BRIGHTON, UK — Swapping out pieces in a game of chess is only a smart move provided you hold the most on the board, or at least the strongest position. But a new show at the Barbican in London suggests chess could be a “metaphor of exchange” between the artists it lines up. According to the theory, Duchamp swaps ideas with acolytes: John Cage, Jasper Johns, Merce Cunningham, and Robert Rauschenberg. And yet the Frenchman, superb chess player that he was, came out conceptually on top by the time of his death in 1968.

BRIGHTON, UK — Swapping out pieces in a game of chess is only a smart move provided you hold the most on the board, or at least the strongest position. But a new show at the Barbican in London suggests chess could be a “metaphor of exchange” between the artists it lines up. According to the theory, Duchamp swaps ideas with acolytes: John Cage, Jasper Johns, Merce Cunningham, and Robert Rauschenberg. And yet the Frenchman, superb chess player that he was, came out conceptually on top by the time of his death in 1968.

As things stood by then, Duchamp had relatively few pieces on the board. The Barbican exhibition collects most of the best known: his bottle rack, his urinal, his bicycle wheel, and his large glass. They are all here in replica form, a gesture that calls to mind a proliferation of chess pieces, the symmetry of left and right, of white and black on the board. Curator and artist Philippe Parreno has set them out right across a two-floor space in the Barbican’s Brutalist main building. Also in the space, two prepared pianos stand in opposition to each other and offer ghostly recitals by Cage while in the center is a dancefloor, also visible from the galleries on the upper floor, much like a board ready for chess.

Duchamp’s “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (The Large Glass)” (1915)

Duchamp’s “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (The Large Glass)” (1915)If this show, which also spent time in Philadelphia, is actually an extended chess metaphor, it presents a snapshot of the war of attrition between Duchamp and the visual arts. As with Beckett in literature, the Frenchman’s boldest moves still haunt anyone attempting to paint, sculpt, or draw their way into art history. And it is common, sobering knowledge that Duchamp appeared to give up art for a period in the early 1920s and devote his life to chess.

Now, we might take comfort from just how good he was at this alternative game. In 1931, Duchamp was a French delegate to the World Chess Federation (FIDE). He achieved the status of chess master and, with the help of tactician Vitaly Halberstadt, even wrote a book on, yes, endgame strategy. It got a title similar to the names of his gnomic artworks:Opposition and Sister Squares are Reconciled. Retroactively, at least, his newfound passion conferred a depth and intensity of thought upon all those throwaway Dadaist sculptures.

But one thing the show at Barbican reminds us is that chess once flourished in the same milieu as modern art. On display as both painting and print is a cubist portrait of the artist’s brothers going head-to-head at a game in a Paris café. Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Jacques Villon were doing nothing uncommon — chess was as commonplace in that long-lost cultural age as heated discussions on modern art. As a motif, the chess match is up there with the newspapers, wine glasses, and guitars of painting trailblazers Picasso and Braque. Today, you would have to replace all of those items with a laptop, tablet, or smartphone.

Marcel Duchamp, “Portrait of Chess Players” (1911)

Marcel Duchamp, “Portrait of Chess Players” (1911)In a 1964 interview with art writer Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp explained what appeal chess held for him. It comes as a surprise to find him talking about the game as an act of imagination, just without the mystery of art (the quote is taken from Calvin Tompkins’s recent book Marcel Duchamp: The Afternoon Interviews, published this year by Badlands Unlimited):

It’s complete. There are no bizarre conclusions like in art, where you have all kinds of reasonings and conclusions. It’s absolutely clear cut. It’s a marvellous piece of Cartesianism. And so imaginative that it doesn’t even look Cartesian at first. The beautiful combinations that people invent in chess are only Cartesian after they are explained. And yet when its explained there is no mystery. It’s a pure logical conclusion, and it cannot be refuted.

