” Or perhaps a joke: “Well, it was the only possible promotion from my job as a nanny, and I guess my uterus is as competitive as I am!”

I settle on “There were no complications.” I swallow and think about the compensation for donation: $8,000. I think about freedom from debt, about months of rent for my Queens apartment paid off, about a moment’s rest. Maybe I could cut out one of my five jobs. Maybe I’d do so well I’d be promoted and could donate more eggs; make more money. I thought about not having to ask my overworked mother for help, starting a savings account, paying her back.

Some egg donors have dealers who act like agents for novelists or actors. The boutique clinics or private “brokers” who offer upwards of 20, 30, or even 60,000 per harvested cycle are only interested if you are over 5’9”, Caucasian, and measurably above average in looks and intelligence. Ivy league education a plus. Sometimes, if you are the right brand of “exotic,” (ads I saw most frequently asked for Jewish or Asian would-be donors) being outside of this model can earn you more money.

But of course, we live in America, where choice, and the ability to buy choice, rules. The demand for the purchasable experience of pregnancy is high. The more money offered, the more discriminating one’s taste can become. As with other markets centered around the buying and selling of poorer humans and their parts, the greatest risk goes to the seller — the one whose body is up for rent.

Yet, as I found so attractive, egg donation is one of the few jobs in this economy where there are more positions for women workers than there are jobs themselves. According to Dr. Mark Sauer, director of the Center for Women’s Reproductive Care at a large research university, “Women aren’t exactly lining up [...] There are a lot more recipients than donors.”

Dr. Sauer’s observation isn’t so surprising. The short-term risks of egg donation include discomfort, nausea, weight gain of up to 10 pounds in 3-5 days, irritability, abdominal pain, mood swings, and arterial thrombosis. From the egg retrieval itself -- which sees the donor under anesthesia and involves the insertion of a very thin metal tube in the vagina, up through the cervix, and into the ovaries where the overproduced eggs fill a treated woman’s follicles -- a woman risks potential bleeding, infection, damage to the ovaries or bowel and bladder, and the ominous, sweeping risk of “persistent psychological problems.”

Longer-term risks are fairly mysterious, but in some cases or studies, donation has been linked to cancer, infertility, and death. “Yet,” according to a helpful bioethics wiki on the subject, “not allowing women to donate eggs would be inappropriately controlling and would breach the bioethical principle of autonomy and self-determination.”

I read about one woman whose autonomy and self-determination inspired her to sell her eggs for years as a primary form of income. Eventually, her donor turned on her. She sold her story as a book, since everyone, especially mid- and post-recession, loves a good egg donation story — almost as much as a good betrayal. As is the case with anyone on the liminal, somewhere-near-last pecking order of the body-capital market, some egg donors have stories saturated with the potent mixture of pain, curiosity, and pleasure that drives the late capitalist entertainment market.

As documented in medical studies, comments on blogs, and especially in a documentary called "Eggsploitation," the profession’s extreme occupational hazards include severely distended abdomens, emergency removal of swollen ovaries, and hospitalizations -- all paid off by the clinics but literally scarring and in some cases more than that. Then there are the unproven cases that link donation to death by ovarian, breast, or other cancers. The expenses of longer-term affects, forgotten after the anonymous donor ends her last cycle and the expectant parents either birth or do not birth the child that is now legally theirs, are probably not covered by the fertility clinics.

Other donors speak joyfully on blogs or forums of their chosen side profession and the children (known and unknown) that their eggs produced, expressing fulfillment at the idea that they were able to make the dream of parenthood for a non-conceiving heterosexual couple, single woman, or homosexual couple come true. Just count the exclamation points in one of AltruiDonor’s blogs by pressing the link below:

[embedtweet id="266095823480299520"]

There’s nothing inherently wrong with egg donation, according to the laws of New York State and of America. But many believe otherwise. In documentaries like "Eggsploitation," the argument is that the practice is predatory, market-driven, and ultimately extremely harmful to the donors.

Catholics do not condone in-vitro fertilization unless it occurs between one man and one woman united in holy matrimony — no outside parties. IVF is condemned even within a marriage if the sperm is gathered through masturbation. In the Bible, Sarai, Hagar, and Abraham suffer immensely from an ancient form of egg donation. For Jews, it’s more complicated still, with rabbinical voices weighing in on both sides of the maternity question: If a child comes from a donated egg, who is the “real” mother? Does the Jewishness of the child rest in the egg, or the gestational womb? In Islam, egg donation is generally rejected.

