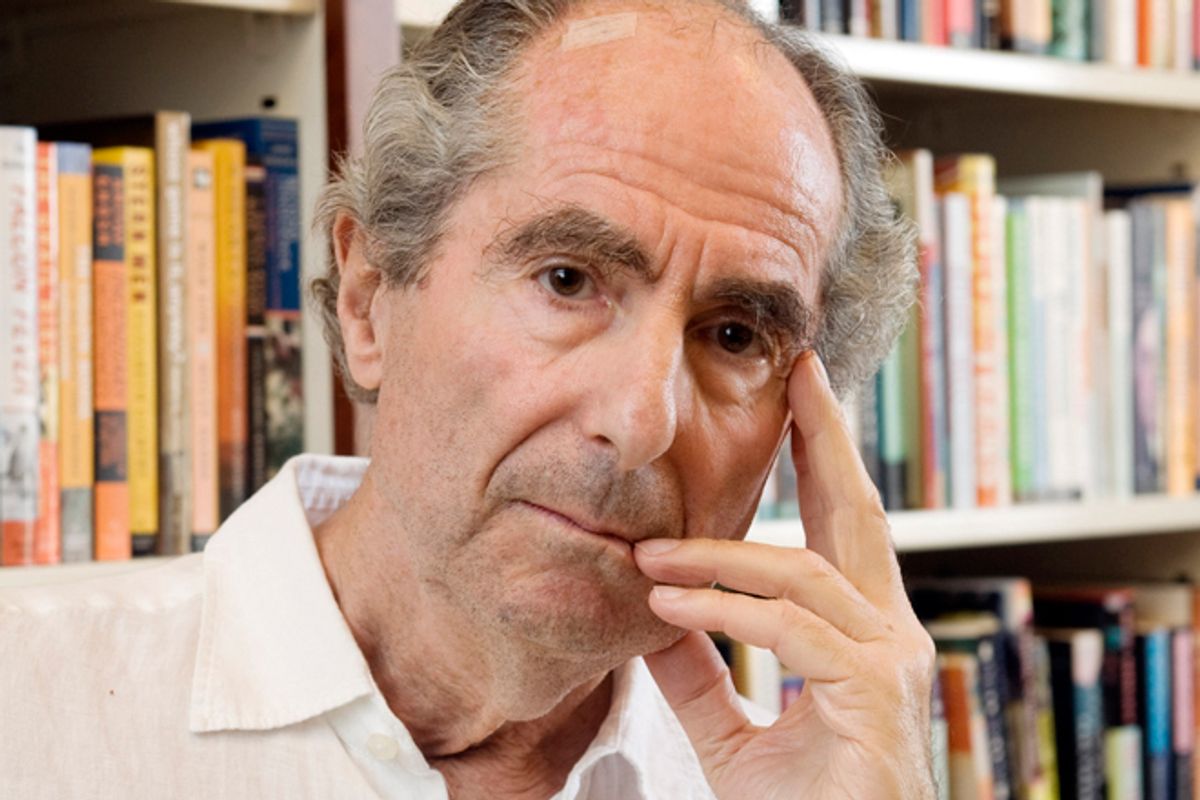

Last July, Philip Roth, the author of 26 novels and one collection of short stories, told a French interviewer that he had not written a word of fiction in three years and that he did not intend to write fiction again. Roth is 79. He told the French interviewer that he no longer felt “the fanaticism to write” that had driven him for close to six decades, and that he was “tired” of “all the work” that writing demanded. Not only would he no longer write fiction, he said, but he also would no longer read it. (Four months later, in an interview with The New York Times, Roth confessed to having recently read a novel by Louise Erdrich — under the covers, as it were — while adding that most of his reading now was in fact nonfiction.) He said he didn’t feel “any sadness” about his decision. When the French interviewer expressed dismay and wondered if Roth might not take up novel writing again, Roth said that if he were to write another book, it would “very probably be a failure,” and “Who needs to read another mediocre book?” Roth didn’t say how he would “fill the hours” (to use a phrase used mordantly by “the most famous literary ascetic in America,” Roth’s E.I. Lonoff in The Ghost Writer), other than to note that he would help his biographer, Blake Bailey, sort out the facts of his life. (Bailey is the author of a critically acclaimed biography of John Cheever, whom Roth refers to in the French interview as a friend.) It’s hard to imagine the retired Roth taking a cruise in the Caribbean, participating in the onboard karaoke nights — almost as hard as it is to imagine him tweeting — but it is possible to picture him watching sports on TV, especially baseball. In the early 1970s, he wrote a novel about baseball — he called it The Great American Novel, a title that is 95 percent ironic and five percent dead serious — and it is, among other things, the work of a baseball fan. “What,” asks the narrator of this novel, “are the consolations of philosophy or the affirmations of religion beside an afternoon’s rich meal of doubles, triples, and home runs?”

