RIGHT NOW ON the Bowery you can step into a time machine. It will carry you back to 1993 or thereabouts. It spreads over five floors in a great gleaming building, and to first acclimate you, a line of boxy Samsung televisions broadcast highlights from the year. This was before TVs were flat-screen or LCD or HD, when the initials that stood for high-tech – or any tech – in home entertainment were VHS. Here was a moment before the Internet was big, the World Wide Web did not exist yet (not really), AIDS was still “uncured,” Clinton had just been inaugurated, and it was a watershed moment for art.

RIGHT NOW ON the Bowery you can step into a time machine. It will carry you back to 1993 or thereabouts. It spreads over five floors in a great gleaming building, and to first acclimate you, a line of boxy Samsung televisions broadcast highlights from the year. This was before TVs were flat-screen or LCD or HD, when the initials that stood for high-tech – or any tech – in home entertainment were VHS. Here was a moment before the Internet was big, the World Wide Web did not exist yet (not really), AIDS was still “uncured,” Clinton had just been inaugurated, and it was a watershed moment for art.

This five-story teleportation device is an exhibit at the New Museum called “NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set Trash and No Star.” Ignore the subtitle. It’s from a Sonic Youth album that doesn’t appear in the show and was, in fact, released in 1994. Though, I’ve read some pretty baroque interpretations of why it fits with such a close textual analysis they veer on New Criticism.

The show has in it work that responds to the culture wars. There’s art about sex and gender, pieces that are funny and angry, but interestingly not ironic. When did we get irony and why? This was an age of agitation and protest — of ACT UP and the Lesbian Avengers. Dykes marched. Nights were taken back. There were “lipstick lesbians.” Madonna made a play at being one. Her book “Sex” came out. Art expressed this moment with work about “identity,” and politics was central to art as were theoretical critiques of the institutions where it appeared.

Then it all disappeared.

But, it seems as if that early '90s moment was prophetic, or, at least, is timely today. It was referred to in countless reviews of last year’s Whitney Biennial, and not just because the same woman was in charge of the '93 and 2012 installments, but as if something from that moment has informed the present.

This new 1993 show at the New Museum is, in part, to mark the 20th anniversary of that earlier exhibition, which was the most reviled Biennial ever, itself quite an achievement. Take-downs of the survey are blood sport in the art world, and that year’s was criticized from the National Review to the New York Times. The usually eloquent and nuanced Peter Schjeldahl, writing in the Village Voice, hated it. The New York Times' head critic actually wrote, “I hate the show,” and the New Yorker turned the exhibition into a “Shouts and Murmurs” sketch.

You can forgive the curator Elizabeth Sussman for grinning uncomfortably in a video about the 2012 Biennial as she talks about the response in 1993. Now, however, that year, that show, is back on people’s minds. It’s been on mine for months, maybe since that Biennial, maybe since reading the reviews, but I think there’s something more going on.

I think of this as a mystery. It feels like a moment that the lights went out and everything was gone, as if one second it was here, and the next – disappeared. Curtain dropped. Game over. The thing, of course, with movements and moments is that they’re never that clear. The lines of beginnings and endings aren’t defined, but the critical response was so negative that considering the 1993 Whitney Biennial now, it seems like it marked the end. Or, caused it.

So, why? What happened?

The work was too exposed, too raw and personal. It was confessional and diaristic, with things that look, in our age of reality TV and blogs, prescient. Or, banal. This was still an era of cable access and "Wayne’s World" — where 19-year-old Sadie Benning made a swooning semi-fictional Pixelvision self portrait, while Karen Kilimnik’s clumsy edits of "Heathers" reshuffle the movie to give it a million different meanings. The end result is six hours long.

