A 2007 federal ban against equine slaughterhouses followed a nationwide outcry over the federal government’s roundup of some wild horses, which wound up on the killing floor. Such things had happened many times over, but this time, in a different age, the atrocities were under more intense scrutiny. The term “atrocities” is not hyperbole, as witnesses to what goes on in and around slaughterhouses have stated.

The ban lapsed in 2011. But ever since it was enacted, there were efforts to reopen “rendering plants” for horses, and in recent weeks, they seem to have finally succeeded. A bill to authorize slaughterhouses in Oklahoma is advancing quickly, and New Mexico is now trying to harvest what some view as an untapped cash crop. The states will need the USDA to once again agree to inspect the plants and their horsemeat, and reports suggest that the USDA is poised to do just that. The White House, meanwhile, has asked Congress to reinstate the ban, and some representatives are starting to speak up in support, as Rep. Jim Moran, D-Va., did Friday.

But the horseflesh industry has been around since the advent of the train and car. By the end of the 19th century, the horse had outlived its usefulness -- except for being money on the hoof. At the time, there were about two million mustangs running the range, as well as countless other horses across the country -- carriage horses, plow horses, war horses and more. As I document in my book “Mustang: The Saga of the Wild Horse in the American West,” hundreds of thousands of wild horses were driven up the cattle trails right to the plants in Chicago, and they were then shipped to Europe in tin cans or to California as chicken feed for the thriving poultry industry. The railroad even had a special rate for such shipments.

One rendering plant in particular processed most of the horses, figuring prominently in the plundering of the West. This was the country’s first major equine slaughter operation, started in 1923 by the notoriously dapper Englishman P.M. Chappel and his brother, Earl. The Chappel Brothers Corporation, or CBC, rendered so much meat that it was known among cowboys as “the Corned Beef and Cabbage.” In its first year, as Walker D. Wyman reports in his seminal book “The Wild Horse of the West,” “about half the 1,446 horses processed under federal jurisdiction were canned, and it is certain most of them were wild.” The result was 149,906 pounds of meat from the Chappel plant alone; the total yield from the nearly 200 plants that were operating across the country that year was 22,932,265 pounds.

In 1925, Montana entered the market, signing a death warrant for “abandoned horses running at large upon the open range.” Over the next four years, about 400,000 mustangs were removed from the state. On June 5, 1929, a New York Times reporter filed a heated account of the round-ups, foreshadowing the mistaken reports that are published today, often restating such government canards as "wild horses must be removed because of drought conditions" even though no other wild animals are taken from the range for the same reasons and cattle continue to graze freely in great numbers.

“The first chapter has been written in the greatest wild horse roundup ever held in the West,” the Times reported, “and today hundreds of horses -- large and small, vicious and indifferent, mustangs, ‘fuzz-tails’ and bronchos -- are in pastures ready for the first sale and elimination check. The roundup will continue through most of the summer, with the hardest work still ahead, for the horses are retreating.”

During the decade that I worked on “Mustang,” I came across an obscure account of what it was like to work on the front lines of the horseflesh industry. Called “I Herded the Wild Ones,” it was written by Adolph C. Kreuter, a cowboy who toiled in the Chappel corrals, and it appeared in Frontier Times:

Ladies were demanding pony coats, in the manufacture of which the hair side was used much as the hide of unborn calf is used in some western apparel. Frequently as many as 500 to 700 horses daily were being sashayed up the ramp to the killing floor. I heard that this was very often done with great difficulty, due to the spooky natures of the condemned.

Buried in his article is the story of an anonymous cowboy who worked at the Chappel plant and couldn’t take it. After a series of failed attempts to destroy the plant, his efforts became more extreme. Once, he climbed a telegraph pole and cut the wires, sending off huge flares of flashing light -- an SOS seen for miles. That did not end the slaughter, and he tried again, this time attempting to blow the place up, injuring himself in the act. He fled, and the following day some children playing in the grass near the slaughterhouse found him. He was arrested and charged with attempting to destroy the plant.

“I plead guilty,” he said. “I couldn’t help it. I am a cowboy, and I love horses. I can’t bear to think of people eating them.” Later, he reportedly went insane and then disappeared from the record. Chappel himself died in a freak accident -- like others who have trafficked in the misery of horses, as some who have worked on the front lines of the fight for wild horses have told me, and as I have noticed myself over the years.

