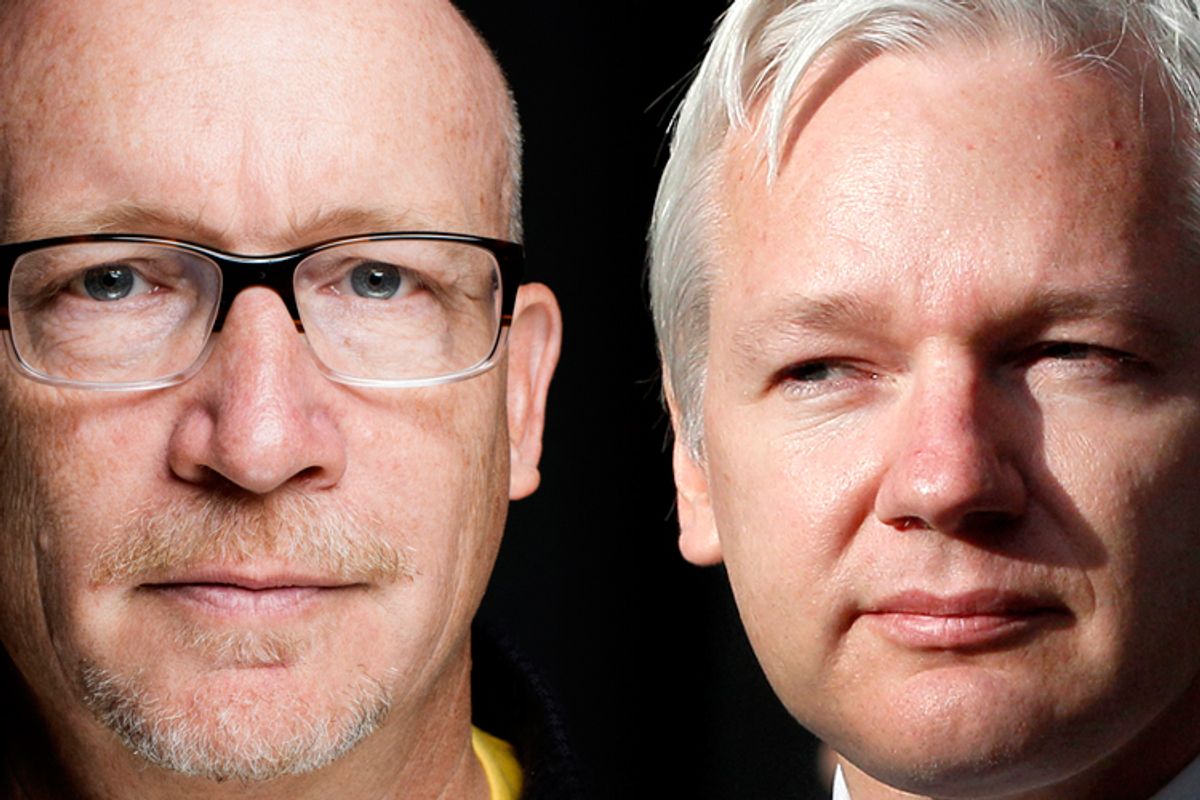

So Alex Gibney, the Oscar-winning director of “Taxi to the Dark Side,” “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room” and many other political and social documentaries, has made a fascinating film about Julian Assange and WikiLeaks that has already pissed off a lot of people on the left – and is about to piss off a bunch more. “We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks” portrays the Australian hacker-hero Assange as a flawed and complicated figure. As British journalist Nick Davies puts it in the film, the same extraordinary personality who created WikiLeaks is also the one who destroyed it. On one hand, Assange has led the fight for freedom of information in the asymmetrical conflict between the world’s citizens and fearsome Goliaths like the CIA and the Pentagon. On the other, he has allowed his alarming personal failings and his persecution complex to become much too large a part of the story, and has succumbed to what one source in the film calls “noble cause corruption.”

