Afoot and light-hearted, I take to the open road,

Healthy, free, the world before me,

The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.

— Walt Whitman, Song of the Open Road

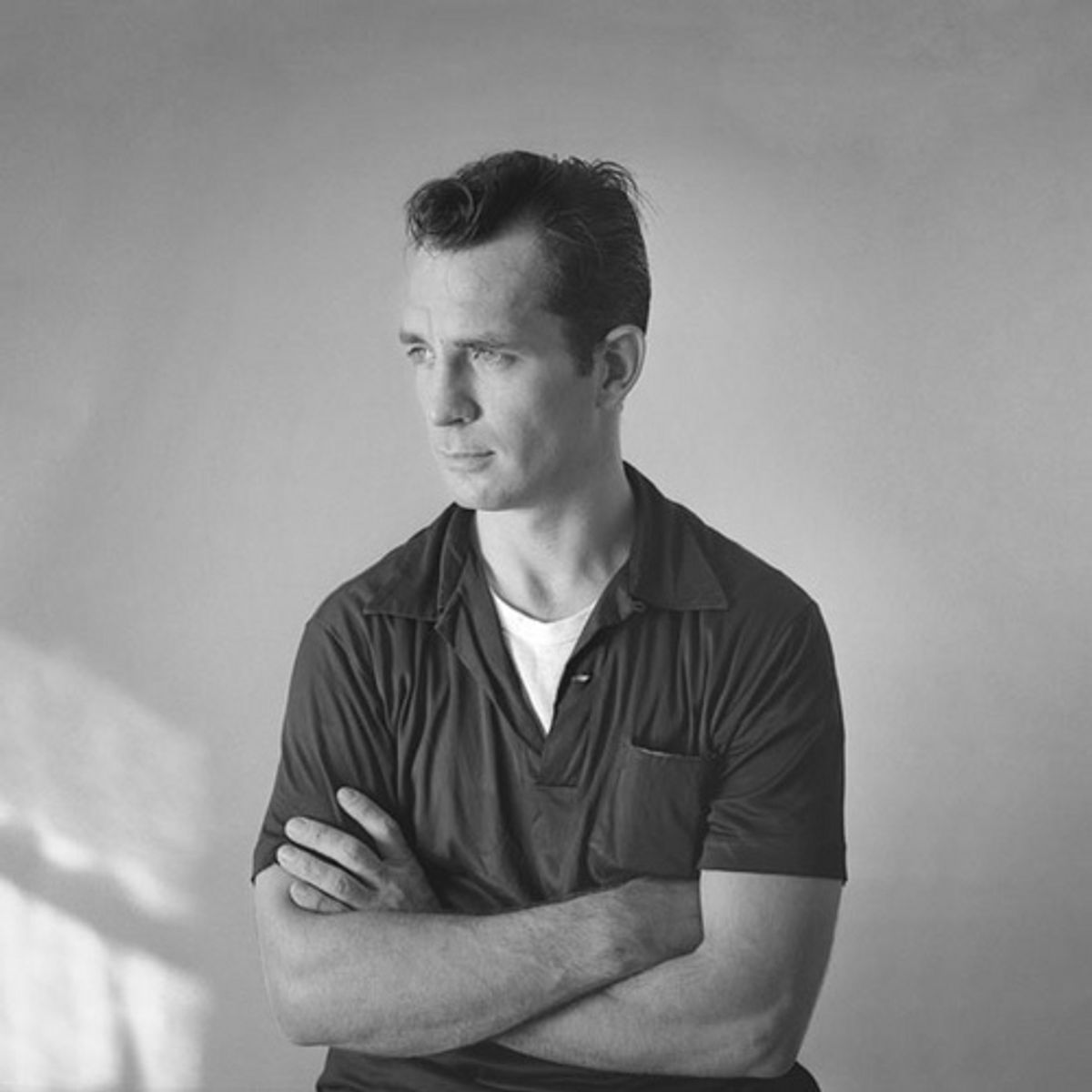

The FRANCO-AMERICAN WRITER JACK KEROUAC (1922–1969) is one of the most identifiable and branded of his generation. There are already more than half a dozen extensive biographical treatments, and many of his letters have now been published, including Road Novels, 1957–1960, his Complete Poems in the Library of America series (2007, 2012) and The Portable Jack Kerouac (1995). Why do we need a substantial new look at the author now, that largely ends late in 1951 with the completion of his best-known book, On the Road, which did not actually appear until 1957 when his oeuvre was blossoming but his melancholy decline began?

Why indeed. First, because all but one previous biography are highly unsatisfactory, misleading about meanings and events and not adequately based upon the abundant Kerouac archive, once closed for 30 years, and deposited in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library in 2002. Second, because The Voice Is All is written by a literarily astute woman who was his helpmate/lover more than half a century ago and knew many of the dramatis personae who belonged to Jack’s overlapping circles that figured so vitally in his evolution as a person and writer. Third, because Jack’s On the Road has recently been made into a new film. (In 1957 Marlon Brando ignored Jack’s letter requesting him to play the lead as Dean Moriarty. C’est dommage.)

And why am I engaged in writing this? I invited him to read at Harvard and hosted his happy/sad, sometimes wild, and characteristically zany visit to Lowell House, a neo-Georgian Harvard undergraduate residence in March 1964. So I knew him briefly after the acme of his success, which Joyce Johnson may yet choose to write about. I almost hope not, because it was a tough time and in this book she has handily revealed his years of discovery, growth, and troubled complexity in a manner that should satisfy the most zealous fan of the “Beat Generation” — which was Jack’s phrase, appropriated and made widely known by John Clellon Holmes, a writer and devoted pal, one of many, but along with Allen Ginsberg, the best and most constructive. Jack had a genius for friendship with men and women, gay and straight, though his bonds with men tended to be considerably more enduring. Women flitted in and out of his focus like the pretty color scraps falling about at the far end of a kaleidoscope — and he from their beds. His restless life was packed to its perimeters with literature and, eventually, as Johnson makes very clear in her fine concluding section called “Interior Music,” writing what Allen Ginsberg labeled “spontaneous bop prosody.” Talk about le mot juste. That nails it.

