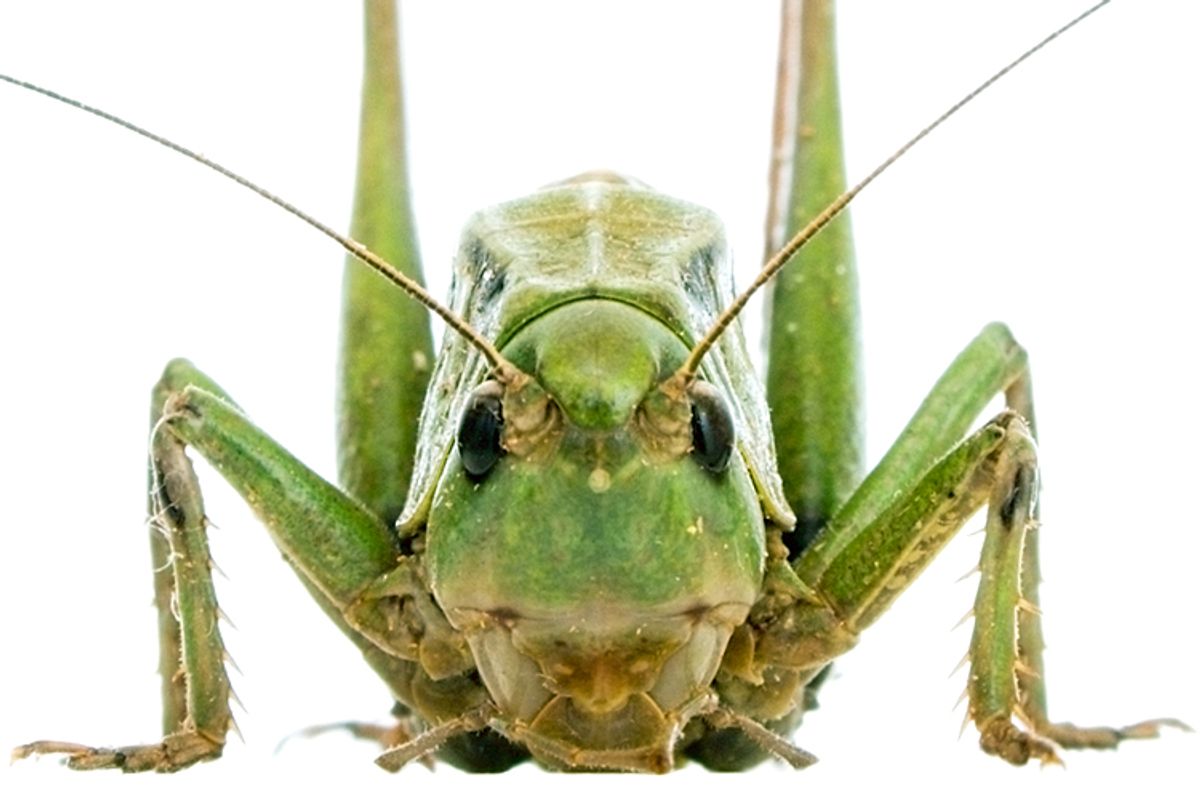

By the time my taco arrived, our party of five had settled in around a table by the window. We'd agreed on the tastiness of the chips and salsa, and put away a ceviche or two. We had talked shellfish allergies with Geoffrey, our server, and had marveled at the "salt air" topping off the restaurant's signature margaritas. When my taco arrived, though -- a fold of tortilla supported by something that reminded me of a napkin holder and cradling on a bed of guacamole dozens of sauteed grasshoppers -- my dinner companions fell silent. All eyes turned in my direction. The "serious deflowering" -- as Eric had termed the evening’s main event -- would soon occur.

No accident brought me to Oyamel Cocina Mexicana in Washington, D.C.’s Penn Quarter that Thursday night, or had me facing down chef Jose Andre's legendary chapulines. Nor did chance place a co-worker at my elbow or a pair of college friends across the table from me. No. Your first time, they say, should be special, and I wanted to take the plunge when and where I wished and in company both trusted and experienced.

Experienced, that is, in omnivorism.

I grew up in a vegetarian household where family dinners rotated through a stable of standbys: rice and beans, millet and mixed vegetables, pasta, baked potatoes. My dad became a vegetarian at a young age for health and ethical reasons, and my mom "converted" when she married him, never having cared for meat anyway. Though my parents decided to raise my sister and me vegetarian, they never forbade us from sampling our friends' chicken nuggets or meatballs or corn dogs. For decades, then, I attributed my steadfast avoidance of flesh ingestion to force of habit, to the smelliness of meat, its lack of color and crunch, the care that had to be taken in preparing and eating the stuff, riddled as it was with blood and bones and invisible vectors of food-borne wretchedness.

When I was a college junior, though, my vegetarianism got principles, and, as principled vegetarianism often does, transitioned swiftly into veganism. Prompted by the probing questions of a veg-curious friend, I read Peter Singer's “Animal Liberation.” I saw that to register disapproval of the factory farm atrocities Singer documented, I had to eschew eggs and milk products as well as chicken and beef. Within a month I had swapped skim milk for soy on my sometimes thrice-daily cereal and gained a new appreciation for the dining hall's occasional inclusion of Tofutti in the ice cream bar. I'd never liked eggs anyway or developed a taste for the Bries and Gruyeres that send cheese lovers swooning. Adhering to a vegan diet was easy for me, and whether I cared about my health, the environment or animal welfare, it was the right thing to do. I was certain.