Many will argue that one thing is not like the other, that the greater campaign that WikiLeaks has led against the sinister forces of government and/or corporate secrecy is too important to be derailed by one man’s personal misdeeds. Of course that’s true, in the larger scheme of things. Gibney defends his approach eloquently in our interview, and I would urge people to see this film before they make assumptions about what argument it makes or whose side it’s on. One could probably summarize its Assange analysis this way: The guy has done some extraordinary things, but he’s no candidate for sainthood -- and too many people on the left are ready to embrace heroic Joan of Arc figures, and to see the world in terms of a binary struggle between good and evil. It does no one any favors to pretend that the charges against Assange are not troubling, or that he has not insisted on politicizing them rather than dealing with them privately and decently, or that he and many of his supporters have not reacted to them in shameful and misogynistic fashion.

But Assange himself is only one player in “We Steal Secrets,” which features interviews with intelligence insiders, journalists and many of Assange’s former colleagues at WikiLeaks. The film’s one true hero might be Pfc. Bradley Manning, the U.S. Army intelligence analyst who literally sacrificed himself, and now faces the prospect of many years in prison for leaking an immense trove of material on America’s near-disastrous conduct of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Manning’s sexuality and gender-identity issues become part of the story too, because (Gibney argues) they symbolize on a personal level the changes he was trying to make happen globally.

“We Steal Secrets” is likely the most intricately argued and carefully constructed of Gibney’s films, a masterful and thought-provoking deconstruction of recent history as well as a study of human nature. Whether or not you agree with his take, it results from intensive research and much debate, and is not an irrelevant distraction or a work of covert CIA propaganda. I recently met Gibney for lunch in New York.

Alex, one thing I notice about this movie is that you don’t try to tell Julian Assange’s life story, in that classic TV-documentary way. We get some background about him -- including the intriguing suggestion that he may have hacked into NASA computers way back in 1989 -- but not much.

We had it in there. In the three-hour-and-thirty-minute cut, it was there. We went to Magnetic Island in Australia [where Assange spent much of his childhood], but it became one of those things where the more you include all that stuff, the less you can dig deep into specifics. And then there’s Bradley Manning. Bradley Manning, along the way, became much more interesting to us.

So you did not know, going in, how important his story would become.

No, because when we started, only the first batch of chats [between Manning and American hacker Adrian Lamo, who eventually turned him in to authorities] had been released, and then there was a second batch that gave you a much fuller portrait of him. At least initially, we were terrified of the idea of having a character that we couldn’t talk to, who only existed in the form of chat transcripts! We hadn’t decided that we could just go for it.

Just to be clear, the texts of the chats we see in the film are for real, right?

Yeah. I mean, obviously, we’re shortening and making elisions here and there, but every word you see on the screen is Bradley Manning’s.

Talk a little bit about Manning’s gender-identity issues, and why that was important material to include.

Well, the gender identity stuff came out pretty early, in the first batch of chats. And, frankly, the Army tried to make hay of that and people in the Obama administration were leaking material about him that –

“This is a confused person.”

Right, a confused, fucked-up person who of course is gonna do something like this because he’s just messed up. And there was a certain amount of internal debate on our team of how much of that material we should include.

Whether it was relevant, right. What did you think about that?

Ultimately we thought there was a mystery to the Manning story that was profoundly relevant to the WikiLeaks story. It seems like he leaked the material and leaked it effectively where his identity might have been kept secret. So why did he reach out to Adrian Lamo? Well, once you go down that road, then you see something – then it’s more important. He reached out to Lamo in part because Lamo was bisexual and also a hacker – and even in the chats, you could see that Manning knew about it.

And then it raises the question, although it’s not definitively answered, about the relationship between the source and the publisher. We now know a little bit more since Manning spoke to the court [at his trial], where he says he thought he invested far more in that relationship than Assange did. When I started the film, I thought it was about two things: a David and Goliath story, and this new technology, this new leaking machine. But you realize that the leaking machine is not so powerful in technical terms, because you can trace the computer either at the tail end or the front end, but also it turns out there’s this human component that’s part of leaking that’s all about the trust between the source and a reporter, the source and the publisher, and a need to communicate. That’s the interesting thing. Manning needs for people to know that he did this thing. He needs to be recognized. “I am somebody. I need to be recognized as somebody having done something.”

I was wondering about that. It struck me that there was a semi-voluntary aspect to his going public.

