Mostly, when I write music criticism, I write about things I like. I write about things I like not because I am apprehensive about the reaction when I dislike something, but because I approve of what happens with language when I feel strongly. Praise makes for good prose. Recently, though, I thought I might test the waters and write about something I disliked a good deal. My hypothesis was simple: Maybe, occasionally, a violent distaste can make for interesting prose, too.

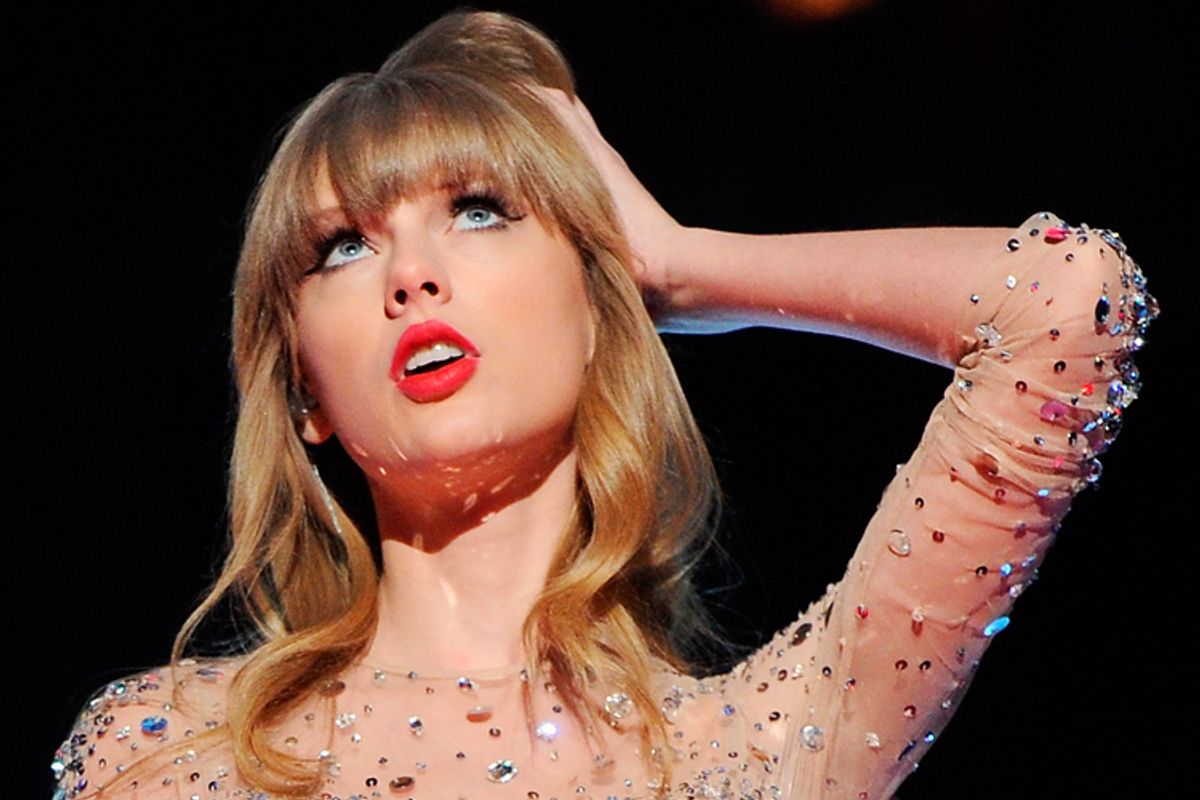

The music I chose was the music of Taylor Swift. So I wrote about disliking the music of Taylor Swift over at the Rumpus, where I have been writing music criticism since 2009. In this case, it should be said, the majority of my column (a miscellany of brief thoughts I have had about various musical phenomena since last summer) was the usual hortatory stuff: shout-outs about a Los Lobos show I saw last summer; about the new Young Fresh Fellows album (great! buy it!); about the breakup of the band called the Books; a brief attempt to connect Owen Ashworth (of Casiotone for the Painfully Alone) to Raymond Carver and so on.

And then there was the section about Taylor Swift, which amounted to 750 words in a 5,000-word piece.

I will admit that in attempting to describe the bludgeoning I feel when I experience a Taylor Swift song, I did engage in some rhetorical flourishes that feel rhetorically showoffy: “These songs actually do sound to me like what the undead would sing if they were capable of singing,” or: “Taylor Swift makes music about as interesting as Olestra-based products, or Swiffers in multiple colors, or tiered Jell-O dessert products, or milk from China that has lead in it, or home cosmetic surgery or rectal bleaching.”