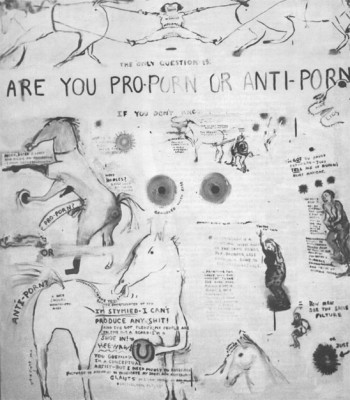

Explicit (see “exposed,” above). Just a different sort of exposure. Physical. Exhibit A here would be Sue Williams’ plastic puke on the Whitney’s polished floors, half, it seems to me now, like something from a joke store in the mall and half rage at eating disorders and sexual violence. The puke puddle was accompanied by a painting currently in the New Museum: “Are You Pro or Anti Porn?” which staked out the lines for feminists in the '90s. In the piece she scratches out and scrawls over words with barbed questions and pointed remarks. The very technique seemed angry, vengeful even.

Race. Sometimes I think the disappearance was, partly, thanks to latent racism. Work at the time often addressed racism head on, and I wonder if people didn’t want to be confronted by it. Then again Hilton Kramer, a conservative critic indeed, was at the New York Post and not yet the New York Observer when he wrote of one of the curators: “There is a certain awful logic in having Ms. Golden on the curatorial team.” This was about Thelma Golden, the one black curator of the Biennial, one of the few black curators in New York at the time, and now one of the city’s most respected museum directors ….

Or, Sexism. That Biennial included more women than ever, and still there was a backlash from other women – like New York magazine’s Kay Larson. She wrote in a comment about Jeanine Antoni’s piece “Gnaw” (still my favorite work from that show): “You need to know that women resented minimalism’s formal perfection because it allowed them no space for their private lives.” Really? We’re dissed because we need to express our private lives? How regressive. That reminds me of those dictates about how women authors should only write domestic novels.

Antoni’s installation was eloquent and pointed. She took 600-pound cubes of chocolate and lard and gnawed at them – teeth marks visible still. Yes, this was a comment on minimalism, revisited with a feminist take. She then took that masticated lard and turned it into 400 tubes of lipstick. The piece was also a play on the body art of the early 1970s and the extreme performance work of people like Gina Pane who carved makeup into her face. With critics like Larson, no wonder Elizabeth Sussman is there in the video on the Whitney’s website wincing now.

At the time Liz Kotz wrote in a review in Art Forum (quoted in the catalogue for “NYC 1993”) about how artists – non-white, non-male, non-straight artists – had been asked since the 1980s to make work about their identity as price of admission to the art world. “Critical work of the past decade has endlessly interrogated the commodification of identity politics in which producers, whether black, Chicano, Asian or gay are expected to offer up their identity, their ‘difference,’ for the consumption of … the viewing public.” Her point is fair. Who wants to be defined constantly by their identity? As if the only way to get invited in you have to make a show of what sets you apart? It’s the distinction between being a man or a black man, and the demand itself can start to smack of racism or sexism.

Certainly for many critics the work was too activist, too angry. But it also had a comedy to it like David Hammons’ hacked off sweatshirt hood. Called “In The Hood,” it’s both a one-liner and full of rage, veering from how people romanticized the ghetto to commenting on black lynchings. I’d forgotten the humor. Maybe everyone else did too. Maybe all we saw was the fury. Or, maybe it’s only funny 20 years on? Equally possible: I was just too serious to see it back then. I was in my early 20s. I remember a naïveté and fierceness (and not just my own) in rage, in staking outsomething. Something that meant something. If this were the early '90s and the art world, that “something” would have been “staking out the margins.” It would have also included words like “mimesis” and “alterity” and “transgression.”

David Hammons, In the Hood, 1993. Athletic sweatshirt hood with wire, 23 x 10 x 5 in (58.4 x 25.4 x 12.7 cm). Courtesy Tilton Gallery, New York

The most complimentary review of the '93 Biennial was Roberta Smith’s in the New York Times. She called the show “arid.” She also called it a “watershed.” (She was not the one at the Times who “hated” it.)

Then, the market shifted. 1993 was still a recession, but as art markets changed, and art fairs started to pop up and come to prominence that brought a different focus on a different kind of work. Angry work isn’t so easy to sell. Take work that you might be uncomfortable hanging in your living room? Work with a joke that could be on you? Work that might make you feel a tad guilty?

All this is slippery. It’s easy with hindsight to have neat boundaries, but the lines are messy. Things continue. Epochs and eras don’t start or end so simply.

