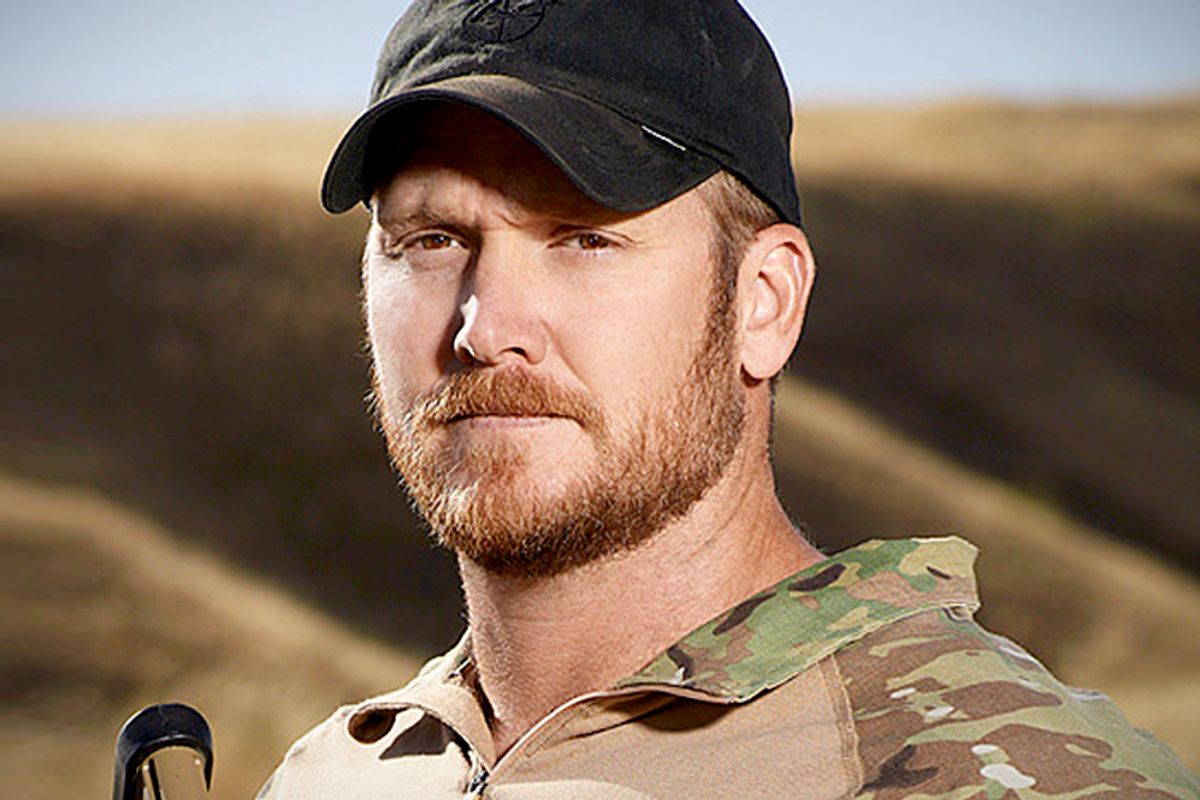

"I am not a fan of politics," wrote Chris Kyle, the 38-year-old former Navy SEAL sniper who was shot and killed with a friend at a Texas firing range on Saturday. Yet, in his best-selling memoir, "American Sniper: The Autobiography of the Most Lethal Sniper in U.S. Military History" -- originally published last year and currently experiencing a sales bump in the aftermath of Kyle's death -- the commando also wrote, "I like war." The problem, as Kyle would have known if he'd read his Carl von Clausewitz, is that the two aren't separable; war, as Clauswitz wrote, is the continuation of politics by other means.

Chances are, though, that Kyle never heard of Clausewitz; certainly there's nothing in "American Sniper" to suggest that he ever thought very deeply about his service, or wanted to. The red-blooded superficiality of his memoir is surely the quality that made it appealing to so many readers. Well, that and Kyle's proficiency at his chosen specialty: He boasted of having killed over 250 people during his four deployments as a sniper in Iraq. While Kyle’s physical courage and fidelity to his fellow servicemen were unquestionable, his steadfast imperviousness to any nuance, subtlety or ambiguity, and his lack of imagination and curiosity, seem particularly notable in light of the circumstances of his death. They were also all-too-emblematic of the blustering, tragically misguided self-confidence of the George W. Bush years.

A self-described "regular redneck," Kyle grew up in Odessa, Texas, and spent his youth hunting, collecting guns and competing in rodeos until he found his life's purpose in the Navy SEALs. "American Sniper" lovingly recounts both the rigors of the special-operations force's training program and the extravagant hazing to which new members are subjected. (Kyle was handcuffed to a chair, loaded up with Jack Daniel's, stripped and covered with spray paint and obscene marking-pen tattoos by his buddies on the night before his wedding. Presumably his bride got the message about whom he really belonged to.)

When the action-hungry commando finally got to Iraq during the initial push of the war in 2003, he was confronted for the first time with the soldier's prime directive: to kill the enemy. In Nasaria, Kyle shot his first Iraqi (an incident that opens the book), a woman he spotted on a road pulling a grenade from her clothing to throw at an advancing Marine foot patrol. "I don't regret it," he writes. "The woman was already dead. I was just making sure she didn't take any Marines with her."

It is both cruel and perverse to reproach soldiers for killing the enemy when that's what they're sent to war to do, and when they do so in defense of their own lives and the lives of their comrades. Nevertheless, you can expect soldiers to kill and still recoil when they kill blithely and eagerly. In "American Sniper," Kyle describes killing as "fun" and something he "loved" to do. This pleasure was no doubt facilitated by his utter conviction that every person he shot was a "bad guy." Fallujah and Ramadi, where he saw the most action, were certainly crawling with insurgents and foreign Islamist militants, and Kyle swears that every man he picked off with his sniper rifle was manifestly up to no good. But his bloodthirstiness and general indifference to the Iraqis and their country don't suggest that he was highly motivated to make sure.

