A renowned Victorian explorer stands before his colleagues, accused of fabricating accounts of the strange beasts he encountered in a remote jungle. The explorer responds by challenging the most energetic of these detractors to join him in an expedition back to the site of his celebrated discoveries. That's the opener of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's "The Lost World," a ripping adventure yarn published in the early 20th century, with a main character, Professor Challenger, thought by many to be based on the real-life physiologist William Rutherford.

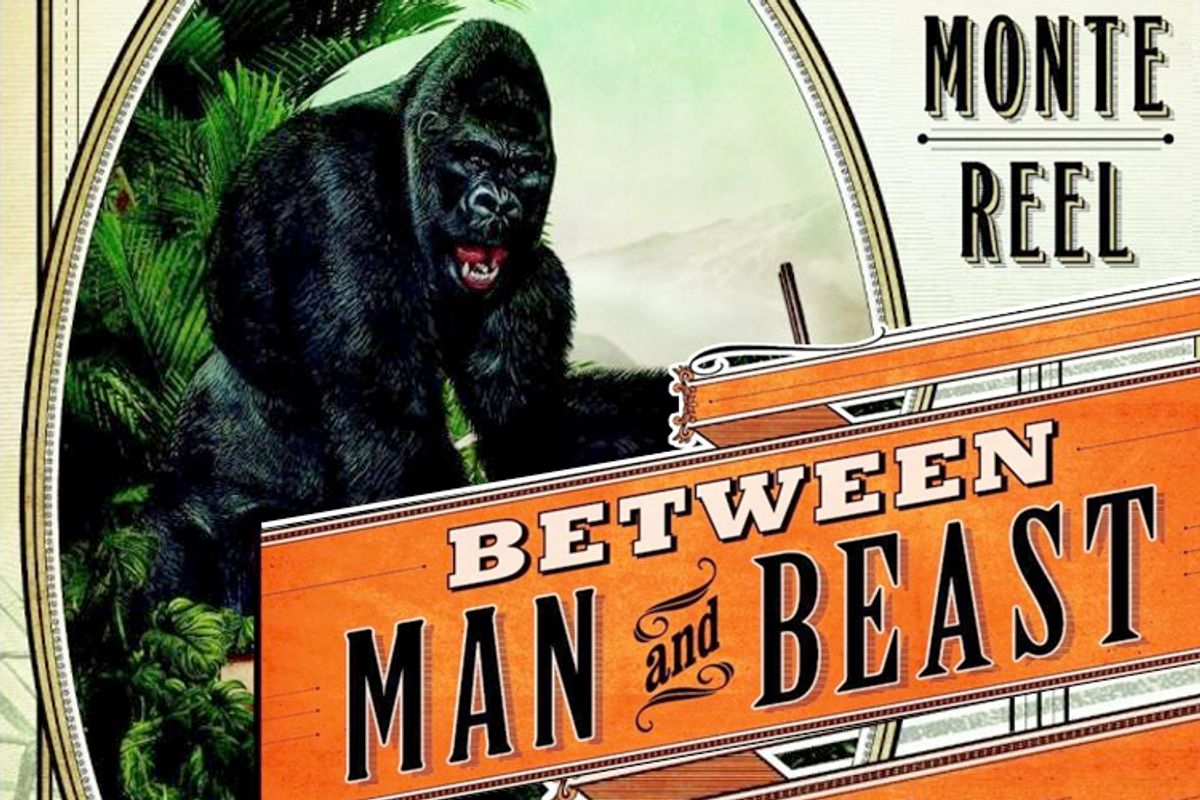

But as Monte Reel persuasively argues in his equally ripping (and far more intellectually satisfying) "Between Man and Beast: An Unlikely Explorer, the Evolution Debates, and the African Adventure That Took the Victorian World by Storm," another likely model for Challenger is Paul Du Chaillu, the first modern naturalist to observe gorillas in their native habitat. This elusive, gallant and endearing man was born on a date and in a place unknown, to a mother who has never been identified. His story, as told by Reel, is both a tale of plucky self-invention and an ironic reflection on the sometimes ugly inner workings of the scientific world.

The son of a French trader who operated an up-river station in the West African nation of Gabon, Du Chaillu first swam into the world's ken in 1848, at the age of about 17, when he appeared, bedraggled and diminutive, on the doorstep of the first permanent Christian mission in that nation. The missionary, John Leighton Wilson, happened to be a passionate amateur entomologist who liked to measure such interesting figures as "how fast a swarm of driver ants could consume a live horse or cow (48 hours)." Wilson and his wife adopted Du Chaillu as a surrogate son -- a type of relationship the explorer would form throughout his life, even into middle age -- educating him and helping him to land a job teaching French at a boarding school in upstate New York.

