A SIMPLE SEARCH for Tom T. Hall’s song “Redneck Riviera” on iTunes yields nearly 30 hits by that name or some variation thereof. There’s “Redneck Riviera” by Hall, but also “Redneck Riviera” by Gary P. Nunn, Shawn Radar, Thomas Michael Riley, Dr. Breeze, Bang, The Beer Dawgs, and Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. There’s “Queen of the Redneck Riviera” by Larry Joe Taylor, “Humanity Night on the Redneck Riviera” by John Reno & The Half-Fast Creekers, and “On the Redneck Riviera” by Stop the Truck. There’s a comedy routine called “God Bless Redneck Riviera” by Ronald Reagan’s former director of fundraising, T. Bubba Bechtol — who I initially misidentified as T. Bubba Brecht, and thought I was onto something brilliant. But whichever “Redneck Riviera” you choose to listen to, twanged out or bluesy or spoken word, the message is basically the same: spring break forever. Sunsets over white hot sand, cold beer and cheap motels, no clothing and thus no rules, a party that won’t quit, paradise, the promised land, destiny carried in on the wings of a cool breeze and the reeling touch of a beautiful woman, or ten.

Not that that’s too different from the Redneck Riviera’s now-ironic namesake, the French Riviera of the 1920s and 1930s, when American tourism was enjoying its first boom on the heels of the original spring breakers. Before Cannes became a thing that the creative class did each May, before Art Deco hotels and models sunbathing topless on yachts, much of the Côte d’Azur basked in a shabby ruralism not unlike parts of the Florida Panhandle today. Intriguingly, it was the business of making movies that brought high culture to the lowly Riviera in a lasting way. With studios like MGM and 20th Century Fox paying the Victorine in Nice to produce American talkies, the consumption of beachside space from Toulon to Menton took off after the arrival of Rex Ingram, Alice Terry, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks for nonstop parties on the Promenade des Anglais. Affectionately dubbed “Little Hollywood,” the Riviera entered into the pop consciousness riding the coattails of Big Hollywood’s Golden Age.

But if I dim ever so slightly the glow that emanates from all things jazzy and boozy and generationally lost, the gulf of cultural difference separating F. Scott Fitzgerald from Tom T. Hall — and, for my immediate purposes, Harmony Korine’s new film Spring Breakers — seems to contract. After all, the Riviera was nothing more than a place to be “entertained,” according to a euphemistic John Dos Passos, “with a great deal of gin fizz” and “wonderfully good bathing.” Antibes was a paradise of uncounted weeks spent drinking and dancing naked on the beach, Juan-Les-Pins a promised land where artist Gerald Murphy and his wife Sara slept under pine trees and woke up hungover to eat “Heinz Beans in Tomato Sauce with and without pork.” “Have you ever tasted Libby’scanned Sweet Potato and Corn on the cob?” Gerald asked in a paeanic dispatch. “My god.” True, the Hôtel Martinez was no Motel 6. But the earnest desire for unreal and absolute pleasure, a break from life’s daily disappointments — that was the same kind of destiny calling.

Implicit in Hollywood’s Continental drift, then, is a twinned sense of tourism’s magical offerings: the warm gin fizzy fantasies one could both live and act out on the Côte d’Azur, the eclipses of the self imaginatively secured through travel on the one hand, and acting on the other. Nowhere was this more evident than in Fitzgerald’s 1933 novel Tender Is the Night, in no small part the story of 18-year-old Hollywood starlet and spring breaker, Rosemary Hoyt, who is “spiritually weaned” from her dewy ideals about life, love, and the movies on the banks of the Riviera. Rosemary’s transition from baby-faced star to glamorpuss takes place under the influence of Dick Diver, equal parts father figure and lover, who is under the influence of his own demons. But to Rosemary, a young actress newly inducted into the lush life of Americans on the beach, Diver seems “kind and charming — his voice promised that he would take care of her, and that a little later he would open up whole new worlds for her.”

