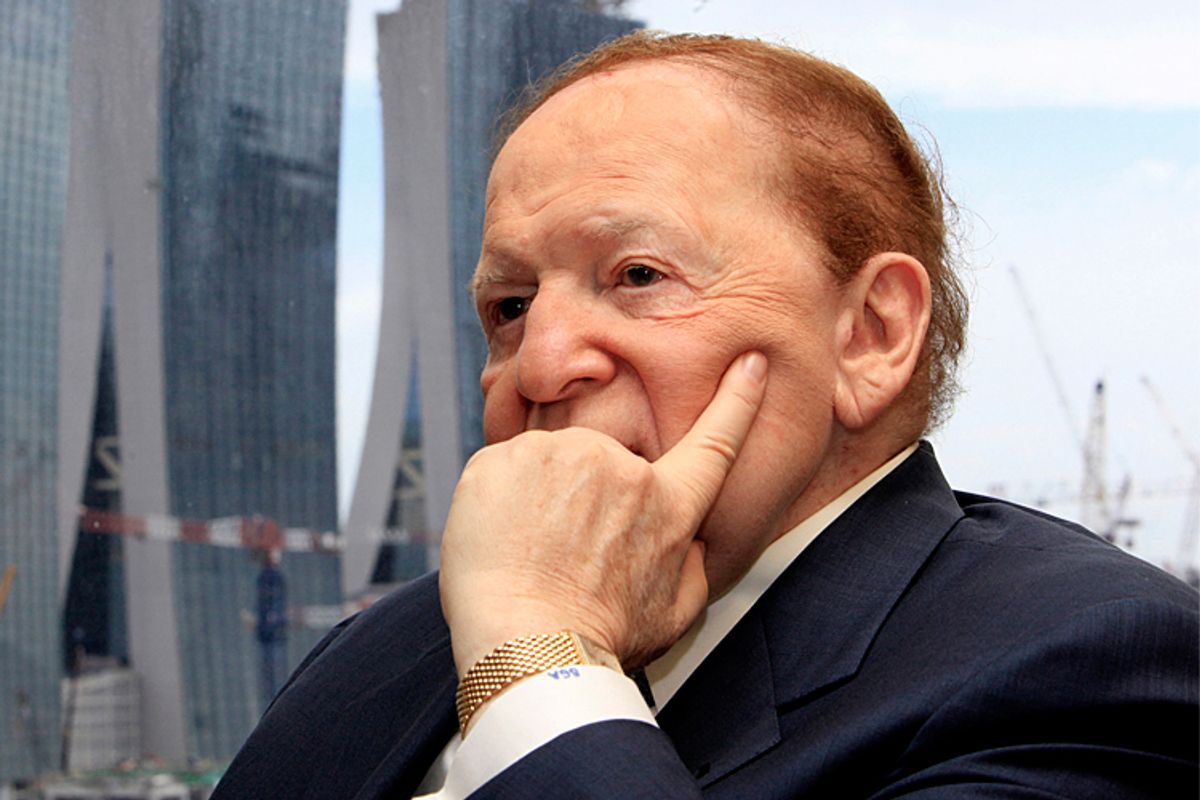

Casino mogel Sheldon Adelson is the GOP’s biggest single donor, spending between $98 million and $150 million on the 2012 election cycle alone and promising to give even more the next time around.

Why would Adelson spend so much money so haphazardly? Instead of spreading his wealth around or investing in candidates with the strongest win potential, Adelson did things like spend $20 million on Newt Gingrich, pumping in more cash even after it was clear he was going to lose?

For years, it’s been rumored that Adelson’s spending is, in addition to supporting his neoconservative ideological agenda, an attempt to insulate himself from looming government investigations into reported corruption at the Chinese holdings of his Las Vegas Sands Casino empire.

There have been reports of ties to Chinese mafia, money laundering, organized prostitution, and lawsuits from former partners.

But what was really said to worry Adelson is alleged violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, a U.S. law that holds American companies liable for bribery committed by their foreign subsidiaries. There have been reports of FCPA violations at Adelson’s Chinese Macau casinos for years, but he’s denied all of them, and never hesitated to sue journalists who write negative things about his businesses, sometimes to the point of bankruptcy.

Now, however, in a stunning disclosure, Las Vegas Sands has acknowledged in SEC filings that it probably violated the American anti-bribery law:

After the Company’s receipt of the subpoena from the SEC on February 9, 2011, the Board of Directors delegated to the Audit Committee, comprised of three independent members of the Board of Directors, the authority to investigate the matters raised in the SEC subpoena and related inquiry of the DOJ.

As part of the annual audit of the Company’s financial statements, the Audit Committee advised the Company and its independent accountants that it had reached certain preliminary findings, including that there were likely violations of the books and records and internal controls provisions of the FCPA and that in recent years, the Company has improved its practices with respect to books and records and internal controls.

This is also the first time Adelson’s company has acknowledged being under investigation, confirming probes from both the SEC and Department of Justice.

Here’s why this would trouble Adelson so much: “Under federal law, individuals or companies that aid or abet a crime, including an FCPA violation, are as guilty as if they had directly committed the offense themselves.” In other words, Adelson’s Las Vegas Sands or even Adelson himself could be held in violation of the FCPA if the government can prove that they directed officials to make bribes or even if they covered up accounting anomalies to hide the bribe.

Why would Adelson think some campaign money could turn down the heat?

Because he’s done it before. In 2001, Adelson and a colleague flew to Beijing to meet with Chinese officials they were trying to court. Adelson wanted the government to allow more gamblers to Macau, where his casinos were based, and was looking to make a deal.

Chinese leaders were worried about a resolution in the U.S. House of Representatives that would direct the U.S. Olympic Committee to vote against China’s bid to host the 2008 Olympic because of its human rights record.

When he learned about this, Adelson called up former Republican Majority Leader Tom DeLay, who got back to him just a few hours later to say not to worry. “So you tell your mayor it can be assured that this bill will never see the light of day,” DeLay said, according to the New York Times. The next day, Adelson asked for the change he wanted in Macau.

And there is already a conservative campaign underway to gut the FCPA. Beginning in 2010, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce made a big push to relax the anti-bribery law in some key areas. A lengthy report from the group details amendments they would like to make to make it more businesses friendly.

Coincidentally or not, Las Vegas Sands holds a seat on the Chamber’s board of directors.

Shares