Kerouac’s most important influences were Dostoevsky (Notes from Underground was a seminal text for him), Thomas Wolfe, Whitman, Melville, and eventually Céline, Proust, and James Joyce. Is that startling? Perhaps not so much, but mix in Emerson, Thoreau, and Francis Parkman’s Oregon Trail (makes sense, another man from Massachusetts “on the road” a century earlier), Twain and Emily Dickinson (how discrete they seem from one another — yet it is thought that he satirized her as Emmeline Grangerford inHuckleberry Finn), and then Hemingway and Fitzgerald (he called them the “leaver-outers” because of their verbal economy, their predecessors being the “leaver-inners” — quips that actually originated with Wolfe himself). Kerouac once remarked that “my subject as a writer is of course America,” but the roster above would be very incomplete without noting his assimilation of Goethe especially, Shakespeare (think Hamlet), Tolstoy, Rabelais, Stendahl, Rimbaud, Gide, H.G. Wells, Spengler, Thomas Mann, and the New Testament. He inhaled them all.

Wolfe and Dostoevsky ranked uppermost, but Jack ultimately tipped much more toward the latter — despite his desire to be a great American writer — because of the growing darkness during his last decade, even as he remained ebullient at times. He tried Tolstoy’s moral essays but felt far more affinity with Dostoevsky’s “Karamazov Christ of lust and glees.” Savor that. It’s exactly right.

References to angels, saints, Holy Ghosts, archangels, and fallen angels are sprinkled through Jack’s journals, letters, and texts. Despite becoming a nonbeliever early on, vestigial traces of Catholicism lingered even as he sought sanctuary in liquor, drugs, and oblivion. The death of his idealized older brother, Gerard, when Jack was four, left him with a permanent fixation on death, loss, and family. His mission, as he saw it by the time he wrote On the Road, was to “moan for man.” This was no pretense. He did just that.

There is much to lament in the saga of his life, and quite a bit is surprising. In his Book of Dreams Jack echoed what he had written while at sea as a merchantman: “Rough seamen who saw my child’s soul in a grown-up body broke my spirit by spitting and cursing.” Jack was not a gentle soul, but I never saw him spit or curse. Yet he certainly rejected refinement. Felt tacky to him. When Robert Giroux, editor of his first book, The Town and the City (1951), invited Jack to rent a tux and accompany him to the Metropolitan Opera to see the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, dance became an exotic experience, not to mention dinner afterwards at the Blue Angel in the company of Burgess Meredith, the young Broadway lyricist John Latouche, and Gore Vidal with his socialite mother. Such occasions with Giroux made this Dharma bum exceedingly uncomfortable and he associated them with what he called “white ambitions” and rose bushes, his imagined emblems of upward mobility and artificial symbols of success.

He preferred the company of aspirational unknowns like himself and Neal Cassady inOn the Road, yearning all the while for imaginative literary achievement of a new order. He liked low-lifes better than the high life and spent many more days down-and-out than on a roll. When money came it disappeared swiftly. His affair with the classy Sarah Yokely ended badly and he included only one line about it in On the Road, referring to “a woman who fed me lobsters, mushrooms-on-toast, and Spring asparagus in the middle of the night […] but gave me a bad time otherwise.” She was too rich for his blood.

At the core of Johnson’s compelling book (pace some dismissive recent reviewers) there is a motif more important than alcohol, sex, and drugs, the familiar litany that is all too true and tragic. One prevailing theme is that Jack never became or felt entirely American — not just as a youth in Lowell, Massachusetts, but growing up in its French-Canadian enclave called Centralville, where he became a football star and earned scholarships to Boston College and Columbia, choosing the latter. In his teens, however, Jack frequented the Lowell Public Library, twice a day when possible, and read voraciously. The halfback was also a bookworm, and the latter prevailed as his perplexing Columbia experience proved.

His birth language was French, and initially he spoke the Canuck dialect called joual. Mastering English became an almost lifelong process that never entirely satisfied him. As a youth he spoke English slowly. In 1951 he actually tried composing in joual even though it lacked the thesaurus-full subtleties and richness of English. He liked its roughness, its vernacular qualities. He would then translate from joual to capture that vernacular flavor in English.

Near the end of her book, with On the Road completed, Johnson observes with clarity and grace what happened next to Jack’s experimental prose:

Without proclaiming his “raw” Franco-American identity, Jack was finally inhabiting it in his sketches, as he would do more and more in the books he wrote next, addressing the feelings of shame and exclusion it gave him … and even starting to bring words from his own language into the text — the dreams his narrator has are called rêves, for example, in the first section of Visions of Cody. In a later section of the book, he would finally dare to write entire passages in joual, set alongside their translations.

Johnson would join canonical affirmations of Jewish-American, African-American, Chinese-American, and other ethnic literatures with Franco-American writing, and with Kerouac as its avatar. Such an accommodation is anticipated by Louis Hémon, also Breton, who came to Quebec in 1912 and followed a vagabond-like existence that prefigured Jack’s four decades later.

Another durable theme in The Voice Is All, not new but nicely sustained for different phases of his life, involves Kerouac’s dual nature or “divided soul.” In 1943 he wrote to a beloved high school friend, equally cerebral, then serving in the Pacific. The feelings he expressed kept fluctuating between “unguarded expressions of emotion and self-protective coldness, as if two different Jacks were writing to him.” Later he wrote plaintively to yet another Lowell friend, part of his athletic and partying group, that he had spent his entire youth trying to bring together in one single knot “two ends of a rope.” “Sebastian was at one end, you on the other, and beyond both of you lay the divergent worlds of my dual mind.” The temperaments of these two friends represented a yearning for art and culture versus the “macho know-nothings” of Lowell. He understood himself all too well at age 21. Near the very end of Kerouac’s falling-in-love-again life, he married Sebastian’s sister (four years older than Jack), thereby making a Greco-French alliance that brought a very long family friendship full circle.

The dual aspects of his nature surfaced throughout his life, “poet and hoodlum,” and sometimes “whoremaster”; but it was the poetry side that he so often yearned and worked for in his 20s and 30s, going jobless and penniless in order to create time to write. Friends laughed when at 14 and 17 he said that he wanted to be a writer. InOrpheus Emerged Kerouac dealt with what Johnson calls his “internal dividedness” by splitting his protagonist into a young symbolist poet called Michael (“the genius of imagination and art”) and Paul, a penniless provincial vagabond (“the genius of life and love”) who has come from “the road” to follow Michael to an urban university. “The reader soon realizes that Paul and Michael are two halves of the same person.”

