Without a doubt, book publishing is an industry in a state of flux, but even the nature of the flux is up for grabs. Take a recent example of the traditional tech-journalism take on the situation, an article by Evan Hughes for Wired magazine, titled "Book Publishers Scramble to Rewrite Their Future." The facts in the story are indisputable, but the interpretation? Not so much.

The news peg is the success of a self-published series of post-apocalyptic science fiction novels, "Wool," by Hugh Howey. Available as e-books and print books from Amazon, the series became a hit, and Howey recently sold print-only rights to a New York publisher, Simon & Schuster. Print-only because Howey and his agent determined that they were making plenty of money selling the e-books on their own.

Wired characterizes this as a "huge concession" on the part of Simon & Schuster, and in one sense it is: The publisher won't receive any e-book revenue, and it is in e-book format that "Wool" has seen its success so far. On the other hand, "Wool" is not only already very popular among the genre fans who made it an e-book bestseller, it's also an object of curiosity for the many otherwise-uninterested people captivated by Howey's rags-to-riches story in the Wall Street Journal. (By far the best-selling e-book by self-publishing exemplar John Locke is not one of his thrillers, but "How I Sold One Million E-Books.")

Yes, it's notable that Simon & Schuster shelled out a six-figure advance for this deal, but publishers have been known to offer similar advances for books that they only hope will find a large audience. "Wool" is that rare thing in book publishing, a known quantity, and a series on top of that, so there are multiple titles to sell. There is surely a sizable untapped market for print editions of "Wool" because e-books remain only 25 percent of the book market.

If print could talk, it would surely be telling the world, Mark Twain-style, that reports of its demise have been greatly exaggerated. The market for e-books grew exponentially after Amazon introduced the Kindle, and it's still one of the most fascinating and unpredictable sectors of a once hidebound industry. But the early-adapter boom is showing signs of flagging and the growth of the e-book market appears to be leveling out. E-books are definitely here to stay, but it seems that many, many readers -- a threefold majority, in fact -- still prefer print.

That's not, however, an angle the Wired piece pursues. Granted, Wired, like tech pundits in general, pushes a party line of impending, technology-driven, cataclysmic change; it's an excellent way to sell your services as a guru to business communities after you've freaked them out with your predictions. There's also a strong presence on the Internet of writers who are pissed off at publishers for rejecting their books or, having published them, failed to make a success of them. According to this faction, publishers are (or should be) terrified at the prospect of the recent boom in self-publishing.

On both parts -- Wired and the pissed-off authors -- this strikes me as wishful thinking. New self-publishing enterprises are a godsend for traditional publishers because they can take much of the uncertainty out of signing a new author. By the time a self-published author has made a success of his or her book, all the hard stuff is done, not just writing the manuscript but editing and the all-important marketing. Instead of investing their money in unknown authors, then collaborating to make their books better and find them an audience, publishers can swoop in and pluck the juiciest fruits at the moment of maximum ripeness. As Hughes points out, that's exactly what happened with erotica blockbuster E.L. James.

Why do self-published authors -- including James, Amanda Hocking and now Howey -- go along with this? Some, like Hocking, are simply tired of being publishers as well as authors and would prefer to devote themselves to writing. But for many the answer is simple: print. While most self-publishing platforms, including Amazon, do offer print options, they aren't able to effectively distribute print books to the best places to market them: bookstores.

You've probably read that bookstores, like traditional book publishers, are in trouble. They are, especially if they're big, overextended, relatively impersonal chain stores like Barnes & Noble. But, as the Christian Science Monitor recently reported, there are now many indications that a once-beleaguered portion of the bookselling landscape, independent bookstores, are enjoying a "quiet resurgence." Sales are up this year; established stores, such as Brooklyn's WORD, are doing well enough to expand and new stores are opening. Indies have been helped by the closure of the Borders chain and a campaign to remind their customers that if they want local bookstores to survive, they have to patronize them, even if that means paying a dollar or two more than they would on Amazon.

The rallying of the indies is a good sign for book publishers, who rely on bookstores and the people who work in them to introduce readers to new authors. As a recent study by the Codex Group revealed, book buyers go to Amazon when they already know what they want; they're not using the site for "discovery." That's why bookstores, although a relatively small locus for actual sales, are so important to the new-book ecosystem. Most people buy books on the basis of personal recommendations from friends, but many of those recommendations can be traced back to a bookseller or librarian. (And maybe the occasional reviewer!)

Amazon's own forays into book publishing, as Hughes notes, have not been a success, despite an investment in authors with either name recognition (Penny Marshall) or robust self-promotion machines (Tim Ferriss). The refusal of bookstores to stock these titles (which were, as they saw it, published by a rapacious competitor hellbent on driving them out of business), played a significant role in those failures.