Watching baseball this fall, while I was trying to figure out what to do with my life, I asked myself the same thing. If you are the 61-year-old author of three quite minor league (and commercially unsuccessful) books of fiction and if over the past two or three years you have fielded something like 75 consecutive rejection notes and if, when you sit down at the desk in the morning, you do not detect any sign of the devotion to writing fiction that sustained you for so many years, is it time to try something else?

For much of October, I sat on the living room sofa with a jittery, middle-aged cat named Greenie (at ease only when asleep) and watched my favorite team, the San Francisco Giants, play the Cincinnati Reds and then the St. Louis Cardinals and then, in the World Series, the Detroit Tigers. Though I have never lived west of Iowa, I have been a Giants fan almost forever. In 1962, when I was 11, my parents took my sister and me on a tour of the West, which included a stay in San Francisco and two nights at Candlestick Park, where we saw Willie Mays and Willie McCovey and Juan Marichal, and where, despite the famously cold breezes off the Bay, I was totally happy, to the point that I have no recollection of the cold. (For Christmas that year, possibly as repayment for the pleasure he’d enabled me to have, I bought my teetotaler father six San Francisco Giants highball glasses — three dollars and 50 cents for the set, postage included. He had his morning milk in them.) In 2005, my wife and I honeymooned in San Francisco, and we spent a sunny afternoon in the Giants’ new ballpark, holding hands and gazing at the boats on the Bay and occasionally watching the game.

We missed by one day the debut of a now illustrious Giant named Matt Cain. Last summer, seven years later, Cain pitched a perfect game for his team. You cannot do any better than pitch a perfect game. (Even Roth’s mythical Patriot League phenom Gil Gamesh — “I’m an immortal, whether you like it or not” — could not pull it off.) Pitching one of those is like writing a perfect short story or a novel so good that even the occasional throwaway scene or line seems like another thread in an intricate design. It should also be said, lest the literary simile get out of hand, that perfect games can be a little fluky (a pitcher is often saved by brilliant fielding or even an umpire’s mistaken call), whereas a perfect piece of writing (“The Dead,” “Lady with Lapdog,” The Ghost Writer) is unassisted — and, anyway, who’s scoring?

Cain pitched like a mortal in his first four postseason starts this fall, though he was good enough to win two of those games. Even when he was mediocre, he never seemed in danger of coming apart at the seams, the way a couple of his teammates did.

One of them was a tall 23-year-old left-hander named Madison Bumgarner, whose pitching motion is so loose and slinky you’d think it must have been conceived in some Southern pasture where time moves a little more slowly. (He grew up in rural western North Carolina.) Bumgarner had two terrible starts early in this fall’s playoffs, and was then benched. When his turn in the rotation came up in the series against St. Louis, it was taken by Tim Lincecum, a slight, long-haired right-hander. On the mound, studying the hitter from under his black cap with its orange, Halloweenish SF insignia, Lincecum resembles a waifish Dickens pickpocket peeping around the corner of a building. His release is sudden and explosive — all his wiry limbs seem to jump at the hitter — and is perhaps more Droogish than Oliver Twist–like. Lincecum, who is 28, was the best pitcher in the National League in 2008 and 2009, but in 2012 he lost more games than any other pitcher in the league and had an unmentionable earned run average. Prior to his start in the fourth game of the series against St. Louis, he had twice pitched out of the bullpen, and pitched close to his old standards. But in his start, the Cardinal hitters lit him up, and he was gone before the fifth inning was done.

The problems of Lincecum and Bumgarner brought to mind a piece by Roger Angell about a pitcher named Steve Blass, who, after a full decade of success (including two complete-game World Series victories in 1971), had been “driven into retirement by two years of pitching wildness — a sudden, near-total inability to throw strikes.” The title of Angell’s piece is “Gone for Good.”

