The concept of Generation X is real. It’s not a false grouping imposed from the top. We can argue about the name. Many in my generation hate the name and that’s fair; it’s not a great name, but we’re stuck with it. However, some of that hate is wrapped up in hating the presence of a name and the attempt to explain who we are in a pithy way, so no matter what name we had, it would be hated. Even if we had a different name, the touchstones would still be there, and that’s what shapes us. It’s indisputable that there’s a large group of Americans who are molded by the cultural, political, economic and sociological things that happened in the 1970s and 1980s and as the result of being the small, apathetic generation that followed a large, optimistic generation that attempted to revolutionize America. Denying that is futile. And Gen X Americans have lived within a negative political climate our whole lives, causing widespread alienation, disaffection and apathy. This, against a backdrop of events like the rise of a mysterious sexual plague and a powerful drug ruining society and harbingers of the end of American global dominance: All of that had the feel of the beginning of the end of days. So, it makes sense that the first Prince song to capture a giant audience and become his first monster hit was a song about apathy and apocalypse.

The oldest Gen Xers were in high school when Prince arrived on the national scene with his fifth album and a single that spoke of the funkiest armageddon scene you’ve ever heard of: 1999. It was a perfect Gen X dance song built on the idea that the world’s about to end so, to hell with it, let’s dance. It came out in 1982, two years into Ronald Reagan’s first term, when the Cold War had reached a fever pitch and we seemed closer than ever to the brink of nuclear war. We had less faith in government and authority than any generation before us, which just deepened our sense that politics was meaningless fools’ play. Who, in this climate, could respect authority? Surely, the people running the world were moronic if they were inching us to the brink of mutually assured destruction. In the face of that, the optimism of the 1960s seemed downright Pollyannaish. This was not something we could march to change. This was something from which we could do nothing but unplug. Given all that, “1999” fit perfectly.

In this song, the apocalypse has arrived — bombs are overhead, the sky is all purple and people are running for their lives. Our nuclear nightmares are fully realized. Then Prince and his bandmates sing, “Tried to run from my destruction./ You know I didn’t even care.” What a seminal line for Gen X. The end is near. What are we going to do? Dance. And shrug. And have an ecstatic party. Because we’re smart enough to be apathetic; we know we can’t change this. We can ask painful questions like, “Mommy? Why does everybody have the bomb?” But, instead of imbuing the song with a sense of hope or resistance, it’s resigned to its fate. We never thought we had a chance anyway. “Life is just a party,” Prince sings, “and parties weren’t meant to last,” so it figures that this would happen. “Everybody’s got a bomb./ Could all die any day.” How cynical. There’s not a slacker ethos at play: Prince proposes we do something; it's just that something has nothing to do with political protest. We should party. It’s more of a spiritual protest that involves turning our back on politics. Society is falling apart, war is all around us, the leaders are power mad and myopic, war is imminent, the sky is turning ominous colors, and in Prince’s world, in their last moments before the end, people are dancing. It’s entropy, set to a funky beat.

Prince played with apocalyptic rhetoric, in part, because in the early 1980s the apocalypse truly seemed to be around the corner all the time. Whenever Prince cast his reporter’s eye out his window, he saw a world crumbling and about to end. “America” is the name of the fourth and last single from "Around the World in a Day" and, crucially, it's the first song on the album’s second side. (It was released at a time when cassettes and vinyl still mattered, which meant sequencing was still important.) “America” gives us an entirely different vision of the world than the utopian one Prince laid out in the album’s title song. The song is a sardonic reimagining of the patriotic classic “America the Beautiful,” which opens with what sounds like the record itself struggling to get started, as if it were an old car or a lawn mower starting, dying, then starting again, which anticipates the world of troubles in America that’s about to be described. Even the song itself isn’t working properly and is having trouble getting going. Once the song launches, we get Prince’s electric guitar playing “America the Beautiful” in lower, darker notes than the original. It signals the critique implicit in the song because that old familiar melody is now dripping with irony, like a sonic version of the American flag repainted in black and white, the colors bleeding downward in a messy way. Where “1999” proposed an apathetic solution to the problem of the oncoming apocalypse — dance! — in “America” Prince sees dystopia, and he offers nothing but what he sees. No solutions, no Boomerish optimism; he’s just a camera. He sees an America in deep economic trouble, living in fear of communist Russia and fighting a losing battle against educational apathy and youthful drug abuse. There are aristocrats, America’s upper class, climbing the corporate ladder, and there’s a poor young woman dying in a one-room cage fit for a monkey, and then there’s Jimmy Nothing. His name tells you how far he’ll get in life. In the chorus, Prince sings, “Keep the children free,” but it seems like that’ll be hard to do in this world.

