This week has been a disquieting one for journalists concerned about protecting their sources. The revelation that the Justice Department had been spying on AP reporters' phone records, although it came as no surprise to those attuned to this government's attitude to First Amendment protections, reinforced the importance of enabling the unsurveilled free-flow of information.

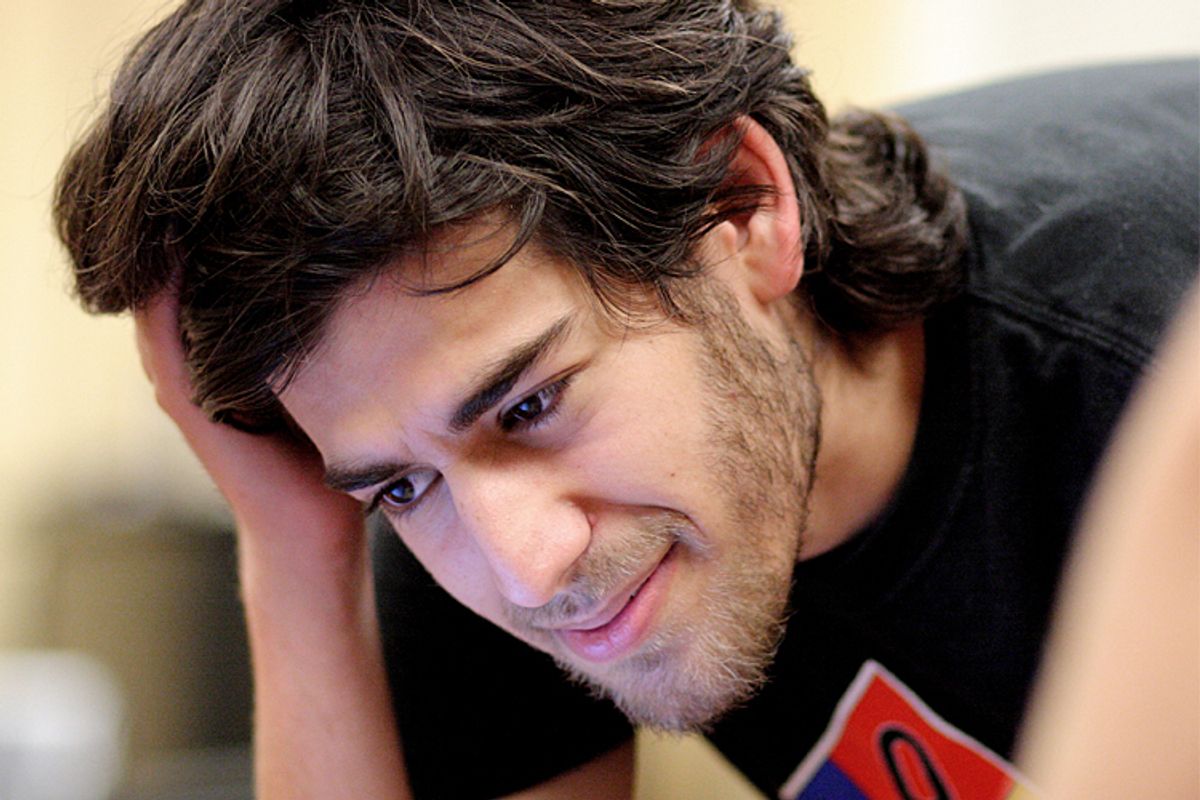

It was the right moment then, for the New Yorker to launch Strongbox, an open-source drop box for leaked documents, co-created by late technologist and open-data activist Aaron Swartz with Wired editor Kevin Poulsen.

"With the risks now so high – not just from the U.S. government but also the Chinese government that is hacking newsrooms in the West – it's crucial that news outlets find a secure route for sources to come to them," said Poulsen on Thursday.

The code, designed by Swartz and Poulsen, is called DeadDrop; Stongbox is the name of the New Yorker's program that uses it. The magazine announced that this means "people can send documents and messages to the magazine, and we, in turn, can offer them a reasonable amount of anonymity." Appropriate to the open-data activism to which Swartz dedicated many of his considerable talents, the DeadDrop code is open for any person or institution to use and develop.

DeadDrop lets users upload documents anonymously through the Tor network (which essentially scrambles IP addresses). With Stongbox, the leaked information is uploaded onto servers that will be kept separate from the New Yorker's main system. Leakers are then given a unique code name that allows New Yorker journalists to contact them through messages left on Strongbox. Like any system, it is not perfectly unbreakable, but it has already received high praise in reviews.

The Guardian's Ed Pilkington commented on the importance of DeadDrop in the context of the government's persecution of whistle-blowers and ever-expanding spy dragnet:

But this week's AP saga has also underscored the perils involved for anyone brave enough to try and leak information. As a further reminder of the dangers, Bradley Manning will go on trial next month facing possible life in military custody with no chance of parole for having been the source of the huge WikiLeaks trove of US state secrets.

The Manning trial has a further relevance to the launch of DeadDrop, Poulsen believes. In a pre-trial hearing in February, Manning disclosed that before making contact with WikiLeaks, he had attempted to hand his enormous mountain of digital documents to the Washington Post, New York Times and Politico, but failed to find a way into any of those organizations.

"This is the important lesson here. There was no natural route for Manning to gain entry, and it was a simple idea from WikiLeaks of creating a web forum where documents could be securely uploaded that led to their huge scoops."

There is, of course, a dark irony that the silver lining here is the launch of Aaron Swartz's open-source tool for the free flow of information in the face of government spying and persecution. After all, it was partly relying on his advocacy for open-data and shared information that government prosecutors targeted Swartz with hefty charges for downloading millions of online academic articles from JSTOR. The young technologist committed suicide facing a federal trial and potentially decades in prison. It has since been revealed that the government explicitly used his public open-data activism to build the case against him.

This week, the importance of Swartz's efforts and beliefs once again became manifest. The venerable New Yorker will be the first among many to rely on DeadDrop to protect sources and information to enable important stories to be made public. Swartz was not protected from the government overreach. But it is from such overreach that he is posthumously helping to protect the rest of us.

Shares