Kerouac is not readily remembered as an intellectual, and Johnson never quite calls him that; but it needs to be noted that by the age of 10 young Ti-Jean, his joual name, was reading voraciously. He skipped the sixth grade, and in the service at Newport, Rhode Island, he recorded the highest IQ at the base. He discovered Proust at the age of 22 and later carried Remembrance around with him in a battered, beer-stained briefcase.

Allen Ginsberg, who regarded Jack as his big brother, introduced him to Nietzsche and Aldous Huxley. His reading, always eclectic, turned increasingly American beginning in 1946.

Johnson describes an extraordinary evening in Ginsberg’s room at Columbia in September 1945. Allen sided with William Burroughs, both gay, during an intense debate between them, the non-Wolfeans, and the Thomas Wolfe devotees (Kerouac and a close friend named Hal Chase from Denver who eventually put him in touch with Neal Cassady, prototype for Dean Moriarty).

The battle took place in a room shared by Allen and Hal. Jack and Bill sprawled on one bed, Hal and Allen on the other, all four high on Benzedrine. Quite a scene.

According to Hal, the two heterosexual Wolfeans, he and Jack — Hal was fed up with Allen and Bill trying to convince him that he must be gay — upheld their idealistic love of America (even though at war’s end Jack still considered himself only half-American), whereas the Baudelairean non-Wolfeans (Jack called them the “Black Priests”) looked to European letters for inspiration and tried to corrupt the two macho Americans. Despite his avid absorption of European “greats,” Jack grew to identify European culture as decadent.

With time, however, Ginsberg became upset at the prospect of such splits among this tightly bonded group and their affiliated sisterhood. As a semi-communal clan they gradually became the Libertine Circle living at the notorious apartment 51 on 115 W. 115th Street in Morningside Heights. Drugs, free love, and a communion of souls coupled in various melds through many a long night. That’s when and how their self-perception of “beat-ness” emerged.

Despite a considerable amount of louche behavior, Jack could work on three novels at once in a kind of furor scribendi. At times he described himself as a “writing machine,” and as he eventually demonstrated with the famous penultimate draft of On the Road, Jack could pound away on his clunky manual typewriter for endless hours, days and nights, living on coffee, cigarettes, and adrenaline. As he finished writing The Town and the City in September 1948, he emerged from three years of relative seclusion and labor with “a kind of manic love for everybody.” Also, with an augmented hunger for cultural knowledge. At the New School for Social Research he enrolled in courses on mythology, the Russian novel, and Beethoven as well as a writing workshop. A friend noticed him listening with special intensity to lectures on “The Twentieth-Century Novel.”

Mid-way through Voice Is All, the model for Dean Moriarty, Neal Cassady — an autodidact, car-thief, and Proustian jailbird — arrives in New York from Denver and engages with Jack near Columbia in December 1948. Jack had gone to Denver the year before, but as early as 1946 he began thinking about writing a “road novel.” Initially he envisioned a solitary journey, but with Neal at hand providing the perfect soul-mate for drinking, sex, book talk and pranks, the stage was set for several years of “experiences,” ready-made food, and fuel for writing. Neal was not present non-stop: he had two women to support back home, and Jack remained close with Allen, John Holmes, and others, but he invested his literary self in Neal, and On the Road resulted.

During the winter of 1948–49 Jack began calling his work-in-progress “On the Road.” Like another, parallel project, it was concerned with duality and had two protagonists, one again the alter ego of the other. As Johnson helpfully remarks, Jack’s admiration for Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night, as well as a recent rereading of Huckleberry Finn“undoubtedly gave him new confidence in this idea — although neither Céline nor Twain inspired him at this point to allow himself to use a first-person narrator.” During that same seminal winter the word “beat” began to appear in Jack’s journals.

On January 16, 1949, Jack and Neal set forth from New York City. A few nights earlier Jack rejoiced that he was keeping a diary so that he could record himself saying to Allen and Neal at the West End bar: “This life is our last chance to be honest,” after which Allen asked, “How did we get here, angels?” The purpose of the trip for Jack was fresh experience, plain and simple. Like the Abstract Expressionists with paint, Jack wanted to write about action — his own and others’. Like Jack, but even more so, Neal needed constant motion. A spontaneous, energetic, sex-crazed con artist, he was regarded by Jack’s other buddies as a psychopath. Neal was so cool and hip that he made even Jack feel “inauthentic.” Whereas Neal chased women insatiably (he also made love with Allen), women pursued Jack. Despite some mutual jealousy, the duo did like to share women. Jack broke many hearts, including Joyce Johnson’s in 1958, as she reflects in her intimate and candid collection of their letters, Door Wide Open, which is a very worthwhile book (hereafter DWO). There are now half a dozen books written by Jack’s former lovers. Johnson’s are the best and Voice Is All corrects gaffes and goofs in some of the others. She is candid and credible.

Some of the running dialogue in Road was picked up from Neal by Jack early in 1949, such as “Everything is all right” and “Everything was collapsing.” Neal was even more anti-establishment than Jack, and let him know it, remarking that Kerouac’s two incarcerations had not defined him: “[Y]our deep anchor has been this involvement with writing, which, unerringly threw you into the other camp.” That came from jealousy because Neal was also a reader who wanted to write but just couldn’t. Jack generously hoped to liberate Neal from menial work like patching tires in San Francisco so that he might really compose instead of just vocalizing, declaring: “Of all the teachers you have had don’t you think I’d be the hippest?” He offered to show Neal “the way to what you sometimes sarcastically called the ‘world of the big boys.’ […] But once in this world you need not fear the American Gestapo that hounds the American Dispossessed.” Interesting that Franz Kafka doesn’t seem to have figured in Jack’s reading. But who knows?

¤

The last 40 percent of The Voice Is All, as Jack is seeking the right voice and mode, builds toward the completion of Road, though by no means to the exclusion of many other trials and triumphs. Bea Franco, the lovely pixie who appears as the Mexican girl in Road, was part of a travel experience Jack had out west in 1948. When Jack’s story “The Mexican Girl” was published in The Paris Review in 1956, that event finally precipitated publication of On the Road the following year. It had lain fallow for six following numerous rejections, and was once titled ‘The Hip Generation.’ The most important revisions occurred late in the winter of 1950 and in April 1951 when Jack regarded himself as a “lyric poet.” As he presented the long rolled typescript (like Japanese wallpaper) in Robert Giroux’s editorial office, he exclaimed: “The Holy Ghost wrote it.”

