Nuclear war is unthinkable. At least, that’s what we like to tell ourselves. Given the mass death and devastation from an atomic strike, surely only a desperate despot would even consider such a strike.

Nuclear war is unthinkable. At least, that’s what we like to tell ourselves. Given the mass death and devastation from an atomic strike, surely only a desperate despot would even consider such a strike.

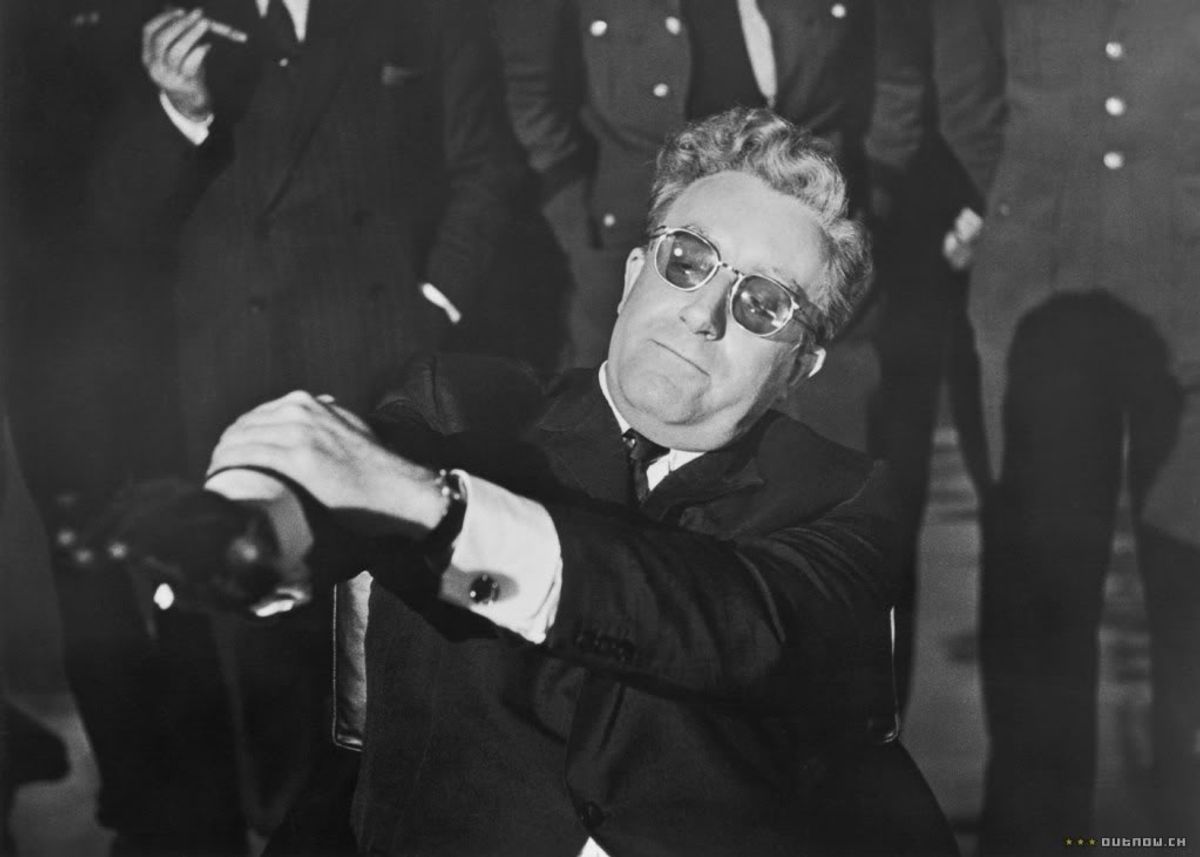

Slim Pickens joyfully rides a nuclear bomb onto a Russian target in the classic satire, “Dr. Strangelove.”

Well, think again. A new study finds that, among the American public, the taboo against the use of nukes is far weaker than you might imagine.

“When people are faced with scenarios they consider high-stakes, they end up supporting—or even preferring—actions that initially seem hard to imagine,” said Daryl Press, an associate professor at the Dartmouth College Department of Government.

Give the right set of circumstances, those actions include a nuclear strike—even one that results in huge loss of life. That’s the central finding of a paper that Press co-authored with Scott Sagan and Benjamin Valentino, published in the American Political Science Review.

“We initially set up the study assuming there would be a strong aversion to using nuclear weapons,” he said in an interview. “The design was created to determine how strong an incentive to use (nukes) do we have to create before people reluctantly sign on. How much of a military advantage would the nuclear option have to give above the conventional option before people would say, ‘We have to do this’?