I first read this piece when it appeared in The New Yorker in June of 1975. I was going to graduate school in Iowa that fall, and going with me (in addition to assorted sacred texts: Lolita, Dubliners, V.) was Angell’s first book of baseball reportage, The Summer Game. I’d discovered this book a couple of years before in my father’s library, and it gave me more pleasure than seemed reasonable to expect from a book about sports. I thought that if I couldn’t become a fiction writer, I could try to become Roger Angell and sit in the little grandstand at Payne Park in Sarasota on warm spring afternoons and take note of the old faces under the assortment of caps. “Beneath [the caps] are country faces — of retired farmers and small-town storekeepers, perhaps, and dignified ladies now doing their cooking in trailers — wearing rimless spectacles and snap-on dark glasses.” (This comes from a 1962 piece called “The Old Folks Behind Home.”) Writing about baseball looked so easy — easier, anyway, perhaps, than trying to tell made-up stories in a voice that someone might find authentic — though it was also true that no other baseball reporter I’d ever read, or would read, could touch Angell. (The poet Donald Hall sometimes came close. Roth’s funny, word-mad, virtuoso baseball novel is another kind of fish.) Some years later, I began to notice that the sentence “Baseball is really hard” — or a variation on it — appeared regularly in Angell’s pieces. As an English major, trained to find a subtext under every rock, I thought it fair to conclude that Angell, a highly skilled fiction editor at The New Yorker as well as a gifted writer, was also saying that writing, including his own about seemingly lightweight matters, was “really hard.”

Thornton Wilder once said, “Art is not only the desire to tell one’s secret; it is the desire to tell it and hide it at the same time.” Angell, who, at 92, is still writing, with élan, about baseball and other matters, diverts us with stats and stories and pictures of a game played by men in expensive pajamas, while at the same time quietly suggesting that what is happening out in the grass before our tired, bugged-out, celebrity-obsessed, lazy, wandering eyes may tell us something about ourselves (and him). “All writing,” Angell’s stepfather, E.B. White, wrote in a 1964 letter, “is both a mask and an unveiling, and the question of honesty is uppermost, particularly in the case of the essayist, who must take his trousers off without showing his genitals.”

When “Gone for Good” was collected in Angell’s second baseball book, Five Seasons: A Baseball Companion (1977), I read it again. When, in the early 1980s, I got a job at The New Yorker and was allowed to serve as one of Angell’s fact-checkers, I read it one more time. I remember later telling Angell that it was my favorite piece of his. (I should note that by then my relationship with Roger, who had an East Coast reserve that sometimes came off as brusqueness, was close to that of a worshipper to a demigod. On the other hand, while I did admire his writing more than I could say, I didn’t suck up to him any more than Pauline Kael’s acolytes sucked up to her. I was a fact-checker, after all, and I occasionally corrected things he wrote and would also take the blame for any error I failed to catch. And, while maintaining his distance, he was often generous to me, giving me encouragement when, after I left The New Yorker, I wrote a column about sports for a fledgling magazine that would fall to earth two New York minutes after it got aloft.) There were other pieces of his that I loved more — the one about the three Detroit Tiger fans, the profile of the ferociously competitive Bob Gibson (a sort of companion piece to “Gone for Good”), the one about the 1981 Frank Viola–Ron Darling college duel, all of his sunlight-filled spring training pieces — but “Gone for Good” is deeper. It hits a nerve. It’s not simply about the decline of one very good athlete; it’s about us ordinary, striving, supposedly competent Joes failing, conclusively, right before our own eyes.

Angell describes the pre-crisis Blass as a “competent but far from overpowering right-hander,” a “control” pitcher who could get outs with an assortment of precise, off-speed stuff, “never a blazer,” and not a star. When Blass lost his control, suffering the humiliations that one suffers in so public a trade, the Pittsburgh Pirates, the team for which he won those World Series games, sent him down to the minors. Angell writes, “The distance between the minors and the majors, always measurable in light-years, is probably greater today than ever before, and for a man making the leap in the wrong direction the feeling must be sickening.” When Blass failed to find his old groove with the Charleston (West Virginia) Charlies, he left the team and consulted with pitching coaches who proposed this or that alteration in his mechanics. He tried meditation and psychotherapy and “visualization” therapy and hypnotism, but nothing restored him to who he had been just two years before. A few days after he had walked eight batters in less than one inning of a Florida spring training game, he decided to quit. He was 31, early middle age in the world of baseball.

Angell contends that Blass’s collapse is — or was, as of 1975 — unique in the history of baseball. (Good historian that he is, Angell cites other pitchers who went into career-ending tailspins, but none who’d had a decade of success before wiping out.) But then Angell has this to say about the “uniqueness” of Blass’s fall: “Sometimes, of course, what is happening on the field seems to speak to something deeper within us; we stop cheering and look on in uneasy silence, for the man out there is no longer just another great athlete, an idealized hero, but only a man — only ourself. We are no longer at a game.”