After the work was done Jack craved “uninterrupted rapture.” He wrote the first chapter for a sequel to The Town and the City, called La Nuit est ma femme. Then came hospitalization for phlebitis and other woes during the summer. By the later part of 1951, where Johnson’s book ends, Jack had begun writing about Neal again in what later became Visions of Cody (1959), but he was once more actually conflating identities autobiographically. As Joyce Johnson puts it:

Passionate identification drove Jack’s new writing about Neal — as if their two lives had always flowed into one stream, as if they shared the same consciousness and experience that had made them outcasts in America […] as if both he and Neal had come from a place and a time that were steadily vanishing from the American psyche.

Johnson, who is my chronological contemporary but unknown to me, has provided a calm and collected yet gutsy and intense, admiring biography, warts and all. She believes in Jack’s genius and explains how it reached a kind of fruition and apogee at mid-century. If it was the Time of Henry Luce, it was also the Genesis of the Beats. They both got off and had their begats, two modes of telling things about Life.

There are just a few spots where I penciled question marks in the margins, not because facts are wrong but because the phrasing puzzled me. Her prose is especially fine in the lengthy last chapter where her words and his seem to flow together as she describes his experimentation with verbal sketching:

The act of writing requires entry into a meditative state, different from normal concentration, in which the tension between what the writer knows or feels and the peculiar need to put it into words upon a page can be resolved. But sketching demanded something more from Jack — abandonment to a “tranced fixation” on the object, a deeper way of dreaming upon what he saw. “Everything activates in front of you in myriad profusion,” he would explain to Allen the following spring. “You just have to purify your mind and let it pour the words (which effortless angels of the vision fly when you stand in front of reality) and write with 100% personal honesty both psychic and social, etc. and slap it all down shameless, willy-nilly, rapidly until sometimes I got so inspired I lost consciousness when I was writing.”

Johnson then wonders whether there might have been an inherent danger for Kerouac in becoming what William Butler Yeats called, in an essay about modernist, stream-of-consciousness writers, “a man helpless before the contents of his own mind.”

Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando is, among other things, a send-up of biography as a genre, especially long, tedious Victorian life-and-times epics. “It was now November,” she says, recounting an uneventful year in Orlando’s homme-femme life: “After November, comes December. Then January, February, March, and April. After April comes May. June, July, August follow. Next is September. Then October, and so, behold, here we are back at November again, with a whole year accomplished.” Johnson doesn’t get remotely near that nadir. From time to time I felt tempted to turn to the endnotes to check whether it was 1949 or 1950. Chronology matters much less than what bookworm Jack is learning or whom he is loving at the moment.

I must note in passing that in August 1957, when Johnson was preparing her first novel for submission to a publisher, Jack wrote the following: “Your parents oughta be pleased you’re staying in NY. By the way, are they going to let you publish under yr. real name [Joyce Glassman]? I hope so. Your reputation will be no more lurid than Virginia Woolf’s, after all.” Some have speculated that Jack was anti-Semitic. I really can’t say, even though his father certainly was; but some of his best friends and Joyce were Semites. If Allen Ginsberg felt that Jack was anti, it didn’t seem to show. (For Ginsberg’s devotion to Jack, see Patti Smith, Just Kids [2010], 123.)

Johnson’s new book was certainly not pre-empted by the earlier one — the 1957–58 letters with clarifying commentary — nor is the new one any reason to ignore the old. On the contrary, it contains all manner of rich material not mentioned in Voice at all. For a start, here is Jack writing to Joyce from Mexico City in July 1957, urging her (with XXX) to join him there: “Come on, we’ll be 2 young American writers on a Famous Lark that will be mentioned in our biographies — Write soon as you can, this address, I’ll be waiting for your answer—” She mattered to him and he could be supportive.

In early October he flatly declared his aspirations with his whole bared soul hanging out:

These next five years I will be so busy writing and publishing and producing I won’t have time to think about l’amour […] then, when I have a sufficient trust fund built up, I’ll relax and go cruising around the world and turn my thots to love […] and really write my greatest personal magic idea works for Myself.

“WOW,” she responded, and then in a long opening paragraph, she writes exactly what he needed to hear: “Well, the great, happy thing is that you’ve written something. All your talk about not writing anything more worried me. I think you have to write and that you have no choice in the matter.”

The Voice Is All ends where Jack’s journal does, and when On the Road was done. In part, her book seems an extended, in-depth riff on the journals as well as much else from his oeuvre. Voice flows with percussion-like ease. Think Carmina Burana by Carl Orff, that wonderfully sensuous scenic cantata from 1936. Johnson’s warmest assessment occurs in her penultimate section, not a premature climax but a mature assessment:

Jack’s true life novels do contain much verifiable fact, but by the second half of 1951 the truths he would seek to recapture above all would be the texture of his experiences, the feelings associated with them, the Proustian epiphanies he’d had, rather than the precise factual details surrounding each event. The crucial element in his work would not be the invention of plot or the creation of composite characters but the alchemy that turned his memories into art, shaping, altering, and refining the raw material he worked from — all toward arriving at what Wolfe had called “a life completely digested in my spirit."

The Voice Is All feels like a literary act of love and remembrance. Its title, however, is a little puzzling. Is the “voice” referred to literally coming from his vocal cords — he did read very well — or does it mean the eventual achievement of a distinctive literary style in On the Road? If the latter, the point is kept rather implicit. Well, maybe that’s okay. But what exactly was Jack’s “lonely victory”? Eventually getting published? Making it as a Franco-American writer whose first language was not English? Breaking into the The Paris Review which in turn broke the logjam that liberated On the Road to appear six years after its completion? All of the above? Doesn’t much matter, but it means to me that an outstanding book deserved a better label.

¤

During 1963–65 my wife and I lived in Lowell House, one of the neo-Georgian undergraduate residences along the Charles River at Harvard University. One of my responsibilities involved managing a grant from the Ford Foundation whose intended purpose was to bring interesting and distinguished people from many walks of life to the house for two to four days to meet and eat with undergraduates, visit classes or seminars that regularly took place at the house, and give one public “performance” open to the Harvard community more generally. We offered travel expenses and a very nominal honorarium. Guests included Dr. Benjamin Spock, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (defeated by JFK in 1956), William L. Shirer, the extraordinary Berlin Diary (1941) journalist, and Jack Kerouac in late March 1964. Groucho Marx declined my invitation on the grounds that he did not want to lower Harvard’s standards.

