This year’s foreign-language Oscar race may seem like a foregone conclusion, with all the entirely justifiable attention being paid to Michael Haneke’s extraordinary “Amour.” Don’t let that deter you from seeing “Lore,” a strange and intimate childhood odyssey set in the immediate aftermath of World War II, which is every bit as remarkable in its own way. The title, by the way, refers to the teenage German protagonist’s nickname (short for Hannelore) not to the English word indicating tales and knowledge, although you’re free to construct a double meaning for it if you care to.

For academy purposes “Lore” is classified as an Australian film, and it certainly propels previously obscure Aussie director Cate Shortland onto the global-cinema map, but it was made entirely in Germany, and the only fragments of English you’ll hear come from American soldiers. You may be thinking you don’t have the emotional and psychological space for yet another movie about childhood in wartime or the legacy of the Holocaust, but I promise you that “Lore” offers a vision of the costs of war at an individual level, along with a challenging moral parable, that’s not like anything you’ve seen before. In its ruthless detail and its unsentimental violence, “Lore” is certainly reminiscent of Roman Polanski’s “The Pianist,” and the story it tells is just as chilling in a different direction.

As I left the screening of “Lore,” I heard another New York critic grumbling about how he didn’t much care what happened to the children of the Nazis, and I guess that’s a valid response as far as it goes. Certainly Shortland and co-writer Robin Mukherjee (adapting a novel by Rachel Seiffert) ask us to face that question: Amid the chaos and suffering of the collapsing Third Reich and the shocking revelations of the death camps, does our sympathy extend to four children whose parents were enthusiastic supporters of a genocidal regime, and may well have been war criminals themselves?

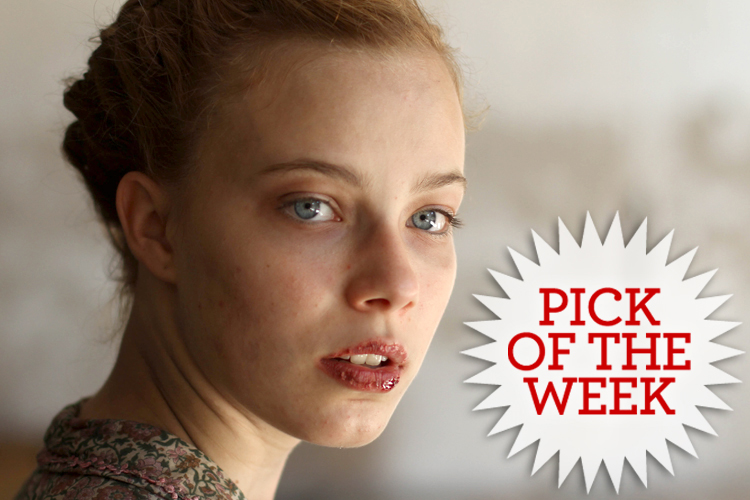

Staying close to the perspective of Lore (Saskia Rosendahl), a lovely girl of 14 or so, the film offers little background or context. We have to put together the pieces ourselves from a disordered early narrative Lore doesn’t quite grasp: Her “Vati,” or daddy (Hans-Jochen Wagner), wears an SS officer’s uniform, and her stylish, ice-blond “Mutti” (Ursina Lardi) is furious that she has to load up all her silver and jewelry and abandon their luxurious villa for a remote cabin in the Black Forest. (Where the silver and jewelry came from, and whom the villa once belonged to, are questions we may wonder about.) The “Final Victory” promised by their beloved Führer is still coming, Mutti assures Lore sardonically, but apparently not just now. We never learn Lore’s parents’ names, but it doesn’t much matter. They’re gone from the story soon enough, although Shortland does compel us to face the unpleasant fact that thousands of German women were raped by conquering Allied soldiers as the war wound down.

With her parents gone, Hitler dead, and Allied martial law in place, their rural neighbors want nothing more to do with the Nazi officer’s five kids (one of them still a baby). Lore is forced to lead her siblings on an unforgiving trek clear across Germany from south to north, in hopes of reaching their grandmother’s house outside Hamburg. It’s a remarkable visual, cinematic and moral journey, but exactly the same qualities that lend “Lore” its unusual power will also make it a confusing and frustrating experience for some viewers. Cinematographer Adam Arkapaw’s camera (he also shot “Animal Kingdom” and “The Snowtown Murders”) stays close to Lore’s face, Lore’s point of view and Lore’s limited comprehension of events. We get few geographical clues about where we are, and only fragmentary encounters with other people, living and dead. We only glimpse the posters of death-camp atrocities that the Allies put up in many German towns, and can only guess what Lore thinks about them.

We do know what Lore thinks about Thomas (Kai Malina), a brooding young man with close-cropped hair who has begun following them. Or rather, we know that she doesn’t know what to think, or has competing and conflicting thoughts. He has a number tattooed on his arm, and an identity card with a yellow Star of David, and she has been taught her whole life that those people are dirty and untrustworthy, the enemies of Germany. On the other hand, she’s also aware of the harsh, hungry personal chemistry between them; on a sunny afternoon, in a bombed-out building in the middle of nowhere, she walks over to him and puts his hand on her leg, under her skirt.

But there is no easy symbolic reconciliation between Jew and German available in “Lore,” any more than there was in the real world. It is just possible that Lore’s ambiguous interactions with Thomas awaken her to their shared humanity, and to the first stirrings of a moral response to the crimes committed by her parents and their entire nation. But in the short term, they’re both trying to survive, and they’re both willing to do cruel, immoral and even unforgivable things in order to do it. Thomas remains an elusive character whose life story we never learn, and Lore keeps encountering gentle older people who treasure quasi-religious wall portraits of Hitler, and who assure her in shaky voices that the Allies’ supposed death camps are scurrilous fictions.

“Lore” has been described as an accidental sequel or companion piece to Haneke’s 2009 “The White Ribbon,” an ominous black-and-white mystery that sought to identify the roots of Nazism in the rural Germany of the early 20th century. That’s probably too neat an equation, but there’s something to it: If Haneke showed us a generation that incubated a lethal virus, so to speak, Shortland shows us a generation that was forced to face its consequences, and at least partly succeeded in stamping it out. Whatever you might want to say about contemporary Germany, which will no doubt be haunted by the memory of the Third Reich for many generations to come, it shows no signs of devolving into insanity and barbarism.

If “Lore” is an upsetting and uncomfortable film set in a morally bleak landscape, it also offers a guardedly optimistic vision of the possibility of human change. Maybe the true companion piece to this film is less “The White Ribbon” than Israeli director Chanoch Zeevi’s bittersweet documentary “Hitler’s Children,” which explores the lives of contemporary descendants of Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler and other Nazi leaders. Should we care about the children of Nazis and Klansmen and KGB torturers and Hutu warlords? Well, we’re all imperfect beings, and no doubt it’s understandable to care somewhat more about the children of their victims. But in the long-term moral calculus, we have no choice.

“Lore” is now playing in New York and Los Angeles. It opens Feb. 15 in Chicago; March 1 in Boston, Portland, Ore., San Francisco, Seattle and Washington; March 8 in Atlanta, Denver, Philadelphia and Waterville, Maine; and March 15 in Charlotte, N.C., Knoxville, Tenn., and St. Louis, with more cities and home video to follow.