Hello, Academy members – you’re about to make a mistake. Not quite a world-historical, “day that will live in infamy”-type mistake on the order of “Crash” or “Dances With Wolves” or the lifetime snubbing of Stanley Kubrick, but a mistake nonetheless. You’re about to give your best-picture award to Ben Affleck’s movie “Argo” – or so everyone thinks right now; we’ll get to the doubt and wild speculation in due course – and it’s just not that good. I mean, look, it’s not terrible, and there are plenty of years when we’d be grateful for that. Your average barstool commentator could probably identify at least half a dozen best-picture winners that are clearly worse. (I won’t pretend that I’ve seen, say, “The Life of Emile Zola,” from 1937.)

Being a non-great film that wins Oscars is hardly a crime; it’s barely a news event. But it’s the way that “Argo’s” not great that bugs me. In a year full of big, ungainly, ambitious movies that wrestle with questions of history, morality and philosophy, “Argo” is less than the sum of its parts. It has repeatedly been praised for being “just a movie,” in obvious contradistinction to the complicated and problematic truth-telling goals of “Lincoln” and “Zero Dark Thirty” – but what is that supposed to mean? It means that Affleck and screenwriter Chris Terrio have taken a minor but intriguing historical episode drawn from the Iranian hostage crisis and rendered it into a reassuring and familiar action-adventure flick about American heroism and, not coincidentally, the inspiring patriotism of the apparently cynical bastards in the film industry.

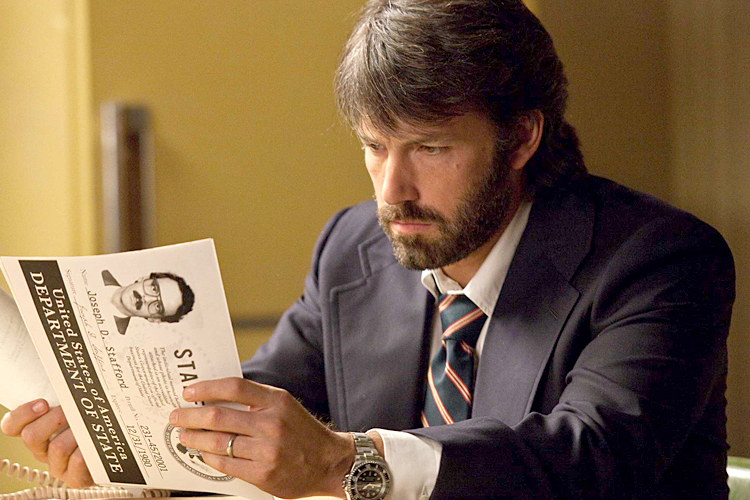

If Affleck captures one of the darker and more chaotic periods of recent history in meticulous detail – and his replication of the revolutionary streets of Tehran, and the seizure of the United States embassy, is genuinely impressive – I would argue that’s all elaborate window dressing for a propaganda fable. (Massive spoilers ahead: There’s no way to discuss this without directly addressing what happens in “Argo” and how it departs from actual events.) It’s true that CIA agent Tony Mendez (played by Affleck in the film) successfully “exfiltrated” six Americans who’d been hiding out in the Canadian embassy in Tehran, using the outrageous cover story that they were a Canadian film crew scouting locations for a “Star Wars” knockoff. But almost none of it happened the way we see it in the second half of “Argo.”

The Americans never resisted the idea of playing a film crew, which is the source of much agitation in the movie. (In fact, the “house guests” chose that cover story themselves, from a group of three options the CIA had prepared.) They were not almost lynched by a mob of crazy Iranians in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar, because they never went there. There was no last-minute cancellation, and then un-cancellation, of the group’s tickets by the Carter administration. (The wife of Canadian ambassador Ken Taylor had personally gone to the airport and purchased tickets ahead of time, for three different outbound flights.) The group underwent no interrogation at the airport about their imaginary movie, nor were they detained at the gate while a member of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard telephoned their phony office back in Burbank. There was no last-second chase on the runway of Mehrabad Airport, with wild-eyed, bearded militants with Kalashnikovs trying to shoot out the tires of a Swissair jet.