Jack accepted readily because he still had many buddies in Lowell (Massachusetts) and figured he would have time to party with them, which he did. (That wasn’t discussed and frankly it really hadn’t occurred to me. I was young.) As it happened, his visit was set for Easter week, Tuesday through Thursday evening. I scheduled him to read or give a talk with Q&A on Tuesday at eight o’clock, following dinner in a private dining room with 12 undergrads and two PhD students in literature. As an instructor I was advising several senior honors theses in history, and draft chapters were coming in to me that week. I think the ultimate due date may have been 10 days later. Most intense phase of the academic year. Time was tight, but it looked doable. When I wasn’t with Jack I would read drafts for quick turn-arounds.

Jack arrived a little before three o’clock on Tuesday afternoon. After we stashed his bag in the Preacher’s Suite (recently so precisely re-lettered as the “Lecher’s Suite” by some anal wise-ass), we chatted for a bit on a low concrete bench in the large courtyard. When I asked Jack what he’d like to do or see before sherry hour with students at five, he swiftly responded, “Let’s have a beer.” I nabbed a tutor and four students for the short walk via Mount Auburn Street through the Yard to the Oxford Grille.

Sitting at a spacious round table, we finished a pitcher of beer fairly swiftly and I ordered a refill. As I recall, no chips or nuts. Just the beer. Seconds after it arrived Jack picked up the well-topped pitcher and with a quick twist of his wrist turned it upside-down, brazenly proclaiming, “Let’s turn one over for Omar Khayyam.” I still have no clue what that meant. But it certainly got our attention — not that we were bored. Needless to say, well-chilled beer flowed onto all of our respective laps. I paid the bill and we strolled back to the house sheepishly, looking like seven guys who had soiled themselves.

We showered, dressed, and reconvened in the junior common room for sherry with several house tutors and a group of undergrads. We proceeded to dinner at six, Jack having had three or four topped-up sherries. He ate very little dinner (we didn’t force-feed guests) but imbibed considerable wine. He was 42 and I was 28. I assumed that he could deal with alcohol, but this wasn’t an optimal start.

When we got back to the common room at eight, the place was jam-packed with roughly 250 people — students, faculty, staff — and they seemed to be hanging from the rafters. Many of the people in the front row were women with their legs crossed. (Few women wore slacks or denims then, and never in the evening.) Upon entering Jack surveyed the scene and exclaimed, “Nice legs.” Easing to the center where I would introduce him, he looked around at the crowd (they were competing for the waning oxygen in the room), and then said very audibly to no one in particular, “Nice tits.” (The only press coverage that I am aware of appeared in the Harvard Crimson on March 25, 1964, a badly muddled account reprinted in Empty Phantoms: Interviews and Encounters with Jack Kerouac [2000], edited by Paul Maher Jr.)

I took his arm and offered to walk Jack to his suite but he said “No” in a strong voice. “Do you have Emily?” (By the way, I don’t recall that he had brought a book or any papers to read from. That should have been a clear clue.) I assumed that he meant Emily Dickinson and I happened to have two binding-defective volumes of her poems (hence cheap) in my office, recently edited by Thomas Johnson for the Harvard University Press. I suggested that Jack come with me because I really didn’t want to let him out of my sight. He said “No” again in a loud voice. “I need to take a leak. You get Emily and I’ll meet you back here.”

He did and we did and he read Dickinson splendidly and with feeling. He knew exactly which poems he wanted, flipped pages and found them handily. After about 25 minutes, however, he looked very much like he was going to pass out, perhaps more from hunger than alcohol. I offered to escort him to his suite and he agreed that that would be okay. The crowd expressed both disappointment and hearty appreciation, pari passu, we made our way uneventfully, and that was that for the day. But it actually wasn’t quite so for Jack.

The next day David Kalstone (soon a literary critic and professor of English at Rutgers) took him to breakfast and later to a sophomore seminar on Shakespeare, where Jack behaved and interacted wonderfully. A very model of the visiting star he was meant to be. But shortly I learned that the previous night some of his high school buddies, alerted about the visit ahead of time, of course, had picked him up and taken him to Central Square for drinks and to visit a whore. He became too soused to perform and was returned to the house to sleep it off.

On Thursday Jack participated in a junior seminar (I’m pretty sure it was) on American literature with Albert Gelpi (now professor emeritus at Stanford). That, too, went fairly well and it looked as though the visit was turning out quite fine after all. I just needed to escort Jack to Logan Airport for a flight to LaGuardia on Eastern Airlines, and from there he would be conveyed to Northport on Long Island where Jack, now twice divorced, was living with his beloved Mémére who had never stopped infantilizing him — a troubling major motif in Johnson’s biography as well as in others. She just would notlet go of him — her daughter had another troubled marriage and lived in North Carolina — and Jack loved mother Gabe’s cooking. The wild man of letters was her baby boy. As he wrote to a friend in 1943, “My mother is essentially a great woman.”

So we reached Logan easily enough on the trolley, but because it was Maundy Thursday and so many people were traveling for Easter break, the crowds were dense and lines for the Eastern shuttle were ropey long. As we stood in line Jack turned to me and said, “Mike, you’ve got me here and you’ve got chapters to read for your kids. You should go back to Lowell House. I’ll be fine.” I said “Nope” twice but he vehemently insisted. So I left. Maybe that was a mistake, but maybe not. Turns out he had one more plan, as he did for Tuesday night, so that he could make sure a sense of scandal would scent his visit. This suited him.

That night, sometime after two, Lowell House was stark still and my wife and I were profoundly sound asleep in our suite on the bridge that spanned the passageway between two courtyards. Suddenly an enormous five-alarm roaring bellow rang out from the small courtyard below our bedroom: “Fuck you, Mike Kammen.” By the time I got a robe and slippers on and got down the entryway stairs, he had vanished. Not a trace, not even a whisper. I learned later that he caught a cab from Logan to Lowell House and after serenading me went to Lowell. Thence his buddies drove him to Manhattan where they went to Birdland, one of Jack’s favorite nightspots for jazz and bebop. After that, he returned to Northport, 40 miles from Manhattan, and the quiet life with Mémére — for a while. That would mean a writing stint.

