In May 2012, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Secretary of Treasury Timothy Geithner were poised to make a rare double visit to China for a high-level strategic and economic dialogue. The presence of both of these key cabinet officials at a delicate moment in the relationship between the two countries marked the importance of the issues. For once, economic interdependence and geopolitics were on the agenda at the same moment.

But on April 22, in the tiny village of Dongshigu in the eastern Shandong province, something happened that would eclipse the visit. Chen Guangcheng, a blind dissident lawyer-activist, managed to scale a high wall to escape the building where he had been under house arrest for two years. Chen broke his foot in the process, yet over the next several days, with the help of other activists, he managed to make his way four hundred miles to Beijing, where he was taken into the U.S. embassy. On April 27, when he was inside the embassy, a YouTube video was posted in which Chen informed Premier Wen Jiabao that he had escaped and demanding punishment for the local officials who had detained him.

In the days that followed, Chen’s future became an international incident of the highest order. Chen first insisted he did not want to leave China. Then, after he was transferred to a Chinese hospital to have his foot treated, he changed his mind. In an emblematic piece of cool war theater, Chen, from his hospital bed, used a borrowed mobile phone to address an open hearing of the U.S. Congress in Washington. He told the congressmen — and the world — that he was worried for his family’s safety and wanted to come to the United States.

Chen’s predicament, featured for days on the front pages of the U.S. press, drew Western eyes away from the secretarial visit. Finally, after days of intense negotiations between ranking U.S. diplomats and their Chinese counterparts, Chen obtained permission to travel to the United States as a special student, a “solution” that spared China the embarrassment of having Chen granted asylum status. The pressing questions of politics and economics that were supposed to be the subject of the visit were ignored, replaced by the subject of human rights.

The Chen Guangcheng episode hints at the hugely complicated and hugely important way that human rights will figure in the cool war. The United States showed a willingness to put human rights issues front and center, even when other issues were supposed to be on the table. The upstaging of a major diplomatic encounter by a focus on China’s human rights violations may conceivably have been planned by someone within the U.S. government, since the whole story of Chen’s escape seems highly improbable without help. Even if the timing of Chen’s escape was accidental, the U.S. embassy still had to decide to take Chen in, creating an inevitable crisis. Either way, the United States knowingly put human rights first in a highly public forum.

From the Chinese standpoint, the whole episode must have been frustrating and embarrassing. Enormous diplomatic resources went into discussing the fate of one previously little-known human rights activist. Instead of being treated respectfully as a rising global power, China was being scolded as a rights violator. The United States seemed to be using human rights to weaken China and give itself an edge in discussions between them.

The emerging historical moment is creating a new context for the rhetoric and practice of human rights. For the first time since the fall of the Soviet Union, the United States now has a major incentive to promote the international human rights agenda. So long as China continues to violate human rights, there may be no better ideological tool for the United States to gain advantage under cool war circumstances.

To understand the trajectory of how human rights will matter and be used in the coming era — and to predict how China will respond — we need to turn back to the origins of our ideas and practices of human rights. The combination of sincere belief and cynical manipulation in the human rights realm goes back to the end of World War II and the Cold War, and it demonstrates how power politics will necessarily shape the development of human rights in the future.

Cold Rights

Since the Nuremburg tribunals, it has been accepted in principle that the world should try to bring to justice the worst violators of international humanitarian law, which applies in wartime. The Nazi trials were not all they are sometimes remembered to be, and many contemporary observers believed they were little more than victors’ justice. Nevertheless, they did create an important new precedent. For the first time, members of a government were held criminally responsible by an international body for harms to individuals that they committed while in power. In this sense, at least, universal human rights were demonstrated, declared, and acted upon.

Then, from a practical standpoint, nothing much happened.

Early in the Cold War, the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. That document, however, was not law. It was not even international law. It was called a declaration because it was, in legal terms, a hopeful, aspirational statement of ideals, but it had no enforcement mechanism and no legal commitment by the signatories to follow it.