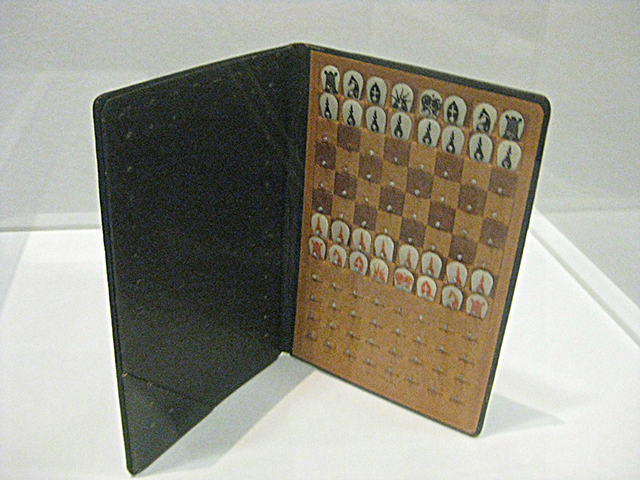

But life as a chess player must have been even less lucrative than the life of a pioneering artist in a century that wasn’t quite ready for him. In 1943, the emigré Duchamp designed a travel chess set, which he was all set to mass produce and market with a guarantee that pieces would stay in place. The current show features a leather-bound prototype, pieces all clinging to the vertical board. Look closely and you may detect a swoosh of equine power in his knights, a certain bloated quality to his bishops and a spectral imperiousness in his tiny queens. There is still an artist’s touch, albeit a subtle one.

Marcel Duchamp playing chess with John Cage (Image via parsons.edu)

Marcel Duchamp playing chess with John Cage (Image via parsons.edu)So what of the other players in this fabulous show? Cage was a chess fan but is said to have made silly mistakes, with which Duchamp was known to lose patience. When the composer asked the artist to teach him, Duchamp matched Cage against his wife Teeny. On other occasions, Duchamp would play his friend with one knight removed from his starting line up, the Duchamp handicap. And both arrangements were presumably fine with the American who after all wanted only to “be with him.”

One of the most curious displays in the fascinating chess-themed bay at this show is a chunky beige board, all pieces bar a handicapped knight in place, designed with the help of artist Lowell Cross. It has 24 output sockets and a rack of concealed photo-resistors and contact microphones. These were rigged up to control lights and electronic music throughout an exhibition match between Duchamp and Cage at the Sightsoundsystem Festival in Toronto, one of the former’s final public appearances.

Replica of Lowell Cross’s chessboard (Image via Rob Cruickshank / Flickr)

Replica of Lowell Cross’s chessboard (Image via Rob Cruickshank / Flickr)As for Johns and Rauschenberg, they get their chess dues from Duchamp with dedicated prints of his brothers in “The Chess Players.” Hooded eyes, bulging craniums and a jumble of pieces in the foreground are here the province of player and artist alike.

It is not clear what Merce Cunningham made of chess, but sporadic performances here at the Barbican show find dancers brought in according to game-like rules designed by the choreographer. Elsewhere, it is hard to look at Rauschenberg’s four-squared “White Painting” from 1951 without seeing so many white spaces on a game board.

Marcel Duchamp, “The Box of 1932″

Marcel Duchamp, “The Box of 1932″When it comes to talent, opening one door will often close another. And yet lines of mutual transit between chess and art remain open in the case of Duchamp.

1932: He publishes on chess and wins the Paris Chess Competition, but boxes up notes on chess in an ironic box from a department store.

1944: He collaborates with Man Ray on an exhibition called The Imagery of Chess, with help from Alexander Calder, Isamu Noguchi, Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, and Dorothea Tanning.

1966: He promotes an art show to support the American Chess Foundation, encouraging donations from 36 friends.

1968: At the time of his death, a work in progress turns out to be an erotic sculpture (“Etant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau/2° le gaz d’éclairage”), despite his supposed retirement.

But the least characteristic work by Duchamp included in this show has all the awesome mystery of art. The eight-foot-high photograph, “Door 11 rue Larray” (1964), looks at first like a Rauschenberg. But in fact this contains a view of the Frenchman’s apartment in Paris. Duchamp fitted this door in a hall, so that when it shut on the bedroom, it opened on the bathroom and vice versa. It rejects the French saying that a door must either be open or closed. So, in fact, the door is always ajar: neither chess nor art, but something else ineffable.

The Bride and the Bachelors: Duchamp with Cage, Cunningham, Rauschenberg, and Johnsis on show at the Barbican Center (Silk St, London EC2Y 8DS, UK) through June 9.