All that is supposed to be dramatic license, “just a movie,” “based on a true story” vs. actually attempting to tell the truth. I get it. But I’m less concerned with the veracity of individual details than with the fact that “Argo” uses its basis in history and its mode of detailed realism to create something that is entirely mythological. It’s a totalizing fiction whose turning points are narrow escapes and individual derring-do designed to foreground Affleck and his star power (instead of the long, grinding work of Canadian-American collaboration behind the scenes that made the real rescue possible), an adventure yarn whose twists raise your pulse rate but keep the happy ending clearly in view. It turns a fascinating and complicated true story into a trite cavalcade of action-movie clichés and expository dialogue, leaving us with an image of the stoical American hero (or the Mexican-American hero played by a white guy, anyway) framed in a doorway with a blonde in his arms and the flag flapping behind him. I’m not being metaphorical, by the way; that’s the final shot of Mendez’s homecoming scene.

As literary critic and New York Times columnist Stanley Fish has noted, in form “Argo” is a standard caper flick that demands no reflection or introspection and deliberately “doesn’t linger in the memory.” If you do start to think about it, though, the whole thing falls apart. It’s also a propaganda movie in the truest sense, one that claims to be innocent of all ideology. Affleck and Terrio are spinning a fanciful tale designed to make us feel better about the decrepit, xenophobic and belligerent Cold War America of 1980 as it toppled toward the abyss of Reaganism, and that’s a more outrageous lie than any of the contested historical points in “Lincoln” or “Zero Dark Thirty.” It’s almost hilarious that the grim and ambiguous portrayal of torture in Kathryn Bigelow’s film – torture that absolutely happened, however one judges it and whatever information it did or didn’t produce – was widely decried as propagandistic by well-meaning liberals who never noticed or didn’t care about Affleck and Terrio’s wholesale fictionalization.

One factor is that “Argo” applies a faint left-center gloss to its patriotic fantasy, acknowledging early on that the Iranian revolution of 1979 was partly blowback from the CIA-sponsored coup that had toppled prime minister Mohammed Mossadegh 26 years earlier, and adding a concluding voiceover from Jimmy Carter. So its propaganda is largely agreeable to its target audience, and is hence perceived as not propaganda at all. Another is that “Argo” is a self-smooching gift from the film industry to itself, a likable mainstream hit that possesses what critics sometimes call “movie-movie” qualities. It’s a real movie about a fake movie that makes a few lightweight observations about the similarities between spycraft and moviemaking, the two greatest let’s-pretend businesses of our age.

Are there other options for the Academy at this point? Well of course there are, but I don’t see any of them as realistic. In fact, the ways that “Argo” distorts reality and history into an inspirational fun-fest that leaves audiences high-fiving each other and humming the late ‘70s hits of the soundtrack turns out to have been devilishly clever. It’s the movie that hasn’t conspicuously pissed anybody off (see ya, “Lincoln” and “ZDT”), that isn’t too dark and European (“Amour”) or too weird and indie-ish and racial (“Beasts of the Southern Wild”). Most of all, it’s the movie that paints the movie business and movie people in a flattering light, a strategy that almost never fails. (See also: “The Artist,” 2012 Academy Awards.)

Then again, I’m the guy who told you a few weeks ago that “Lincoln” was a shoo-in, and might sweep all the major awards. As usual in Hollywood, nobody knows anything, and that sound you hear in the background is veteran Oscar-watchers beginning to hem and haw and hedge their bets all over the place. Roger Ebert recently wrote that he feels the momentum shifting toward David O. Russell’s “Silver Linings Playbook,” and that’s not an utterly outrageous suggestion. There’s definitely a mounting degree of anti-Affleck backlash out there, and it has to coalesce around something. Russell’s vaguely offbeat rom-com, which I enjoyed perfectly well but can barely remember beyond Robert De Niro’s supporting performance, has two great advantages. It makes absolutely no claim to have anything to do with real events (except insofar as mental illness and the Philadelphia Eagles both exist) and it’s the only nominated film that’s arguably even more trivial than “Argo.”