"The real danger to publishers," Hughes writes, "is that big-ticket authors, who relied on the old system to build their careers, will abandon them now that they have established an audience." Yet it's hard to see why any of them would, if self-publishing would mean hiring a staff to replace the services provided by a publisher, from marketing and publicity to distribution and editorial. And you can be sure that -- whatever publishers' failings in providing such services to "little ticket" authors -- the people who write bestsellers get plenty of that.

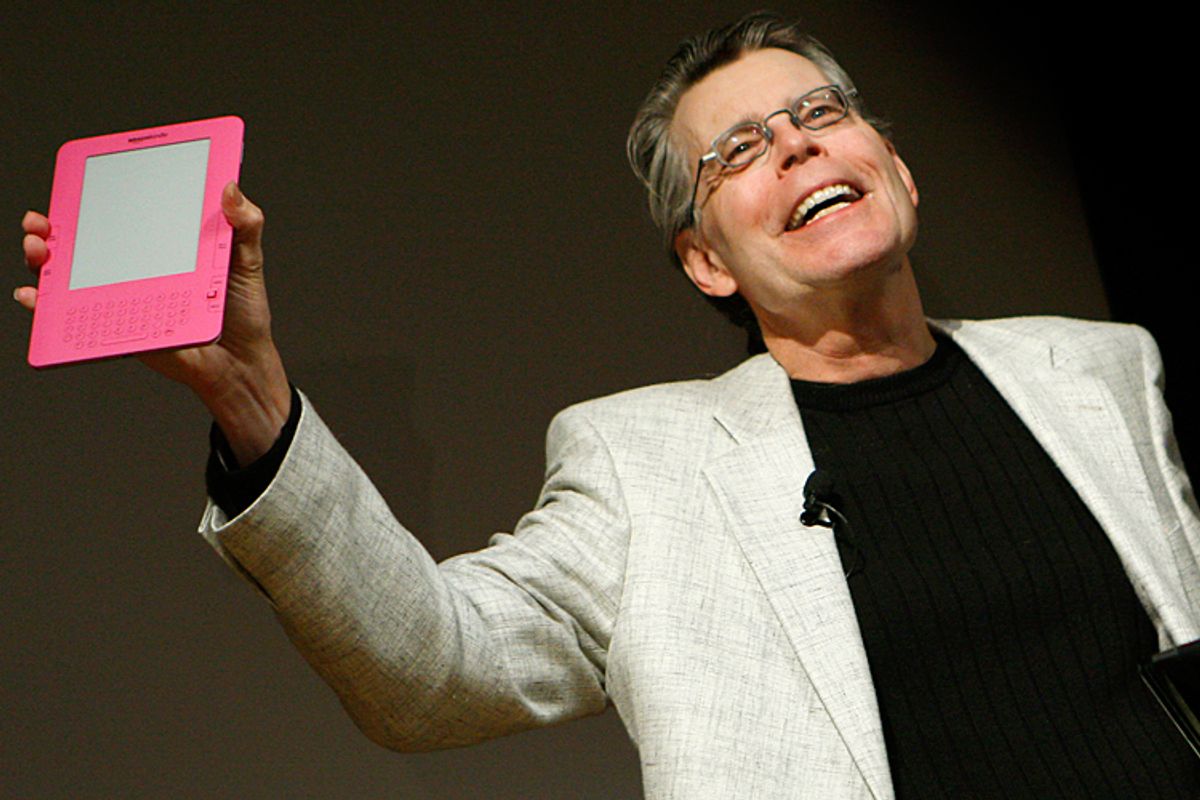

Furthermore, to switch to Amazon-style self-publishing would mean getting shut out of bookstores -- not a big deal for an author whose books weren't there to begin with, but a major loss for the likes of, say, Stephen King, who has always made his love of and gratitude toward booksellers well-known. Bookstores are where fans meet popular authors and get their books signed, cementing their devotion. Whatever a big-ticket author might gain in e-book royalties by taking the self-publish route would be more than offset by the losses incurred when the print editions of their books become less visible and available to their readers. I'll say this again: As exciting and new as e-books are, print is still 75 percent of the book market. And that's way too much to leave on the table.

Further reading

Evan Hughes for Wired on the future of book publishing

The Wall Street Journal on the success of Hugh Howey's self-published "Wool"

The Christian Science Monitor on the resurgence of independent bookstores

Shelf Discovery on the Codex Group on the minor role Amazon plays in new book discovery

Shares