All that fighting in late '80s and early '90s was exhausting too. The marching, the screaming, the protests … They sap you. So had the perpetual cycle of mourning New York was in with AIDS. The disease devastated the city, killing more men and women between 21 and 44 than anything else at the time. ACT UP was splintering. There was no cure. Not even any kind of half-successful treatment.

I’ve been asking people who were also around the city then about what happened. Ira Silverberg, now the NEA’s head of literature but at the time editor of the edgy genre-bending anthology High Risk, said, “1993 was the end of an era. It was still a holdover from the '80s, and as Simon Reynolds says, each new decade clings to the last. The East Village was gentrified, and the culture wars for many had been exhausted.” An artist in the New Museum show, Marlene McCarty points out, “Clinton was elected. The enemy wasn’t so clear anymore.” Also, the city changed. That year Giuliani was elected; the economy started to rebound. Wired magazine was launched. The Internet and tech boom were about to happen, and that money spread all the way from the West Coast to the East.

Melanie Fallon, a writer who’d just graduated college and was part of the Lesbian Avengers, explains that New York’s creative class got jobs – and money – with work in advertising and web startups. “Money won. The possibility of buying your apartment – the NEED to buy as rents skyrocketed – won. After the years of recession there were suddenly jobs that hadn’t existed before for many artists and activists. Not just in advertising, but at non-profits that grew from AIDS and other activism; and in academia with the explosion of MFA, cultural studies and creative programs.” She also says something achingly beautiful about the city all those years ago. “New York felt more queer then, and because of groups like ACT UP and the Lesbian Avengers and sex as politics, it had an erotic feel that was still very alive.”

~

I keep thinking of Sussman’s smile. I watch her over and over. Her voice rises and throat catches. I see something I recognize in that anguished grin. It haunts me, her words too and that nervous laugh. There’s something as well in her librarian glasses, and I think she never expected to be on the wrong side. In her laughter, she tries to shake off the controversy, to say, get along, move along, there’s not thing see here. And, she will say she is happy to have engaged the debate and touched a nerve, to be of critical importance in issues that resonated for the nation, that still resonate. But, but … In that very word is an unspoken qualification waiting to be made. Something more is concealed in that grin. I email a critic who wrote frequently for Art Forum at the time to ask what she remembers, and she says, “The whole idea of seeing this period we lived through turned into something historical is, well, very complicated. For me, it all seems so messy and unresolved, and I can’t say it’s become a whole lot clearer in 20 years.”

Somewhere between the angry critical response and that uncomfortable grin, there’s an answer, and maybe it’s big enough to explain the larger cultural shift. Or, maybe it just holds some answers for me. I want them though, personally, that is.

Back in 1993, I was pregnant and a stripper and a Helena Rubenstein Fellow in the Whitney Museum of Art’s Independent Study Program, from which young artists and curators are expected to emerge into the art world’s embrace. Those three facts – pregnant, stripper, art world – seem symbolic both of who I was but also a moment when politics and sex, porn and sex work and what side of feminism you were on were urgently important. I helped curate a show at the museum, and then I basically vanished, at least, from the art world. That was the year I decided I’d had enough of art, or if not art, of an environment that deemed itself “the art world,” as if it were set aside from the everyday world. I didn’t see a future there. It seemed small and as if it were preaching to the converted — though actually looking at the New Museum show, I can see how much art mattered. Just take the culture wars, and clearly art was having a national conversation.

But, walking through the exhibition, I’m haunted by this ghost of my past. I feel like I was stoned back in '93 and am dizzy now, or else having some kind of flashback. Hazy memories of names and places and pieces float back to me, though “float” might be too sweet a word to describe how it all feels. It’s a bit like that gasp of pain when an old boyfriend pops up in a place you don’t expect to see him, and you’re still raw. Then, he tells you that you did really matter to him and he misses you still.

