“Ayeeeeeeeeeeee.”

Inside the tent, Patrice Wojciechowski, one of the company trapeze flyers, watched a little girl zip above him. She streaked through the dome’s open expanse, arms and legs churning the air. Cast against the tent’s luminescent black interior, she looked like a pale spider swinging by its thread.

“They’ve been doing this all day,” Patrice said. He kept his blue eyes pinned on the girl. “We call it the pendulum. On most days we don’t let the kids near it, or any of the rigging. But, you know, it’s a special night.”

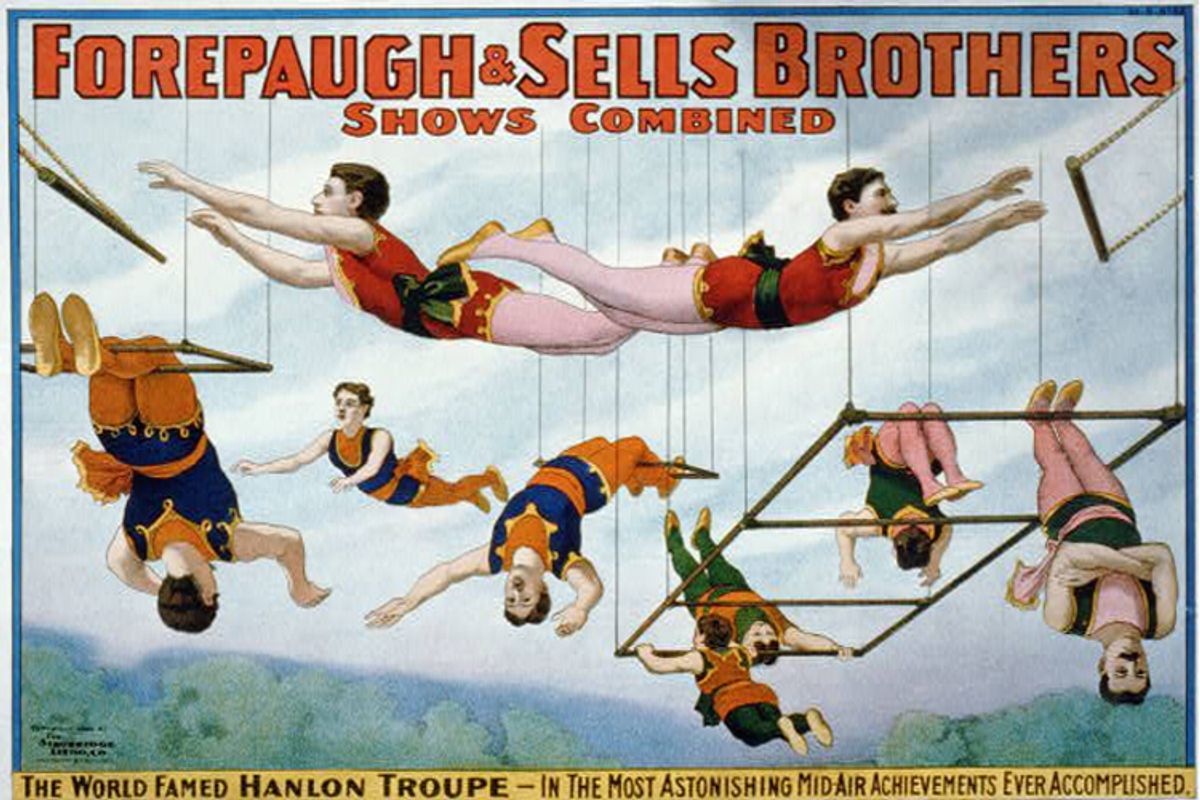

It’s been said that flyers are the “aristocracy of the circus,” and there’s some truth to this. There’s unquestionably something elegant, even graceful about the way they drift and plummet. Like the higher rungs of society, flyers are also uniquely distinguished, both within the circus and without. Gossard likes to call them “the greatest performing athletes in history.” “Of all the great athletes, how many would have the courage to even climb a rope ladder?” he told me. “Of those that do, how many have the ability to swing off? How many have the timing to make a hand-catch? How many have the personal ability to do any kind of trick? That’s a really unique person who can pull that off, one in millions.”