Nine days later I received a letter from Jack, a revealing apologia, for lack of a better word. It’s never been published:

…………………………..

April 5, 1963 [1964]

Dear Mike

According to what I’d told my mother on the phone, that I’d made a great scandal of myself at Harvard, she was relieved and gay when she read your letter [of thanks for the visit]---As for the airplane, Mike, do you realize that those hundreds of people were waiting in line for Easter weekend and blah, I felt too good to wait around and BESIDES (and this is the point) I really wanted to go to Lowell Mass. and continue my researches on what you must admit is a city I’ve written about in great enough degree to warrant my going there when I’m only 24 miles away----So I went, in a cab driven by a nice Greek immigrant, to this Greek town, he even came into the Greek hangout with me when we got there---And there were other readings and stuff there, by the way, for local young interested including a divine 16 year old blonde who was however chaperoned tho I kept yelling to the chaperone I was too old even for HER----That was fine, and I saw all the old French Canadians of my childhood----But the worst part was driving from there with 2 friends straight to Birdland in New York to hear jazz and then go see the fools and maniacs of Greenwich Village etc. ending I finally staggered home all dirty and broke and coughing but now, Sunday night, I’ve recovered and I hope you are well also---Finding for instance, in my piled up fan mail, at least 3 girls wanting to know if I’m “really me.” ---(Thank God they’ll never know what it is to be really me, i.e., insane, or near it)---And Mike I told Al [Gelpi], in a letter for instance tonight, I didn’t expect you to be able to be with me any more or any less because you had your work to do----If I were a teacher, same thing, I’d have to attend to my appointments etc. but being that I was just a happygolucky visiting talker, okay----All I had to do was talk everywhere with everyone everytime, in the style no doubt that Dylan [Thomas] and Brendan [Behan] and probably Faulkner employed when they visited campuses---So thank you for your beautiful attention, and David [Kalstone] too, John Lewis, O’Grady, (O’Grady the Visiting Eye), of course Al----And incidentally Prescott Townsend, if you know him or seen him---As I came back a few nights later and “lectured” a creative writing class somewhere, was it Boston? I don’t know---But I had my gang from Lowell with me (Lowell Mass.) and we were actually looking for you at dawn, I think---Just as well, of course----

But will see you someday---Maybe at Oxford, not the Grille.

Yours also,

Jack

Any news from Mao?

…………………………..

On April 22, 1964, Jack wrote from Northport to Stella Sampas, sister of Sebastian Sampas, Jack’s beloved boyhood friend who died in the Pacific theater during the war — a devastating loss for Jack. After explaining some convoluted transactions among his Lowell friends, he wrote:

Believe me. I’ve suffered so much now from my frantic imagination, of which I am the victim, I sound now like Billie Holliday when I sing, or worse, like Homer. I hope Charles Scoopy and Pertinax weren’t mad about Harvard, it was bad enough without journalists and photogs from Lowell to record it. I told everybody anything that came to my mind and it doesn’t matter what I said. I’m like Brendan Behan and Dylan Thomas, determined not to have monuments built for me in Dublin or in Cardiff. I’m an old time French farceur, which is a French word meaning honest goof-off. […]

I am amazed. I finally got Mozart’s REQUIEM off the radio last night: this I’ve been waiting for years: a tall man in black came to Mozart when he was dying and asked him to write a Mass for a dying noble; Mozart wrote it, thinking the dying noble was himself; he died before he finished it: turned out it was a big joke played on Mozart by some nobles: but Mozart died, was buried in a pauper’s grave, and today the Requiem he wrote stands as the greatest Mass ever writ.

Jack

(Jack to Stella Sampas, April 22, 1964, in Jack Kerouac: Selected Letters, 1957–1969 [1995], edited by Ann Charters. Jack married Stella in 1966.)

So, for better or worse, Jack had the notion firmly planted in his brain (or else a post-hoc rationale) that Dylan Thomas, Brendan Behan, William Faulkner, William Styron, and others behaved in certain ways when they visited college campuses, with the help of booze and acting out, improvs basically involving liquor and semi-anti-social behavior. True to form, they mostly did so and gave students a Wow.

I don’t believe that his funny/fierce “Fuck You” indicated personal hostility toward me, though I could certainly be wrong. The obscenity reflected his sense that Harvard, sherry, orderly courtyards, classes, and common rooms epitomized the establishment “rose bushes” that had always made him feel uncomfortable and perhaps guilty — a traitor to his class. Ditto turning over the gallon of beer. He established at the outset who he was and how he intended to play his cards, and ended with trump.

¤

When it comes to Jack Kerouac, I have a simple supposition. As Joyce Johnson points out numerous times in The Voice Is All, believe it or not, Jack was fundamentally a shy man (see pages 37, 41, 47, 61, 73, 143, 280–81). Emerging from a working-class family of Breton descent in Lowell, Massachusetts, his parents having limited English, especially his mother, and now coming to Lowell House to schmooze with Harvard kids and give a public reading, this was a very big deal to him — a moment to remember, if he could.

I suspect that he soused himself with beer, dry sherry, and wine between four and eight o’clock that Tuesday in order to psych himself up for what could have been a triumphant occasion, plain and simple, but turned out to be a tragicomic circus. By the time he finished reading Emily Dickinson’s poems, however, his audience at least understood that he really was a man of letters.

And by gum, he truly was. Seven years earlier he sent a sonnet in a letter to Joyce Johnson. Presumably the sonnet was not only for but also about Joyce, who was 14 years his junior:

A POEM FOR EMILY

Sweet Emily Dickinson

who played with your hair?

who counted the pimples

on your moonlight chin?

who wiped away the smut

of your disregard of natural

phenomena in hairy men?

who taught you love of cock?

who taught you cunt?

O sweet Emily, if death

stopped on your proud door,

did I, the lily weep?

did I, the marble sarco

phagus, bleed iron chocolate

tears? Meet you in the

c h u r c h y a r d

I also suspect that coming to Lowell House may have revived his highly ambivalent feelings about what he often called “white ambition,” prompting him to wonder whether he really wanted to be “respectable” by entering and participating in a stuffy lifestyle — an anxiety that hit him hard, for example, after he took Robert Giroux to Denver’s Stapleton airport at the end of their trip west in 1949. (Emily Dickinson was prime among the poets Jack had read that summer while he was waiting for a ranch to somehow materialize in Colorado.) His aspirational world was literary, not social. He was all about not being too prim, proper, and prosperous — not having rose bushes. As Johnson observes in a fine phrase, he doubted whether “happiness was good for his art.”

