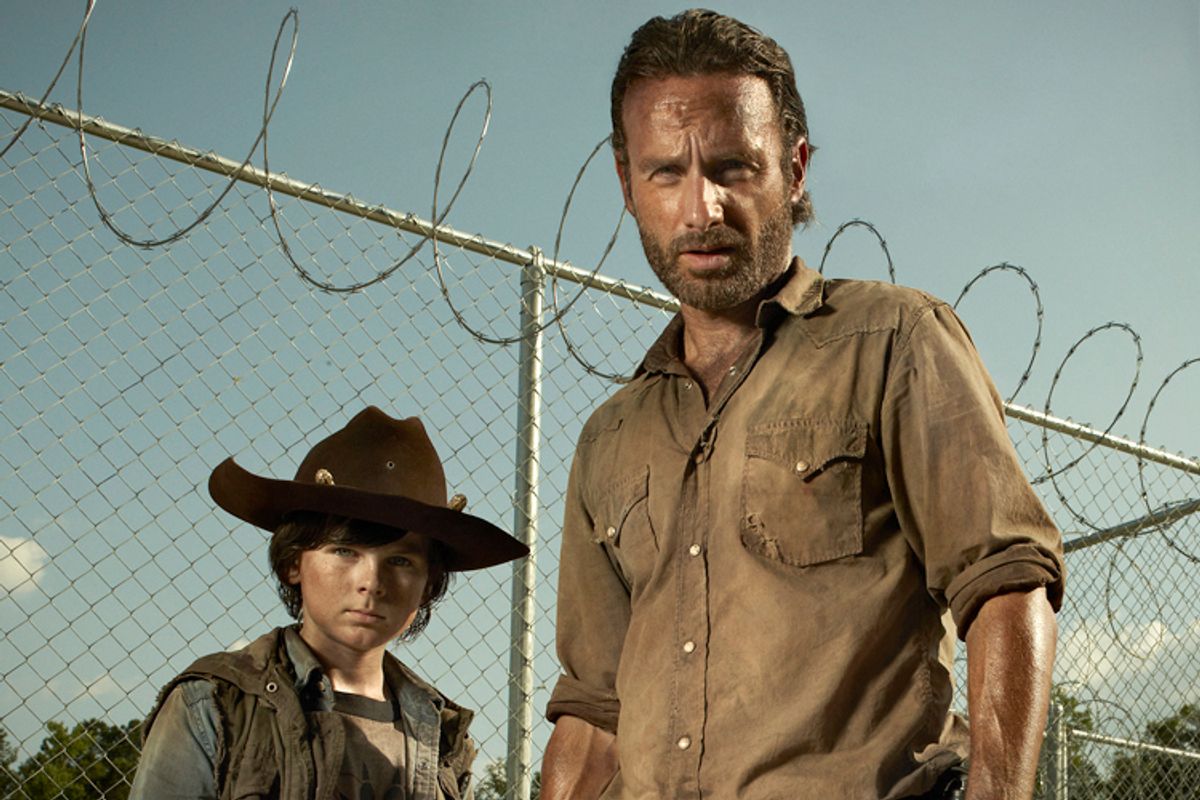

Near the end of season two of "The Walking Dead," Sheriff Rick Grimes had his masculinity challenged by his former best friend, Shane, when the two of them had their High Noon face-off in a field under a full moon. Shane told Rick that he had a broken woman and a weak son, that Rick wasn't man enough to take care of his family or to keep them safe, and that the best thing would be for Shane to kill Rick and assume leadership of the band of survivors of the zombie apocalypse. In the struggle, Rick killed Shane by stabbing him in the chest, but it was Carl, Rick's son, who shot Shane through the head when Shane "turned," and became a walker.

Season three ended last night with Rick once again being told that he wasn't man enough to keep the group safe. This time, his interlocutor was his son, Carl. Rick had confronted Carl because the boy had killed a young man who was attempting to surrender to Hershel and Carl, and Hershel had told Rick that Carl had gunned down the young man in cold blood.

"Hershel told me about the boy you shot," Rick said.

"He had a gun," Carl said.

"Was he handing it over?"

"He had just attacked us."

"Yeah. Yes he had. Was he handing it over?