Outside the perspective of the sacred texts, in the field of bioethics, donation is not condoned, nor is it necessarily seen as pure evil. It has been, however, likened to selling other organs on the black market, or to genetic testing on populations that are poor and undereducated.

According to a study authored by a physician mother calling for follow-up on her daughter’s post-donation colon cancer, of the American women who sold their eggs as of 2008: “Few would have received enough information for them to make an informed decision. Most would not have understood that there is a huge difference between being told, 'We don’t know of any significant long-term risks' and 'There are no significant long-term risks.'" Aside from the cancers and death mentioned previously some “significant” risks cited by bioethicists include but are not limited to: the commodification of human life, compromised issues of identity, and the risk of women not selected to be donors facing a risk to their psychological self-identity.

We want our biological makeup to be desired. It’s hard enough feeling genuinely wanted as a young woman roaming New York City in search not just of success, but also love and sex. To hear “confirmation” from a medical professional that your genetic makeup is inferior could very well be worse for a young woman’s self-confidence than receiving a Facebook message along the lines of “Hey, I just think you should know, I’m not really looking for anything romantic right now …” or as is more often the case, no message at all.

Donation clinics seem to follow a similar story line to entice potential donors: Help a woman achieve her dream of parenthood. Do your part; be there when needed. You’re worthy, and wanted, though of course you’ll remain nameless. It’s not a huge time commitment, and the rewards of your selfless act are great.

The language of those who believe in or practice or have had children by egg donation is equally affirming, welcoming for a young woman who may want to feel needed — more along these lines, taken from parents via egg donation dot org:

At the end of the day, we believe that the child you have via this process is the child you are meant to have, and will be the most amazing, beautiful, perfect child you have ever laid on eyes on.

Engaging in egg donation is a sensitive matter, not least for expectant couples. Based on comments I’ve read while trawling fertility blogs, the main rhetorical defense for women who conceive by donation is that they choose egg donation out of desperation, not a desire to play at being Creator. This was a last-ditch option after a long period of suffering from infertility and/or miscarriages, the donor-parent bloggers explain. One or two will make a concession to adoption: “it’s a very personal choice, and my partner and I did not want to embark on that process.”

They all insist that egg donation is not a “creepy” attempt to “create the ideal child.”

They make the point, about being selective, that this is little different from the lack of “equal opportunity” that goes into, if one is heterosexual, selecting a man to procreate with according to his physical, intellectual, and emotional characteristics.

I feel for these women. It is awful, I am sure, to be told you cannot have children through your own womb when that is all you desire. And while the selection of traits is not “creepy,” nor morally wrong, it differs significantly from dating. Money, primarily, but also anonymity, are directly involved in this selection process.

“I see no reason,” an egg donor proponent insists, “why there should be limits on what is important to egg donor recipients or how selective they want to be. Most of us come to realize that being too selective has its trade-offs -- it becomes more difficult and sometimes more expensive to find a donor.”

Yes, is hard to have choice, and oftentimes burdensome to be rich and selective. Though I do have my doubts about these ethical questions, I’m less concerned with morally judging those who engage in donation on the side of becoming parents. It’s probably true for thousands of couples that dream of pregnancy and resort to egg donation that the ability to have a child at all is a “wonderful gift.” But the aggressive sentiments expressed in certain comments on egg donor forums are of concern. The women and men (or compensated spokespersons) who feel it necessary to affirm that “no one is being paid for eggs,” or that they’re “tired of journalists trotting out extreme cases to make a point,” or that “concern over egg donation is indeed excessive … it seems unlikely that anyone will ever be exploited, certainly not the donor …” are actively denying the fact that these gifts, donated or otherwise, are often wrapped in the exploitation of an invisible other.

It may be a miracle to live in an age where if you cannot have a child — which is itself its own, very real trauma — you can trade your money and perhaps some of your own medical risk to purchase and implant some other, poorer woman’s eggs. Yes, she may be drawn into risky behavior solely because she can gain thousands of dollars that can ease her current desperation, but if she goes into it willingly, is it right? Furthermore: as a practice, is it predatory?