There’s also something dynastic about the history of the craft. Since the beginning, a rotating roster of nations have produced the discipline’s greatest stars. First came the French, then the British; in 1897, Lew Jordan, an American, discovered and trained Lena Jordan to throw the world’s first triple somersault. Other triple somersaults followed: Ernie Clarke in 1909; Ernie Lane in 1921. There was a hub for American aerial royalty in Bloomington, Illinois, and another in Saginaw, Michigan. Neither city seems especially regal, but they were milling towns and so produced sawdust, whole barns of it, which was useful in an age before nets.

Since then, the reign has shifted several times: to the South Africans, the North Koreans, and especially the Mexicans, who are power specialists. Their technical feats are astounding. Tito Gaona estimates that he had thrown more than twenty thousand triples by the age of forty-three, including several dozen blindfolded. He tried to become the first flyer to throw a quadruple, but never managed it in performance. Instead, the honor went to Miguel Vasquez, who, as a sixteen-year-old, first threw a quadruple somersault to his brother during a practice for Ringling in August 1981, and then during a performance in Tucson the following July. (News of the stunt was featured on the front page of the New York Times.)

In the history of flyers, however, one Mexican stands out: Alfredo Codona (he of the cracked ribs). Born in Hermosillo, Sonora, in 1893, he was the son of a circus manager and a former flyer. After starting as a solo trapezist for Barnum & Bailey in 1909, he switched to the flying trapeze in 1913, recruited by his father for an act with his brother, Lalo.

Technically, Codona was top-shelf: he was one of the first flyers in history to throw a triple consistently, a stunt he learned without the use of a safety belt. His fame, however, was also due to his grace. “He couldn’t look bad,” Art Concello, another flyer, once said. “If Alfredo had been run over by a truck, he’d have done it so gracefully that your first instinct might have been to applaud.”

I was hoping to talk to Patrice about some of the great flyers; jugglers loved to chat about the old masters, from Brunn to Rastelli. But Patrice was distracted. Melancholy tinged his voice. His answers meandered. When I asked him about the joy of flying, he talked about work. “People compare us to birds,” he said, watching another child get buckled into the pendulum above us. “Unfortunately, we’re not birds. A bird flaps its wings — flap, flap — and up he goes. For us, it’s incredibly hard.”

After a few minutes, the problem dawned on me: I had interrupted Patrice’s pre-show routine. The clowns of Cirque d’Hiver were notorious for drinking until showtime, then sprinting back to the bar during intermission, but few acrobats are so cavalier. They take this time seriously. (The backstages of Cirque du Soleil, I’m told, can be as tense as the locker room of a professional football team before a playoff game.)

I reflected on this in silence next to Patrice, watching the kids whiz by above. For all my dabbling — all the books, conversations, and classes — here was something I would never comprehend: how it must feel to be a circus performer, to experience the pressure and the pleasure of executing a dangerous feat with hundreds of people watching, to gaze down on all those faces, grip the bar, and swing.

*

The following Friday, I returned to the Great Hall for my reintroduction to the flying trapeze. As I arrived, another student, an obvious amateur, was breezing through her final flight — swinging out, her knees draped over the bar, ejecting into the arms of a stocky catcher in leopard-print leggings. I felt my heart pound. I had been hoping the conversations with Les Arts Sauts would have worked some osmotic magic on me. Clearly, this wasn’t the case.

“Who’s next?”

Stripping off a pair of work gloves, a coach came striding toward me under the net. He was in his forties, with tousled blond hair, an unseasonable orange pallor, and the saunter of a cowboy president. When we shook hands, I could feel the calluses on his palms, stiff sheets on top of muscle. He introduced himself as François, but said that everybody called him Tiger. Later, I would find that his type was common among flyers. As Laurence said, they tend toward casual cool.

Tiger briefed me on the trapeze. When he asked me about my previous experience, I told him I was a rookie, not feeling the need to rehash unpleasant memories, and this seemed to please him. Grunting in a satisfied way, he clapped me on the shoulder and said, “All right!” And then, “Don’t worry, we’ll make sure you won’t die! You’re gonna live!” Which I appreciated.

