The Supreme Court oral arguments on marriage equality deserved all the attention they received -- but it's another case heard this week that will affect even more people over the course of their lifetimes. And it could cost Americans millions in prescription drug bills.

The case falls within a sadly predictable continuum for the Roberts Court, which virtually always sides with the corporate litigant over the government or individual. This time, the arguments in FTC v. Actavis revolve around an insidious tactic common to the nation’s largest drug companies, and known as “pay for delay.” As a result of the likely ruling in this case, drug companies will be able to charge consumers as much as five times the potential cost of their products. And both government regulators and consumers will watch helplessly as pharmaceutical companies bribe generic drug makers to retain their exclusive holds on the lifesaving medicines we all inevitably require.

The first thing to know here is that U.S. pharmaceuticals get a very good deal from the federal government. For every new drug they produce, they get rewarded with long-term patents that grant them exclusive rights to market and sell the product for as much as 20 years – which guarantees them billions in profits and no competitors in the marketplace. Drug companies claim that they must be allowed to profit off of products they nurtured with expensive research and development. In reality, taxpayer-funded research from academia or the National Institutes of Health account for the vast majority of vital drugs brought to market every year, and R&D is a small fraction of the overall drug company budget. What’s more, drug companies routinely use their monopoly power to jack up pharmaceutical prices, which cost far more in the U.S. than anywhere in the world.

Congress tried to deal with this problem as far back as 1984. The Hatch-Waxman Act accelerated the FDA approval process for generic drugs, essentially copies of the brand-name products. Typically, generics sell at a much lower price – in most cases by 80-90 percent, which obviously makes them quite popular. So the introduction of a generic drug basically ends the profitability for the brand-name manufacturer, while delivering big benefits to the consumer. Under Hatch-Waxman, companies can sell generics before the expiration of the exclusive patent by successfully challenging the patents’ validity (and there are often grounds for such a challenge, as drug company lawyers often find every loophole imaginable to extend their patent life or acquire new patents for slightly different versions of the same drug).

So, imagine you’re a big-time drug company. You want to keep competitors off the market as long as possible. Your move is to basically sue the pants off the generic drugmaker for copyright infringement, setting in motion a long and tortuous legal process. And these usually end with “pay-for-delay” deals. The brand-name drug company pays the generic manufacturer a cash settlement, and the generic manufacturer agrees to delay entry into the market for a number of years. In the case before the Supreme Court, the drug company paid $30 million a year to protect its $125 million annual profit in AndroGel, a testosterone supplement.

It’s hard to see this as anything but bribery, designed to preserve a lucrative monopoly for the brand-name drug maker. In fact, this is what the Federal Trade Commission has argued for over a decade. They consider it a violation of antitrust law, arguing that the exchange of cash gives the generic manufacturer a share of future profits in the drug, specifically to prolong the monopoly. As SCOTUSBlog summarizes from the FTC’s court brief, in the regulator’s view, “Nothing in patent law … validates a system in which brand-name companies could buy off their would-be competitors.” Indeed, everyone wins with pay-for-delay but the consumer: the FTC estimates that the two dozen deals inked in 2012 alone cost drug patients $3.5 billion annually, with the brand-name and generic manufacturers splitting the ill-gotten profits.

The FTC has petitioned the courts a half-dozen times to shut down these pay-for-delay deals, with no success. Federal courts accepted the drug industry’s view that the deals are just standard legal settlements, which honor the patent arrangement, and do not delay the introduction of generics beyond that period. But last October, the 3rd Circuit ruled in the FTC’s favor in a deal involving the blood pressure medication K-Dur, arguing that these deals were presumptively illegal unless proven otherwise. Only then did the Supreme Court step in and decide to rule in the case. But they did not use the 3rd Circuit opinion, but a separate ruling out of the 11th Circuit, where the Appeals Court agreed with the drug companies on the harmlessness of pay-for-delay in the AndroGel case.

This is critical, because Justice Samuel Alito recused himself from the case, citing prior involvement. That creates the potential for a 4-4 split on the Court. If the Court heard the 3rd Circuit case and deadlocked, that case would stand and perhaps get used as precedent. By hearing the 11th Circuit case, a tie upholds Big Pharma’s argument that pay-for-delay schemes are presumptively legal, and the 3rd Circuit decision would essentially wither on the vine.