"I couldn't take the chance," said Carl. "I didn't kill the walker that killed Dale. Look what happened."

"Son, that is not the same."

At which point, Carl opens up on his dad with both barrels. "You didn't kill Andrew and he came back and killed Mom. You were in a room with the governor, and you let him go. And then he killed Merle. I did what I had to do. Now go, so he doesn't kill any more of us."

Watching Carl order his father around did not come as a surprise to those of us who have watched Carl's growing toxic masculinity, which developed over season three. If season two left open the possibility that Carl was a child, season three asked us to believe that somehow, Carl has stepped into the shoes of a man, not only the possessor of a gun with which he is a crack shot, but also the person who is left to guard the adult women when the other men are off doing something else. Rick even consults Carl about whether Michonne should be allowed to stay with the group, and Rick seems to take seriously Carl's pronouncement that he thinks she's one of them.

(It is especially galling because, if we follow the time schedule of the show's world, only a year has passed since Carl was an eight-year old boy catching frogs with Shane. But the show has been on for three seasons, so the actor who plays Carl, born in 1999, clearly doesn't look nine.)

Carl has influence in the group because he possesses something that none of the women on the show possess: a pair of testicles. For those of us who had hoped that season three of "The Walking Dead" would move beyond the white patriarchy of the first two seasons, we have been disappointed.

If anything, gender and race have become even more problematic in this past season than they were in seasons one and two. Where before, I argued that in this new world, women were to be protected while men of color occupied a liminal space, it now appears that the white men have closed ranks and cemented their power. Women have been taught to shoot guns so that they can participate in protecting the group, but they do not have access to power — they are not consulted when major decisions get made — and their bodies have become the sites of contestation for men's power.

And race? Race has become a mess — an offensive mess — where African-American men have become interchangeable, replaceable parts and where Glenn, who is Asian-American, suffered the ignominy of being tortured into giving up valuable information about the group and who was rendered helpless to protect his girlfriend, Maggie, from being sexually assaulted. While it was Maggie who was sexually assaulted, the writers made the sexual assault all about Glenn — his failure to protect Maggie, his anger that this had happened to her — to the point where he was unable to offer to her the comfort she sought from him. His shame overrode her need for help recovering from what had happened to her.

At the end of season two, those of us who had been waiting to see the domestic reordering of the sexes finally come to an end were relieved to see the arrival of Michonne, a tall, powerful, African-American woman, armed with a katana, who saved Andrea from death. Except, as my colleague, Noelle Paley, pointed out to me in conversation, Michonne exemplifies one of the ugly stereotypes about African-American women. Michonne has two male walkers in chains — African-American males — whom she has neutralized by removing their jaws and their arms. These black male walkers have been disempowered — ritually castrated, if you will — by a black woman, which is itself an ugly stereotype: African-American women, it is argued, disempower their own men. And while the writers of the TV show may not have been thinking of this particular representation of black women, it further points out the writers' blind spots toward race and gender.

When Michonne shows up at the prison later in the season, she doesn't speak much. She grunts, in fact; she is rendered as near-animalistic. One might argue that she is the strong but silent type, but that's certainly not how she presents herself to Rick's group. She is treated like an outsider—everything about her screams outsider—not only her race and gender and the fact that she has been able to survive out in the zombie world without male assistance, but also because she wears dreads, and she carries a katana—not a gun—but rather, a long, phallic weapon that she wields better than any male. And when the group tries to make a decision about whether she will be allowed to stay among them, it is Carl—the kid—who is allowed to make the decision that she does fit in because he has witnessed her killing a lot of walkers.

But if Michonne is briefly accepted as one of them, in the next episode, Michonne's body becomes an object of barter. Rick and the governor are trying to negotiate a peace so that they don't wind up killing each other's group. (Yes. Humans are killing other humans while they should be killing walkers, but the two male leaders are fighting over territory — just as male animals do. Even though there's plenty of land, they're fighting for control of more land.) The governor tells Rick that the war can be circumvented if Rick agrees to one condition: "I want Michonne. Turn her over and this all goes away. Is she worth it? One woman? Worth all those lives in your prison? Is she?"