All this is not nearly as bleak as the world Prince paints two years later in the title song and first single from "Sign 'O' the Times." It’s a bluesy plaint, a heart-rending portrait of a world dragged down by AIDS, gangs, crack, gun violence, the space-shuttle disaster and the overwhelmingly long shadow of nuclear war. Again, there are no solutions in sight. The chorus is just Prince simply saying “time,” almost saying the world is in so bad a state that it’s got him all but speechless. He concludes, a bit surprisingly, that he’s still willing to fall in love, get married and have a baby, so he’s not totally nihilistic; he hasn’t given up on life, but he doesn’t see anything to hope for. Yet, to an audience of Gen Xers who see the world his way and are apathetic, disengaged, hopeless and cynical, Prince’s worldview fits and lets them know they can trust him. He knows what’s goin’ on.

Prince’s relationship to Gen X is influenced by his being a Late Boomer; a different breed than their older counterparts. Late Boomers are aware of the dream of the 1960s, but they are also shaped by the failures and death of that dream, by the way that the 1960s did not change the world completely and by the spirit-crushing disappointments of the 1970s. Just like Gen X, Late Boomers are shaped by the reasons why the optimism of the 1960s turns into the apathy and entropy of the 1980s.

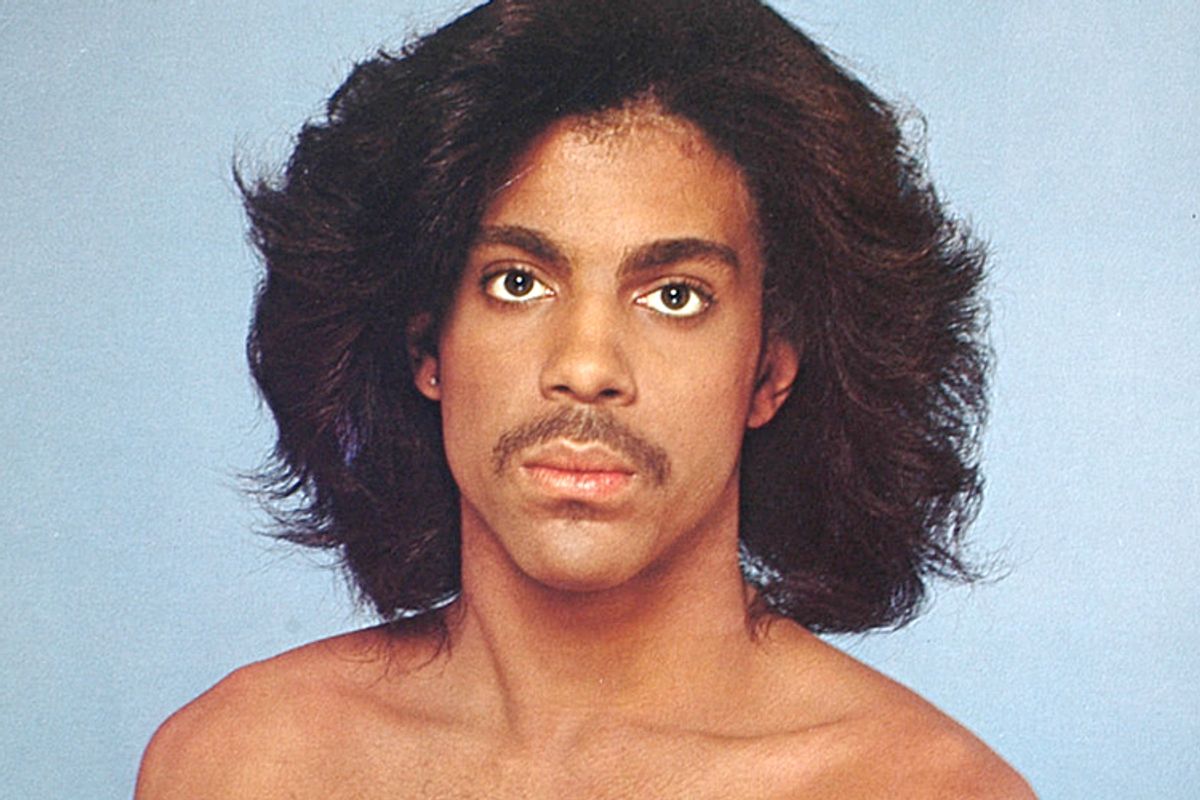

Some call the last half of the Baby Boomers “Generation Jones” because its members were too young to have been shaped by the Utopianism of the 1960s and too young to have experienced Woodstock. Generation Jones' members tend to be less optimistic and more cynical than Boomers; they’re trending toward the emotions that will mark Gen X. This is another way Prince’s space in the Boomer generation prepares him to speak to Gen X. But Late Boomers are still Boomers, which is why Prince’s sound and look immediately recalls many Boomer icons and why his music gave us some 1960s ideals. He looked and sounded like Hendrix or Santana standing in front of Sly’s band, and he danced in heeled boots in a James Brownish way while playing music clearly inspired by Brown, Joni Mitchell, Curtis Mayfield, the Beatles and the Stones. Prince has an unbridled and unironic love of the sixties, so when he goes to pay homage to the decade with "Around the World in a Day," he summons the psychedelic era of the Beatles, especially "Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band," the zenith of the decade’s ethos musically, the album that then and now stands for what the dream of the sixties was about.