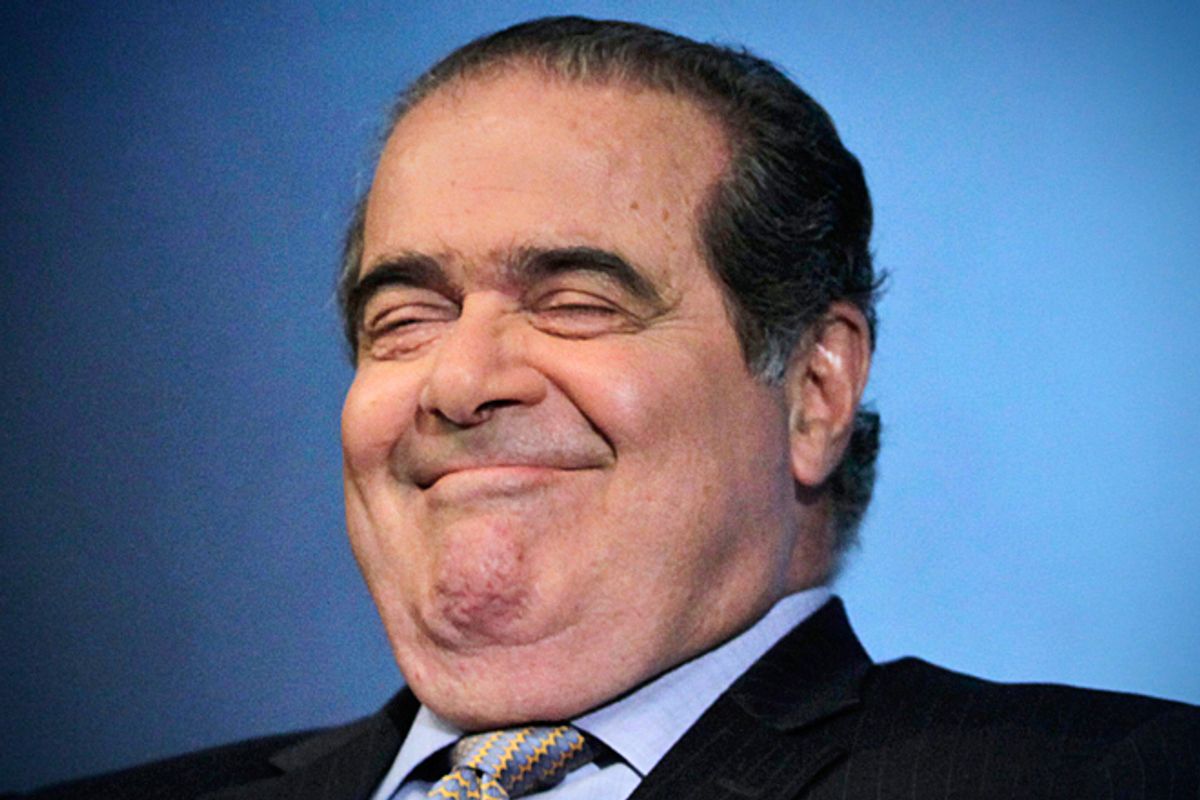

The eight remaining justices heard the case Monday, and as expected, the majority took the side of the drug companies and their monopoly rights. Justice Antonin Scalia argued that drugmakers could not be participating in illegal activity if they were “acting within the scope of the patent” (but the whole point is that the generic manufacturers were challenging the validity of the patents in the first place). Even Justice Sonia Sotomayor questioned whether the existence of a payment was enough to make the activity illegal. Justice Stephen Breyer weakly suggested punting to the district courts to let them make the determination of illegality on a case-by-case basis, but more justices lined up with the skeptical takes of Scalia and Sotomayor. You can read the transcript of oral arguments yourself.

The most surefire statement about the Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Roberts is that corporate interests will win the day. In the 2011-12 term, the Court sided with every case on which the U.S. Chamber of Commerce filed a friend-of-the-court brief, according to the Constitutional Accountability Center. In highly publicized cases like Citizens United and dozens of smaller but no less critical ones, the Court, especially the conservative wing, has tilted toward corporate concerns dramatically, at the expense of ordinary individuals.

In this case, the Chamber of Commerce did not take a position, but practically the entire pharmaceutical industry presented amici briefs in the case, as well as the National Association of Manufacturers, who claim that the FTC’s position would “have an immense impact on the economy.” And even with Alito’s recusal giving the opportunity for a deadlock, the oral arguments strongly suggested that drug companies would get their way.

Nobody lined up for three days waiting to hear arguments in FTC v. Actavis. Nobody stood outside with placards urging the justices to rule one way or the other. But the impact is undeniable. Drug companies basically try to preserve their government-granted monopolies as long as possible, and they routinely pay off their competitors to stay out of the market. The results cost you money. In a case in California over the antibiotic Cipro, the state asserted that one brand-name pill today costs $5.30, but with a generic competitor, the price would fall to $1.10. Multiply that by the size of the marketplace and you have $3.5 billion a year and counting siphoned from sick Americans, for the benefit of drug industry treasuries.

Regardless of how the Supreme Court rules on marriage equality, the corporate takeover of the judicial branch remains one of the most troubling elements of American life in the 21stcentury. Progressives lauding advances on social issues might want to also pay more attention to the chaining of the courthouse door to ordinary Americans on bread-and-butter economic concerns, and the troubling rise of a Golden Age for corporate abandon.

Shares