Rick asks the governor why he's wasting his time on a two-bit vendetta. (Michonne had killed the governor's walker daughter, Penny, and put out the governor's eye when he attempted to kill her back in Woodbury.) The governor's ostensible reason for wanting to kill Michonne, he tells his assistant, Milton, is because Michonne killed Penny, and that's all that matters.

But, I found myself wondering, did the writers not realize the situation they had set up? They had two white men using an African-American woman's body as currency. We did that for 300 years. It was called slavery. Did the writers really want to remind us that, in this world, a black woman's worth stems from her ability to be currency, something that can be bought or exchanged in order to stop a war? And these are two Southern men.

My partner turned to me and said, "Where did the writers get the idea that it was okay to use that as currency to buy our [the viewers'] outrage? It's offensive. How did this all of a sudden become something you could do in a plot? She uses a katana. She has dreadlocks. She's an Other. Why does this become a token of currency and what does it say about how we [the viewers] feel about others?"

Why indeed? The writers made the choice to turn Michonne's body into currency, and then dare to frame the entire argument that takes place between the governor and Rick as being about whether it's okay to sacrifice one person to save the rest. When, in reality, what they're arguing about is whether Michonne's body is property enough to settle a debt.

When Rick returns to the prison, he chooses to talk to the following people about whether he should go through with the decision to turn over Michonne. Hershel. Daryl. And Merle. Merle — who beat up Glenn and took Maggie to the governor — Merle, who has functioned previously as the person where all of the show's racial problems are located. Rick doesn't talk to Glenn. And he doesn't ask a single woman in the group. Merle refers to the group that Rick does talk to as "the inner circle." That it doesn't matter how awful a person Merle is, Rick will still consult him rather than consult the group about this awful decision. It doesn't matter that Carol and Maggie have become crack shots who are capable of defending the group from the walkers; they don't have any power. They don't have any power because they don't get to make any decisions.

At the beginning of season three, over in Woodbury, Michonne and Andrea had been captured by the governor's mercenaries. Michonne had sensed right from the start that something wasn't right in Woodbury. But Andrea — Andrea the civil rights attorney who survived the winter with Michonne without aid from any men, Andrea who can handle both a gun and a knife to defend herself from walkers — we know right in that first episode that Andrea has set her sights on the governor. Just as she had done with Shane, Andrea looks for a way to get power through sleeping with the male power in the group. In Woodbury, that's the governor. And it only takes a few episodes before Andrea is sleeping in the governor's bed. When Michonne presses Andrea to leave, Andrea refuses, and Michonne is thrown out of the village with Merle chasing her, trying to kill her. Merle loses Michonne, and he kills his own men instead to make Michonne look guilty. He chases Michonne into a small town where he encounters Maggie and Glenn, who are scavenging for baby formula for baby Judith, the baby that Lori had died giving birth to. (Lori made the ultimate sacrifice — dying in childbirth — and that redeemed her after two seasons of being the show's Lady Macbeth and general pain in the ass.)

Merle captures the two of them — he gets Glenn to surrender when he puts a knife to Maggie's throat — and takes the two of them back to the village. Merle, who knew both Glenn and Andrea from the original group back in season one, does not tell Andrea that Glenn is in the camp. Instead, he beats Glenn senseless and encloses Glenn in a room with a walker, all in an attempt to get the information about where Rick's group (and therefore, Daryl, Merle's brother) are hiding out. And yet, Glenn won't give up the information.

Maggie's body, again, a woman's body, becomes the site of contestation. The governor makes Maggie strip and stand before him topless, and he throws her over a table with the intent to rape her, but then changes his mind and takes the half-naked Maggie to Glenn to show the young man the power that the governor has. "You are powerless," he seems to be saying. "You can't protect your woman and now, I'm about to sexually assault her in front of you." It's at that point that Glenn gives up the group's location. He does it to save Maggie, and sure enough, once the governor and Merle have the information about the prison, they leave the two of them alone.

Glenn is made weak by his love for Maggie. It is a theme that Glenn will return to later in the season, when he tells Daryl that Glenn can't forgive Merle, even though Merle has been accepted into Rick's group. Daryl tells Glenn he needs to forgive Merle. And Glenn responds, "He took Maggie to a man who terrorized and humiliated her. I care more about Maggie than I do about me."

