Remember the car bomb at the State Department on Sept. 11, 2001?

Of course not -- there was no such thing. But amid the fear and chaos of that day, that was among the many rumors that spread quickly, making the early coverage of the day's tragedy seem all the more dramatic and upsetting.

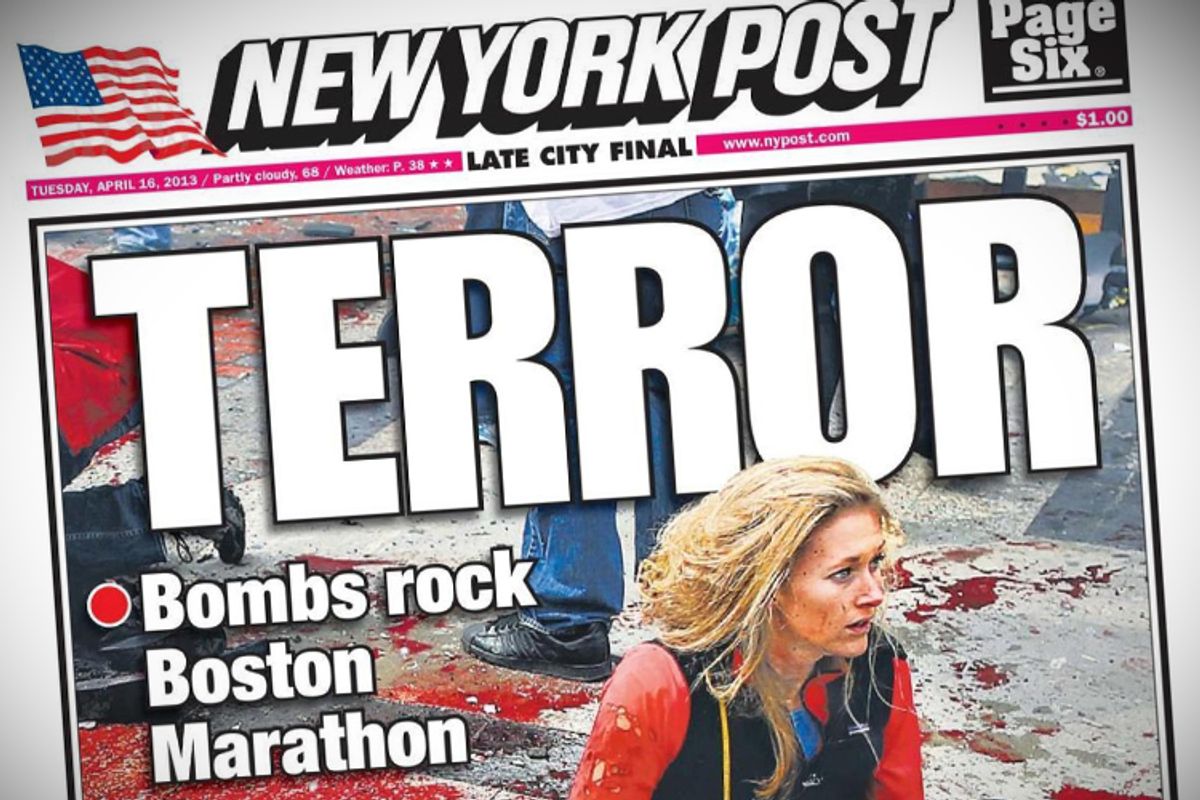

False information also spread yesterday. There was former congresswoman Jane Harman on CNN, warning of additional attacks because "A signature of al-Qaida is simultaneous attacks." Never mind that we still don't know who was behind the bombing. The New York Post cited 12, rather than the two deaths first confirmed by officials. And the question of just how many "unexploded devices" there were in the city of Boston hung over the day, as this Examiner piece extrapolating from a Bloomberg News tweet proves.

But to conflate fact with fiction in moments of extreme tension is not a bizarre reaction, say writers who have studied the psychology of fear. It is, in fact, what makes us human.

"The human brain is a machine for making sense of the world," said Daniel Gardner, the author of "The Science of Fear: How the Culture of Fear Manipulates Your Brain," a psychological examination of alarm and anxiety. "It is absolutely compulsive about doing that, particularly about making sense of shocking events. We are compulsive about making sense of things. That process happens automatically and effortlessly; we create explanatory stories as easily as we breathe."

And in the case of extreme or shocking new information that doesn't jibe with the way we understand the world -- airplanes destroying skyscrapers, a bomb ripping through the final leg of a marathon -- our brains go into overdrive to connect details into a rational story, even if it's one that's counterfactual. As Jeff Wise, the author of "Extreme Fear: The Science of Your Mind in Danger," put it: "Information that points to potential danger becomes more salient when you're under threat. If you're a soldier under threat on sentry duty, you're much more likely to hear that twig snapping. People that feel under threat are more likely to pay attention to information that puts them in danger."

Wise pointed to a phenomenon known as "fear-potentiated startle," a manner of measuring fear in animals; the more afraid the animal is, the more fervidly it will react to a loud noise.

"When you're really scared, the prefrontal cortex shuts down. Emotion shuts down reason. You can't add three-digit numbers together on a roller coaster. It's difficult to be fully rational when you live in a world where information is incomplete. You have to make these rule of thumb leaps and guesses and you take a lot of mental leaps when you're under an emotional load like this. A lot of what seems irrational isn't. They're just decisions made under incomplete information."

The mind reverts, under strain, to simple prejudices and leaps: Bombing equals Islamist terror, for instance, or vague non-statements from a besieged Boston Police force equals many more unexploded bombs. Said Gardner: "Any information that seems to confirm our understanding of what just happened, we grab on it and won't ask if it makes sense or if it's verified. Information that contradicts our explanatory story, we won't look for that -- and if someone shoves it under our nose, we'll ignore it."

And everyone's individual understanding is different -- from those, like radio host Alex Jones, who believe that the bombings in Boston were a "false flag" attack to sow discord, or those who automatically blame al-Qaida. Gardner cited the 2011 massacre in Norway, committed by Norwegian national Anders Brevik. "People said, 'It's Islamist terrorists.' And that's a reasonable hypothesis. But a reasonable hypothesis is very different from a conclusion. A reasonable hypothesis is very different from a conclusion -- and if you leap to that conclusion, you can come to other unhelpful conclusions -- like that there's an immigration problem." (Indeed, Rep. Steve King has made that claim today.)

But even that illogic makes a strange sense, says David Altheide, a sociologist at Arizona State University and the author of "Creating Fear: News and the Construction of Crisis."

"We have this sense of who our enemies are and we always seem to explain current and future events based on the past," Altheide told Salon. "There's a logic to that. [...] If our narrative is borne out, then that makes people feel more secure in their view of the world. That's why people seek out counterfactuals that are consistent with a dominant narrative."

The boldest claims about yesterday's events have largely been walked back as more facts have become clear. Yet the days ahead, until a culprit is named, remain rich with possibility for wild claims. According to Gardner, left- and right-wing political interpretations of tragedy aren't attempts to politicize the tragedy but divergent interpretations by two different mind-sets trying to cross a wilderness of uncertainty. "Look at people's instant explanations. The explanations they offer fit perfectly with their ideological commitments," he said.

"Uncertainty is unacceptable to the human brain. You're going to fill in that gap somehow. But we have to recognize that and just shut up."

Shares