"No. And no again. Not that." So says Serena Frome, the narrator of Ian McEwan's 2012 novel, "Sweet Tooth." What she's protesting is a story written by her lover, Tom, in which an author at work on her second novel is scrutinized by a worried companion, a talking ape. "Only on the last page," Serena explains, "did I discover that the story I was reading was actually the one the woman was writing. The ape doesn’t exist, it’s a specter, the creature of her fretful imagination."

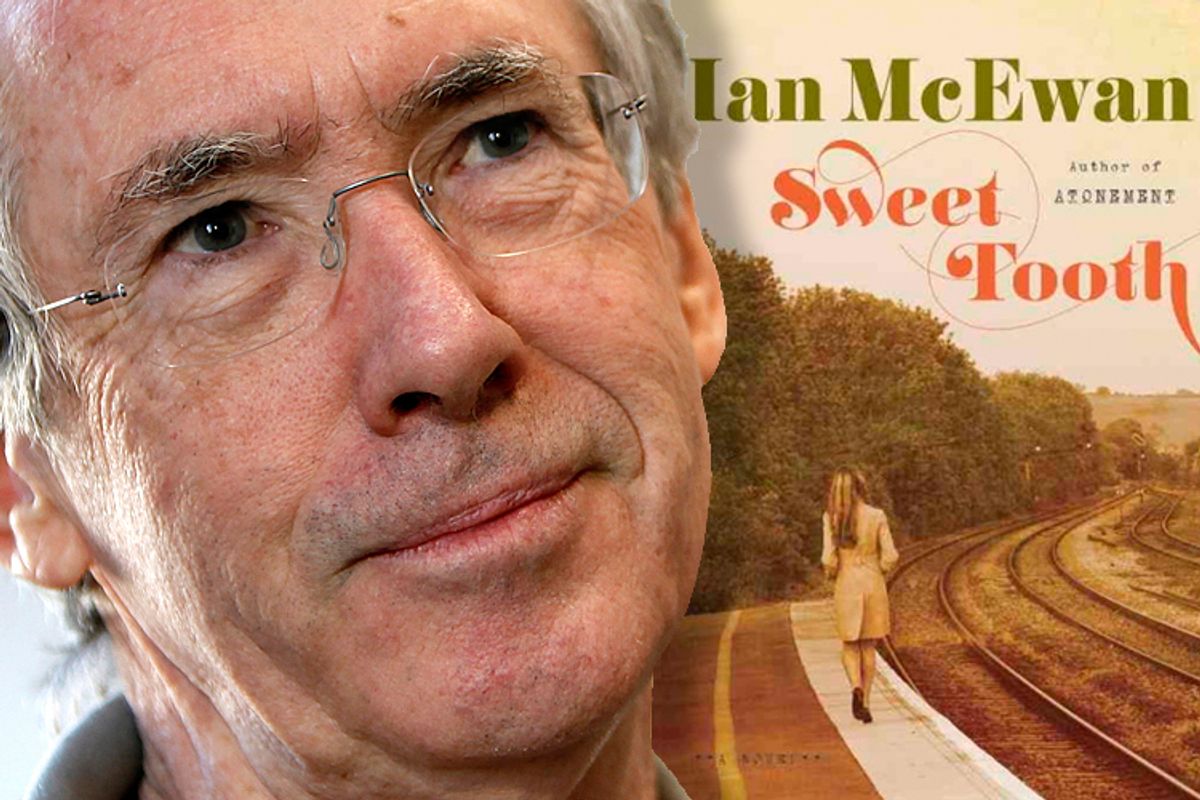

Serena, who has been earlier established as a certain type of hungry but unintellectual reader, dismisses this device as a "trick" to be "distrusted." "There was, in my view," she observes, "an unwritten contract with the reader that the writer must honor. No single element of an imagined world or any of its characters should be allowed to dissolve on authorial whim."

She has plenty of company in that sentiment. The other day, a colleague complained to me about a recently published first novel, "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards" by Kristopher Jansma, which features the same gambit, only doubled. The book's first five chapters are about a young man of modest North Carolina origins who aspires to be a writer, befriends a wealthy but tormented literary savant in a workshop and falls for the savant's actress friend. Then, "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards" informs its readers that what they have just read is a novella written by a similar guy, based on the events of his own life. And then, when you get to the end of "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards," after the characters have traipsed through several exotic locales, the last chapter describes a book editor discovering a manuscript left for her in an airport. Its first sentence is the first sentence of "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards."

My colleague was annoyed by this, as many readers were exasperated by the revelation, at the end of McEwan's 2001 novel, "Atonement," that the preceding story was actually supposed to be an autobiographical novel written by a fictional character. She (the invented novelist) confesses to altering some of the events she has fictionalized in order to achieve a happier ending than her characters enjoyed in real life.

