When approaching the world’s hottest chile pepper, caution seems wise. “Be careful,” says San Diego-based chile grower Jim Duffy, who mailed me a sample of the Moruga Scorpion, which he is trying to get in the Guinness Book of World Records for its insane level of heat. Duffy isn’t kidding around: upon popping the Scorpion into my mouth, the tip of my tongue feels like it’s being jabbed by a hundred needles and there’s a heavy burn rolling toward my tonsils. My salivary glands are in overdrive, drool gushes into my mouth and my nose is running.

When approaching the world’s hottest chile pepper, caution seems wise. “Be careful,” says San Diego-based chile grower Jim Duffy, who mailed me a sample of the Moruga Scorpion, which he is trying to get in the Guinness Book of World Records for its insane level of heat. Duffy isn’t kidding around: upon popping the Scorpion into my mouth, the tip of my tongue feels like it’s being jabbed by a hundred needles and there’s a heavy burn rolling toward my tonsils. My salivary glands are in overdrive, drool gushes into my mouth and my nose is running.

This all from eating a piece the size of a sesame seed.

The Moruga Scorpion, a squat, reddish-orange chile with a perky tail, like a stinger, is over 300 times hotter than a jalapeño. It is one of a new class of chiles called “Superhots” that are, as the name implies, way, way hotter than most hot peppers.

With wicked-sounding names like the Ghost Pepper and the Carolina Reaper, they are crossbreeds of peppers that have been grown traditionally in India and Trinidad but were virtually unknown in the U.S. until recently. However, with hot sauce just behind social gaming and solar panel manufacturing as one of our fastest growing industries, Superhots have been, not surprisingly, discovered in the past few years. The Internet helped. A 2010 story about the Indian government using the Ghost Pepper to make a tear gas hand grenade was picked up everywhere, and soon after, Superhots became the Kopi Luwak of the chile world: highly sought after and considered to be the primo shit.

“It used to be the habanero was the hottest thing around,” says Mike Hultquist, a chile blogger and cookbook author who’s developed over 100 recipes for jalapeño poppers. “Now it’s all about the Superhots.”

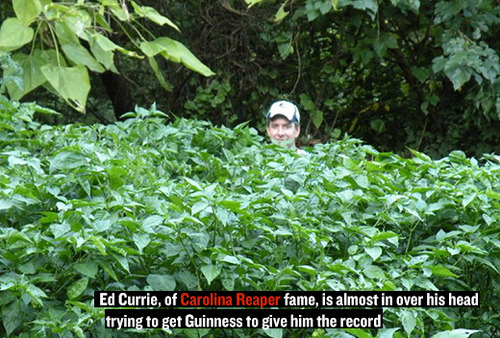

“I’ve just accepted that I’ll have to pay over $19,000 to get the record,” says Currie, who has put his pepper through rigorous, expensive lab tests, to convince Guinness. “I’m in too deep at this point to stop now.”

“I’ve just accepted that I’ll have to pay over $19,000 to get the record,” says Currie, who has put his pepper through rigorous, expensive lab tests, to convince Guinness. “I’m in too deep at this point to stop now.”

There’s a serious commercial advantage to being the official grower of the official hottest pepper in the world. Superhot seeds aren’t commercially available from large seed companies, so heat freaks wishing to grow their own have to buy them online from small suppliers like Duffy and Currie. Being able to market yourself as the record holder is great advertising. Hot sauce makers, who generally contract with one main grower, sell more sauce with a world-famous chile on the label.

“The Superhot peppers are an extremely valuable commodity,” says Dave DeWitt, an author and chile expert who runs the industry’s biggest event, The National Fiery Foods and Barbecue Show in Albuquerque, New Mexico. A typical Scorpion pepper pod at a farmers’ market will go for one dollar, notes DeWitt. “Think if you had an acre of these things; think how much money you could generate. Behind marijuana, they have the potential to become the second- or third-highest yielding crop per acre monetarily.”

Superhots might be a “thing” now but extreme hot pepper fans, dubbed “Chileheads,” have existed for decades. These are people obsessed with hot food, who add hot sauce to everything from spaghetti sauce to coffee, vying to see who can go hotter. They make pilgrimages to hot sauce conventions. Post reviews of spicy caramel sauce and ghost pepper barbecue sauce on their blogs. Share schematics of hydroponic chile “grow boxes.”

Ed Currie of Carolina Reaper fame started growing Superhots in the 1980s, after reading about them in an old National Geographic article and tracking down seeds via letter. Butch Taylor, current Guinness Record holder, got his seeds through a private MSN forum he belonged to throughout the 1990s.

