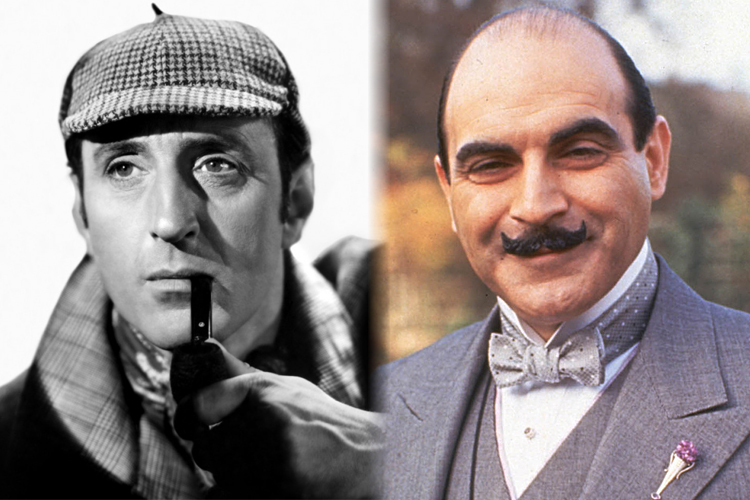

Sherlock Holmes was a virgin. Hercule Poirot was a prude. And, I don’t know Miss Marple all that well, but she was hardly Aphrodite. One thing is for sure: The great private detectives of the English whodunit weren’t doing it.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Victorian-era superman, with his Freudian appetite for cocaine, did not otherwise abstain according to his epoch’s mores, but lust was as foreign to Holmes as frivolity. His acute powers of deduction left him cold and indifferent to the powers of seduction. “He” famously “never spoke of the softer passions, save with a gibe and a sneer,” wrote his dutifully Boswellian Watson. “They were admirable things for the observer — excellent for drawing the veil from men’s motives and actions. But for the trained reasoner to admit such intrusions into his own delicate and finely adjusted temperament was to introduce a distracting factor which might throw a doubt upon all his mental results.” This a-romantic remove set him apart, both from the corruptible creatures he studied as if through a microscope, and from the community of literary characters at large. Aside from perhaps Tom Jones, Holmes was our first and — along with Poirot’s contemporaries in the pages of Virginia Woolf and E.M. Forester — our most significant asexual character in fiction.

It is a tricky thing, making of an abstemious protagonist a vivid personality. It is usually in the so-called base passions, the Tolstoyian temperaments, that a character reveals himself. So it is rather a unique accomplishment that Doyle’s and Agatha Christie’s famously rigid, um, dicks read as anything but robotic. (It is interesting to note that neither Christie nor Doyle was particularly celibate or anhedonic, as far as we can tell: She wrote out-and-out romance novels under a pen name, and they each married more than once and had children.)

But in a procedural, a hound with scent only for the case is of course a compelling plot engine. There are no softer passions to distract, no veil to be drawn on their motives. Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett’s noir creations hardly ever sleep and, confusingly, never seem to take the money they work for. But Holmes and Poirot never even fall for the femme fatale, never get duped by the dame.

In fact, both were so titanically vain we could suspect some disorders in the direction of self-love. But even as they performed their lives, reveling a little too much in their recognition, they faced down the creeping evil in their creators’ cosmos to which they were ideally suited. Holmes’ outsize ambition fit squarely with Doyle’s Great-Man-Theory approach to narrative, with its supervillains and sullied heads of state, but never placed him in any danger of corruption. He was almost allergic to flattery and outright disdainful of his social superiors and the positions they held, or could offer. Poirot’s England was rotten, like all of Christie’s work, with greed — every other second sister, it seems, was poisoning her whole family for a pitiful inheritance — a vice unknown, somehow, to the Belgian dandy who policed it. For Poirot, his tisane, chocolates and a crème de menthe were preferable to dinner with the king, though he would rather have enjoyed a knighthood, I suppose.

Considering their many similarities — the vanity, arrogance, their hometown, trade and incredible brains — they could hardly be more dissimilar. Holmes was debauched. Poirot was a connoisseur. They are entirely different expressions of Kierkegaard’s tussle, in “Either/Or,” between the aestheticist and the ethicist. Poirot is a retiring hedonist who occasionally takes a case for the honor, out of sympathy or to right a wrong. Everything in Holmes’ life has value in so much as it provides challenge and entertainment in the form of puzzles. He needs the world to become a game in order to escape the excruciating torrent of his idle mind. Poirot would rather everyone get out of his way so he can properly enjoy those chocolates.

