Facebook has been used to find ex-lovers, childhood BFFs or the one who got away.

I used it to find the guy who, without my consent, made me his drug mule.

It was 1989, long before Israelis were involved in the international ecstasy trade. I was a University of California, Santa Cruz, student in need of a break. My plan was hardly original: Go to Israel, live on a kibbutz, learn some Hebrew.

Before leaving, I attended a Jerry Garcia Band show at the Greek Theatre in Berkeley. After the show, my friend and I got a ride back to Santa Cruz with some random guys, one of whom was Israeli. When I mentioned I was going to Israel in a few days, he asked if I would take a birthday present to mail to a friend. It was already late.

Given my strong Israeli-dar, I knew he would do no harm to Israel. What I failed to consider was whether he would cause any harm to me. He told me it was jewelry. He wrote his name and return address in Israel on the back of the envelope, and his friend’s on the front.

My mom was adamant that I not take it. Duh. But I was 20. I believed that my fellow Deadhead and Jew could be trusted; he was a brother.

“Did anyone give you anything to take to Israel?” I was asked at LAX. I offered it up. The questioner took it away, and disappeared behind the counter. He was gone at least 20 minutes.

“I told you you shouldn’t have taken it,” Mom said.

I shrugged her off.

The security guy returned and handed it to me.

“Is everything OK?” I asked.

He nodded. “Have a good trip.”

I shot my mom a look that said, “See? I knew he could be trusted.”

I landed in Tel Aviv 17 hours later. At passport control, I was told to go with three plainclothes police who took me to an interrogation room nearby. “If this is about that package, let me just give it you,” I said. “My relatives are waiting for me. I don’t want any trouble, and at this point, I don’t care if it gets delivered or not.”

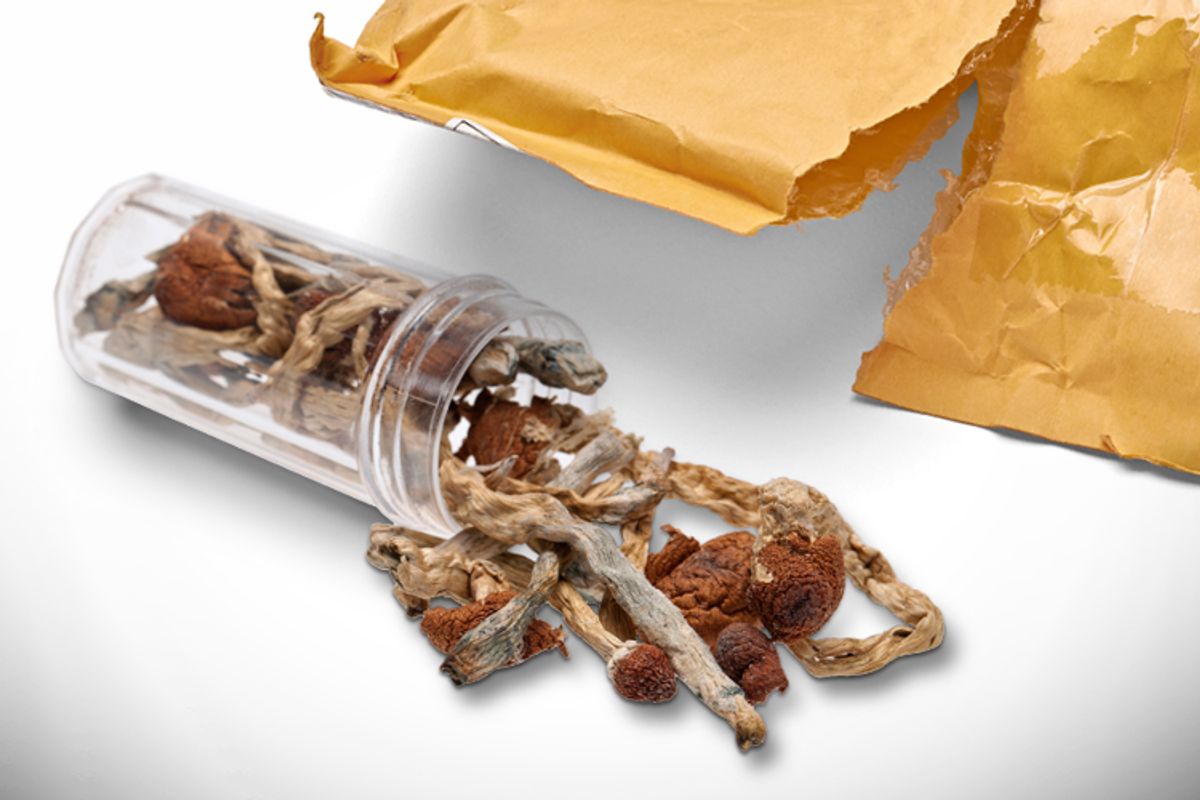

Ha. They sat around a table; I remained standing. One of them slid a pen along the envelope’s seal, holding it far from his body, as if it could explode. I truly thought I had nothing to worry about. That is, until I saw a plastic sandwich bag with no sandwich in it fall out.

“Oh my God, it’s drugs.” The words slipped out of my mouth as my body slid down the nearest wall. They stared. I felt like I was staring at me, too. Bat mitzvah Hebrew hadn’t prepared me to understand a word of what they were saying.

Psychedelic mushrooms had never appeared in Israel before. Israelis were tripping in Southeast Asia, but not bringing them home. Such idiocy was left to this American college student.