These sentences do constitute a provocation, but, even now, I don’t shrink from the sense of them. I still dislike this music passionately. For example, I am really irritated by the way in pronouncing “ever” in her complains-too-much newish single “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together,” she sounds remarkably like Blink-182.

Still, I was not prepared for the assault that lay in wait for me when I published this piece, and on this basis (lack of preparation for the assault), we can only say that I am hopelessly naive. I suppose my thinking was that The Rumpus, where I publish this work, is pretty intellectual and bookish -- and when it is more than intellectual, it is usually engaged with matters of sex and politics, and so its audience is literary and pretty progressive, and they are not going to mind a little carping about Taylor Swift. Apparently, I either underestimated the diversity of The Rumpus' audience or I was hopelessly unaware how many Swiftians use Google Alerts to keep up on matters pertaining to their muse. Because although there was a day or two when people commented about Los Lobos, things on the comments page pretty quickly turned into a trench war about me and Taylor Swift.

The locus of fury seems to have been this passage:

When [in the future] we are forced to listen to two or three more of these albums, we will, as people do with relentlessness generally, begin to form a hard impenetrable exoskeleton to the work of Taylor Swift, and we will begin to hate it, and we will say horrible things about it and about her. This will not matter, because her parents work in finance, and she has good manners, and she’s going to marry up, and she’s going to get into the movies (not just guest appearances in "CSI"), and she’s going to launch some clothing lines at Target (no, wait, I think she already did that), and a personal fragrance (I think she did that too), and parlay all her bad press into some self-serious complaints, making good on every opportunity to monetize her career at the expense of making actual art.

The response to this paragraph has been startlingly vituperative. Not as bad as the reaction to that recent Michael Jackson biography, but pretty bad. First, it is alleged that I am a misogynist for the “marrying up” line, with the particular charge being that I wouldn’t say this about a male artist. I would, however, say this about a male artist, so let me correct that misperception now: Larry Fortensky married up, David Gest married up, Tim McGraw married up. And even the president of the United States has admitted to “marrying up,” I believe, in referring to himself. There has also recently been a Redbook article on the subject of “marrying up.” In fact, there’s even a sociological term for this, hypergamy, and the interesting thing about hypergamy, according to one study, is that it’s evenly distributed between the sexes.

Second, I am accused of being a misogynist for pointing out that Swift is a careerist, as in the following post from the comments board: “Criticizing a young woman’s work as ‘repellent and artificial,’ as ‘stealing,’ as ‘manufactured, ungenuine,’ not to mention all the class bullshit, the ‘making good on every opportunity to monetize her career at the expense of making actual art,’ is such typical misogynistic drivel.”

But it should go without saying that there are any number of male artists who are just as careerist (except, perhaps, that they don’t often have fragrances). Just as artificial, just as manufactured, and with just the same relentlessness. The obvious example, at the moment, would be the equally hard-to-listen-to Justin Bieber, and his mother’s politics (and his parroting of same) would seem to be part of the horror. Yes, these male artists, whose approach to career building is more about branding and market share, are just as repellent and artificial to me as Swift. One day, perhaps, I will write about the structural similarities between the careers of P. Diddy and Taylor Swift.

I dislike the Bieb passionately, I also dislike One Direction, I can’t bear any of that new “country” music — those flag-waving meatheads like Toby Keith — and I reserve a special place in my cavalcade of contempt for, for example, Kid Rock, the musical equivalent of a bottom-feeding heterodontus, who mixes together the basest impulses of “country” and “hip-hop” and auto-tunes himself on the occasional ballad because the chances of tunefulness are presumably dim. I make the foregoing catalogue to indicate that in order for “misogyny” to stick as a criticism of me, a pattern of “hatred of women” would have to obtain. And no such pattern exists, because The Rumpus column itself included three sections about women artists: about Marcia Bassett (a very unusual electric guitarist of great promise and innovation), about the Brooklyn band Universal Thump (which has a female singer who is also a very talented arranger) and also about Jolie Holland and her remarkable and astonishing recent cover of Townes Van Zandt’s “Rex’s Blues.” It’s Jolie Holland, if you ask me, who should be performing on the Grammys this week, not Taylor Swift. Only then there would be justice in the world.