Angell repeatedly calls Blass’s failure a “mystery.” The people Angell talks to — a pitching coach, Blass’s former managers, other pitchers, the Pirates’ trainer, Blass’s wife — express bafflement or gingerly propose one theory or another. The subject of all this conjecture, Blass himself says he has “at least seventeen” theories. Angell suggests to Blass the possibility that when he fell into a slump, the slump as it persisted led to “an irreparable loss of confidence.” Angell admits that this is a circular notion, more a description of symptoms than of the affliction itself, while at the same time asserting (correctly, I think) that “fear of failure — the unspeakable ‘choking’ — is [an athlete’s] deepest and most private anxiety.” Blass dismisses this idea, saying that a pitcher can’t allow himself to think that way; fears, if they exist, can’t be acknowledged. Angell notes elsewhere in the article that the genial, modest Blass “often gives the impression of an armored blandness that suggests a failure of emotion.” (The armor that athletes wear to protect themselves from their feelings is not so different from the heavy armor that a lot of writers — see Roth’s E.I. Lonoff — don when they are away from their desks.) On the other hand, Blass’s stolidity allowed him, as Angell describes it, to have “sustained his self-regard by not taking out his terrible frustrations on [his wife] Karen and [their two] boys.”

I sat on the sofa and gazed at the baseball on TV and brooded about my life, about the work I had somehow assigned myself 40 years ago and no longer wanted to do. I recalled that Frederick Busch, one of my teachers at Iowa, once wrote on the only story I finished during my two years there, “Do you really want to be a writer?” What he meant, in his bullying, tougher-than-thou way, was: Did I have the cojones to become a writer? The evidence of this one story was that I did not, that I was a wimp. I was offended by his question, though I knew, without being able to acknowledge it then, that I was afraid of almost everything that writing fiction entailed — not simply the fear of writing so badly that I would be hooted at but the fear of looking into myself (and those close to me) and writing truthfully about what I saw. To write good fiction, one could not be “nice.” And I thought of myself as a “nice” person.

Perhaps Blass, in the course of confronting his decline, discovered (or intuited) something about himself that made the urgency of pitching a baseball seem less significant than it had been for all those years. Perhaps by watching himself fail, he understood better how to live. The pleasure of pitching well may have been gone, but why did suffering (anger, despair, an inwardness turned on others) have to fill that particular vacuum?

I brooded even as my favorite team rallied to beat the Reds and then the Cardinals, even as my favorite Giant, the plump, Mohawked Venezuelan third baseman known as the Panda (his lower lip stuffed with bamboo or perhaps only snuff), hit home run after home run after home run in the first game of the World Series against the Tigers. I might have been a happy man. (I thought of the adolescent Alexander Portnoy at the end of what he called “a perfect day,” “an exquisite day,” a doubleheader at Ebbets Field and a lobster dinner in Sheepshead Bay. The day was not done until the fanatical Portnoy could abuse himself one more time — on a bus, for Christ’s sake. Are baseball and lobster not enough to soothe the souls of us needy males?) When Lincecum and Bumgarner were called upon to pitch again, in the second and third games of the Series, they had both rediscovered their mojo. In fact, they were virtually unhittable. I love good comeback stories, even if the comeback, as was the case with the two Giant pitchers, is pulled off from something shallower than the slough of despond that someone like Blass fell into.

In his discussion of Blass and the Irreparable Loss of Confidence theory, Angell contrasts the plight of the lost pitcher with that of a troubled artist who has hit the wall and is struggling to find his “lost form.” He believes the pitcher has it tougher, inasmuch as all that matters in the end is his performance, “which will be measured, with utter coldness, by the stats.” While it is true that baseball is a meritocracy, and that nonperforming players don’t survive, it is also true that the nonperforming player of today has the benefit of the kind of gilded safety net that the corporate elite, and the rest of the one percent, have arranged for themselves. It is hard to shed a tear for some failed pitcher (such as the Tigers’ closer, Jose Velarde, whose 2012 postseason was as bad as it gets) when he is paid $9 million dollars a year — somewhat harder, anyway, than it was when the pitcher in question was Steve Blass, who, at the peak of his career, in the early 1970s, was earning $90,000 (which, as paltry a sum as it might seem now, nonetheless put Blass in the top five percent of all earners in the country).

