Forty-eight years to the day after Bloody Sunday, a seminal tragedy that paved the way for the Voting Rights Act, there are key lessons we must remember and heed, in order to strengthen that now-threatened legislation.

Every year, as February turns to March, thousands return to Selma, Ala., to commemorate the moment President Lyndon Johnson later compared to Lexington and Concord, calling it “a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom.” But few know that this important event was the result of a series of accidents and almost did not occur. More important, it suggests that change in America is not inevitable and comes only when determined people risk their lives to achieve it.

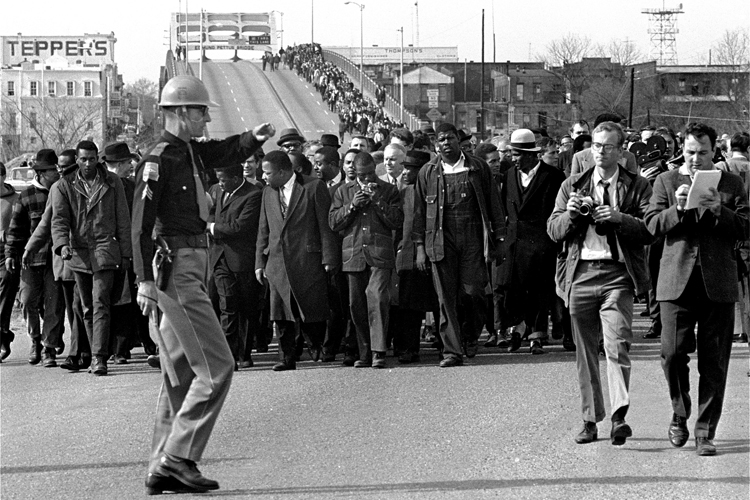

On Sunday, March 7, 1965, peaceful demonstrators attempting to cross Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge were attacked by Alabama State troopers armed with bats, electric cattle prods and tear gas. “I’m going to die here,” thought John Lewis, one of the march’s leaders, as he fell to the ground, concussed by a trooper’s bat.

News of the tragedy shocked the nation. Thousands joined Martin Luther King’s voting rights campaign in Selma and others called on President Johnson to immediately send a voting rights bill to Congress. Ten days later, he did and it was signed into law on Aug. 6, 1965, immediately giving thousands of disenfranchised African-Americans the ability to vote and eventually transforming American democracy itself.

While Selma, Ala., is recognized as “the spiritual home of the Voting Rights Act,” events in a small town named Marion actually led to the march on Bloody Sunday, the crucial event that intensified the president’s desire to push immediately for a voting rights act. The march that became an iconic event was almost canceled and, when it occurred, Martin Luther King, whose movement benefited the most from the tragedy, was not even there.

King began his voting rights campaign in Selma in January 1965, hoping that Sheriff Jim Clark would react with a show of force that would touch the nation’s conscience and move LBJ to place a voting rights bill at the top of his ambitious Great Society agenda. Clark did not disappoint: he battled with a 50-year-old would-be voter named Annie Cooper, losing his hat, tie and badge in the melee; he dragged Amelia Boynton, leader of Selma’s Voters League, through the streets and tossed her into a police car; he jailed thousands of demonstrators, and forced high school students to run out of town; those who fell behind were beaten with cattle prods. While the nation’s newspapers and evening news programs covered Clark’s brutality, nothing moved the Congress or the president to act. King was so discouraged that he considered leaving Selma for more fertile territory.

One such spot was Perry County where local activists like Marion’s Albert Turner had long been working for voting rights and African-Americans had recently launched a successful boycott of segregated white businesses. Hoping to destroy the Marion movement, local police and Alabama state troopers viciously assaulted a group of demonstrators (as well as white reporters who were covering the event) on the night Feb. 17, 1965. A young activist named Jimmie Lee Jackson, trying to protect his mother from a group of angry troopers, was shot and later died from his wounds.

President Johnson and Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach hardly acknowledged the tragedy. Katzenbach said only that the FBI was on the case — a not very encouraging response, given the agency’s history of hostility toward the civil rights movement. Indeed, J. Edgar Hoover had informed Katzenbach that the Marion riot was “grossly exaggerated,” that there was “no truth to the statements that Negroes have been brutally assaulted.” Apparently, the administration believed Hoover’s report that there had been “no police brutality but only the use of force necessary to handle an unruly mob.” The evening news programs showed no film, and America’s most influential newspapers published no photographs to prove Hoover wrong.

