In 1889, Joseph Pulitzer’s New York Evening World held a contest to determine America’s “Champion Dreamer.” The winner was a Maryland junior college instructor named Buckey who dreamed he’d shot a man who wore a thick black mustache. As Buckey walked to work the next morning, the vividly seen face of his victim was suddenly before his eyes a second time. The two men jumped back, equally startled. “For God’s sake, don’t shoot me!” cried the stranger. Buckey and he recognized each other, because they had dreamed the same dream.

In the midst of the Civil War, newspapers North and South featured stories about soldiers whose dreams predicted war’s end. On April 25, 1863, Boston’s Saturday Evening Gazette demonstrated the credence it had given to a local artilleryman’s dream by printing a retraction, regretting that the man’s six-week-old vision of April 23 as “the date of Peace” had not been met. The wife of a Union general, meanwhile, could not banish from her fragmented sleep narratives gruesome premonitions about her sons: “One night I dream that Paul is drowned, another that Benny is dead.”

What did dreams mean for Americans who lived in the century before Sigmund Freud undressed their repressed desires and ushered in the “Self-Help Century”? A pretty basic question, yet somehow no historian had really delved into it before. We know much about the physical contours of our forebears’ world, far less about the emotional contours. As I began to dig up old dreams for my new book, "Lincoln Dreamt He Died," the more I paged through preserved diaries and letters, the more committed I became to answering the question cultural historians can’t help but ask: Were they like us? It would be a history of America from the inside out, the “American Dream” in a most literal way.

Despite its title, "Lincoln Dreamt He Died" does not present as many famous people as ordinary diarists and letter writers, because I wanted to capture as broad a cross-section of the population as possible, tracking such elements as the colors sleepers were seeing, the sounds they were hearing, the frequency of dreams containing dialogue, or the percentage of anxious vs. pleasant dreams (it’s the same for theirs as it is with modern dreams: about three-fourths are anxious). I can report, at least, that the famous people whose dreams I track are surprisingly forthcoming, considering that we imagine early Americans to have been a less self-revealing people than us moderns.

Were they like us? Not exactly. Lots of 18th-century people heard voices while unconscious and responded to the musical soundtrack of their sleep narratives – a phenomenon less common in modern dream reports. To take one example, Joseph Priestley, the discoverer of oxygen, speculated that “no impression ever made on the mind is ever wholly lost,” as he related a dream in which he was attending a lecture. The speaker’s “peculiar” tones resembled musical notes – loud sounds that remained in Priestley’s head for a short time after he woke, though the image of the speaker and audience had by then dissipated.

“I see dead people” dreams were extremely common. Benjamin Rush, born in 1745, was a physician, University of Pennsylvania professor, and signer of the Declaration of Independence. He had faith in his medical colleagues’ standard prognosis: that dreams indicated physiological impairment. Ordinarily that meant indigestion, but in extreme cases a hysteria that could lead to madness. At the same time, Dr. Rush considered his own dreams delightful and instructive. In one of his death-defying dreams, the good doctor was inside the gates of a graveyard, watching the comings and goings of ghosts, some of whom he had known in life. The risen dead dressed in their burial shrouds did not spook him, but the “noise in the air which I supposed to be the last trumpet” was hard to forget. His dream was filled with sound: “I heard a woman vociferating to a man I supposed to be her husband.” She demanded, and her mate “meekly” complied. Nearby, a different marital scene unfolded: “It was a man kicking his wife and dragging her by the hair … and then leaving her by saying, ‘There, take that, you bitch.’” Who knew America’s founders were so caught up in gender politics when they weren’t philosophizing about government?

The next generation evidenced similar concerns, ratcheting up the bizarre. Popular essayist, lecturer and Transcendentalist poet Ralph Waldo Emerson fretted all his life about the dissolving properties of memory, and he repeatedly tried to nail down the most absorbing of his dreams. One he had in the late 1830s that he called “droll” was particularly vivid. He found himself attending a conference on marriage, when one of the speakers suddenly “turned on the audience the spout of an engine which was copiously supplied from within the wall with water.” This man shook the hose in all directions and “drove all the company out of the house.” The dreaming Emerson relished the scene: “I stood watching astonished & amused at the malice & vigor of the orator, I saw the spout lengthened by a supply of hose behind, & the man suddenly brought it round a corner & drenched me as I gazed. I woke up relieved to find myself quite dry.” His recorded postscript illuminates Emerson’s lighter side: “the Institution of marriage was safe for tonight.” He says nothing, however, about any sexual allusion in the man shaking his engorged hose – Freud had not been born yet.