There are times when "Sweet Tooth" appears to be an extended conversation with those readers who were miffed by this 11th-hour twist in "Atonement." "Sweet Tooth" is a playful and conciliatory gesture of empathy -- although you don't realize that until you get to the end and learn that what you've just read is (yes!) not Serena's account of her own life, but a novel that Tom has written in an attempt to understand her better. Serena, it's certain, would have hated the ending of "Atonement," even if it was more resonant and considered than Tom's gimmicky ape story. "I wanted to feel the ground beneath my feet," she complains about such authorial high jinks, and "Atonement" certainly does whip away the foundation on which its readers have been standing.

But maybe that foundation was never very sound? According to Geoff Dyer, who reviewed "Atonement" for the Guardian when it was first published, any careful longtime follower of McEwan's work would have been unsettled from the very beginning of that novel. Such a reader would have immediately perceived that the first section is "perversely ungripping … a lengthy summary of shifting impressions" in which the many "pallid qualifiers and disposable adverbs" form a "pastel haze" that betrays the undue influence of Virginia Woolf. This, as Dyer suggests (while trying to avoid giving away the twist), is because that part of the book is not written by the same Ian McEwan whose "cinematic clarity and concentration of dialogue and action" Dyer has so admired; rather, the first part of "Atonement" is not very good because it is meant to have been written by the less-talented (and entirely imaginary) Briony Tallis.

Jansma, like McEwan, intends his novel to convey something about the way writers think and function in the world, and about the way fiction reflects real life through the twisted mirror of longing. To begin your novel with a feint -- a novel-within-the-novel that only announces itself as such after the fact -- is a legitimate way to do this, but for readers like Serena Frome, it can register as a violation. That's because it's a bait-and-switch, a work presenting itself as one kind of story then revealing itself to be another. (This, incidentally, is also what Serena does to Tom. He thinks he's having an affair with the representative of an arts foundation that has awarded him a grant. However, Serena really works for an intelligence agency that's sponsoring Tom in hopes that he'll produce pro-Western, anti-Soviet writings.)

Although postmodern novels often use devices that unsympathetic readers sneer at as mere "tricks," this particular move literally is a trick: The reader has been fooled into thinking she's engaged in one form of imaginative enterprise, only to have its satisfactions denied her. If she wanted to read something cunning and metafictional she would have picked up a book that clearly signaled itself as such. In this respect, her disgust does not seem unwarranted. After all, no Mark Danielewski fan (for example) is in danger of opening one of his books and finding within it the cuckoo's egg of a long section of exquisitely rendered, Alice-Munro-style realism.

One way to tip off the reader that you intend to pull a maneuver like this is to make the initial "fake" narrative obviously bad. That's what Dyer feels McEwan has done in "Atonement." And that is what I thought Jansma was doing as I trudged through the first five chapters of "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards," having been informed beforehand of the coming metafictional twist. If the badness of the first part of "Atonement" is pretty subtle -- very few readers besides Dyer seem to have picked up on it -- Jansma, I thought, was really ladling it on. The beginning of "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards" has the undercooked, derivative romanticism of a freshman infatuated with F. Scott Fitzgerald. It's jam-packed with clichés lifted from both books and films -- a debutante complaining about having to smile all the time, a goth girl who writes stories about dead babies and pins a poster of Edgar Allan Poe on her wall, the gay genius friend who drinks too much and dispenses catty, witty quips, plus a lot of mooning around over an icy blonde who is more a collection of inexplicable, dated behaviors than an actual character.

Jansma seems to be aware of these shortcomings. By the time you get to the middle of "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards" he has his narrator, now unveiled as the author of the preceding novella, quoting the rejection letters his manuscript has elicited from literary agents: "'forced,' 'unrealistic,' 'fantastical,' … 'emotionally dishonest,' and 'frankly, simply not believable.'" That sounded just about right to me. Furthermore, Jansma's book-within-a-book contains a short story written by the twice-fictional narrator, which in turn contains excerpts from a historical novel this character is working on. If the first five chapters of "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards" are rather bad, the short story within it is worse yet. And the historical novel within the short story? Really bad, comically so.

Surely any novelist who can create so many nested gradations of badness must know what he's doing, right? Halfway through "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards," once I had made it past the hurdle of the book-within-the-book revelation, I felt considerable suspense. Would the novel now become something worth reading, and thereby make up for all the time I'd spent with the tedious, unnamed initial narrator and his store-bought dreams? If so, what superhuman confidence Jansma must have had in both his concept and his execution! How could he be so sure readers would persevere through those first five chapters? If my colleague hadn't given me reason to expect that the novel, at some point, would change drastically into something else, I would have given up on it long ago.

Unlike Serena Frome, I'm rather partial to authorial "tricks," although I also enjoy the kind of fiction Serena likes, the sort that has "life as I knew it re-created on the page." (Side note: McEwan, who rejects fiction with any element of fabulism, is really not in a position to needle anyone over the narrowness of her tastes.) These appetites are not mutually exclusive, and those of us with sweet teeth can also savor the savory.

I was irritated by "Atonement," however, not because I felt betrayed on learning that the characters I'd been reading about were not "real" within the (invented) world of McEwan's novel. Instead, I found the point of the novel -- that fiction, rather than representing life as we know it, is a burnished and manipulated version of reality, shaped by both art and the artist's unresolved desires -- banal and patronizing. I, and presumably most readers of novels like "Atonement," really are aware of how fiction works, I wanted to tell McEwan; we aren't simpletons. The pleasure of reading fiction lies in believing what we know to be untrue (even when we also know that sometimes it's based on the author's own experiences).