I don’t think I’m the only one with this response to the show. Simon Taylor was another fellow in the Whitney Program, and his essay for the exhibit he curated that year is included now in the New Museum’s catalog. He writes on his web site about how the show has dogged him personally for 20 years and of his shock when the New Museum wanted to republish his work. Another friend, a photographer who’s made work about black gay identity that was back then largely centered on self portraits, did an installation for the New Museum that year. Seeing that work highlighted again, is “intense,” he says. Simon left the art world to open a bookstore in Santa Monica dedicated to art books; the other friend spends much time in Africa. We’re hardly the only ones who’ve slipped to the sidelines. Feminist painter Rochelle Feinstein, chair of Yale’s MFA in painting often has her students read reviews of the 1993 shows as object lessons in the art world’s fickleness. Only now many of those artists that looked like footnotes to history are making a comeback.

~

In the New Museum are pieces I’d helped choose and hang for that show at the Whitney, an exhibition that makes me uncomfortable to think of even today. The New York Times dismissed it as doctrinaire, but here, the little wall placards are saying it mattered.

That exhibit was “The Subject Of Rape,” and a piece from it that seems apt even today is included in “NYC 1993.” Conceptual artist Lutz Bacher took William Kennedy Smith grimacing on Court TV as he says, “I did have my penis” and turned it into an installation. The phrase and frown repeat over and over. Smith speaks endlessly about his penis; the local station graphics are still on screen. Nothing is made slick. After running through the loop, the video ends with his saying, “In her mouth.” The piece also came with a box of documents, which like Antoni’s “Gnaw” is revisionist minimalism. This cube, though, is rain damaged from sitting on Bacher’s Berkeley, Calif., porch. Inside the carton: photocopies of all the women’s depositions attesting – under oath and the penalty of perjury– to Kennedy Smith’s violence. Now, after the penultimate episode of "Girls" last month, the work seems timely still. Again. Too bad the box of documents isn’t at the New Museum.

There are many great pieces in the show like Pepón Osorio’s staged murder scene. A former social worker turned artist, he went out with detectives on the NYPD, and here the viewer, that is you and I, walk in on a scene with police-line tape as if the installation were hyperreal. A woman is dead on the floor. With its Puerto Rican flags and shattered Virgin Mary statuettes, the place looks like many of the apartments in my building on the Lower East Side where a woman was raped while I lived there. On another floor Kristin Oppenheim chants a capella, “sail on sailor,” a single line from a Beach Boys’ song as if intoning sadness and death.

There is work that is harrowing, humorous, monumental and sad. Much of it deals with AIDS. Perhaps the most moving piece is one I’d never seen by Nari Ward. It was shown once in 1993 in an old firehouse in Harlem, made from some 300 strollers strapped together. All were found abandoned on the street. The installation is a metaphor for the homeless and the city, children and hope and slavery. The strollers are shaped into an ark and tied together like slave cargo – also as if each is interdependent on the other. Over it all Mahalia Jackson sings “Amazing Grace.” The hymn, written originally in protest of slavery, gives the installation its name. For five minutes alone with this piece, you should go see the show. Ward’s installation has everything that makes art powerful – complexity, nuance and the ability to move the viewer …

Even the straight white guys in the exhibit are performing identity of sorts. “Bad Boy art,” it was called at the time as if some dark masculinity were laid bare in the work, like Jason Rhoades’ installation "Garage Renovation New York (Cherry Makita)." It re-creates a den handmade and remade with duct tape, cardboard and tin foil as well as actual drills and a pinup calendar. "Cherry Makita" is an antiheroic portrait of guy culture, showing all its seams and frailty and failures. Part of why I worked as a stripper was to learn what men did when they felt they’d slipped free from the daytime world and its upright morals. I thought catching men when they thought they were unobserved I’d uncover what manhood was about, as if some secret might be exposed. I did learn secrets about marriages and wives, jobs, divorces and children. I even had a customer who was still in the closet as if coming to a topless bar provided him some cover of normalcy. I just didn’t discover what I was looking for. And, looking at the installations now, there’s another resonance. Two of the four “Bad Boys” are dead, Rhoades of drug-related heart failure in 2006; Mike Kelley committed suicide last year.