Oh, it was entirely voluntary. Well, Lamo lies to him and says “Trust me, I’ll keep this confidential.” But Manning – that’s the thing about secrets. They’re very hard to keep. And once you tell them, all you have is the trust of somebody else at the other end of the secret, and he was trusting somebody he’d never even met. Which of course is the intriguing thing about the Internet to begin with. Some of these chats get very intimate. And Manning was lonely, he was isolated, he was not very macho in a macho culture, so all that stuff about his identity gets into that very idea of making a difference. Well, he was making a difference politically, but he was also in the process of making a difference in his own character. Even a physical difference – he was taking hormone therapy.

And this was in the middle of the Don’t Ask Don’t Tell era.

Yes, of course. That makes it a more important consideration, because a lot of this stuff now wouldn’t be as much of an issue. But in that period it was DADT. And at that period they were making more accommodations for him in the military, because he was good. He was smart. They needed bodies. And they needed smart bodies. We don’t spend a lot of time on it, but it tells you something about the selection process in the military. There are two wars going on. You need bodies. You need smart bodies. They were reluctant to discharge him. He went to the discharge unit, and they could’ve flushed him out, but they didn’t. They were like, “Well, this guy’s pretty smart.” His immediate superior said he was the smartest guy in working with computers that he’d ever seen.

Well, one of the key elements of this film is that you argue the personal stuff can’t really be separated from the political questions. So you include issues about Bradley Manning’s sexual identity and you spend a fair amount of time on the sexual misconduct charges against Julian Assange. And I assume Assange’s defenders are not going to be happy about that.

They’ve already expressed that antipathy.

They say that you’re trivializing the issue. Is that it?

Correct. Or these have nothing to do with larger political issues, which I really don’t agree with either. For instance, with Manning: I think the key thing is, how are we to understand the mystery of why he leaks to Lamo? And that takes you into that territory pretty quickly. And also the fact is as that most whistleblowers – and I got in a little trouble for this, as if I was generalizing – are not conformists who are entirely comfortable with their culture. They tend to be alienated from the folks around them.

So there’s that. In the case of Assange and the sex stuff, I didn’t go there initially. But ultimately he’s the one who makes the connection between that stuff and the transparency agenda. Once he goes there, it’s important. Because, first of all, he’s the one that becomes hugely famous out of this, and second of all he’s the one who insists that it’s political. He does it slyly, by saying, “I’m not saying it was a honey trap. I’m not saying it wasn’t a honey trap.”

I feel like that was the moment in the film where I started to lose respect for the guy. Because that’s such a devious-politician thing to say.

Of course! Of course! It’s straight out of the CIA handbook. Or it’s straight out of the political smear handbook. And that’s where he begins to take on the coloration of those he seems to despise. I think character has a lot to do with it. Because at the end of the day – you know, the WikiLeaks paradigm supposedly has nothing to do with personal issues, it’s all mechanical. Well leaking, it turns out, is not a mechanical process.

That concept of a “leaking machine” seems so appropriate to Assange’s personality. He comes off in the film, at least at first, as this disinterested, almost technocratic person who is taking on these much larger institutions –

In a way that you admire, and I still admire. I remember thinking for the first half of the film, “Sign me up for the Julian crusade.”

Yeah, me too. The concept he brings up, which has become so powerful for me that I’ve used it over and over, in conversation and in print, is about the asymmetrical nature of the world. And one manifestation of that is disconnected individuals using the Internet to release these vast troves of information, opening the vaults of the most powerful government on Earth. And the response is also asymmetrical. You have these people saying Julian Assange or Bradley Manning should be droned, instead of talking about the large-scale murder and torture and corruption that was exposed.

Hello? It reminds me how, in the wake of Abu Ghraib, there were a number of military people saying it was just shocking. Those pictures – if we could keep these military men from passing on those pictures! The concern was, “Oh, if only we could’ve kept it secret!” Not about our soldiers running amok needlessly torturing Iraqi prisoners. That was not the concern. In fact, Michael Hayden, who was head of the CIA nuder Bush, told me, “Of course you had to talk about Abu Ghraib” – meaning you journalists – “but those pictures, they give comfort to the enemy.” Well, I suppose they may have given comfort to the enemy, but at what point do you say, OK, so I guess corruption’s off the table, because we can’t ever criticize ourselves, because we might give comfort to the enemy? Which gets right to the point of what’s happening with Manning. He faces charges of aiding the enemy, which is a capital offense. Anything that might be critical of the United States and give comfort to the enemy is a capital offense. Terrifying.