“We found you barely have to put a finger on the scale.”

Press and his colleagues conducted a set of experiments with the help of Internet polling firm YouGov/Polimetrix. For the study, YouGov created five sample groups, of about 150 people each, to represent the American public.

In one experiment, participants read a fake news story about an Islamic terrorist group which had gotten its hands on a small number of stolen Russian nuclear weapons. They were asked whether they would support an American attack to wipe out their base (which was in Syria), and if so, whether they would approve the use of nuclear weapons in that effort.

One group was told that both the nuclear and conventional attacks would have a 90 percent chance of accomplishing their mission. Another was told the nuclear attack had a 90 percent chance of success, while a conventional attack had a 70 percent chance. The third was informed that the nuclear attack had a much better chance of success: 90 percent, compared to 45 percent for the attempt using conventional weapons.

“What we found is that, if we told the respondents that a conventional and a nuclear strike would be equally effective—you’d have the same chance of destroying the target—people preferred the conventional option by roughly 4 to 1,” Press reported.

“But if we provided even a slight advantage to the nuclear option, the numbers flipped. At least half of the American public would support the use of nuclear weapons.”

Specifically, in the second scenario (where nukes provided a relatively slight advantage), 51.4 percent said they were in favor of using them. For the third scenario, where they provided a big advantage, that number went up to 68.6 percent.

The researchers also asked if participants would support a nuclear attack if they only learned about it after it happened (which is, after all, the most likely scenario). Nearly 48 percent said they would even in the first scenario, in which nuclear weapons’ success was comparable to conventional weapons. That number increased to 55.7 and 77.2 percent respectively in the second and third scenarios.

In another experiment, participants were presented with the same scenario. They were told the nuclear attacks was twice as likely to destroy the terrorist lab as an attack using conventional weapons, but that 25,000 Syrian civilians likely would die, compared to 100 dead in the conventional attack.

Thirty-nine percent still preferred the nuclear option, in spite of the enormous loss of life. (Remember, the Syrians are innocent bystanders here.) What’s more, 52 percent said they would approve of the assault when learning of it after the fact.

“That surprised me,” Press said. “I thought the resistance to using nuclear weapons would be much stronger. But in retrospect, perhaps I shouldn’t have been so surprised.”

While this study measures public sentiment rather than that of actual policymakers, he noted, history suggests that “acts that political leaders find inconceivable during peacetime become quite conceivable—and even attractive—in times of crisis.”

“In the years leading up to World War II, the U.S. opposed the practice of bombing civilians,” he noted. “The Roosevelt administration issued some moving speeches about the horrors of the German bombing of London and the Japanese bombing of China. It made the case that those acts were some of the clearest demonstrations that the Axis powers were on the side of evil.

“Then Pearl Harbor happened. In the blink of an eye, the U.S. went from a strong opponent of counter-civilian bombing to the greatest practitioner that ever existed. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were just the final period on the sentence. The U.S. literally burned down 64 of the 66 biggest cities in Japan, using incendiary weapons. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were 65 and 66.

“We think of ourselves as being different people, ethically, than our grandparents and great-grandparents who supported the destruction of Hamburg and Dresden and Tokyo during World War II,” Press added. “But the data suggests that, when push comes to shove and the stakes are high, we—like those who came before us—are willing to countenance and support even devastating military actions.”

Consider how U.S. attitudes toward torture changed after the 9/11 attacks. “If you and I had said in the year 2000, ‘Aren’t there circumstances in which America might want to torture its enemies?’, we would have been shouted down,” he said. “But in the weeks and months after 9/11, when people were afraid, it became a valid and acceptable view to hold.”

Press argues that if the public is of two minds regarding nuclear arms, it may reflect of the confused rhetoric of the policy elite. He notes there is a disconnect between how our political leaders talk about such weapons, and the assurances that we continue to give our allies around the world.

“Our two messages about nuclear weapons are: (1) These are terrible weapons, relics of another era, and we’re doing everything we can to get rid of them. (2) Don’t worry, South Korea: We have your back. If anyone threatens you with nuclear weapons, you can rely upon the U.S. nuclear deterrent.

“There’s a fundamental contradiction between those two positions,” Press said—something the South Koreans have already noted. Some in that nation are arguing it should develop its own nuclear weapons, just in case the Americans prove unreliable.

Choosing whether or not to use nuclear weapons, on the Korean Peninsula or anywhere else, would weigh heavily on any president. But this research suggests that, when faced with such a horrible decision, he (or she) needn’t feel constrained by moral queasiness on the part of the public.

If Americans believe they face a real and imminent threat, a nuclear strike by our forces is very much on the table.

Shares