First, let’s step outside of the prescribed language and call it what it is. Egg “donation” is not donation. “Donation” is giving something of yourself to another without compensation. Despite the careful legal language and the focus of fertility clinic rhetoric on altruism (there’s a place called AltruiDonor in the UK), “egg donation” amounts to the selling of one’s eggs. An $8,000 price tag is enough to cloud the judgment of many a well-educated woman.

It certainly clouded mine. I could use the money. I could assess the risks as abstractions: Who is to say that I would rage uncontrollably at the excessive doses of hormones? Would it be so bad? Would cancer be so bad? What seemed less abstract was my need to eat, have shelter, and the luxury of time to live rather than simply work, work, work.

What I saw, given the option to sell, was not risk, nor even a reflection of my own self. What I saw was a warped Maslow’s pyramid with a neon green dollar sign flashing out front.

Being a woman under late capitalism is confusing to begin with. The glass ceiling still exists. It is smeared in glittery pink paint, with the phrases “for her” and “goddess” scribbled in curly font, and in some places scrubbed so clean with streak-free Windex, denial, and a false sense of equality that often, a woman crashes uterus-first into it under the auspices of undeterred ascent. This past year, a few tokens of success were won and doled: Some women in the U.S. can legally marry their female partners for the first time, China saw its first female astronaut, Saudi Arabia its first female athlete.

But we still, incredibly, receive less pay for equal work. 2012 saw the passing of anti-choice legislation, one of the more egregious internationally-reported cases of gang rape of a woman, a teenage girl blamed by a high school football coach for her own well-documented sexual assault on national news, and a court determining it was acceptable for a woman to be fired based upon her “irresistibility.” Sexually promiscuous women are still called sluts and whores by their peers but boys will always be boys. I’ve seen it when I’ve been or felt sexually harassed, looked down upon, paid less, ignored while asking for compensation, and asked -- or, rather, told -- to do extra work without being compensated more. It’s been assumed that I would be thrilled to “help out.”

How does the prospect of selling eggs fit into this perplexing time to sport a vagina? Egg donation, as an option, can be seen at once demeaning and empowering: A job that no one else but a woman can have — or rather, a racially pre-selected, usually white, struggling, middle-class, educated woman — can have. For the infertile, the homosexual, the single, and the well-to-do, egg donation is another of the joyous luxuries of modern science. But then there are the women who act as that market’s laborers and nameless vessels; those who are themselves farmed -- the anonymous sows, cows, or bitches pumped with hormones and praised for their pedigree and exaggerated numbers of follicles.

For me, the prospect of donation felt very much like a prospective job. I crouched into a corner at the college where I tutor and did my best to sound bright, willing, and compassionate on my phone interview. I made sure to compose myself, to mention where I was and why I was unable to talk just then. I was busy. I was volunteering in the Rockaways after Hurricane Sandy. I was willing to go where I was needed, ready to risk something — anything maybe, to lend a hand or, by extension, an egg.

A series of phone calls in the weeks following New Years tested my understanding of what it means to find, land, and perhaps most challengingly, say no to a job as a woman. The clinic called as I was exiting a screening of the Cain and Abel parable "East of Eden." I scrambled to find a seat on the steps in MoMA while listening to a counselor from the clinic ask whether my eggs were still available for hire. My genetic material, in the eyes of the scientists and doctors, had been certified, approved.

As I dug for a pen in my bag, I hesitantly confirmed my interest in having my eggs primed and pumped and harvested, but requested a phone number to call in case anything was to come up in the next week.

By this point, something was already not sitting well with me, but how could I say no? I wanted to feel in my own organs and mind what it’s like to be a harvesting site, understand the sensation of a specialized end of the biomedical complex opening up my vagina for the hands and bodies of someone richer than me. I wanted the money. And, oddly enough, I still was convinced by the narrative. I wanted to be wanted. I wanted to help.

I later spoke with my most trusted confidant about the donation. This is a wonderful and supportive person; one who’s never come close to telling me what to do nor mansplained or spoken at me rather than with me. But as I continued to seriously consider taking $8,000 for my “inconvenience,” he did something he doesn’t ever do: He talked at me.

And I did something that I don’t always do: I listened. He told me he’s deadly wary of the mental and physical ramifications of a procedure that favors the buyable, limited-accountability, bourgeois capital-E Experience of parenthood for the rich at the cyborgian risk of egg and life of the poor.

There are plenty of children without homes already. Why should a woman need to experience pregnancy if she cannot for any number of reasons? Logically this makes sense, that I should not want to participate in a cycle that harms me for an ultimately unnecessary, highly individualistic system that literally harvests desirable body parts from the poor in order to satisfy a perceived need — a desire, a lifestyle fantasy of the rich.