You could even include George Armstrong Custer in this observation. As we all know, he went down in an infamous "last stand" at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Eight years prior to that battle, on Thanksgiving night, he led the cavalry in the attack on Black Kettle and his band of Cheyennes along the Washita River. After Black Kettle and his tribe were wiped out, Custer ordered the decimation of the pony herd -- all 800 of them, the mules as well. "We tried to rope them and cut their throats," Lt. Godfrey recalled. "But the ponies were frantic at the approach of a white man, and the horses were frantic. My men were getting tired, and I called for reinforcements ..."

"And so the rest were shot, and later," as I recount in "Mustang," "as the Cheyenne woman Moving Behind, 14 at the time, remembered, the wounded ponies passed near her hiding place, moaning loudly, just like human beings." Today, the site of the Battle of the Washita is a national historic site.

For several more decades in the 20th century, the killing of horses for profit was a widespread industry, and the men who rounded up wild horses for the commercial pipelines were valorized in the publications of the day. From the early days when mustangs were chased down by men on horseback to the more modern era of airborne hunts, “mustangers” were often presented as tough hombres who were taking on “demon” or “outlaw” horses -- renegade animals who were getting away with something simply because they were running free.

Things began to change in the 1950s when a Nevada secretary named Velma Johnston was driving to work one morning and spotted blood spilling out of a truck on a desert highway. She followed the truck to a remote location and watched as injured and dying mustangs were offloaded at a rendering plant, taken there by men whose stories were told in the iconic film, “The Misfits.” For the next 20 years, Johnston battled to stop these cruel roundups, which had plagued the west, and to bring about legislation to protect mustangs. Four bills were passed, in the county, state, and federal legislatures, and along the way Velma came to be known as “Wild Horse Annie.” Thanks to her, mustanging became illegal, and management of wild horses passed primarily to federal agencies. There are wild horses still running the range today -- although in ever-dwindling numbers as their herds are increasingly “zeroed out,” or eliminated.

Sadly, tax-funded overseers often engage in a modern version of yesteryear’s cruel practices (as I’ve written about here and here), and after the round-ups, horses fall into an Orwellian system of government housing, with many living out their lives in pastures on the prairie and others adopted out to a variety of individuals and outfits, from police departments and border patrol units, which do well by the horses, to citizens, kind and unkind. Some of these horses ultimately make their way to slaughterhouses, joining the legions of others who have reached the end of the trail.

When equine slaughterhouses were banned in 2007, the rendering of American horses did not stop. And this includes wild horses; while they cannot be purchased for slaughter, many fall through the cracks, and in fact, right now there is a federal investigation of just such a possibility as a result of this recent report. Moreover, mustangs that live outside of federal jurisdiction sometimes make their way into the pipelines, as in the auctions of state-owned wild horses in Nevada, which labels them as “estray” -- meaning “feral,” or disposable. In the past couple of years, mustang-minded private citizens have come forward and participated in these auctions, saving hundreds of horses from “kill buyers” as they are known. (Like Ellie Phipps Price of Dunstan Wines, who financed the purchase of 172 horses on death row and later placed them on land where they will live out their lives.)

The legions of horses that are purchased at auctions and elsewhere are now shipped across the borders to Mexico and Canada, often in trucks that are overcrowded, to an end that no animal deserves. The shipment of horses to foreign slaughterhouses is one argument used by those who want to reopen the plants in the United States. “Let’s keep it local,” they say, invoking a strange form of patriotism. “We have regulations, and things aren’t so bad.”