The police had no idea what they were, and it was up to me to explain to them what their effects were, how much this amount cost, and how large of a dose it was. I tried to strike the right balance between being just helpful enough, without seeming like an expert.

When I went to the bathroom, a policewoman came inside the toilet stall with me to make sure I didn’t flush anything down. It was the only time that I cried.

My luggage was meticulously searched at a nearby police station. A detective named Pini carefully translated and took notes of what happened into Hebrew. The juvenile part of my brain would have found his name hilarious had I been in another frame of mind.

“Alexandra, this is a very serious crime in Israel. You could go to jail for many years,” a man named Chaim threatened. Whenever I tell the story, I pronounce “Ah-leex-ahn-d-rah” rolling the “r,” just like he did.

“I came to stay on a kibbutz and learn Hebrew,” I stammered. “I’m not a drug dealer. Do you really think I would have told security about the package I was carrying if I were trying to sneak this in?”

They offered me a cigarette: a Noblesse, the strongest cigarette on the Israeli market. I’m not a smoker, but there must be a rulebook somewhere that says when being interrogated for bringing contraband into a foreign country, it’s impolite to refuse. I violently coughed. The detectives all burst out laughing: Their alleged drug-dealer couldn’t even inhale. I realized that everything was going to be OK.

They took me to a police station in downtown Tel Aviv. The package’s intended recipient lived right nearby. Pini took me to see if she would recognize me. I knew nothing would come of this, and she wasn’t home anyhow. Her mother did confirm through the intercom that the envelope-sender was a good friend of her daughter’s, and that he was now traveling abroad.

They searched my address book, looking for evidence of connections with any Israeli kingpins. They took my relatives’ phone number, in case they wanted to reach me in the next few days.

When I could finally sense it was almost over, and they admitted they pretty much knew I had been set up all along, I asked why they didn’t just take the package from me in L.A.

“We knew it was an Israeli matter,” they said. “It would have gotten lost in L.A. and we want to catch those responsible.”

And then, just like that: “You can go.”

I stared at them. “You’ve had me for five hours,” I pleaded. “I couldn’t change money. I don’t know where I am. The least you can do is take me to my relatives who live in Tel Aviv and explain.”

Pini did. They were so relieved, and hadn’t yet called my parents. They fed me shakshuka, which remains high on my list of comfort foods. The incident – they did not consider it an arrest and told me I would have no criminal file -- made an Israeli paper, without my name.

Though traumatic then, it became part of my personal narrative, “The Crazy Time When.” We all have such tales.

And that was it, for 23 years. Until recently.

Friends were over for Shabbat dinner. It came up. My husband has heard the story many times by now. I tell it sometimes with a lot of drama, when I am in the right mood, when I know I will have an appreciative audience.

“Do you remember his name? Have you looked for him on Facebook?” a friend asked. “To tell him how messed up that was?”

Of course I remembered his name. He had written it on the envelope, and I heard the detectives say it repeatedly. When a friend of mine married an Israeli some years ago with the same first name, I immediately asked him his last name, knowing instinctively that it wasn’t him, but needing to be absolutely sure.

Finding him was that simple. I recognized him from his photo, and we even had a friend in common. I don’t know her very well, but I called her, and told her the story. Incredulously, she asked exactly when the incident took place, and told me that he might have been staying with her in Santa Cruz at the time he gave me the package.

“He’s a nice guy,” she told me. “He has a few kids now. I’m shocked that he would do that to you. I’m not trying to justify what he did, but we all do stupid things when we’re young.”

Do we ever.

I sent a scanned image of the article with my message, saying that I had no hard feelings about it now, but wanted to know what ever happened to him. I asked if he would be open to a Skype call. He sounded surprised to hear from me, but also grateful.

Afterward, I told a friend I had reached out to him, and she asked me what I hoped to get out of it.

“I’m not sure,” I said. “It’s not like I need an apology from him to move on with my life.” At the same time, I know from past experience that hearing “I’m sorry,” even so many years after the wrong was committed, can heal a psychological wound in unexpected ways. What I didn’t expect was that he needed to hear from me more than I needed to hear from him.

We Skyped a few days later. And as it turns out, he knew all too well how messed up that whole thing was.

The woman whose name was on the envelope had gotten the worst of it, since she admitted to the police that she asked him to send the drugs out of curiosity. He only had to spend one night in jail. But he was so racked with guilt for what he’d done to me that he brought it to therapy. Finally, his therapist advised him to move on, since he didn’t even know my name. He hadn’t touched drugs since, because drugs turned him into a kind of person he didn’t want to be.

I told him that, in general, I was a trusting person until people gave me reason not to trust them. He said, “I hope you are still like that, that I didn’t have a hand in changing that about you.”

I had to think about it for a minute, but knew that for the most part, he hadn’t.

I told him how hard my mom tried to dissuade me from taking it, and in response, heard what, of course, I’ve known since this whole thing happened, “Your mother was right.”

It was because she was always right that I asserted myself so strongly on this one; but, of course, nothing could have taught me a better lesson. She left this planet almost 11 years ago never knowing this happened, in large part because, in this particular instance, I couldn’t bear to hear the “I told you so.”

“I remembered that you were really nice and didn’t deserve that,” he finally said.

He told me that he comes to the Bay Area every couple of years, and would like to meet me the next time he does. We’re going to meet in August.

He apologized, several times, and thanked me profusely for contacting him. It was such a gift, he said. He felt he had been carrying the residue from this for all of these years and now, he felt free.

Shares