"Around the World in a Day’s" title track, the album’s opening song, begins with a hypnotic, wailing sitar that recalls Indian music (and, for most mainstream American listeners, the Beatles’ use of it) and then flows into a psychedelic groove that reminds you of 1960s sounds. It’s akin to announcing, “Here comes Prince’s take on the sixties.” The lyrics that follow confirm it. He begins, “Open your heart, open your mind,” speaking to the sort of optimism and spiritual freedom and intellectual curiosity that marked the sixties. He’s telling us of “a wonderful trip” on a train that’s leaving any time for which the price is only laughter. This is very hippie territory. When we get to the chorus where the refrain is “No shouting,” I feel like I’m in an ashram. The song ends with important but barely audible words, which in itself recalls the hidden messages of those late Beatles albums. Prince says, “A government of love and music boundless in its unifying power, a nation of alms, the production, sharing of ideas, a shower of flowers.” This is rose-tinted utopianism. This is unity, love and LSD. It’s relevant that he ends on the word "flower" because the image of the flower child, the peace-sign-sprouting woman with daisies in her hair, remains one of the enduring symbols of the dream of the sixties. When Boomers heard "Around the World in a Day" they may have felt it to be like sonic comfort food, a lovingly nostalgic recreation of their era’s sounds and its ethos.

But Prince wasn’t a Boomer star. He was the perfect age to be a wise and cool big brother to Gen X. Prince may be a generational hybrid, able to speak to both Boomers and Gen Xers (and, now, Millenials), but he’s a special icon for my generation. When we think of the 1980s and 1990s, we usually think of Nirvana or Tupac or R.E.M., but Prince’s surreal run of albums from 1982’s "1999" to 1992’s "Symbol," and the messages in his music that speak to the particular Gen X zeitgeist, make him a central figure for that generation.

One of the most important issues in the conversation between Prince and Gen X was sex. Gen X was more sexually aware and more sexually active at an earlier age than any other generation and, at the same time, we were fraught with anxiety because of the frighteningly rapid spread of the deadliest sexually transmitted disease in human history. Overlay those two developments with Prince’s intense sexuality, which is lustful and sensual and so knowing it seems like the product of more experience than anyone but a king with a harem could ever hope to have, and you can see why Gen X was filled with people who were hungry to hear what Prince had to say.

Excerpted from "I Would Die 4 U: Why Prince Became an Icon" by Toure. Copyright 2013 by Toure. Reprinted with permission of the author and Atria Books, a division of Simon and Schuster.

Shares