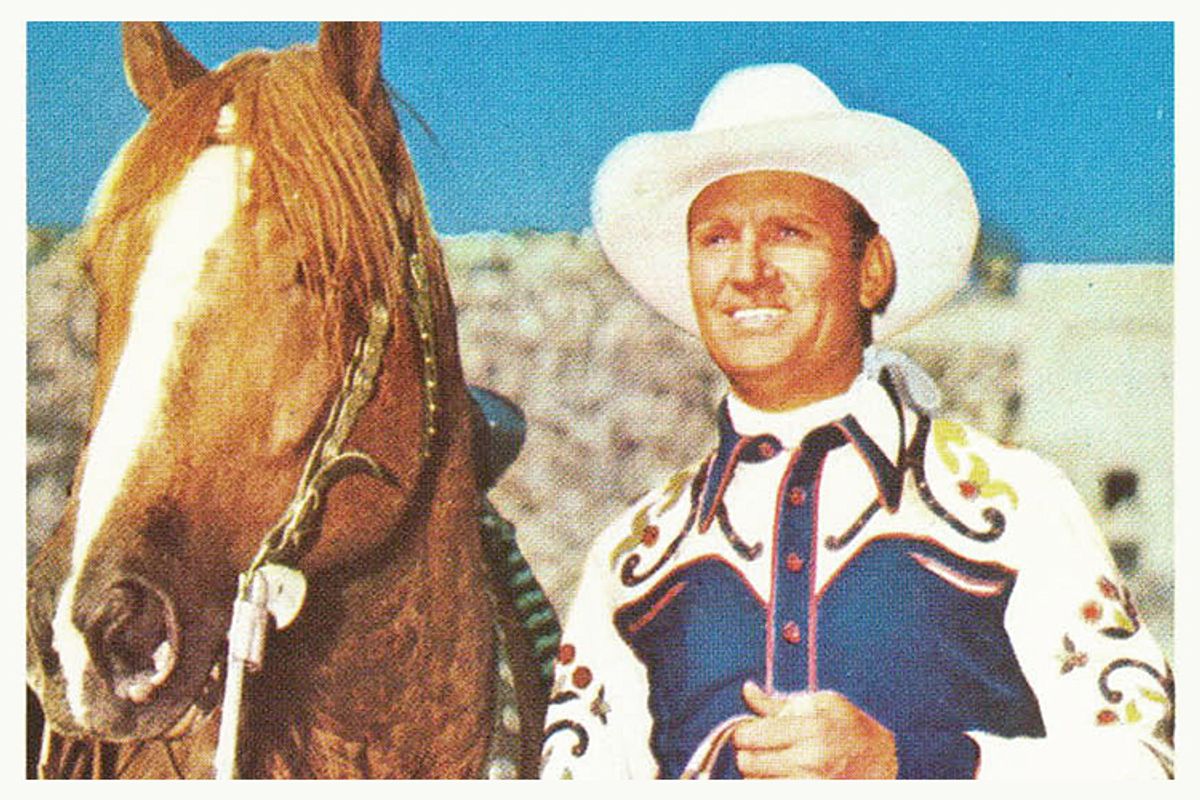

Of all states to get involved in a 21st-century culling of horses, it’s stunning that the first to sign on is Oklahoma. The Sooner State is associated with two of the country’s most revered cowboys -- Tom Mix and Gene Autry. Hollywood icons both, they were celebrated not just for their theatrical talents, but because of their partnership with the horse. In fact, both of them had horses -- in Autry’s case, a string of them -- that eclipsed their own fame, helping to build not just Tinseltown and its westerns but also making sure that American mythology lives forever.

Tom Mix was born in Pennsylvania and learned to ride from his father, a stable master. As the story goes, he fought in the Spanish-American war, in the Boer War and with the Texas Rangers against Pancho Villa. In the early 1900s, he moved to the Oklahoma Territory where he found employment with the Miller Brothers' "101 Ranch Real Wild West Show" and became a top performer. He was soon discovered by a Hollywood production company and made several movies, becoming quickly recognized by cowboy stuntmen and fans alike as the best horseman of them all.

Like Autry, his fame was surpassed by his horse’s -- Tony was the name, one in a series of Hollywood steeds labeled “Wonder Horse.” There are various stories about where Tony came from, but most say that he was discovered by Mix’s wife, Olivia, when she spotted him following a chicken cart that Tony’s mother was pulling on Glendale Boulevard near downtown Los Angeles. He was about two years old. Olivia contacted Mix’s trainer, who lived nearby. He liked the look of the sorrel with the long white blaze and white stockings on his hind legs and bought him for $14.

Over the next couple of years, the trainer taught Tony the tricks that would make him one of the country’s most beloved stars. He learned to respond to lines of dialogue and appeared to engage in conversation with Mix. The conversations made the pair wildly popular, and Tony became the first horse to receive equal billing with his rider. He was even included in a few movie titles -- “Just Tony,” “’Oh! You Tony” and “Tony Runs Wild.” At the height of his career, Tony was so well-known that he received mail addressed to “Just Tony, Somewhere in the USA,” visited the White House and appeared on Broadway, posing for his debut as he got a manicure and pedicure while photographers snapped away.

But like other Hollywood horses, Tony’s life was periodically endangered and sometimes he was hurt during the process of re-creating our founding legends. One time, Mix and Tony got too close to a dynamite blast and were thrown 50 feet. Mix was knocked unconscious and Tony suffered a serious cut. The accident didn’t impair the pair’s career. “Tony was very much like his owner,” one director said. “His trainer would rehearse him in some tricks and he would perform beautifully, but when it came time to shoot -- nothing! He could be whipped, pulled, jerked, have bits changed, but still no performance. Come out the next morning and he would run through the whole scene with barely a rehearsal. Then he’d look at you as much as to say, ‘How do you like that?’”