"I don't shoot people with Korans," Kyle retorted to an Army investigator when he was accused of killing an Iraqi civilian. "I'd like to, but I don't." Later in "American Sniper," he announces, "I couldn't give a flying fuck about the Iraqis." "I hate the damn savages," he explains. What does matter most to him are "God, country and family" (although much of the friction in his marriage arose from his ordering of those last two items). As Kyle saw it, he and his fellow troops had been sent to war in this contemptible place "to make sure that bullshit didn't make its way back to our shores."

In Kyle's version of the Iraq War, the parties consisted of Americans, who are good by virtue of being American, and fanatic Muslims whose "savage, despicable evil" led them to want to kill Americans simply because they are Christians. (Later in his service, Kyle had a blood-red "crusader cross" tattooed on his arm.) While he describes patriotism as the guiding force in his life, Kyle's patriotism is of the visceral, Toby Keith variety. It consists of loving America -- specifically, being overwhelmed emotionally by the National Anthem and flag, and filled with a desire to dedicate one's life to such symbols -- rather than a commitment to tangible democratic principles, such as civilian oversight of the military. That Iraqis, too, might have been patriotically motivated to defend their own country against foreign invaders like himself does not appear to have ever crossed Kyle's mind.

As for Americans, they come in two varieties: "badasses," of which Navy SEALs are the premiere example, and "pussies." The latter could be anyone from congressmen who impose onerous restrictions on, say, a SEAL sniper's freedom to shoot anyone he deems a "bad guy," to journalists who present unflattering reports on military activities. The recurring designation of "bad guy" suggests just how profoundly Kyle's view of the conflict was shaped by comic books and video games, where moral inquiry takes a back seat to heroics, exhibitions of skill, gear and scoring. (In Ramadi, Kyle and another sniper, egged on by their superiors, hotly competed to be the one to officially kill the most people.)

In the world of the video game, there's no difference between a reason to kill people and a pretext for doing so; the point of the game is to kill, and the reason (they're "bad guys") is just an excuse. In real life, the reason is everything (unless, that is, the killer is a psychopath). A soldier almost always has an excellent reason: protecting himself and his comrades. But when soldiers are part of an invading army, the more thoughtful among them usually end up asking why they and their buddies have been put in mortal danger to begin with. That's why so many Iraq War memoirs resolve in bitterness and betrayal. The heroism and sacrifice of the troops were very real, but the war itself was based on lies.

All such questions about the origin of wars amount to "politics," and they're a bummer if what you really want is to read about exciting house-to-house battles, amazing long shots made with lovingly described high-end weapons and anecdotes celebrating the strutting prowess of elite American commandos. To get that sort of book, you need that oxymoronic thing, an unthoughtful writer. "American Sniper," which was produced with two ghostwriters, is a work that would never have existed were it not for Kyle's own glamorous, mediagenic reputation because he sure wasn't going to produce it on his own; you get the impression that he exerted enormous efforts not to reflect on what happened in Iraq and why. You'll find no mention of Abu Ghraib, the WMD fraud or the pre-war absence of al-Qaida operatives in these pages.

Kyle's account of his return home suggests that it was not just the rationale for the invasion that messed with his simplified, sentimentally patriotic conception of the Iraq War. He went from one drunken brawl to another, including an alleged altercation with Jesse Ventura. Kyle's description of that led to a libel suit: Ventura says the fight never happened. The former Minnesota governor has always forthrightly expressed his opposition to the Iraq War, but Kyle claimed that Ventura had insulted American troops. To judge by other passages in "American Sniper," Kyle doesn't seem to have understood the difference, or to have considered the possibility that opponents of the war also wanted to save American lives. War and politics: difficult to separate even when you're hellbent on denying the connection.

Kyle finally sobered up. (It was totaling his pickup that did it, but he also missed one of his kids' birthday parties because was in jail for a bar fight.) By all accounts, he had begun to wrestle with the war's toxic legacy, establishing a nonprofit that donated in-home fitness equipment to veterans suffering from the physical and psychological toll of battle. Kyle's dedication to his fellow fighters was admirable and selfless, and exercise can be great therapy. Still, the preference for activity over rumination and consideration remained a persistent theme.

Eddie Routh, the veteran who shot Kyle and his friend Chris Littlefield, had reportedly been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of his experiences in the war. In the immediate aftermath of Kyle and Littlefield's murders, many people expressed incredulity at the notion of taking a person troubled with PTSD to a firing range. One-time presidential candidate Ron Paul provoked a firestorm of criticism by questioning this choice and tweeting, "he who lives by the sword dies by the sword." (Word of advice: Twitter, like video games, is not an appropriate forum for complex argument.) In fact, controlled exposure to triggering stimuli is an established treatment for PTSD. It works much like phobia therapies that have patients, under a therapist's guidance, first imagine and then gradually encounter the objects of their fears. Over time, the triggers can be desensitized.

But Routh also appears to have had other underlying mental health and substance abuse issues. He'd been hospitalized multiple times for threatening to kill both himself and family members. He may have had problems that pre-existed his service or that were exacerbated by it. Furthermore, there's no indication that Routh was receiving any kind of psychotherapy or that Kyle and Littlefield had run the firing range idea past a therapist who was familiar with his case. Why should they? What would some egghead, like the brass and the politicians, who had never been in the shit, know about it, anyway, compared to someone like Kyle who had actually been there? Routh was not just an American, but an American soldier, a person who was by definition incapable of doing anything evil.

Shares