Perhaps this is the reason that Glenn is excluded from the inner circle of men. We are to believe that Rick, Hersheland Daryl are driven by rational self-interest in keeping the entire group safe, possibly at the expense of sacrificing Michonne. But Glenn? Glenn's first loyalty is to Maggie — he proved it when he gave up the location of the prison to save Maggie; he cements that by telling Daryl that he can't forgive Merle for what he did to Maggie. Glenn is too soft. He always has been. Is it significant that Glenn is Asian-American? That, as the Other, his alliance is to the woman he loves? Is Glenn a man who is ruled by emotion rather than his intellect? It appears that the writers have written him this way.

If gender and Glenn's position as the Asian-American man who loves too much are problematic on "The Walking Dead," I'm not sure I even have the vocabulary to talk about the role of African-American men.

As I wrote about earlier in the season, T-Dog had identified his role, as the only African-American man, as precarious, a position that he had been told by Dale was ridiculous. I argued that it was not a matter of if, but when T-Dog would be killed. We got our answer early in season three, when T-Dog was killed at the moment that another African-American man, Oscar, one of the prisoners, was introduced into the group. It sounds overly cynical to argue that the writers seem to have made a decision that the critical mass of black men that can be in Rick's group is one—but then in examining what happened throughout the season, it doesn't appear cynical at all.

Andrew, the rogue (African-American) prisoner who Rick had assumed had been killed by walkers, wreaked his revenge on the group for casting him out by tearing down fences and laying down bait to lure walkers into the protected areas of the prison. In the chaos of running from the walkers, T-Dog is bitten, and then, with his last burst of strength, he leads Carol (a white woman) to safety. When they find themselves trapped in a hallway with walkers, T-Dog provides cover for Carol by throwing himself at the walkers, guaranteeing his death, but allowing Carol enough time to escape.

During the fight with the walkers and the rogue Andrew, however, the other African-American prisoner, Oscar, comes to Rick's aid and kills Andrew, thus allowing Oscar into the group. So the group loses an African-American man, but gains the one they lost by getting Oscar. (If it sounds as if I'm saying that African-American men are exchangeable on the show, that's because that's how it appears.) When Tyreese and his sister, Sasha, both African-American show up a few episodes later, my friends and I began a cynical death watch for Oscar. And sure enough, Oscar is killed within an episode of Tyreese showing up. Tyreese now becomes the group's lone African-American, only this time, because Rick is now having hallucinations about his dead wife, Lori, Tyreese, Sasha, and the two white characters they showed up with are kicked out of the prison, and they head for the governor's village.

The writers' treatment of women and men of color cannot be blamed on the fact that the graphic novels were written this way, therefore they have to stay with the original story. No. Daryl, who has become a main character on the television show, was a one-off character in the graphic novels. In the graphic novels, it was Dale, not Hershel, who loses his leg. Tyreese has a major role in the graphic novels; so far his role on the show is negligible. And, gay characters? In the graphic novels the show is based on, there was a gay storyline. There's no sign of LGBTQ characters. The writers are making clear choices about a world where straight, white, and male is the optimum subjectivity.

The character of Milton might have been a way into a gay storyline. Milton does not fit the masculine stereotypes of brawny, good with a gun, a tough guy. Rather, Milton is an intellectual, a scientist, who believes that there is a spark of life left in the walkers, and who devotes his research to trying to find a way to revive a walker so that s/he will be a real person again. Milton is soft spoken and gentle, and tries to reason with the governor almost as if he were the governor's wife. He is the civilizing influence on the governor, the opposite of Merle, the governor's henchman, who would rather fight or kill than reason.

Milton's story arc is that during the season, he comes to realize that the governor is really a bad guy, and that if Milton looks away from what the governor is doing, that makes him a bad guy, too. So, in an act of heroism, Milton foils the governor's plan to use walkers to attack the prison. The governor punishes Milton brutally. The governor is keeping Andrea prisoner (after hunting her down when she tries to escape Woodbury), and he orders Milton to kill her inside the tiny room where Andrea is trussed to a chair. When Milton refuses, the governor stabs Milton and tells him that now he is going to die, and when he dies, he's going to turn. When he turns, the governor tells Milton, Milton will kill Andrea, so Milton's attempts to stand up to the governor have been for naught.