Let’s get back to Assange and the sex charges, because that’s gonna be Kryptonite to a lot of people. Am I correct about what you hint at here – that this guy may have a pattern of having sex with women and intentionally damaging condoms so they become pregnant? I mean, that’s the suggestion.

It’s suggested. I don’t know that to be true. I know that a number of people have suggested that to me as something very real: He likes to spread his seed. But the purpose of including that suggestion was not to say that it’s so, but simply to say that this may be a serious matter, and can’t be passed off as something that is simply trivial. It isn’t jilted women, or women who became jealous of each other, and, as Julian says, “got into a tizzy.” So the purpose of showing some of the leaked material – ha! It’s funny how the word “leak” crosses over in this instance! – the leaks of the police report and also the stuff about his seeming need to sow his seed, it just raises a level of bad behavior, shall we say, that is not improper to investigate.

I’ve already gotten into a dustup about this. The most complete record of this is an exchange I had with John Pilger of the New Statesman, where he came out and attacked my executive producer Jemima Khan, who wrote a piece coming out of Sundance, and I then took it to him on this issue of Sweden. He said, “Look, get over it. It was consensual sex, end of story.” But there was a guy in Canada who went in jail for two years, I believe, because his girlfriend said while she was happy to have sex with him, she didn’t want to get pregnant. And he methodically started putting pinholes in the tip of every one of his condoms until she got pregnant, and spent two years in jail for that. Even the British court found that the allegations against Assange, if proven, would be crimes in the U.K. as well as in Sweden.

To play devil’s advocate and take Pilger’s side for a minute, the response would be that you’re essentially lending aid and comfort to the enemy, so to speak. You’re muddying the waters around the big political questions of Assange and WikiLeaks, and essentially using your skills and influence to make him look bad on an issue that is simply less important than the crusade for freedom of information. So it no longer looks like a clean fight between the forces of good and the forces of evil. It becomes a murky, personal matter where there’s no right and wrong.

Yeah, but I guess you have to unpack that. First of all, the whole film is about, in a way, whether the end justifies the means? If we think that Julian is good, do we have to ignore all his bad behavior, because otherwise his enemies might get comfort? That sounds like the United States government’s argument. That sounds like saying, well, we should muzzle whistleblowers, because that’ll give comfort to al-Qaida. It seems like at some point you have to believe in the truth or not, end of story. Secondly, at what point is this guy above the law? Is it OK, because Julian Assange is Julian Assange, fighting the good fight, that he can transgress the rights of women in Sweden, if that’s the case, and not be held to account? And you have to say, no, he can’t be above the law.

And the last thing about it is that Julian himself is the one who conflated the issues. He could’ve said early on, “This is a personal matter, I’m gonna deal with this as a personal matter. It has nothing to do with WikiLeaks.” But intentionally, from the get-go, he said, “No, this is a part of the transparency agenda, because this is what my enemies are doing to discredit me.” So that’s where I have to go, wait a minute, we’ve got to investigate this and see if there’s any evidence to suggest that these women are working for the CIA, or that they’re gleefully trying to use this in order to extradite him to Sweden so they can send him to Guantánamo.

There’s a lot of smoke about that, and it is true that there’s a grand jury investigation into Assange. But his intent, I think, which is where I part company with him, is to say, “I am good, I fight for truth and justice, so ignore this stuff.” There’s a couple of Wizard of Oz moments in this, the peeling back of the curtain, and this is where Julian is saying, “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain,” and the State Department was saying the same thing when WikiLeaks put out the cables. So that’s where I think this tribalism has an unfortunate cast.

You can see something important that Anna [one of Assange’s Swedish accusers] says in the film. We show the protesters chanting, “Free Bradley Manning, free Julien Assange,” and she says: “They’re acting like there’s an equivalent thing going on here. It’s not equivalent.” Julian would like us to think that it is, that he’s a prisoner of conscience. But Julian put himself in the Ecuadorian embassy, Julian actually got pretty good due process in the United Kingdom.