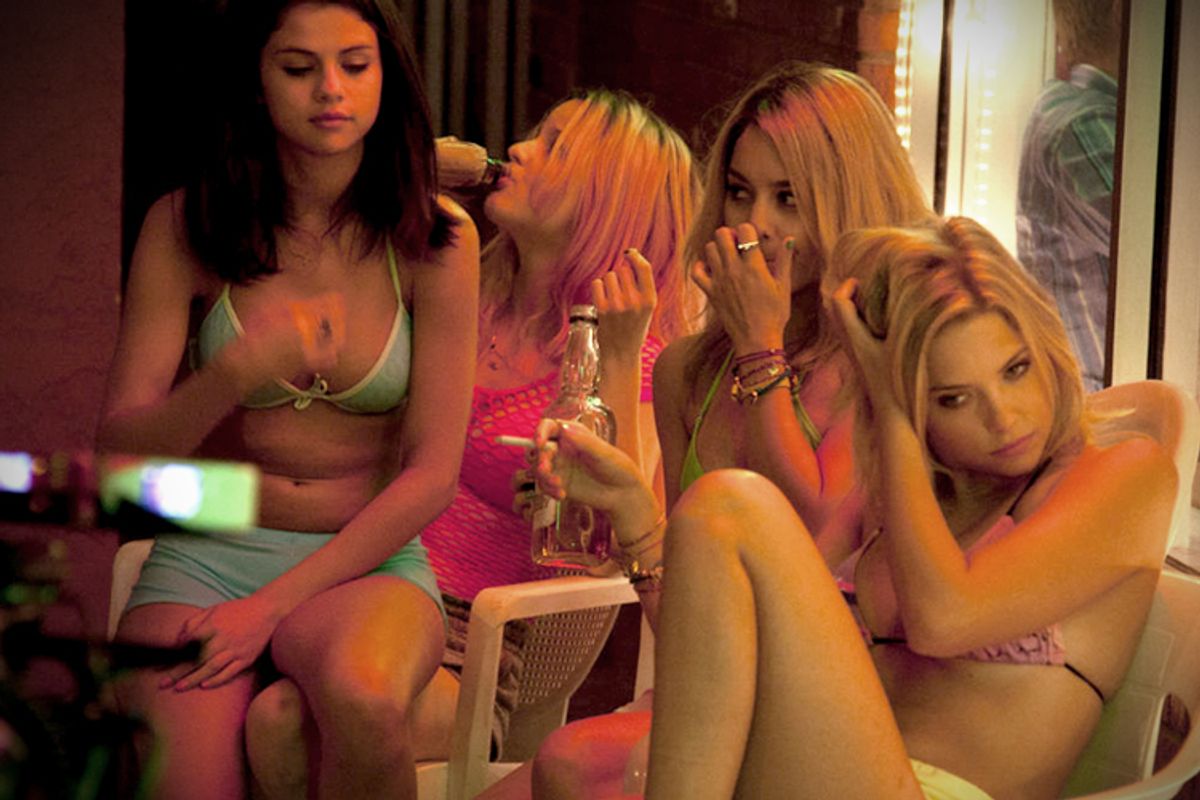

For those who have borne witness to Korine’s great, gleeful Spring Breakers, some of this should sound familiar. Where Fitzgerald transported his 1930s Hollywood ingénue to the seashores of Nice, Korine brings to the Redneck Riviera Disney’s newest princesses — Selena Gomez, Vanessa Hudgens, Ashley Benson — with his wife Rachel Korine along for the joy ride. (One of these things is not like the other, and it’s fun, if pointless, to wonder why.) On spring break from their uninspired college lives, the girls drink, dance, fuck, and fall in love with the mesmerizing Alien (James Franco), a rapper-entrepreneur who saves them from a two-day jail stint so they can keep living large in the promised land. Toeing the line between teacher and kink master, Alien also opens up a whole new world of thug life to his quaking Mouseketeers: the chance to experience something, and thus to become someone, new. The plot sort of ends there, but it’s a tale as old as literary time. “Close my eyes,” Alien intones, “every time I look, they are like old fashion bitches, straight out of a book.”