Nevertheless, one thing that intrigues me about "Atonement" is possibly unintentional: the way its author is felt to be intruding in the relationship between the reader and the illusion the writer himself has conjured. At a certain point in any good reading experience, the reader's imagination melds with the writer's words. The result is something more than just the sum of the author's vision as it battles, or succumbs to, a reader's expectations for a certain kind of story.

Reading, as Mohsin Hamid observes in his novel "How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia," is a creative activity. In real life, a person stares at "black squiggles on pulped wood," but within, a mini-Genesis is going on. "To transform these icons into characters and events," Hamid writes, "you must imagine, and when you imagine, you create. It's in being read that a book becomes a book." And every one of those readings -- every reading of, say, "Sweet Tooth" -- is different because every reader is different. The idea that the author alone gets to determine how his or her book is experienced seems a more delusional fantasy than any reader's benign, temporary attachment to invented characters. "Readers don't work for writers," as Hamid puts it. "They work for themselves."

This is something more novelists might want to bear in mind. While it is undeniably clever to present five chapters -- or a whole volume -- of weak fiction as a preface to a masterful exploration of the writer's life, you better be very sure you can deliver on the second part of the plan. "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards" becomes, in its latter half, less naive, and literally more worldly, taking its burnt-out narrator to Dubai, Gabon, Iceland and Luxembourg. But the novel never loses the canned and processed quality of its initial chapters, the sense that the fictional world it summons is derived not from any lived experience, but from secondhand narratives, particularly television. I'm not talking about "Six Feet Under," either, but something more along the lines of a Family Channel series starring five indistinguishable 24-year-old actresses in designer shoes pretending to be high school students.

Just one example: The narrator of "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards" has turned from writing fiction to teaching writing. He stands before his rapt students preaching a garbled gospel celebrating "plagiarism" (freely muddled with fabrication) and scamsters like James Frey and Stephen Glass. So cynical! Then, to illustrate his cavalier attitude toward the job, Jansma has the teacher gather his belongings in the empty room after class and dump all his students' term papers in the wastebasket as he heads out the door.

It's an action that would never occur in real life. Even if a teacher were inclined to do this -- and you have to wonder what happened to the customary pedagogical practice of returning marked papers to their authors -- he would never do it in the very classroom where he teaches. Not only would he be much more likely to get caught, but chances are the papers would be returned to him by a conscientious janitor who assumed they were tossed by mistake. This is, however, exactly the sort of thing you'd see on television, where the creators have 20 seconds to convey the character's irresponsibility and have to do it dramatically.

Much of "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards" is similarly borrowed or allusive; Jansma cribs elements from works by Hemingway and Henry James as well as Hollywood movies and celebrity culture -- these could be homages, but they could also be crutches. "That's what it all is now," the blonde actress remarks, after she's pulled a Grace Kelly and (I kid you not) married the prince of Luxembourg. "Everything reinvented! Nothing genuine." This exclamation comes near the end of the novel and gave me pause -- could Jansma even now be faking me out? Could the bogus teleplay gestures, the ongoing badness, the slippery, synthetic falseness of "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards" as a whole be intentional? He had, after all, introduced any number of ludicrous events, such as having the narrator attacked by an actual leopard while standing by a desk in a book-lined study. (The house was in Africa, but still.)

To produce a novel that was entirely and deliberately bad -- not merely bad at the beginning as part of a plan to tease readers about their desire for naive realism -- would be a truly daring artistic move. The danger, of course, is that people will assume you are simply a bad writer, a risk all the more pronounced when this is your first novel. It's true, the narrator of "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards" is exactly the sort of writer who would produce a self-involved meta-narrative, but Jansma could be, as well. And surely if Jansma were so fiendishly clever as to devise such a plan, he would have done so in service of a more interesting theme than that most tiresome of authorial assertions, that fiction writers tell "lies."

Honestly, guys, we already know that. And isn't the point of a fiction writer's lies that the reader wants to believe in them, and allows herself to do so for the brief duration of the reading? Not only is "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards" unbelievable, I never for a moment felt the least inclination to believe in it. You can't play around with your reader's investment in fictional characters and scenarios unless you can persuade her to make the investment in the first place. McEwan, for all his patronizing assumptions about how his novels are read, has always been able to do that, even when he is (perhaps!) purposely writing in an inferior style. He may be patting you on the head, but he hasn't lost his ability to charm.

Now, having finally finished it, I still can't quite get a bead on "The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards": Just how much of its badness is meant to be bad? Is any of it at all meant to be good? No doubt this makes me a less than ideal reader of the novel, however much I like to think of myself as a literary omnivore. Perhaps I am even as clueless and vulgar a reader as Serena Frome. Whatever the case, I don't work for Jansma, so he can't fire me. But I can always quit.

Shares