We walked to a box of harnesses. In circus lingo, the rigging acrobats use to train or as a security precaution during performances is called a "safety belt." (Codona referred to the device as the “life belt of the circus.”) Safety belts, surprisingly, are the object of some controversy among circus professionals. The pro-belt camp points, of course, to the increased safety that belts bring, and also to their effectiveness in training: learning with a belt allows an acrobat to focus on technique without thinking about danger. Those against belts claim the devices interrupt the learning process by providing a false crutch and detract from how acts look in performance. They also lower the appeal: wearing a belt for a high-wire walk, they say, is false, dramatic, and sometimes just unimpressive, like putting a helmet on before banging yourself in the head with hammer.

“You want some help with that?” said the catcher in the leopard leggings, ambling over to where I stood holding the harness. We chatted as he set to work untangling the mess I had made trying to put it on. His name was Claude, and he was actually an amateur himself. Five years ago, he told me, he had discovered the discipline at Club Med. This was not uncommon. In the eighties, as other circus arts were catching on as recreational pursuits, Club Med had the brilliant idea of slipping the trapeze into their usual resort smorgasbord.

Claude handed me the harness, and I wiggled into it as if it were a diaper. He cinched the buckles on my hips and took a step back, looking at me as if fitting me for a pair of trousers.

“How’s that feel?”

I did a couple of deep knee-bends. “It kind of pinches.”

He nodded. “That means it’s tight enough.”

I waddled after Claude to the base of the ladder, which resembled a series of metal chopsticks strung between two wire fishing lines. He reiterated the correct climbing procedure: use your heels, one rung at a time, alternating feet — like climbing a rope. I was barely two meters up before the adrenaline rushed in. The room swooned. Details became crystal clear — the shine of the metal rungs, the sweat on my palms, the sharp wires bumping my crotch. Below there was only a single mat. Its width and thickness struck me as laughably inadequate to the task of saving a life.

I groped my way toward the feet of the women on the platform, then lunged at them. “Wow,” came a voice from above. “Very brave!”

Meet Claudette. In the argot of the biz, Claudette was my “board muffin,” the assistant who helps the flyer find his way safely off the perch, as well as prepping trapezes and securing the lines. Usually board muffins are experienced flyers themselves, and this was obviously the case with Claudette: her shoulders bulged, and her torso cut the telltale V.

“So,” she said, once I’d hauled myself to my feet and established a white-knuckled grip on one of the bars running up to the ceiling. “I take it this is your first time?”

I inhaled a pungent odor, a mix of chalk and sweat, and nodded in reply.

Claudette laughed. “I’m jealous!” And she set to fastening me into the ropes, handling me like a rag doll, jostling against my back, making the perch sway unnervingly. Trying to maintain focus, I leveled my gaze out over the net. The mécanique might be a subject of debate, but the net was universally agreed upon. Everybody, from Cirque du Soleil to impoverished trapezists in the most reckless circuses of Brazil, flies with nets.

This hadn’t always been the case. As with much of circus history, the exact origins of the device are murky. According to legend, a pair of American flyers, Charles Noble and Fred Milmore, saw a group of fishermen hauling a catch out of the Illinois River and had a flash of insight. But their net was slow to catch on. Theater directors balked at the cost of installation. Flyers worried about the loss of excitement. “With the net, where’s the thrill?” Louisa Cristiani, an Italian flyer, once quipped (before shattering her spine and four ribs at Madison Square Garden). But in the twenties, Parisian music halls moved to ban “flying open,” and the city followed suit. (This wasn’t the first such law. In ancient Rome, Marcus Aurelius mandated safety mattresses after a tightrope walker fell to his death.) It was an enormously important step, but, as flyers like to point out, nets aren’t marshmallows. They are rope — rigid, taut, prickly rope. It won’t hurt you if you land correctly — on your butt or your back — but this isn’t always possible, and so nets regularly snap wrists, legs, even necks. Codona, a man comfortable in a net if there ever was one, once called the device a “lurking enemy.” The knots, he noted, possess a “satanic joy in gouging the flesh.”