Turner and his colleagues were so angry that they wanted to carry Jackson’s coffin to Montgomery, home of the state’s governor, George Wallace. Eventually, it was decided that a group from Marion and Selma would march to Montgomery and present the governor with a list of their grievances. But Wallace announced that he would not permit “a bunch of niggers to walk along a highway in this state as long as I am governor,” and ordered state troopers to block them if they tried to cross the bridge linking Selma to the Jefferson Davis Highway.

The event that would soon transfix the nation began as a comedy of errors. Learning of Wallace’s plans to stop the marchers, and fearful of violence and perhaps his own assassination, Martin Luther King Jr. told his advisers on the night of March 6 that he thought it might be better to postpone the march until tempers had cooled and preparations for the 50-mile journey were arranged. Most agreed except for two of King’s toughest field generals, James Bevel and Hosea Williams, who wanted to march. A worried and uncertain King asked for a little more time to make up his mind.

Early the next morning King had decided — he hurriedly sent his aide, Andy Young, to Selma to cancel the march. When Young’s car reached the Edmund Pettus Bridge, he saw an ominous site: hundreds of state troopers, city police and Clark’s forces on horseback already in place. At Brown Chapel, the movement’s headquarters, he received another shock — 600 people, men, women, teenagers, and even children preparing to march. Among them were the heartbroken but determined people from Perry County, wanting to honor Jimmie Lee Jackson. He cornered Hosea Williams, asking why he had not followed King’s order to postpone the march. Williams said that King had “reauthorized the march” during a conversation with Jim Bevel that morning. Young searched frantically for Bevel and when he found him, Bevel claimed that King had changed his mind. There is no evidence that he had and it appears that Bevel, perhaps King’s most emotionally volatile adviser, disobeyed his leader’s orders.

Young decided to telephone King himself, who was preaching at his father’s church in Atlanta. “[A]ll these people are here ready to go now,” Young told King. “The press is gathering expecting us to go, and we think we’ve just got to march, even if you aren’t here. There’ll probably be arrests when we hit the bridge.” King reluctantly gave his assent.

And so, at 2:18 p.m., after a prayer and the singing of “God Will Take Care of You,” the 600 set out with Hosea Williams and John Lewis in the lead. They weren’t really planning to march to Montgomery, no one was ready for such a long journey. A night in jail was probably in their future so Lewis filled his backpack with everything he needed to pass the time—something to read, an apple, an orange, in case the prisoners were not fed, and a toothbrush and toothpaste. Earlier, King had said, “We will write the voting rights law in the streets of Selma.” But, in fact, it was written by the bruised and tear-gassed marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Bloody Sunday rescued King’s failing campaign. It sadly suggests that fundamental change in America only comes as a result of a critical event that changes public opinion and forces politicians to act. But it also indicates that a determined, well-organized and nonviolent crusade can succeed in achieving its goals. The desire of African-Americans to vote was greater than cattle prods, tear gas and baseball bats. Similarly, recent attempts to prevent minority voting by requiring voter ID cards, cutting back on early voting, and obstructing registration actually energized those who were threatened, resulting in another mass movement, which stood in long lines and waited patiently for hours to reelect their candidate — President Barack Obama.

Now the act faces its greatest challenge in the Supreme Court. During oral arguments in Shelby County v. Holder on Feb. 27, 2013, the court’s conservative majority openly questioned whether the act was still necessary. History suggests that if the Supreme Court does weaken the act, it will only be a temporary setback. Just as Bloody Sunday had produced a national consensus that supported the creation of the act, a 5-to-4 Supreme Court decision that emasculates it may well produce a similar movement to strengthen it.

“I have no despair about the future,” King had written from the Birmingham jail 50 years ago this year. “We will reach the goal of freedom … because the goal of America is freedom.” King was only partly right. Winning rights long denied is not inevitable; it comes only when determined Americans commit themselves totally, as did the men and women who risked their lives on the Edmund Pettus Bridge 48 years ago today.