Angell suggests that the world in which artists (or writers) work is not a meritocracy, that an artist’s fortunes depend on “the vagaries of critical judgment,” and not on cold hard stats. (For a discussion of why the literary world is not a meritocracy — and why only an “unreasonable devotion” will keep a writer going — see the poet Jeffrey Skinner’s funny, forthright The 6.5 Practices of Moderately Successful Poets: A Self-Help Memoir, published by Sarabande Books last year.) Angell’s claim is largely true — at the minor-league literary magazine level, for instance, the fate of any story or poem you submit is likely to be determined partly by fashion or politics — but it is also a fact that hard cold sales stats will have an important role in determining whether your next book will find a publisher. And it also seems not a stretch to say that writing a novel or a poem is as much of a “performance” as pitching a baseball game is — and that if your performance is judged second-rate, whether by judges fair or biased, your work isn’t going to travel far beyond your own computer screen. (Of course, you can always self-publish; whether this option is desperate or only quixotic is best known to the self-publisher.) Angell himself has surely been aware of the performance aspect of writing, as a writer with a considerable following, even if not one who, like Roth’s Nathan Zuckerman, is likely to be recognized on a Fifth Avenue bus. On a bulletin board in his Maine house, alongside a note from John Updike instructing him not to fall in love with his own prose, I once noticed a quotation from the French novelist and journalist Anatole France, an exhortation to the effect of, “Anatole, your fans await your next one! Get to work!”

¤

“Gone for Good” begins with a description of a photograph that caught Steve Blass ecstatically aloft (his feet are well off the ground) after he got the last out of the 1971 World Series. Joy like this, particularly as expressed by an adult, is something to behold, a reminder that one goal of playing a game like baseball, even if you are a gazillionaire, is a simple emotion. You see some variation on this picture every late October, but it never gets old. I witnessed it again last fall after the Giants’ skinny, black-bearded closer, Sergio Romo, got the final Detroit batter to strike out. I liked seeing Romo airborne for that split second, and I liked the celebratory dogpile that immediately followed, with each of those twentysomething and thirtysomething Giants as happy as, say, a laughing kindergartener spinning and soaring on a tire swing at a playground.

I headed for bed, stopping at a bookshelf where Roth’s The Counterlife abuts John Cheever’s Oh What a Paradise It Seems. Cheever is what I thought I wanted that night, a writer who knew something about joy if not a lot about baseball. I picked Bullet Park (1969), which I’d first read in the summer of 1977 — the summer I also inhaled Angell’s Five Seasons. I’d fallen in love with Cheever’s writing then — his beautiful, elegant, classically clean sentences that give us indelible truths about sunlight and thunder and the seashore (“thalassa, thalassa,” his ocean waves say as they roll up on the beach); his satire that can be as wickedly sharp and as self-lacerating as Roth’s; his playfulness; the leaping, surreal, fairy tale turns in his plots — and I have continued to read him.

I chose Bullet Park partly because at the center of it is a person, a suburban New York teenager named Tony Nailles, who retires to his bedroom for months because he is “sad.” Cheever writes with great wit and compassion about Tony’s fate and that of his two bumbling, foolish but loving parents, Eliot and Nellie, and about how the Nailles inevitably become involved with a dark-hearted Bullet Park arriviste named Paul Hammer. (There is more than a hint of Lolita — and the Humbert Humbert–Quilty showdown — in Bullet Park.) The novel may be guilty of the occasional throwaway line or passage, but it comes close to being a perfect little tragicomedy, and it is so beautiful and spirited that you feel a little like Paul Hammer falling in love, walking the streets of New York, “so high that [his] ears were ringing.” You don’t want the book to end, but Cheever wrote a novel — and how un-21st-century it is in its brevity! — that delivers an ending that he has been guiding us toward for 240 pages.

The night the Giants won the Series, I reread the scene where the Nailles recruit a locally famous "swami" named Rutuola to heal their “sick” son. All the other more traditional therapies have failed, and the mystery of Tony’s illness has led to fractures in his parents’ happy marriage. (Eliot has taken to copping tranquilizers from a dealer who likes to meet in cemeteries.) When Swami Rutuola, a black man, arrives at Tony’s house, he tells Tony stories about how he got his “bad eye” (he says he will hold his head in the shadows so that Tony will be spared the sight of the eye) and how once in Grand Central Terminal, where the swami cleaned bathrooms at night, he helped a man who thought he was dying by chanting the word “valor” with him. The swami heals Tony, too, by leading him through chants (or “cheers,” as he calls them, because Tony once played football) that are pure Cheever. “It’s crazy,” Tony says to the swami, “I know it’s crazy, but I do feel much better.”