In June 1964, less than three months after Jack’s visit to Lowell House, he saw Neal Cassady for the last time when Neal came to New York City with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters. I find considerable confirmation that by March 1964, when I encountered Jack, he was visibly wearied of life, and his drinking continued to escalate. He was well into what Johnson calls “the last sad decade of his life.”

In June 1952 Jack wrote to John Clellon Holmes from Mexico City where he had recently finished both Visions of Cody and Dr. Sax. He announced his discovery of what he called “wild form”: something that was taking him “beyond the novel and beyond the arbitrary confines of the story into realms of revealed picture.” He wanted to “set down everything I know — in narrowing circles around the core of my last writing.” But then, without specifying what he meant, but perhaps not needing to for a friend who knew him well, this realization tore at his very being: “I love the world […] but at this time in my life I’m making myself sick to find the wild form that can grow with my wild heart.” Four years later, in Visions of Gerard, a book about his older brother who died at eight with Jack four, he declared: “I’ve grown sick in my papers.”

Jack died in St. Petersburg, Florida, on October 21, 1969, from massive internal bleeding caused by cirrhosis of the liver and related causes. He is buried in the Edson Cemetery in Lowell, Massachusetts. Excessive alcohol and drugs snuffed the life of a remarkable mind and its literary quest. He really was a quester, too often perceived in popular culture as a simple jester. He was ultimately a serious man with a cerebral gift that he sought to mine from an early age.

He also had a great gift for friendship. His buddy groups growing up in Lowell were called the Young Prometheans in the Forest of Arden. At Columbia and in Morningside Heights he was at the heart of the Libertine Circle, everyone having sex with nearly everybody else, but hashing out ideas and writing as well. Next came a new but linked group centered at the apartment of John Clellon Holmes and his sister Marian located on Lexington Avenue and 56th street; and finally there were Bill Burroughs and Joan Vollmer, a dysfunctional couple, brilliant but rebellious, refugees from the law in Texas and Mexico where Jack visited and lived a somewhat different sort of life, but not really. More drugs and booze, of course, but he did write there.

Jack’s affective bonds with Neal and Carolyn Cassady, a shared woman with poise and a certain classical beauty, and always with Allen Ginsberg and his friends, were profound but destructive and self-destructive. Happily, Joyce Johnson only uses the last hyphenate twice, even though it is endlessly, tragically applicable.

Early in November 1957, with On the Road done, when Jack casually called it “only a light comedy,” Joyce responded that “they’re just about the hardest thing to write. And you are a poet, always a poet — ON THE ROAD’s a poem as much as THE SEA IS MY BROTHER (that’s beautiful!).” Bob Dylan once remarked that, “I read On the Road in maybe 1959. It changed my life like it changed everyone else’s.” Joyce Johnson’s as well.

Late in 1957 Jack sent Joyce one of his most exuberant letters. (When he was down, he was really out; but when he was up, he used all caps and oozed enthusiastic self-confidence.) Let’s read the beginning and then the middle of a longish letter. Just two juicy sentences:

Lissen Joyce, long silence because writing new novel which is not memory babe at all [a different project], but the DHARMA BUMS, greater than On the Road and however only half finished & right in midst of my starrynight extasies contemplating how to wail & finish it I get big phone call poopoo from Sterling Lord [agent] says Millstein arranging for me to read my work over mike in Village Vanguard nightclub for salary per week so will do for money and for excuse to come back to New York [from Orlando which he did not like — found it very dull].

And then, explaining his disinterest in money and jobs as a serious priority, as opposed to writing:

I’m not money mad, that’s why I’m an artist. […] That’s why I am and will be always a bum, a dharma bum, a rucksack wanderer.

¤

“Who is his companion now? He hath every month a new sworn brother.”

— William Shakespeare, Much Ado about Nothing

Which brings us to the first (and only) filmed version of On the Road. Does that astonish you? It certainly amazed me because if ever a novel felt fairly obvious for a wooly Hollywood take, this one does. Just imagine Peter Fonda and Dennis … Oh, they already did that one? Okay. Well, there were/have been various versions of Road imagined and two were even cast, but the production money never materialized. So it was left for Francis Ford Coppola to outsource the book to a Brazilian/French-Canadian team that filmed it in Montreal with footage in Gatineau, Quebec, and scenes in and around Calgary (subbing for the Denver area), New Orleans, San Francisco, Arizona, and Mexico. It was initially released at Cannes on May 23, 2012, and in the United States on December 21.

If I hadn’t recently read The Voice Is All and reread On the Road, I believe I would have been baffled and bored (it’s too long), but under the circumstances I felt engaged and understandably kept trying to figure out whether it was “right.” It is and it isn’t. The first fifth or quarter seemed surprisingly faithful even if Sal Paradise/Jack or else Carlo Marx/Allen Ginsberg (we see them from behind) tried to stand on his head in a fairly sizeable mud puddle which is not the way Jack would have done it, or why. Doing so seems silly if not stupid in the film; yet Kerouac did stand on his head when he was excited or felt muddled and meant to clear his mind.

Jack enjoyed being outrageously naughty, as we have seen with that pitcher of beer at the Oxford Grille, and he envisioned Sal Paradise being just that way, in an impulsive sally that isn’t realized in the film. Here is a prime example from On the Road that’s an ignored opportunity in the film. Sal and his buddy Remi Boncoeur have broken into the barracks cafeteria at night:

The barracks cafeteria was our meat. We looked around to make sure nobody was watching, and especially to see if any of our cop friends were lurking about to check on us; then I squatted down and Remi put a foot on each shoulder and up he went. He opened the window, which was never locked since he saw to it in the evenings, scrambled through, and came down on the flour table. I was a little more agile and just jumped and crawled in. Then we went to the soda fountain. Here, realizing a dream of mine since infancy, I took the cover off the chocolate ice cream and stuck my hand in wrist-deep and hauled me up a skewer of ice cream and licked at it. Then we got ice-cream boxes and stuffed them, poured chocolate syrup over and sometimes strawberries too, then walked around in the kitchens, opened iceboxes, to see what we could take home in our pockets.