Louisa May Alcott, the author of "Little Women," grew up adoring Emerson, which half-explains her own facility for conveying the stuff of dreams. While visiting Lake Geneva in 1870, she sent home to her sister what she, too, termed “a droll dream,” which involved their ne’er-do-well educator-father. In the dream, she is back in their old neighborhood but it looks different – her house is gone, replaced by a castle – and she asks a neighbor, while he is wallpapering a room, to direct her. This is how she learns that she died 10 years earlier and left her father a plot of land on which he built his long-wished-for school. She sees her reflection, and discovers herself to be “a fat old lady, with gray hair and specs.” When she finds her father, he, on the other hand, is years younger, “with brown hair and a big white neck-cloth, as in the old times.” She laughs at the absurdity of it all.

Until the middle of the 19th century, many more Americans saw dire warnings than odd humor in dreams. In a good number of them, angels took the dreamer on a tour of the afterlife. People away from home wrote urgently to find out whether the coffin they saw during sleep indicated that someone in the family had died. In the American Revolution as well as the Civil War, separated sweethearts wrote ecstatically, conveying literal dreams of happy reunions; but some men in army camps dreamed of being coldly met by their wives on their return home. Abandonment dreams were common. Prisoners of war, not surprisingly, dreamed of sumptuous meals, and woke to dirt and despair.

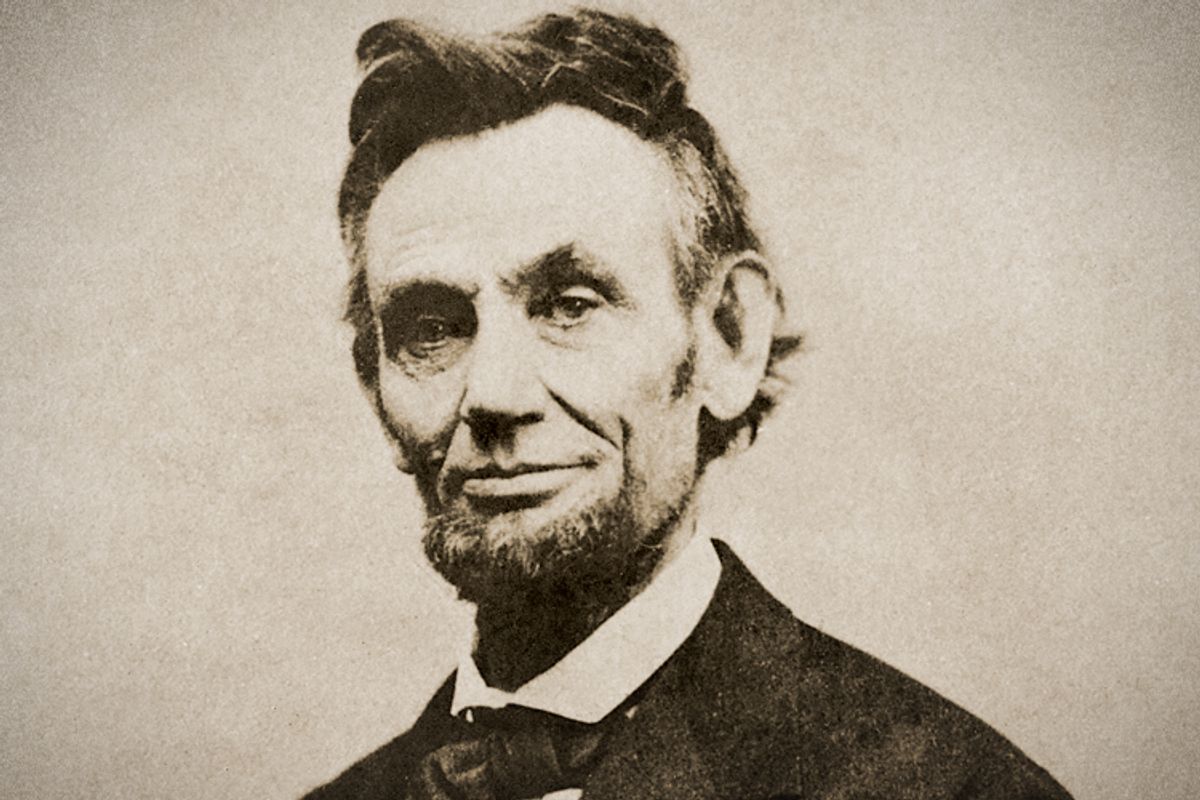

As for the book’s title, Abraham Lincoln was one of countless Americans coming of age in what we term the Romantic era, who believed that dreams could prophesy. Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” – note that his company is called DreamWorks – opens with a dream sequence. There is basis in fact for this directorial decision.