I happened to read these lines two days before my trip to the work- shop. I gazed out over my own “lurking enemy” with the words echoing in my head — “satanic joy in gouging the flesh” — and was grateful to hear Claudette’s carabiner click behind me, alerting me that I was officially locked in.

“So.” Claudette’s shining eyes emerged around my hip. “What are you doing?”

The question struck me as a riddle. I told her I was waiting for her to finish whatever she was doing.

Her eyes narrowed. “I mean, what trick?”

In fact, Tiger had decided that I should begin with a knee-hang. I related this to Claudette and in the process realized what I was about to attempt — hanging from my knees upside down — and immediately felt another jolt of adrenaline rip through me. Meanwhile, Claudette explained the move: At Tiger’s command (“Hep!”) I would spring from the board and swing, hanging below the trapeze, until I heard his next command (“Legs up!”), at which point I would heave my legs up to my chest, pass them through my arms, and drape them back over the bar. In this tucked, inverted position, I would then swing until Tiger yelled, “Hands off!” whereupon I would let go of the bar and dangle from my knees.

While Claudette was describing this, I rehearsed the move in my head. Most acrobats, like most athletes, have gimmicks they employ to steel themselves. Christine Van Loo, a professional acrobat and former gymnastics champion, told me that as a girl she used to imagine Mikhail Baryshnikov in the room with her. “If I was really scared of something, I would imagine he was in the room watching me, and everything would be fine.” Tumbling, I had learned to visualize tricks in my head while executing a series of gestures: rotating my wrists, cracking my fingers, pointing each toe. In an interview with Marc Moreigne for the book "Avant-Garde Cirque," one of the flyers for Les Arts Sauts claimed to use chalk for a similar purpose, to create “a space of calm before the moment of action.” With this in mind, I dug out a handful of chalk from the bag attached to the pole and slathered it on my palms and my wrists. I didn’t feel any stillness or clarity, only a small moment of feeling manly.

“Think you’ve got enough there?”

I looked up. Claudette was gazing at my arms bemusedly. They appeared to have been dipped in flour. I had also managed to get chalk on the backs of my knees and kneecaps. The manly feeling lessened before dissipating completely as Claudette drew the trapeze bar toward me with a long hooked spear (a “noodle”) and told me to take it with my left hand. I hesitated. Claudette repeated herself slowly: “Take ... the ... bar ...” I followed her instructions.

Watching Les Arts Sauts, I’d assumed the bar was made of wood, but in fact it was quite heavy, made of metal wrapped in grip tape, and now, thanks to me, covered in chalk. I felt the weight of the bar pulling me out into the void, and at the same time noticed that Claudette had at some point taken hold of my harness and was tugging me backward by the diaper.

“Take the bar with your second hand.”

This seemed like an impossible command. I was sure I would tumble forward.

“Take ... the ... bar ...”

I took the bar. Magically, my position held, thanks to Claudette, who was now leaning backward.

For a moment, Tiger futzed with his gloves. We waited, a tableau of anticipation. It was easily the most emasculating moment of the year thus far: watching my arms wobble while a woman whom I knew to be of significantly greater fitness than myself kept me from plunging to my death by giving me an aggressive wedgie.

“Got it!” Tiger’s voice rang out, his vexing glove issue resolved. He reached up and took hold of the ropes.

I felt Claudette increase the pressure on my wedgie. Voices became inchoate. Tiger yelled something. Claudette yelled something. Again Tiger’s voice:

“Hep!”

I jumped. As I rushed downward, the wind pushing against my body, gravity pulling me toward the ground, the adrenaline flooded in. Again, I became hyperconscious of certain minute details — the pull of the bar on my armpits, the rough, stringy texture of the grip tape in my palms — and not at all of others. There was no sound, not even my breathing. It was as if I was underwater. Just a vast cloud of silence, occasionally shot through with voices.

“Knees up!” Tiger bellowed from below. I had arrived at the far side of the swing. I tried to heave my knees toward my chest, but gravity prevented it. I felt my stomach muscles clench.

“KNEES UP! KNEES UP!”

I hauled my knees toward my chest. My feet wouldn’t fit under the bar. I clawed at it with my toes. Get through! Get through!