Nevertheless, I am a misogynist according to the Swiftians, and I should die. And elsewhere, on the broad avenue of the Internet, it is alleged that I am “too wealthy” to criticize Taylor Swift, or too “old,” and that the music “is not for” me. (By the way, if I am “wealthy” then Taylor Swift is Sheldon Adelson.)

In part, I deserve what I’m getting here because I’m the one who wrote the column in the first place. And I used language that was inflammatory, and so there is inflammatory language in reply. Fine. This is the way of things.

But the character of the personal assault obscures a larger cultural issue that was implied in the article (and fleshed out in the comments section later), and that large cultural issue is this: In grim economic times, large entertainment providers become more risk averse, which means that they issue more conservative music. And because there is less innovative music, the masses of listeners themselves become more accustomed to more conservative and less interesting music. And the critics, in turn, begin to review more conservative music, and like the proverbial frog in the saucepan, the critical community sometimes comes to accommodate a musical drift into the formulaic and the mundane.

As evidence of same, I adduce the following from Robert Christgau, self-appointed “Dean of American Rock Critics,” on Taylor Swift’s first album:

"You have to believe in love stories and Prince Charmings and happily ever after," declares the 18-year-old Nashville careerist. You can tell me that's worse than icky if you like; I believe in two of the three (Prince Charmings, no), and I think it's kind of icky myself. But I'm moved nevertheless by what can pass for a concept album about the romantic life of an uncommonly-to-impossibly strong and gifted teenage girl, starting on the first day of high school and gradually shedding naiveté without approaching misery or neurosis. Partly it's the tunes. Partly it's the musical restraint of a strain of Nashville bigpop that avoids muscle-flexing rockism. Partly it's the diaristic realism she imparts to her idealized tales. And partly it's how much she loves her mom. Swift sets the bar too high. But as role models go, she's pretty sweet. A-

And here’s Kate Mossman, in the Guardian, calling Taylor Swift’s "Red" one of the finest albums of 2012: “Add to this the many vulnerable poses struck by this Brünnhilde of a rockstar, this asbestos and iron-clad Amazonian of a woman, and it's clear that 'Red' is another chapter in one of the finest fantasies pop music has ever constructed."

Or Sasha Frere-Jones in the The New Yorker, or Jon Dolan at Rolling Stone (“Her self-discovery project is one of the best stories in pop”), or Michael Robbins at Spin, all polishing up this bit of musical callowness as though it were not cubic zirconium.

Come on. Let’s call this work what it is. It is music that is of minor interest. Because it’s predictable compositionally; because it’s predictable emotionally; because it markets itself to a demographic with all the subtlety that those Camel Joe cartoons once marketed to children; because the sounds are either by session hacks or are machined, and thus the sounds are free of the the thrill of players playing together; because the lyricist complains a lot; because the veneer of the contemporary now makes everything on the top 40 sound like a car commercial; and because, for all its vaunted honesty, the Taylor Swift oeuvre doesn’t tell a complex human truth. It tells a well-traveled, often self-involved, often narcissistic truth.

There are two layers to how music is evaluated in the world. There is how music is used, and there is how music sits within the history of music. I am happy, in the end, that a lot of young women like Taylor Swift. I am glad they have music they love, even if I believe they will be bored of her ultimately, just as I once was happy about the Bay City Rollers, or Sweet, or Alice Cooper, or, differently, Kiss, even though I recognized that music was kitsch.

But it’s the job of the critic to sort through the collision of contemporary music with the history of the form and to assess music based on more enduring values, which are, it’s true, partly subjective, but which also come to rest on an understanding of what music has been (a critic is a person who has been listening carefully for a long time). Taylor Swift likes to collect names of musicians she admires (e.g., The Beach Boys, Fleetwood Mac), and to drop these into the public conversation. (And she mentions Pablo Neruda on "Red," as if mere mention will make her bulletproof.) But that doesn’t mean she has what it takes to make the kind of art she admires. And the critical community, if it doesn’t call her out, gives her a pass simply because she moves units. Or so it seems to me. Which not only does us a disservice, it does her a disservice. Because how is she supposed to get better? By playing Joni Mitchell in the biopic?

You can kill the messenger, and I am happy to have as many poison darts await me, but the critical message in this case has merit, regardless of messenger, because the message is about not what works musically now, for a certain demographic, for a short while, but about what might work for everyone for all time.

Shares