There in the low-lit hum of a bustling Mexican restaurant, though, I regarded my boatload of grasshoppers with a look of anything but certainty. The night before, see, in a frenzy of 11th-hour background research, I had learned a thing or two about chapulines. Whether sautéed with tomatoes and jalapenos or toasted in a mixture of garlic and lime juice, the grasshoppers are something of a specialty in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. My dinner companions Eliza and Rachel both recalled eating chapulines in Oaxaca as children, buying the insects from a street vendor’s basket, snacking on them -- ground up beyond recognition -- from a bowl like so many cocktail peanuts.

Neither of my friends had experienced any ill effects after their youthful indulgence in Mexico’s insect delicacy, but as I read about possible lead contamination and the danger of undercooked grasshoppers passing their nematode parasites up the food chain to incautious human consumers, I worried I wouldn’t be so fortunate. And our server’s spiel about shellfish allergies only heightened my unease. Shrimp and grasshoppers are both arthropods, and it’s a polysaccharide -- chitin -- common to the exoskeletons of both that causes sensitive eaters to suffer indignities ranging from hives and congestion to dizziness and vomiting.

"But we don’t know whether she has shellfish allergies," Rachel told our server as I joked to David, my co-worker, that if I didn’t show up at the office in the morning, he’d have an inkling why.

Even as chapulines leapt to new highs on the scale of foods I suspected would make me sick, though, I could not deny that they ranked low on several other scales of concern to me. Talk of "lower animals" may have ceased once biologists stopped conceiving of life as strictly hierarchical, I’d been saying to David when Geoffrey arrived to take our drink orders, but on a likelihood-of-consciousness ladder insects had to be way down there. (Right?) I also pegged a grasshopper’s capacity for suffering as less than that of, say, a salmon or a chicken or a veal calf. I remembered Peter Singer conceding the possible ethics of eating oysters, based, as I recalled, on the seemingly slim chances of bivalve self-awareness.

My plan for meat ingestion, then, was to start with grasshoppers and, as conscience, palate and digestive system allowed, "work my way up." Up what exactly I left unspecified, though some scale of relatedness to humans seemed as good and concrete a candidate as any.

"What percentage of our genes do you think we share with grasshoppers?" I asked David as we waited for our appetizers to arrive.

"Seventeen," he said, after a pause.

Such estimates of genetic commonality -- the true figure is closer to 36 percent, I learned later -- crop up rarely, if ever, in arguments for incorporation of insects into the Western diet. Pleas have been increasingly widespread lately, with pieces in publications from the Wall Street Journal to Time to the New Yorker extolling the benefits of entomophagy, the intentional ingestion of insects. Advocates note the efficiency with which the likes of silkworms and cockroaches convert plant food to edible body mass, and cite the ease and relatively low environmental impact of farming waxworms or water beetles. Already a dietary staple in many parts of the world, insects could provide consumers in Europe and North America with a low-fat, eco-friendly source of protein. A sizable impediment, of course, is the so-called "ick" factor, the aversion we Westerners have to eating bugs.

Icky or not, my taco made no bones about brimming with bugs. Though thankfully smaller than the grasshoppers I’d encountered in the fields of Pennsylvania as a kid -- more what I think of as cricket size -- the chapulines had readily discernible legs and eyes. I tried not to calculate the total number of appendages. I suppressed the thought that once I multiplied the low individual capacity for suffering by the scores of insects that had died to make my taco, ingestion of the thing would probably prove more ethically suspect than I’d realized.

Eliza already had a camera phone pointing at me, though, so I raised the taco to my mouth, took a bite, and chewed. No anaphylaxis. No legs stuck between my teeth. Just the creaminess of avocado, the tang of tequila. And a crackle now and again -- testament to all those chitinous exoskeletons.

"You can’t call yourself a vegan anymore," someone said.

I shrugged. It wasn’t like I habitually introduced myself "Hi. I’m Katharine, and I’m a vegan." I was never in-your-face about my food choices. I would gladly outline the rationale for a plant-based diet if questioned, but I didn’t proselytize. And I found many vegans off-putting in their adherence to the letter rather than the spirit of their self-imposed food rules. Was hunting really so horrible? I wondered. How could anyone be so smugly certain that a highly processed amalgamation of soy, wheat and pea protein carried with it a lesser moral price tag than an omelet made from eggs sourced from a family farm you had visited to personally verify the well-being of the laying hens?

I had initiated the visit to Oyamel under the influence of those entomophagy articles, yes, but also because of a growing conviction that the best diets probably defy easy characterization. Rather than ruling out whole classes of comestibles, I decided, I’d evaluate individual meals and ingredients on their own merits -- healthfulness, ethicality, taste, cost, environmental impact -- and determine from there what to cook, what to eat, what to order. I’d have to think about my food more this way, be more willing to research options and question waitstaff. But then our society, plagued by ills brought on by heedless, uninformed gobbling, could use an uptick in mindful eating.

Early in the evening, Eliza had forked onto my plate a tiny cube of raw tuna. For later, she explained. In case the chapulines didn’t max out my adventurousness. After that, with each tapas-style dish Geoffrey delivered to our table, the variety of particulate pieces of flesh arrayed in front of me expanded. David contributed wahoo, Rachel tamale. It was corn mostly, but had a bit of chicken inside. And when David’s tongue taco arrived, strips of braised muscle lolling out of it, I agreed that if he put a morsel of the mammal meat on my plate, I might eventually have the guts to face it.

I ate it all, in the end, and a sliver of stringy short ribs, too, before we called it a night. I still don’t cook meat or eat it regularly or in normal portion sizes. I still think it smells. But I’ve tried the stuff now, and I grant that it might, in moderation, have a place in a healthful, morally defensible diet.

Maybe I’ll brave an oyster fest next.

Shares