Yet the movie is ambitious. It captures the restlessness of the real characters, who are essentially seekers in various ways, and their “beatness” comes through to a degree, though it’s much more their wannabe-beatness that emerges. The city scenes are especially credible as context, and the countryside is pretty fair. There is considerable attention to detail but there is carelessness as well. If Sal Paradise is meant to be Italian in the book, then the single allusion in the film to a French-Canadian baby being possibly fathered by Sal/Jack makes no sense at all. Let’s keep the ethnicities straight, and not confuse them. The movie is confusing enough as it is.

Minnesota-raised Garrett Hedlund does a very credible job as Dean/Neal Cassady. He conveys the sexual energy of Dean as a grifter who uses people the way he uses cars and cash — altogether expendably. I feel that his ephemeral sexual relationship with Carlo Marx/Ginsberg (Tom Sturridge) has been made simultaneous in time rather than sequential in terms of other relationships, all in the interest of condensing events — but perhaps that’s too picky. Neal was an omnivore when it came to sex, but mainly for instrumental ends. And, like Jack, he wanted to please the people he really admired. Both were basically ladies’ men but both had sex with Ginsberg early on. Or let him do them.

Yorkshire-born Sam Riley is either miscast or misdirected as Sal, perhaps both. He is too much the voyeur in this visualization. He is accurately portrayed as a young writer in search of experience. He needs material to write about. But he is not interesting. Why, near the very end, would a weary and sad Dean wend his way all the way across the country to connect with this guy once more?

"Neal and Jack," by Carolyn Cassady. From "Off the Road: My Years with Cassady, Kerouac, and Ginsberg" by Carolyn Cassady (Black Spring Press)

Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

Sal is so passive that the buddy aspects are sometimes incomprehensible. It’s true that Jack was intrigued by Neal’s irrepressible spontaneity and therefore made him the star ofOn the Road, but Kerouac too was a wild and crazy guy. I missed the man who could turn a large and full pitcher of beer upside down at a table for seven in Cambridge.

Kristen Stewart, who was just 20 in 2010, does well enough as Marylou/LuAnne, a wistfully wanton 16-year-old, and Kirsten Dunst seems just right as Camille/Carolyn Cassady. Jack’s mother and muse, however, who becomes his Paterson, New Jersey, aunt in the book, is utterly nondescript, a nonperson, which totally belies her importance in his life.

And Jack’s wonderfully piquant episode with the Mexican girl he meets in California, so vital in launching On the Road as a Paris Review story of its own in 1956, gets woefully foreshortened so that its sweet significance for him gets entirely lost in a pretty cotton field and a barren tent for lovemaking. In the book they make love beneath a menacing tarantula resting on a barn rafter — another great opportunity missed. Even an indie could make a fake tarantula to oversee sex.

Finally, almost, a well-thumbed copy of Swann’s Way by Proust makes an appearance five or six times as Dean’s carry-on — the one and only work that does appear as an actual book rather than donnish rows of colorful spines on bookshelves. I would have chosen Dostoevsky instead. But, as it happens, 2013 marks the centennial of the first edition of Swann’s Way, a book manuscript that Gallimard rejected, just as Jack’s manuscript was initially rejected by Harcourt. The marvelous Morgan Library in New York City currently has a gem-like exhibition devoted to Proust’s classic, which he then arranged to self-publish. Kerouac did not, though he had to wait six years, and his book has done very well ever since.

In the Library of America edition of On the Road (2007), the texts of his various Road Novels are followed by 55 pertinent pages from Jack’s journals. They are juicy, lucid, rich and raw, mainly covering 1949–1954. Here is an entry from May 1949 as Jack is en route from New York to Denver: “I had intense visions of the sheer joy of life […] which occurs for me so often in travel, coupled with a grand appreciation of its mystery, & personal wonder.” It’s precisely Jack’s joy and visions as well as the mystery and wonder of it all that are largely missing from the film. There is virtually no exuberance. He’s too often tentative, mystified, and pensive to be persuasive as Sal Paradise. I kept waiting for the intensity of his experiences. Here’s a sample from the journals:

San Diego rich, dull, full of old men, traffic, the sea-smell — Up the bus goes thru gorgeous sea-side wealthy homes of all colors of the rainbow on the blue sea — cream clouds — red flowers — dry sweet atmosphere — very rich, new cars, 50 miles of it incredibly, an American Monte Carlo — Up to LA where I dig city again, to Woody Herman’s band on marquee — Get off bus & walk down South Main St burdened with all pack and have jumbo beers for hot sun thirst — Go down to SP railyards, singin, “An oldtime non-lovin hard-livin brakeman,” buy wieners and wine in Italian store, go to yards, inquire about Zipper [Zephyr, a train]. At redsun five all clerks go home, yard quiet — I light wood fire behind section shanty and cook dogs and eat oranges & cupcakes, smoke Bull Durham & rest — Chinese New Year plap-plaps nearby —

Now that’s intense, even so when Jack is alone and Neal or Allen are elsewhere. In the book Sal does say at one point, “This can’t go on all the time — all this franticness and jumping around.” When Jack says “I was beat” (and he does often) he means tired, road weary, and broke.

Dean/Neal frequently gave the gang directions because he’s the head scout. At one point they are moving all of Sal’s aunt’s (read: mother’s) furniture from Virginia back to Ozone Park in Queens. Dean/Neal issues orders:

Oh man, we must absolutely find the time — What has happened to Carlo? We’ll all get to see Carlo, darlings, first thing tomorrow […] We’ll put everything in the back seat, Mrs P’s furniture, and all of us [four] will sit up front cuddly and close and tell stories as we zoom to New York. Marylou, honey thighs, you sit next to me, Sal next, then Ed at the window, big Ed to cut off drafts […] and then we’ll all go off to sweet life, ‘cause now is the time and we all know time.

Perhaps the words Jack chose to italicize vindicate the director’s choice of Proust’s tome as a display piece. Yet the characters in On the Road are perhaps too young to truly know about time. Sal/Jack is just 25 and convincingly naïve and inexperienced in the film. Like Jack, he is also somewhat shy. At the conclusion, however, Sal appears as a Brooks Brothers preppy, which he actually was for one year after high school — anything but “a bum, a dharma bum, a rucksack wanderer.”

Shares