Above all, Holmes and Poirot were immune to the allure of sex — so powerfully repelled, in fact, that in their company we are made to view carnality as a weakness, even a sickness, leading only to blackmail, syphilis and adoptions. “[Holmes] had a remarkable gentleness and courtesy in his dealings with women,” writes Watson, who looked on his companion’s misogyny and violin playing with equal bemusement. “He disliked and distrusted the sex, but he was always a chivalrous opponent.” This dislike and distrust has led, over the years, to speculation that Holmes favored other players, perhaps even ol’ Watson if we are to take recent spirals of fan fiction, or Guy Ritchie’s pinhole adaptations, at all seriously.

Poirot, on the other hand, would have provided a diagnostic field day for a psychoanalyst. His obsessive compulsive disorder — color-coding his socks, aligning his desk mathematically — is legend; his anal-retentiveness, the butt of many jokes (sorry, but seriously). David Suchet, who has played Poirot for 24 years, and filmed nearly every one of Christie’s stories about the detective, has said that he achieved his distinctive walk by clenching tight his buttocks, an expression of Poirot’s extreme condition. And he has dismissed assumptions that his character, or his source material, is homosexual. “Some people think he’s gay, but no!” Suchet said. “No, Poirot is definitely not gay. He fascinates me because he has a very particular sexuality. He’s not actually sexual at all, is he?” Not if we use Gore Vidal’s criteria — that there are neither hetero- nor homosexual people, just hetero- and homosexual acts — he’s not. Neither Poirot nor Holmes have acted in any way, you know, that way, whatsoever.

Which, as you’d suspect, leads to rather odd fixations, of which both men have several. Obsession is a mood for them and they pass their lives moving from one to another. But none so frequently or as thoroughly as the one who got away. For Poirot it was the Countess Vera Rossakoff. “It is the misfortune of small, precise men always to hanker after large and flamboyant women,” apparently. “Poirot had never been able to rid himself of the fatal fascination that the Countess held for him.” Fatal in the sense of occasional. Though she did trigger his sometimes wavering morality (like letting a trainload of murderers get away scot free on the Orient Express, for example), and escaped persecution with his protection.

Like Rossakoff, Holmes’ fixation was also a jewel thief. But whereas the “Countess” was an affected emblem of glamour, Irene Adler was a bawdy cross-dresser, though no less captivating. “To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman,” Watson noted. “I have seldom heard him mention her under any other name. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex.” Though, we are not to misunderstand the situation. “It was not that he felt any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler. All emotions, and that one particularly, were abhorrent to his cold, precise but admirably balanced mind … And yet there was but one woman to him, and that woman was the late Irene Adler, of dubious and questionable memory.”

Of dubious memory, to be sure, but, as we know from fables and Hollywood, love conquers all. So, why, then, did Sherlock not pursue his love as doggedly as he did Moriarty, nor Poirot his elegant muse? Well, because these men were not just early templates of the saintly celibate, sacrificing their mundane desires for a higher good. They were asexual — more, a-romantic, which is to say, people who have neither sexual nor romantic feelings. The distinction is important.

There are those, of course, who lack sexual desire (though may still sleep with people, out of curiosity, or some sort of normative impulse, like Liz Lemon), but fall in love. There are those who want to have sex, but abstain, for reasons of age, illness, aesthetics or hygiene. There are even those who think of sex the way oldtimey football coach Woody Hayes thought of the forward pass — that only three things can happen when you do it and two of them are bad.

In the past couple of years the asexual community has found de facto spokespeople in style guru Tim Gunn and stand-up Janeane Garofalo (maybe?), and acquired an identifying logo (a shaded triangle) and a pride flag. In America and England, at least, Kinsey’s famous “X” designation has recently seen an increase in awareness, if not in identifying population (most experts believe a constant 1 percent of people are asexual). So, while we await some future “Girls” episode to bring about a broader understanding of asexuality identity, we can always turn to our much-beloved Golden Age detectives as referents. Their secret lives and little gray cells are so deeply ingrained in our consciousness as to be mythological. And, while they are unique and not-always-lovable snowflakes, they provide specific and well-understood behavioral modes with which to compare and contrast identifiers within a broader sexual orientation.

It’s elementary.