Chiles are perennials and can live from year to year, producing fruit. The more arid the temperature, the more the plant is stressed, and the hotter the fruit it bears. Paul Bosland, director of The Chile Pepper Institute, a research institute within New Mexico State University, describes Chileheads’ relationships with their plants as anthropomorphic.

“We have members who give them a name, like Fred or Peter, and grow very attached,” he says. “When they die, they mourn.”

Ted Barrus, aka “Ted the Fire Breathing Idiot,” is one of a growing number of chileheads who make YouTube videos of themselves eating entire raw Superhots, then recording their reactions. A cross between Jackass and a video of somebody having a bad acid trip, Barrus wretches, eyes red, and in extreme pain moans things like: “It feels like an atomic bomb in my stomach now!”

Nonetheless, Barrus tells me that through his “roller coaster of pain” there is a “massive endorphin rush” that keeps him coming back for more.

“I’ll give you my personal opinion for why Superhots are so popular right now,” says Currie. “Drug addiction.”

He may be right. When the chemical compound capsaicin comes in contact with mucous membranes, the body releases endorphins to counteract the pain. Chileheads describe feeling something akin to runner’s high.

“They don’t get physically addicted to chile peppers as much as they get psychologically addicted,” says DeWitt. “That’s why so many people carry something with them at all times—mini bottles of hot sauce, what have you.” DeWitt recently received a gift from a Chilehead friend in Italy, which included vials of chili pepper of ascending heat housed in a custom leather carrying case with snaps.

The subculture even has its own language: Chileheads speak in Scoville Heat Units, or Scovilles, as in: “At 3 million Scovilles, this sauce is nuclear!” The terminology has a curious history. In 1912, pharmacologist Wilbur Scoville tried to figure out how to make medicine with capsaicin in it palatable. He developed a test where he put capsaicin extract into a sugar water solution and kept adding more sugar water until human tasters could no longer perceive the heat. The resulting ratio of sugar water to capsaicin extract became the official measure of a particular chile’s heat, or its Scoville Heat Units (SHU.) (A pepper’s heat is now tested via high performance liquid chromotology, but is, curiously, then converted back to Scoville Heat Units.)

But if capsaicin really was a drug, Chileheads would all be mainlining pure C, and they’re not. (They could if they wanted: there are products on the market like The Source—bottled pure liquid capsaicin that comes with its own Indiana Jones-esque display case. At 7.1 million Scoville Units, the extract is over six times hotter than the hottest peppers grown by guys like Duffy.)

But if capsaicin really was a drug, Chileheads would all be mainlining pure C, and they’re not. (They could if they wanted: there are products on the market like The Source—bottled pure liquid capsaicin that comes with its own Indiana Jones-esque display case. At 7.1 million Scoville Units, the extract is over six times hotter than the hottest peppers grown by guys like Duffy.)

The thing is, all heat is not created equal. Bosland, of the New Mexico Chili Institute, has identified 22 related alkaloids that give the sensation of heat, and each one reacts differently in the human mouth producing a different, for lack of a better word, high.

“How fast does the heat come on? Instant or delayed? How long does it linger? Minutes, or hours? Where on the mouth do you feel it? Tip of your lips, mid-palate, throat? Is the heat sharp like pins sticking you, or flat like someone is painting the heat in your mouth?” says Bosland.

Hotsauce maker John “CaJohn” Hard, for instance, talks about the ghost chili “coming on” more slowly, versus the Scorpion’s attack as “instant” and “needle-like.”

Peoples’ reactions to various peppers are subjective. The number of receptors we have varies from person to person, which is why some can eat super hot food and others can hardly handle Taco Bell hot sauce. And yet, as a population, we are becoming overall more accustomed to spicy food. Check out your average college kids bellying up for a hangover brunch, and you’ll see them reaching for Sriracha, not ketchup.

“You never hear people say, ‘I’ve tried hot and spicy and now I’ve gone back to bland,’” says Hard. “They keep seeking hotter and hotter.”

And truth be told, after the drooling let up, and I’d gone on about my day, I couldn’t get the lingering memory of the Moruga Scorpion out of my head. Like that first cup of coffee in the morning, it woke me up and gave a certain sparkle to my day. I’m not ready to become “Ted the Fire Breathing Idiot” anytime soon, but I think he’s onto something. There’s pleasure in the pain. I might be a Chilehead after all.

Shares