Lincoln memorized the haunting poetry of Lord Byron, reveling in the “wide realm of wild reality” that comprised the Romantics’ dream world. After reelection, he confided to his close friend and bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon that he dreamed of seeing his own body lying in state. “Who is dead in the White House?” the dreaming Lincoln asked a soldier standing guard. “The President,” he was told. “He was killed by an assassin.” Though Lamon was generally reliable, we cannot be absolutely certain that he didn’t dress up his memoir here.

Mark Twain was another who swore by the supernatural character of certain sleep narratives. He dreamed of his younger brother’s death in a riverboat explosion, not long before it took place. “Dreamed of a whaling cruise in a drop of water,” began another of his many documented dreams. Whereas Thomas Jefferson simply referred to dreams as “our nightly incoherencies,” Twain called them “psychic phenomena.”

Times were changing for dreamers. It is more than a little curious that the mass of ordinary, as well as extraordinary, Americans came to reject standard medical thinking, going along instead with the language of opiated poets and gothic novelists that so fascinated them. Celebration of the individual, and the buoyant confidence that grew alongside the very idea of the “American Dream,” was reflected in a literature stimulated by the sleep narratives of the nation’s most prized authors; their dream-infused productions in turn affected the sleep narratives of everyday readers. Washington Irving’s “Rip Van Winkle” commanded their attention, and so did Mary Shelley’s "Frankenstein."

In the late 1850s, Caroline Clay Dillard, a young North Carolina woman, peppered her diary with Irving’s pathos-driven graveside laments, Byron’s dream-laden poetry – and a smattering of her own dreams. In one she saw her deceased toddler nephew and “heard strains of music and looking ahead saw a bright dazzling glorious City.” Dream life and real life were easily interchangeable in an age when frequent early death darkened the sunlit days of every family. Desperately in love with her former teacher, who subtly hinted at his feelings for her, Miss Dillard wrote to herself: “O! I’m dreaming.”

Her preoccupation was the norm. The 19th century’s classic literature of sleep-borne journeys, time travel and mystifying reanimations only intensified with the years. Twain’s "A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court" and H. G. Wells’ "The Time Machine" are but two examples. Americans’ engagement with dreams was such that when Freud crossed the Atlantic, great numbers were immediately intrigued and before long ready to submit to psychoanalysis.

We know what we mean when we use the term “American Dream”: It speaks to collective hope, national pride and the personal security we see as a possibility for those who believe in its magic. Studying literal dreams is another form of magical belief, another delineator of culture, another marker of hopes and fears. The 1889 New York Evening World’s “champion dream” came with a certificate of authenticity. (Who doesn’t wonder how something that melts away in seconds can be authenticated?)

Yet I think the dreams I have collected indicate more than signs of individual strength or weakness: They are historical treasures. Since classical times, dreams have suggested to the multiplying millions who preceded us that physical death does not necessarily mark the end of sentience. Even those not known in their communities as conventionally religious found themselves drawn in. Judith Sargent Murray, a Revolutionary era feminist writer in Boston and a child of the rational Enlightenment, told Dr. Rush that she dreamed of her husband’s dying in the Caribbean on the very night she later learned he had perished. Death stalked the early American dreamer.

I have found in my research that while Americans claimed, even then, to be a practical-minded people, they were actually mired in superstition, haunted by their dreams, and no less delighted by the invention of the Ouija board than by the cotton gin. It is their unsupported claims to wisdom that adheres most to our ancestors, and renders them intensely interesting as historical subjects. After the American Revolution, dreamers did not immediately regard dream life as a form of autobiography. It took decades before they knew their dreams as we know our dreams – as a facet of longing for which the imagination serves as a delivery vehicle.

Today’s dream scientists speculate that the function of dreams may be to restore body and mind, helping the brain to manage threats and disturbances. They say that our remembering dreams may in fact be nothing more than an evolutionary fluke. For the cultural historian, however, studying the extant dreams of past societies holds out the promise of unearthing new clues to the collective identity of entire generations.

I feel comfortable in concluding that you cannot fully appreciate the 20th century’s fascination with psychoanalysis until you first appreciate the 19th century’s fascination with dreams. The road that brought them to Freud is paved with colorful imagery and soundscapes, hauntings, illusions and echoes of love. Their footprints may be gone from our world, but in these most personal of texts they still speak to us.

Shares