He toiled until 1932, when he was retired and replaced by Tony Jr. Strangely, in 1940 Mix’s own career was cut short in a freak accident on an Arizona highway while he was driving near his ranch in Florence. Ignoring warnings that a bridge was out, he drove into a gulley and was hit on the head by a suitcase that flew off the rear shelf in his roadster. Today, there’s a sculpture of a grieving horse at the site where Mix was killed on an Arizona highway near his ranch. On a plaque at the memorial, under the heading “TOM MIX,” it says: “Whose spirit left his body on this spot. And whose characterizations and portrayals in life served to better fix memories of the Old West in the minds of living men.” Today, people can have their photograph taken with a fiberglass Tony at the Tom Mix Museum in Dewey, Oklahoma.

Born in Texas, Autry moved to Oklahoma in his teenage years. He spent much time with horses, but his passion was music. He was steeped in the music of his church choir, and as a young boy he learned to strum a mail-order guitar. In 1924, he met Will Rogers while working in a telegraph office. The famous cowboy had come in to send a telegram, and heard Autry singing and playing the guitar. Rogers encouraged him to pursue a career as a musician, and Autry soon got a job at a Tulsa radio station. He quickly became known as Oklahoma’s Yodeling Cowboy, and he soon made his way to Hollywood. There he was teamed up with a horse named Champion, who was owned by Tom Mix, already a superstar in his own right. Champion had been used as a stand-in for one of Mix’s famous equine partners. He was a beautiful chestnut with four white stockings, a Tennessee walking horse about 15 hands high. A trainer taught him to play dead, outrun cars and trucks, kneel in prayer, nod his head yes, shake his head no and answer to Autry’s famous whistle.

For several decades, Autry and Champion -- and later other Champions -- galloped across the American plain in dozens of films. Autry was the first singing cowboy on the silver screen, becoming known perhaps most of all for a song that became our unofficial national anthem. This was “Back in the Saddle Again,” which he co-wrote and crooned. The lyrics extol an idyllic existence -- being “out where a friend is a friend,” under the stars, riding the range, with only a gun and your horse. Autry later went on to host a radio show, “Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch,” during which he introduced his famous Cowboy Ten Commandments as a way to pass on his legacy to his legions of young fans. Number four is “He must be gentle with children, the elderly and animals.”

If there is a problem with “excess” horses, we must look to the underlying reason, which is overbreeding. We breed more than we need and, like a lot of other things, we throw them away when they’re in the way or somehow aren’t earning their keep. As the slaughter discussion proceeds yet one more time, let us remember that most of the horses sold for slaughter every year are thoroughbreds and quarter horses, jettisoned after performing a lifetime of hard service. Wild horses join them when someone is trying to make a fast buck or decides after “trying one out for a while” that who needs the trouble?

And let us also remember exactly what a slaughterhouse looks like. Consider the account of someone who not long ago worked in one. This person was interviewed by investigators at a secret location, and the account was entered into the record of a meeting held by the Assembly Committee on Natural Resources, Agriculture, and Mining of the Nevada state legislature on Marcy 29, 1999. As recounted in “Mustang,” here is part of the testimony:

I saw a lot of terrible things. When the colts come in, they’re not worth anything because they’re so small. So they hit them in the head and throw them in the gut pile.

I used to go into the corrals at night to be with the mares. They were still trying to take care of their young, like in the wild. Some of them got tangled up in the fences.

The most difficult thing for me to talk about was the time a heard a big ruckus and I looked down and there was this black wild stallion that they were trying to get up in the chute. But he knew what was coming. He reared. He turned around and tried to crawl over the top of the other hoses to get back down the chute. And, of course, man is always stronger and he is always going to figure out a way to get the job done because we’re talking about a dollar bill here … So they got all the crew out there. And they used the electric prods to prod him up …

And finally the guy on the kill floor came up, running upstairs, laughing. And he says, “You know the son of a bitch just didn’t want to die. But we got him. He got loose on the kill floor and they had to get a rifle before they could finally take him down.”

Sometimes at my book talks over the past few years, some of the old mustangers hobble on in. When I’m finished and the others have left, they approach me in tears. They have not come in with others, mind you, but alone; they are cowboys after all, lone rangers, and they look haunted. Yet there are shreds of pride; they are standing tall, still handsome, craggy, weathered by years of toiling in the natural world. They tell me that they have looked across the land and they see that the things and places they loved are gone. They are sorry for their role in the decimation of our herds, our heritage, and they fear that our greatest partner is on the way out. What can they do, they ask, I just wish there was something I could do.

And they linger for a moment or two and I tell them that I’m not sure, thank you for coming and letting me know these things, just keep telling your stories. By then, my eyes are welling up, and it’s all too much and that’s generally the point at which they head on out the door, just like Shane in the movies.

Shares