Then again, taken to extremes, these arguments are privileged, moralistic, religious, anti-choice, even anti-woman. If a woman who cannot conceive, or a couple who both possess the same anatomy want to grow a child and have worked hard to Afford the Experience, the market, the law, and some part of me believes they should be able to do so.

But something deep in my proud fallopian tubes tells me that I don’t have to be the one to provide them with the live materials to fulfill this dream. I have the critical capacity to extract myself from the narrative the clinic attempted to sell me on. I want but, thanks be, don’t need the money. I will live. I will keep working my four-to-five jobs, and will find another that treats me with respect for my time and needs. I’ll participate in the system, and abide by the sickening calculus, in turns taking advantage and being taken advantage of.

But there’s no need to place my own two ovaries at the center of an extreme capitalist experiment. Thankfully the rest of my body and my mind still work, and I do not need to risk the dissolution of those two organs to rent out my uterus at a premium just yet. I don’t want my story to be incomplete, but I don’t want it to end so explicitly as: “I bought a year in this apartment, started this savings account, purchased extra time by participating in something that harms me in order to benefit someone else.” Or worse, “I traded a few months’ financial security for this cancer, this mental fatigue, this overstimulation of my ovaries.” I am already doing enough free labor by stroking the face of my iPhone for likes or placing my hours in the service of worthy but non-financially-supporting causes. In this economy, I can’t risk further self-exploitation.

I called the fertility clinic, shaking, ready to turn down the offer. Had I ever done this before? Not really. I’d been edged out of jobs for unknown reasons — too uppity, too proud, too much of a flirt?

No one picked up; I left a message. I practiced what to say. I would tell them, firmly but as politely as possible, that I did not want the job.

In the end, I blamed time. “I’m actually going to be working quite full time, and likely traveling, so thank you for considering me, but now’s just not the right time,” I said.

I hung up and felt proud of my liberated ovaries. I knew I would be working “quite full time,” but the day after the phone call work picked up more than usual. I was busy holding interviews for well-qualified interns willing to work under me for free, and I didn’t interrupt a hopeful to take a call from an unknown number.

I stole a moment to listen to the message: “Hi, this is so-and-so from the clinic. Thank you so much for calling. I just wanted to have a conversation with you …” She proceeded to inform me that donation would not actually be a big-time commitment. There would be a single, two-hour teaching class, where I’d have an opportunity to ask questions of a doctor and, from the tone of her message, where I was likely to feel pushed up against a wall.

“All of the injections would be before work hours,” she cooed, “and then you’d pretty much be done. The woman who’d be your match is really looking forward to going through with this …”

Shouldn’t a clinic that works specifically with women and their reproductive systems know better than almost anyone that no means no? I felt ill; an invisible rubber-gloved hand was groping my liberated lady parts.

I am sure the counselors at the clinic, like any good salespeople, have a script to follow when a woman no longer wants to participate in donation but retains a hint of politeness — hesitation — in her voice. A speculum I can take, but coercion I will not stand for. Who was this woman whose narrative was being used to ensnare my supposedly altruistic follicles? I wonder, and still don’t know, how hard it was for her and for the clinic to find a “match.”

But having read the anonymous experience of at least one former egg donation clinic employee, I understand I was the ideal candidate. Had I told them I was homosexual, had I been nonwhite, or less educated, I would have been rejected; I would not have been praised or preyed on. I could have been firmer to begin with, but how like a woman to chastise her earlier actions for the way she feels taken advantage of later. I’d made my decision; I didn’t owe them time. The danger, and also the benefit, of anonymity is that accountability has its limits.

I didn’t call back. I was busy working three or four of my five jobs at once, and hearing bright young women tell me why they wanted to work for me for free.

I cannot languish in abstractions forever. Much of what I do, what we collectively in the global north do, is either harmful to our own bodies, the bodies of Others, or the world in which we live. I am writing from a place of tremendous and precarious privilege, one where I get to make almost all of the decisions about my own body. But there is no need to push this reality to physical extremes, to put my organs in the service of someone even higher above me in the great pyramid scheme. Unlike in most things, I do have the clear-cut choice to refuse to participate this time. I can take my pre-approved genetic material — thank you so much for the opportunity! — and run.

Shares