Of course, I’m not claiming that Tender Is the Night, or any other work of literature, is Korine’s high culture ur-text. But I do want to point out that the promise of spring break goes way back in American culture, predating Girls Gone Wild and the hushed pledge that what happens in Cancun stays in Cancun. The possibility for self-transformation unites a vast range of artistic productions as disparate as expatriate novels, country music, and stories of girls behaving badly away from home. (Think, for example, of Amanda Knox, whose memoir is slated for release next month.) In a smart inversion of cultural history, this is Hollywood riding the coattails of the Redneck Riviera to make a point that’s so deep-seated in our cultural consciousness we might not even recognize its reach.

Korine, for his part, does a bang-up job transmuting the fantasies of 1920s France to 2013 Florida, the old fashioned book to the digitally punctured cinematography of Spring Breakers. If the seashores of Nice were brought into hazy relief by Fitzgerald’s sensory modernism (the Riviera’s opulence “a thousand conveyers of light and shadow,” “the totality of […] refraction”), the Panhandle also materializes as a mirage of sorts. Everything Korine touches turns too bright, too loud, and too big, in a way that’s not unpleasant, only unreal. The screaming crowds and crowded breasts are, no doubt, their own world of uncanny excess — but so are the burnished peaks of the sun setting over dubstep, the late afternoon photographer’s light that makes four young girls kicking their legs in the ocean an act of magical transformation. Like Tom T. Hall swears, spring break is more than just a good time. It’s a spiritual plane that promises a higher, faster, and freer way of being in the world, a transcendence of self that neither the church prayer circle nor the college lecture hall can deliver.

In short, it’s the perfect place for Hollywood to amplify the transformative doubling of touristic ecstasy and losing yourself in the world of performance art. In this sense Spring Breakers is an extended lesson in dramatic form for Korine’s angels, a skills workshop on method acting led by Franco and the topless denizens of the Redneck Riviera. (As Gomez recently confessed on The Late Show with David Letterman, “We were actually on real spring break with real jocks and girls taking their clothes off and stuff.”) Say what you will about Franco (and I certainly have) it’s hard to deny his commitment to both pop culture and to himself as a pop culture icon. That too is a kind of pseudo-religious sentiment, a love of one’s own visibility and vulnerability whose meta-mark is all over the film. Most obviously, it’s in the realization that Korine’s cast members, be they Disney princesses or PhD performance artists, can’t be separated from their prior selves in the eyes of a pop savvy audience — or at least the selves we think we know.

Here Franco channels that self-reflexive love of pop as a camp so concentrated we can’t help but buy into it as some version of reality. Around the one-hour mark, Alien runs away with the movie, leaving his bad bitches to stare with genuine amusement as he smokes up, cokes up, and tinkles Britney Spears’s “Everytime” on the piano. (Last year, Franco was the producer and director of an ill-fated musical theater production of Spears’s oeuvre for Yale undergraduates. It seems Korine let him take over the directing for a stretch.) When the girls join him in his slow-mo “Everytime” rampage — Spears’s raspy voice begging “Notice me” over and over again — we can almost hear Rosemary Hoyt speaking to us from some far away place. “Oh, we’re such actors — you and I!” To be sure, that’s what Franco and his ladies-in-waiting are. But in their shared destiny as self-conscious performers, trying hard to alter our sense of pop consciousness with sex, drugs, and rock and roll on the Riviera, they’re also each other’s “motherfuckin’ soul mates.”

All of which is simply to say, Spring Breakers isn’t really about the objects of youthful hedonism writ large. At the film’s emotional core is the yearning for the unreal to become real, for fantasy to materialize as truth you can escape your way to. Lose yourself at the beginning only to find yourself at the end; it’s not new, and it’s not complicated. It’s as simple as a land breeze picking up surf, a cold cocktail, a salty kiss stretched beside you on the beach, or having a good time watching actors having a good time in a movie. Lucky for us, we suffer neither the disillusionment nor the hangover of realizing that, like all grand good things, spring break must come to an end.

After all, this is the fucking American dream.

Shares