The love letters of Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz number upwards of 25,000. It’s such a prolific amount, it makes you marvel that they had any time at all to live the lives they did. The first published volume of their correspondence is some 700 pages, and it captures all the intimacies and intangibles one suffers for, because of, or in spite of love. It is also a valuable source of art history, self-help, bad spelling, and indulgent use of the em dash.

My Faraway One, as the volume is called, titled after an oft-used sobriquet of theirs, encapsulates a way of looking at the world that speaks directly to the art O’Keeffe and Stieglitz produced. The book is an expression of the indelible influence they had upon each other, and upon modern art.

Like all great epic poems (because love letters are nothing if not poetic), the writing is both tacky and penetrating, and captures the sort of anxiety and misanthropy that often accompany the creative mind. Referring to numerous people as “great stains” on the world, O’Keeffe’s letters in particular emphasize the artistic vocabulary of her paintings. “Goodnight,” she writes to Stieglitz, “I hope the stars are very bright — tonight — the sky very clear — I want it to be very still so you can just hear the water —.” This may sound sentimental and schmucky, but one cannot — after reading 700 of such letters — be cynical of their incorruptible desire to describe the world to one another.

It makes you wonder how much richer your experience of life would be if you had to rehash every day of it to someone else, constantly searching through your yesterdays to find something beautiful to tell you lover today. The way they describe life! This is the poetics of remembering, of making remembrance a daily ritual.

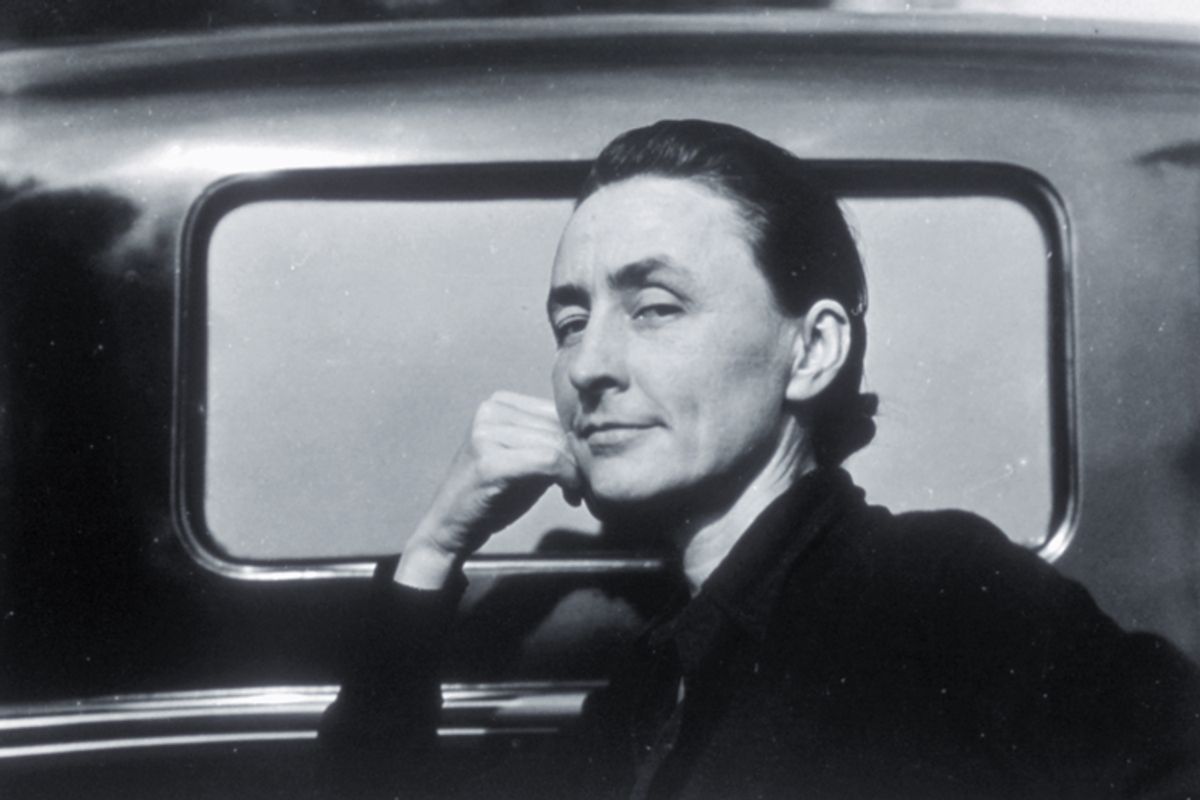

Photograph of Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz kissing at Lake George (image via Yale University Library)

In some ways, reading the love letters of other people is a perverted, Peeping Tom thing to do. But eavesdropping in this way gives an uncanny, almost inside-joke quality to the events that are its backdrop: After a dinner party on West 67th Street, Stieglitz writes to O’Keeffe:

Duchamp having his studio a flight up, he took me up to see his work — He is doing a marvelous thing on a huge glass — about eight feet by twelve — Has been over a year on it — it’s all worked with fine wire and lead — a little color — very perfect workmanship — He has a beautiful soul.

A marvelous thing on a huge glass. Indeed.

Missives like this function on many levels, not just offering context for the lives of O’Keeffe, Stieglitz, and their friends, but underlining what it’s like to love art for its own sake. They create a kind of nostalgia for what looking at art before the market boom must have been like. Stieglitz often refers to the souls of the artists he admires most, O’Keeffe notwithstanding, with words like “big” and “honest.” He also tends to capitalize things like Trees, Clouds, Woman et al, stressing his existential sensibilities (and the things he photographed most) as well as his German heritage (capitalization is a fond trope of the German poets).

As World War I becomes a reality, the modernist zeitgeist becomes palpable in their letters, edging into what would become a postmodern riff. “It made me fear for the children,” Stieglitz writes:

A sign or age — Or what? — I who sang the praises of the growing city — loved the huge machine — the developing of it — Tonight — I felt nothing of all that — merely sat there in the rolling machine and stared — and stared — and wondered. And felt no joy — No creative joy.

At the beginning of the war, O’Keeffe is working as an art professor in Texas. She succinctly describes her distaste for war as “sending cattle to market.”

Detail of a letter by O’Keeffe

The book goes on to chronicle their love affair, marriage, and eventual geographic separation. O’Keeffe was fiercely independent and solitary in nature, and, tormented by Stieglitz’s later infidelity, she moved back to the southwest. Her clemency and unconditional love for him are both infuriating and admirable, although she refused to live with him in New York.

Stieglitz is the man largely responsible for bringing photography into the 20th century and European modern art to America; O’Keeffe, an artist-turned-household-name before the pageantry of the later art stars. But much more than an expression of their life together, My Faraway One offers a gentle reminder of what it is to be a human and a lover — and the difficulty of both.

My Faraway One, edited by Sarah Greenough, is available from Yale University Press and other online sellers. Both Stieglitz and O’Keeffe have work in the current Museum of Modern Art exhibition Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925, with an emphasis on their symbiotic relationship.

Shares