Now, I was convinced, when I started the film, that the whole Sweden thing was going to be a CIA plot. I couldn’t prove it, but the timing seemed so exquisite, and everything around it just seemed so – I was just convinced that it was bullshit. That it was designed to take him out. But when you actually look into it, that simply isn’t the case, and there’s no evidence, in any way, shape or form, that the Swedish government is acting on instructions from the United States.

You worked very hard to get him on the record in the film and it didn’t work. There are somewhat alarming suggestions about what he asked you for. Tell me about your face-to-face meetings with him.

I met him, I think, three times face to face, and we had a lot of intermediaries trying to work it out. The first time I met him, I really liked him. He was in the Frontline Club in London, where a lot of the film takes place. So I met him there, and I liked him. Then I went to his 40th birthday party, and the invitation, by the way, made it clear to people like Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, who were invited [but did not show up], that there was a strip nearby for a private jet, should they desire. And WikiLeaks reached out to me to ask if I’d pass an invitation on to Eliot Spitzer [subject of the 2010 Gibney film, “Client 9”].

And then I had a six-hour meeting, which I referred to in the film. It was late in the day – my executive producer Jemima Khan was one of the people who put up bail money for him. So obviously she had contact with a lot of his advisors. And some of his lawyers I know reasonably well. So I always thought it was gonna work out, but Julian, I think, likes to be seen as the puppet-master who’s controlling everybody. He wanted to be sure I was on his side and the message would be properly controlled. And I got off on the wrong foot with Julian when I announced to him early on that I was making the film whether he cooperated or not. I’ve said that to a number of people; that’s what I told Spitzer at the start of that film. But we had a weird six-hour meeting and he started ranting about all his enemies, and then he said he wanted to be paid, and then said that the market rate for an exclusive interview with him was a million dollars.

Has this market rate been paid by anyone?

Not that I’m aware of. I mean, he got a lot of money for his autobiography, or at least the initial advance was handsome. But I said that I didn’t pay for interviews, so that was off the table. He was in the midst of writing a letter denouncing a TV documentary done by Channel 4. He had given them an interview, and he felt they had betrayed him by not portraying him in a positive light. It’s amazing – if you think about this stuff, he’s acting like a propagandist or a press agent or a CIA agent, right? It’s not about, “I give you my testimony and then you do what you want.” It’s, “If I give you my testimony, you have to tell my story the way I want it to be told.”

I have to laugh now, in retrospect. I think I’m the only person in the world who didn’t get an interview with Julian Assange. If you look at all the clips I use, he’s been interviewed a lot And I remember him talking to me about the “60 Minutes” interview. He said, “Oh, yes, we did good intel on ‘60 Minutes’ to determine just the right reporter that would be appropriate to interview me. We knew exactly what his political views were so the interview would be positive,” Julian the puppeteer. So anyway, I said I wouldn’t pay, and he said, “What if, instead, you get me intel on all the other interview subjects?” (Laughter.) He wanted me to spy for him. “You come back to me and tell me all the things these people have said, and maybe I’ll give you an interview.”

There was a point in the movie where I started thinking about Col. Kurtz from “Heart of Darkness.” Who starts out with benevolent intentions and turns into this megalomaniac.

Correct. And I think it’s the Guardian reporter James Ball who mentions what has now become my favorite phrase: “noble cause corruption.” Which is a police phrase for cops who plant dope on people that they can’t get any other way.

Right. That’s one theory about what went wrong in the O.J. investigation: “We have to frame this guy because he’s guilty.”

Right. He’s a bad guy, you might not get him by legitimate means, so there we go. We know it’s hardwired in Julian because that was his original moniker as a hacker: Mendax, the noble liar. If you’re a good guy, it’s OK to bend the rules. That became the issue for me. I tried to separate it from WikiLeaks, the publication. It was sort of like, let’s go through all of this and try to get an understanding of what happened. What we liked, what we shouldn’t like – because there’s a lot to admire in WikiLeaks. The very idea of it, the brass balls he had to go forward and do this. A lot to admire. But that shouldn’t give him a pass forever.

“We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks” opens in limited theatrical release this week, with more cities to follow. It will be available on-demand, beginning June 7, from cable, satellite and online providers.

Shares