Smokey the Bear thought he smelled a fire in the woods. But as he approached the clearing and saw a giant derrick jutting out into the sky, he realized that what his nose had picked up was the scent of hydrocarbons. It was another piece of evidence that the increasingly widespread method of oil and gas extraction known as fracking was poisoning the environment that he and his human friends depend on. He decided something must be done.

Smokey the Bear thought he smelled a fire in the woods. But as he approached the clearing and saw a giant derrick jutting out into the sky, he realized that what his nose had picked up was the scent of hydrocarbons. It was another piece of evidence that the increasingly widespread method of oil and gas extraction known as fracking was poisoning the environment that he and his human friends depend on. He decided something must be done.

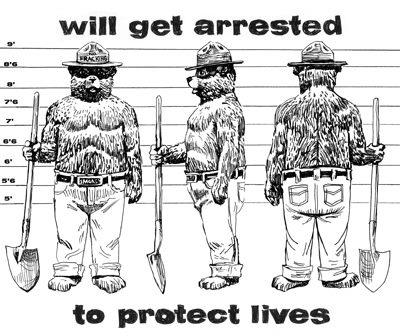

At least that’s the way that artist, Occupy Wall Street veteran and environmental activist Lopi LaRoe sees it. But last week she received a letter threatening her with jail time and thousands of dollars in fines for enlisting Smokey to the anti-fracking cause.

In the fall, LaRoe created an image of Smokey that altered his famous invective “Only you can prevent forest fires” to “Only you can prevent faucet fires” — a reference to the phenomenon of flaming taps that occasionally occur near where fracking takes place. The adjustment seemed to her in line with the message of conservation Smokey has come to embody.

“This is the radicalization of Smokey the Bear,” said LaRoe. “This is Smokey waking up and saying, ‘Oh you didn’t do that to my environment.’ Smokey wants to fight the corporations and protect the air and the water and the plants and the animals and the people.”

Her parody went viral. She began printing T-shirts at the insistence of friends on Facebook, but demand quickly surpassed those in her immediate circle of contacts. Soon she was packing Smokey in FedEx envelopes and sending him off to Australia and other far-flung terrains. There are also tote bags and patches with the Smokey meme available at LaRoe’s website. (The tote bags, she advertises, are “great for dumpster diving.”) LaRoe says she’s not out to become rich and the money she charges customers goes toward covering her costs so that she can keep spreading the message of faucet-fire prevention far and wide.

“It spread like wildfire,” she said, grinning ear to ear.

Not everyone is amused. LaRoe received a cease-and-desist letter from the Metis Group, which serves as legal counsel for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service division. The letter informs LaRoe that Smokey, his character and his slogan are property of the U.S. government and warns that she has until May 2 to halt the use of Smokey on her “products” and to stop distributing electronic copies of the meme. Otherwise, she faces up to six months in prison and a penalty as high as $150,000.

“Any time anybody uses Smokey’s image for anything other than wildfire prevention,” said Helene Cleveland, fire prevention program manager for the Forest Service, “it confuses the public. What we’re trying to do is keep Smokey on message.” Cleveland added that the 1952 Smokey the Bear Act takes the character out of the public domain and “any change in that would have to go through Congress.”

Two other entities besides the Forest Service claim joint rights to Smokey. The National Association of State Foresters — a non-profit organization consisting of directors of U.S. forestry agencies — and the Ad Council.

Remember “This is your brain on drugs”? Or the Indian weeping over pollution? They were the Ad Council’s handiwork. A non-profit, it describes itself as a promoter of “public service campaigns on behalf of non-profit organizations and government agencies” with a focus on “improving the quality of life for children, preventive health, education, community well being and strengthening families.” Smokey the Bear was born at the Ad Council, on the desk of abstract expressionist and Marx-influenced art critic Harold Rosenberg, who had a part time job there in the mid-1940s.

The Ad Council’s board of directors is a conflagration of representatives of the world’s wealthiest corporations, including representatives of such companies as General Electric, which announced plans last month to spend $110 million on a research lab devoted to the study of fracking, and finance giants such as Citigroup and JPMorgan Chase. On its website, Citibank advertises an “extensive array of deposit, cash management and credit products” for oil and gas drillers, while a JPMorgan Chase subsidiary boasts its “Oil & Gas Investment Banking group covers the complete oil and gas value chain, which includes exploration and production, natural gas processing and transmission, refining and marketing, and oilfield services.”

LaRoe believes that those who claim to own Smokey “don’t care that I’m selling a few T-shirts. They’re out to crush the meme.”

Both the Ad Council and the Metis Group declined to comment for this story.

Despite the warnings in the cease-and-desist letter she received, the May 2 deadline to shut down her site and retire her anti-fracking Smokey came and went; LaRoe has not ceased or desisted. Instead, she enlisted the help of her own legal counsel, who fired back with a letter to the Metis Group on Friday. In it, attorney Evan Sarzin argues that LaRoe ‘s culture-jam appropriation of Smokey is permissible under the fair-use exemption to exclusive copyright ownership and chides the the Forest Service for attempting to infringe on LaRoe’s First Amendment rights.

Sarzin also points out that this is not the first time the Forest Service has sought to silence environmentalists for appropriating Smokey’s image. In the early 1990s, the Forest Service demanded reparations from the Sante Fe-based conservation group LightHawk after it used Smokey’s likeness in ads critical of the agency’s practice of auctioning off land to timber companies. (The Forest Service, as part of the Department of Agriculture, makes its land available for commercial use.) Unlike LaRoe’s Smokey, LightHawk’s black bear appeared angry and wielded a chainsaw. “Say it ain’t so, Smokey,” read the ads.

With legal funds provided by the Sierra Club, LightHawk sued the Forest Service in 1992 for infringing on its freedom of speech. The court eventually sided with the plaintiffs, noting that “the satirical use of Smokey the Bear to criticize Forest Service management techniques is unlikely to cause confusion or to dilute the value of Smokey the Bear to help prevent forest fires. Thus the Forest Service cannot have a compelling interest in prohibiting such use.”

Sarzin also calls attention to the fact the Forest Service’s own research points to environmental degradation caused by fracking. A 2011 study published in the Journal of Environmental Quality by Forest Service researchers linked frack fluid to the death of 150 trees in West Virginia’s Monongahela National Forest. Despite their findings, the Forest Service is considering approving fracking leases in the nearby George Washington National Park. The Southern Environmental Law Center, which opposes the plan, says it represents a threat to local wildlife — including the black bear.

A report released last month by the the National Parks Conservation Association warns that fracking for oil is decimating the ecosystem surrounding Theodore Roosevelt National Park, named after the Republican president who founded the Forest Service. “Unless we take quick action,” the report warns “air, water and wildlife will experience permanent harm in other national parks as well.” Thus, Sarzin writes, LaRoe’s Smokey meme “is a message that the Forest Service should endorse.”

LaRoe hopes that by gaining publicity she can force the Forest Service to take a stand against fracking. In order to continue the fight, however, she says she needs the support of groups whose mission it is to defend civil liberties or protect the environment to provide legal defense funds — just as the Sierra Club did for LightHawk.

“This about more than me as an artist,” LaRoe said. “This is about everybody’s right to freedom of speech and a healthy environment.”

Her childhood memories of Smokey, she explains, are compelling her to keep raising faucet-fire prevention awareness despite the threat of jail time. “When we were little kids we were taught that there is this bear out there that wants to protect our forests. Smokey is our bear. He belongs to the people.”

Shares