Installation view of Jason Rhoades, Garage Renovation New York (Cherry Makita). Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Benoit Pailley

Here in the gallery I feel like I’m spying on my past, with that same smile, that discomfort, and the way that year was kept in, held in, held together and held back by the smile. What does a grin reveal? Or hide, or try to? Sussman shakes her head tersely; a guy in a strip club tells me to smile, I’m prettier when I do. I giggle in response … That smile, my anguished grin, is strongest standing before Sue Williams’ painting. My ribs are tight, chest clutched and face flushed, and I feel like I’ve been thrown back into ‘93 when I first saw the painting. I was angry then as if it were implicating me. The very question, “pro or anti porn?” is all it takes. Obviously as a stripper (a “sex worker,” as it was called then) I wasn’t neutral in that debate. I’m still not, and I still don’t blame porn, and here what I don’t see, not until I return the next day because I am too busy holding that uncomfortable grin, is the funny with Williams’ fury. The painting is dirty and filthy and comic, and as a woman to take all that and make something both angry and ribald is pretty transgressive (to use a good 1993 phrase) even if it came with a puddle of plastic puke.

Williams went on to fit into that next moment coming in the art world. She lost the rage and the humor but kept her surface relationship to comics, while Karen Kilimnik’s take on "Heathers" with its cable-access shonkiness moved on to become pretty paintings of girls and pop culture as if not quite sure on what side of obsession and criticality she wanted to be on.

Andres Serrano, Infectious Pneumonia, from “The Morgue,” 1992. Cibachrome print, silicone, Plexiglas, and wood frame, 49 1/2 x 60 in (125.7 x 154.5 cm). Copyright Andres Serrano. Courtesy Edward Tyler Nahem Fine Art, New York

The show makes this shift clear in one room. Andres Serrano’s morgue photos of people who died of AIDS hang across from John Currin’s painting of women in hospital beds, all big eyes and wan faces, as if stylized Victorian consumptives. The division between the two is stark as if the Serranos’ piercing meaning has been dulled and drained off with Currin’s pretty but essentially vacuous paintings. Part of me thinks that 1993 moment disappeared because it was all too much, putting that kind of anger and mourning in each piece. And like Liz Kotz said, so too is the responsibility of performing identity all the time, or being all too exposed, like Kiki Smith’s “Virgin Mary,” a visceral, eviscerated self-portrait with the muscles and tendons and sinews laid bare. Also, why shouldn’t an artist move on? Maybe Sue Williams genuinely did? Don’t we all have that right?

So, why look back now? Culture seems to move in 20-year cycles. The 2012 Biennial hearkened back to the '93 one, and back then I remember seeing Jeanine Antoni’s installation and thinking how vital the early '70s seemed. I spent a lot of time that year thinking about art and culture from the early '70s and how that decade was defined by the '50s with George Lucas’s "American Graffiti" and its saccharine knockoff "Happy Days," a regressive response to feminism and civil rights and anti-war protests. Meanwhile in the '90s, art reached for the conceptual work of the late '60s and early '70s and the literalism of feminism. Then, a couple years later disco came back feeding into rave culture. Yes, these are broad sweeps, but its return now? Maybe it’s middle age. Or maybe that’s just me there with my anguished grin. Maybe it’s easier for me to consider my own choices through a longer lens.

Perhaps some of this is nostalgia for a New York before it became a kind of themed shopping mall. You only have to look at John Miller’s photos of gay bathhouses (only one of which still stands) in the show to see the city is on the cusp of radical real estate change. Or, maybe it’s the Great Recession returning us to an earlier financial crisis. Or, Occupy and the punk DIY spirit of ad-hoc performance spaces like the Silent Barn? Melanie Fallon said also that 9/11 is now enough history that people can see more in the city’s past than just the fallen towers.

There’s a line of Marx’s I love from "The 18th Brumaire Of Louis Napoleon": “First time tragedy, second time farce.” It takes Karl into the realm of another Marx, Groucho and his brothers. Written about political dynasties, it seems to hold true for any sort of cyclical return. The day I saw “NYC 1993” I happened to meet friends for lunch at Orlin on St. Marks Place where I last ate in 1994. That night at dinner a woman at the next table had pale skin and a red-painted mouth. She wore a black lace baby doll dress à la Courtney Love. The artists I’d had lunch with talked about setting up a feminist reading group. It all felt like a time warp and as if the world did circle around and rotate fully on its access to return to that place. Only you can never go back. Remember that opening skit for the first episode of the first season of "Portlandia" (a show celebrating the mid-lives of people coming of age then), the “Dream of the '90s”? The decade was supposed to be “alive in Portland,” but seems to be everywhere.