They broke through. I pulled my thighs against my chest and draped my knees over the trapeze so that I was tucked into a ball, the steel of the bar in the soft crevice of my calves, my hands gripped on the bar, my thighs tight against my chest.

“The bar!” Tiger shouted. “The bar!”

My mind raced. The bar? What bar? I felt a half-second behind every move.

By now my swing had brought me back to the perch. I saw it and momentarily considered grabbing it.

“Not that bar!” Tiger screamed. “Your bar! Let go of your bar!”

I did.

Later, when we were settled on the ground after the flight, laughing about the warbling sound I had made upside down, about the way I had uncontrollably waved my arms and clawed nonsensically for the ground, I asked Tiger how he would describe his first flight on the trapeze, what he would compare it to.

Immediately the laughter died down. Tiger shook his head with gravitas. “No, man,” he mumbled. “There’s nothing like it, nothing like it in the world.” And Claude added: “Except maybe an orgasm!”

All told, I made seven flights that day. The experience of each was roughly identical to the first. Climbing the ladder, I would get fired up. On the perch, Claudette would give me feedback about the previous flight. In one instance, she pointed out that I was unconsciously tensing my arms, leaving me less room to push my legs through. “Just let them go loose,” she coached, extending a pair of limp arms in front of her. “You don’t want any unnecessary tension.” Each time, I tried desperately to focus on her words before hurling myself again into the void and immediately forgetting them all. This was normal, I was told.

Afterward, with my hands still raw from the bar and my muscles still charged, the memory of the rush was very strong: the chemicals of peril charging through you, the swish of your body racing through the air, the feeling of gravity seizing at your arms. The activity was more physically challenging than I remembered, more extreme and difficult than the exercises at school. The next morning, I awoke to find every muscle in my torso was sore.

Oddly, though, it hadn’t felt like exercise, not in the way tumbling could. I was too much in the moment to notice the effort, too distracted by the rush. It reminded me of a full-body sport like rock-climbing or skiing. There was no heaviness to it, no sense of purposely expending force or power, as in many other acrobatic activities. What I actually felt was a tremendous sense of lightness. I didn’t really appreciate this right away; I had to burrow through layers of fear and learn to work with the forces of motion. But once I did, there was a feeling of covering a lot of ground quickly. In an age of increased awareness and creative engagement with the body (yoga, break-dancing, Zumba, and all the rest), it was a near-perfect workout.

Over the next two months, I went back every Friday for more of the same. I would love to say I made huge strides, but this was not the case — once a week wasn’t enough for mastery. I did see some small improvements, though. I learned the correct swing, which was surprisingly complex and involved pumping your legs to an odd rhythm and holding a pike position on the backswing — hell on the abdominals. I mastered the knee-hang and tried a few swings without a harness, a breathtaking experience, and even threw a few moves to a catcher.

The first time didn’t go well. From a knee-hang, I was supposed to arch backward with my arms extended, such that Claude, also hanging by his knees, could reach out, grab my wrists, and drag me from the fly bar. Unfortunately, on seeing Claude in my peripheral vision, dangling upside down, my head full of blood, my instinct was to lunge for him aggressively, the way you would reach for a branch if you were falling through a tree. That not only ruined the rhythm, but actually made the transfer more difficult, since Claude had no idea where I would be. (“Don’t grab him. He’ll grab you.”)

We tried the move twice. Both times I made the same mistake, and after each received the appropriate dressing down from Tiger. (“Just don’t do anything! Just put your freaking arms out!”) Finally, on the third attempt, we connected. Claude’s printed leopard tights rushed toward me. I extended my arms. I was sure the move wouldn’t work, but at the last instant, I felt his wrists smack mine. Then I felt the hard fly bar pull away from my knees. Suddenly I was rushing forward as if on a zip line, my hands locked into Claude’s.

The accomplishment of the feat provided two notable lessons. The catch itself was thrilling. I experienced a euphoria unlike anything I had felt in other disciplines — the rush of being airborne, even for a moment. But there was also the pleasure of accomplishment in the slap of Claude’s arms against my own. It was a big achievement.

Excerpted from "The Ordinary Acrobat" by Duncan Wall. Copyright © 2013 by Duncan Wall. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Shares