Always a misfit, if a cheerful and outgoing one, Du Chaillu parlayed his African experiences and American contacts into an expedition sponsored (meagerly) by the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences. His mission: to return from West Africa with a specimen of a gorilla, a fabled creature known to Europeans chiefly through skulls brought to their coastal settlements by native African traders. This was a tall order. As Reel notes, a full 60 percent of the British explorers sent to the region between 1816 and 1841 didn't make it out alive -- if hostile tribesmen didn't kill them, disease, animal attacks, drowning and other catastrophes often did. Furthermore, while most European expeditions lugged a staggering amount of gear with them (the famous David Livingstone "estimated his travel kit weighed about 11,000 pounds," and a typical crew included 100 to 160 porters), Du Chaillu's supplies could fit in a single dugout canoe (although it was a really big canoe).

Reel alternates between accounts of Du Chaillu's adventures in the jungle and the infighting among the members of the Royal Geographic Society in London over Charles Darwin's emerging theory of evolution. Du Chaillu bagged his gorillas and trucked their remains back to the U.S. But the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences refused to return his letters or requests for reimbursements, and when he resorted to exhibiting his specimens on Broadway, a bogus "creature" -- billed as a "link between man and monkey" and exhibited by P.T. Barnum -- upstaged Du Chaillu's genuine and genuinely remarkable finds. The book's two story lines converge when Richard Owen, superintendent of the natural history department at the British Museum, rescued Du Chaillu from obscurity by inviting him to London.

Owen was one of Darwin's staunchest and most energetic scientific adversaries. He was interested in Du Chaillu's gorillas because, Owen claimed (erroneously), the animals lacked a "hippocampus minor," a part of the brain present in human beings. This, according to Owen, proved that humans could not have evolved from gorillas. (The theory of evolution was still in its infancy, and even Darwin's allies sometimes asserted, incorrectly, that human beings might have evolved from present-day primates, or that some human races were "more evolved" than others.)

Taken under the wing of one of Britain's foremost men of science and feted by a public that became captivated by the idea of gorillas (Reel offers many amusing examples of the beast's appearance in popular culture), Du Chaillu became a celebrity. He dined with the Duke of Wellington and other luminaries, and his written account of his expedition was a bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic. Nevertheless, as Reel portrays it, the explorer's success was undercut by a nagging anxiety regarding the connections between gorillas and human beings. Whatever his sponsors might have said, Du Chaillu felt that the creatures he'd killed "had something of humanity" in them. Reel strongly telegraphs that this ambivalence was amplified by what he believes to be the primal secret of Du Chaillu's life: his mixed-race heritage.

The more resonant irony of Du Chaillu's story, however, lies in his trials among the English scientists. A zoologist who regarded Owen as a rival initiated an implacable campaign to impugn Du Chaillu's integrity. This detractor was joined by Charles Waterton, the prototypical great English explorer and a reflexively bitter enemy of any young aspirant to the title. Waterton insisted that Du Chaillu's descriptions of gorillas and their behavior was obviously wrong because it didn't jibe with what Waterton had observed of South American monkeys (he'd never been to Africa himself) or with the temperament of an infant gorilla he had discovered being exhibited as a sideshow attraction in England. (When this animal died, Waterton purchased its remains and had it stuffed "in a position of humiliating absurdity, complete with a set of donkey ears affixed to the top of the creature's head" and labeled it "Martin Luther After the Fall." Waterton was a Roman Catholic, and eccentric.)

Du Chaillu mostly served as a proxy target in long-standing feuds and contests he barely understood. I can't help wishing that Reel had made more of the fact that the scientists so intent on using Du Chaillu's discoveries to demonstrate the enormous differences between ape and man were conducting themselves exactly like any bunch of primates jockeying for social dominance. Du Chaillu -- described as "impish" and "elvin," and generally well-liked despite his gauche manners -- became collateral damage in such pissing matches. His veracity, his competence and his ethics were thoroughly besmirched, and there wasn't much he could do to defend himself, since the research he'd gathered during his expedition was limited by his very real lack of scientific training.

That's when Du Chaillu issued his own Professor Challenger-style challenge, and if his critics didn't take him up on it, other backers eventually did. A second expedition was assembled, and Du Chaillu showed the true content of his character by embarking on an intensive and comprehensive course of preparation. The journey, when it finally took place, did not unfold in any way like he'd planned -- it's one of the most exciting parts of "Between Man and Beast." But as Reel makes clear, right down to this book's final, eye-misting sentence, in the fullness of time Du Chaillu has been well and truly redeemed.

Shares