Cheever is not being ironic here. There is nothing bogus about his healer, even though the author makes sure we understand the swami isn’t a paragon in flowing robes. (We first see him reupholstering a chair in a shabby apartment above a funeral parlor, giggling with his girlfriend.) Love and imagination are forces for change in Cheever’s fiction. Cheever wrote his novels and stories because his imagination and his love of the act of writing drove him to. His many personal miseries didn’t stop him. Allan Gurganus, who was Cheever’s student in the early 1970s, recently wrote in The New York Review of Books, “Even as we read [Cheever’s stories] today, all are still guided by, puppeteered, and deified by one confused pansexual 130-pound alcoholic husband and father, not yet allowing himself to sneak off in stocking feet and snitch an 11AM snort from the pantry, a reward, for another morning spent earning his way into the promised world denied him, while carrying on his back — his family, his lies and addictions, his fugitive sex, his hopes, his genius, and, of course, his beneficiaries, all the readers left alive on earth.”

In The Ghost Writer, the young Nathan Zuckerman notices during his visit to E.I. Lonoff’s house a quotation from Henry James that is pinned to a bulletin board in the great man’s study. It says, “We work in the dark — we do what we can — we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.” Zuckerman, brimming with devotion and ambition, questions that final assertion. “The art was what was sane, no? Or was I missing something?”

Zuckerman was missing something: the insanity of spending a life, as his idol Lonoff puts it, “turning sentences around.” As Lonoff’s wife says of her famously ascetic, scrupulous, fanatically driven husband, “Not living is what he makes his beautiful fiction out of!”

¤

When I read last fall that Roth had decided to stop writing fiction, I thought it was an entirely sensible, even brave, decision. I had thought that his novels of the last decade were nowhere near as good as so many of those that had preceded them, and his interview with the French magazine suggested he knew that was so. But what clearly mattered most in his decision was that he no longer felt the need (or fanatical desire) to write fiction. Graham Greene, who wrote about faith and doubt and self-betrayal as deeply as any novelist of the 20th century, said, “The creative act seems to remain a function of the religious mind.” Roth wasn’t going to try to fake it; if you are serious, you can’t fake devotion.

During my own brooding about whether to go on, I tried to be honest about what my writing meant to me. Was my despair perhaps only garden-variety self-pity? Was I going through one of those periods when I would lose all faith and all confidence and yet, somehow, months later, start again? Were not those depressions, in some circuitous way, useful to my work, maybe even necessary? Had I not sometimes, even during the last three years when everything I’d written had been rejected, felt some joy while turning sentences around and around? Was it not a pleasure to write the occasional sentence that, prior to writing it, I had no idea was inside me, a sentence that could make all the tedium and grind of writing tolerable? Had I not felt some solace the other day when a friend who had read my books told me that his wife had been moved to tears by one of my stories? Was that alone not reason enough to go on? Was my ego so fragile that I could not endure another three years of rejections before some story would reach a reader who would connect with it? Would I be depriving myself of joy and self-knowledge by leaving the field, by giving up?

On the other hand, didn’t Lonoff’s wife have a point? If I gave up writing fiction, would I not also spare my own wife and children my moods, the despair, the anger hidden in my silences? (The joy that I would sometimes experience while writing was, alas, entirely private, and rarely survived beyond the moment. And while I had become somewhat adept at separating my work from my life, all those turndowns did eat away at me and did lead me to imagine that I was in the midst of a certain cognitive decline, that the skills I’d once apparently possessed were no longer available.) Would I not also spare those close to me the pain of seeing their lives, or some aspect of their lives, fictionalized, distorted, exploited? If, to use E.B. White’s metaphor, I was going to take my trousers off, didn’t I have to be willing to accept all the consequences — the stares, the cackles, the indifference, the silence? And was I not, at 61, at a point in my life where I still had time to do something else, whether it be some other form of writing or even work unrelated to writing? Were there not other paths to joy and, perhaps more important, paths to being useful to others in ways that writing fiction simply cannot be? Perhaps as, say, a tutor in the public schools, I could do more valuable work than I could ever hope to do as a writer of fiction.

That night, I decided that in the morning, after I got my daughter off to kindergarten, I would sit at my desk and write this essay about writers I loved and young multimillionaire baseball pitchers in slumps. What I would do the morning after I finished this essay, I didn’t know, but I was no longer in possession of the “unreasonable” devotion to writing fiction that you can’t be without if you’re going to go on.

¤

Shares