David France’s inspiring ACT UP documentary "How to Survive a Plague" was 2012’s most lauded film and is being transformed into a miniseries on ABC. Meanwhile Republicans are signing on to the Supreme Court brief in support of gay marriage. It’s as if the culture wars are not only over but we won.

We are in a moment where the Xs and Ys that create identity are much less fixed. Teens can, thanks to Dan Savage and others, know it gets better, while gender is less defined and less binary. With Occupy, protest has not just a voice again but also humor and direction. Look at how the group’s offshoot Strike Debt is buying up medical debt. Feminism too is dominating popular culture with "Lean In." And, “NYC 1993” is good, very good, in fact. You should see it.

Still, none of the curators were in New York in that moment they’re celebrating (though the New Museum’s director was on the team responsible for the 1993 Biennial). One was a teen in Italy, seeing for the first time the Venice Biennale, an experience that was formative for him. Another was in high school and writes in the catalogue about the commodification of alternative culture, this before “alternative” was an iTunes’ genre.

The show offers a kind of mythic vision of New York that sounds romantic. Hell, it is. All those elements in my life could be reshuffled to look like fragments of an old New York, full of struggle and meaning — pregnant, stripper, Lower East Side … They read like a Larry Clark photo. Back then he was popular for his gritty shots of downtown life that became the basis for his movie "Kids." Or, those facts could just produce that same uncomfortable grin I share with Sussman. To me they’re awful. I remember feeling like I was drowning most of the time. My apartment was encrusted with cockroaches and phantoms of former tenants. Heroin dealers dominated my building; people would shoot up in the stairwell. My neighbor, the super’s wife, was raped, and I wonder still if this was retribution or to bully her husband into acquiescence.

I remember slipping out of my apartment the following summer and going to hang out with Chloë Sevigny on the set of "Kids," a block away. We were nominally friends. Movie stills are included in the show, as is a steel door ripped from Clark’s apartment emblazoned with stickers. The door was included that year in an exhibit at Luhring Augustine. But, romanticizing the life of a girl who discovers she has AIDS after having had sex once with a predatory teen hardly seems romantic at all.

A German artist Nadja Marcin in her early 30s has just made a conceptual version of "Kids," chopped down to 30 minutes and with adults in the roles of Jenny and Telly and the movie’s other teens. At first I didn’t get it. The dialogue was in German, and this seemed an homage. But, why?

Marcin grew up romanticizing the film, and now putting adults in the roles is stagey, like Brecht’s version of the movie, forcing this dissociative split between the two. She wrote about it to me eloquently, about being the same age as the kids of "Kids," 14, when she first saw it. “The guy who took me to the movie was 19 and thought he was Telly … I would soon wear the blue T-shirt with white stripes like Jenny. "Kids" started this wave in my German suburb. We all thought what was happening in New York was real, and being bored by the normality and stability of our surroundings, we started to simulate this ‘American lifestyle.’ This whole grunge feeling of no-way-out was very attractive.”

Marcin moved to New York for grad school at Columbia. Of course, the city was nothing like her teenaged expectations. Adults looked and dressed like "Kids," and whatever urgency there was to that original moment – if it had even existed – was long subsumed into, as she puts it, “Commodities of lazy weekend life in coffee shops and at mediocre concerts next to the standard nine-to-five job in Manhattan. Pink hair is okay, but all significance is missing, the underlying feeling, the urge, the necessity … It is all surface now … it is all fashion. It is emptied inside out.”

Her German version revisited the original locations, literally conflating the adult experiences with her old memories and commenting on both. She’s having a show at her New York gallery this spring featuring the film. I think she recognizes that awkward grin, the conflicted smile held too tight. I see it in her own awkward relationship to her youth. Tragedy and farce. The Janus faces of 1993, then and now.

Shares