Milton dies, just as Andrea has figured out a way to wriggle free of the bonds the governor has left her in. When Rick, Hershel, Tyreese, and Michonne find Andrea, they find that she has killed Milton, but she has been bitten. And now Andrea's heroism comes to the fore. For three seasons, the writers have treated Andrea as almost a joke — a woman who thinks that when she learns to shoot, she'll be accepted as a leader. A woman who thinks that first by sleeping with Shane, and then later, by sleeping with the governor, she can gain power. But they also make Andrea weak. Even when it becomes clear to Andrea that the governor is not the gentle lover she thinks he is, even after she has met up with her friends at the prison and they have begged her to use her body to seduce the governor so that she might kill him as he sleeps, even when she has a moment when the governor is asleep and Andrea rises, naked from their bed to grab a knife, she can't go through with it. She can't kill the governor, and the governor goes on to kill again and again because of Andrea's failure of nerve. Andrea is too weak, we are led to believe, to kill the governor for the good of the group — and as if to prove how weak she is, Carl, the little boy, has no such reservations about killing in cold blood to save the group.

But now that she has been bitten, Andrea rises to heroic status. She doesn't want to put the burden of killing her on her friends. She asks, instead, for a gun so that she may shoot herself in the head. And she explains why she tried to intervene, to get Rick and the governor to negotiate with one another, even though the writers have made her look so naïve for trusting that the governor would come to Rick in good faith.

Michonne kneels next to the slumped Andrea. Rick and Daryl are in the room, too.

Andrea says, "I just didn't want anyone to die," she says as explanation for why she pushed so hard for a negotiated peace. And then she asks for Rick's gun. "I can do it myself. I have to. While I still can. Please. I know how the safety works."

Michonne says, "Well, I'm not going anywhere."

Andrea says, "I tried."

"You did. You did," says Rick.

And then the tough Daryl and Rick leave Andrea alone in the room with Michonne. They wait out in the hallway. We hear the gunshot. Andrea has killed herself, rather than put that burden on any of her friends. It is Andrea's redemption, just as the writers make Merle's self-sacrifice his redemption the episode prior.

There are many more incidents that I could have used to illustrate the point that the gender and racial politics of "The Walking Dead" are a problem for those of us who love the show, but who feel a great deal of frustration that the writers have excluded so much of their audience from feeling that they, too, could be among the survivors. And who seem to use symbols of past oppression without thinking about how loaded those signals are (Merle puts a hood over Michonne's head. Really? A hood? As they used to do when blacks were lynched?)

The writers have left us bread crumbs about next season. Carl will no doubt move even futher into the center of the show, as the toxic masculinity he has taken on will bring him in direct conflict with all, including his father and Hershel, who get in his way. The last image from the show last night was Carl's disapproving face as he surveyed the busload of survivors from Woodbury that Rick had brought back to the prison. Perhaps for all the fan complaints that Lori wouldn't let Carl grow up, it would have been better to follow her way and try to protect Carl from these matters that are beyond his ken for just a while longer. He reminds me now of the child soldiers who, at the age of 12 or 13, kill indiscriminately, and who turn into emotional zombies because they are not emotionally ready for what they have been forced to do.

The other bread crumbs are about Michonne and Tyreese. Will they be allowed to assume power within the group? Or will they remain the outsiders that they were all this season?

Rick has announced that he will no longer run the group as if it is his own fiefdom, but that he is putting the responsibility for the group back into the group's hands. Democracy has returned, but again, who is going to get a vote?

It is not insignificant that the writers killed off the two most polarizing women on the show: Lori and Andrea, leaving behind women who know how to get along. But what of Michonne? Will she be given good writing? Or will she become the object of hatred on fan sites?

Having been fooled by the promise of the team of Andrea and Michonne to create new gender relations during season three, I now wonder where the writers intend to take us in season four. Maybe, this time, we will see the breakdown of the white patriarchy. But I'm skeptical. I'll keep watching — of course, because I love the show — but with the cynical eye that the writers have worked to instill in those of us who believe that a post-apocalyptic world does not have to be one in which we are all reduced to our animal instincts or we don't survive.

Shares