For most of the next twenty-five years, the topic of human rights rarely figured in American political rhetoric at the international level. It is not hard to see why. Until 1954 the United States had a formal, legal system of government-mandated segregation in place in many of its states. Until 1964 no federal law expressly prohibited racial discrimination by businesses. The next decade was spent in the painful process of trying to negotiate racial integration, not only in the American South, but in Northern states where segregation operated on a de facto basis even though it had not been enshrined in law. During these years, the United States had a great interest in avoiding public discussions of human rights. The Soviet Union, for its part, was able to point to race discrimination as evidence of U.S. hypocrisy.

In the middle of the 1970s, things began to change. Having greatly reduced its vulnerability to the charge of institutional racism, the United States could use the ideology of human rights to attack the Soviet Union. The presidential administration of Jimmy Carter began to institutionalize human rights criticism. Congress mandated annual country reports to monitor human rights violations around the world, including among U.S. allies. This was recognized at the time as something new, even humorous. Cartoonist and political commentator Garry Trudeau created a new Doonesbury character — a pleasant, ineffectual human rights officer in the Carter State Department — and had him present various absurd awards for human rights “compliance.” The effect of these cartoons was not primarily to accuse the U.S. government of hypocrisy, but to note rather sweetly the irony that this Cold War power was beginning to speak the language of rights instead of power.

At the same time, Eastern European dissidents, at great personal risk, signed documents like Charter 77 that condemned the Soviet system for violating human rights, to which it had made a symbolic commitment in the 1975 Helsinki Accords. This was a new strategy, a product of the Brezhnev era. The dissidents were making a play for Western attention and the support of Western governments — and they got it. The human rights movement as a distinct, popular social movement swung into gear.

The movement to free Soviet Jewry marks a striking example of Cold War human rights ideology. The movement primarily consisted of Jews in one country seeking the rights of Jews in another country to practice Judaism and to emigrate to Israel. But it presented itself as a claim for the universal human rights to the freedom of conscience and travel. Its target was the Soviet Union. Initially foreign policy realists like Kissinger dismissed the movement; seeking détente, he told President Richard Nixon in no uncertain terms that the United States had no national interest in helping Soviet Jewry, even if they were to be gassed. Eventually, however, the movement managed to ally itself with Cold War strategy. Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson successfully introduced legislation linking aid to the Soviet Union with the freeing of Soviet Jewish dissidents.

When the Cold War ended, the situation for human rights changed again. For the first time since Nuremberg, where the Americans and the Soviets had cooperated in the aftermath of their World War II alliance, new international tribunals were created to punish terrible wrongs. The international criminal tribunals for Yugoslavia and Rwanda, established in the 1990s, could not have happened during the Cold War, not because there were no massive human rights violations or even genocides during that period, but because every rights violator and genocidal dictator was in the pocket of either the United States or the Soviet Union. With the Soviets no longer on the scene, the United States and Western Europe could use criminal tribunals to make some after-the-fact reparation for their failure to prevent horrible post–Cold War crimes.

As the tribunals were gathering steam, the Western European powers, with guarded U.S. participation, drafted the Rome Treaty, got signatories from around the world, and created the International Criminal Court. This permanent body is supposed to provide a regularized forum for doing the work performed by the special criminal tribunals erected after genocides. The ICC, too, would have been inconceivable during the Cold War, when both superpowers would have worried that such an entity might indict their dictator clients, to their own political detriment.

When the United States invaded Afghanistan and Iraq, its perceived interests regarding international rights enforcement shifted once more. The Clinton administration had signed the Rome Treaty creating the ICC. Under George W. Bush, the United States officially withdrew its signature. In the post-9/11 era, with two wars to fight, Americans worried that their soldiers — or even their civilian leaders — might find themselves charged with war crimes before the ICC.

Beneath the immediate concern with the risks of violating international humanitarian law while war fighting lay a deeper structural reason for the United States to worry about international law. As the dominant global power after the Soviet collapse, the United States could do more or less what it wanted internationally. International law was therefore likely to be used to criticize the United States. Under these circumstances, strengthening the human rights regime more generally might carry appreciable costs to American freedom of action. Giving voice to this view, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld called international law “a tool of the weak.” Scholars complained about “lawfare,” the use of human rights law to achieve political or military aims. According to this vision, hampering U.S. freedom to act amounted to abuse of the pure aims of human rights.

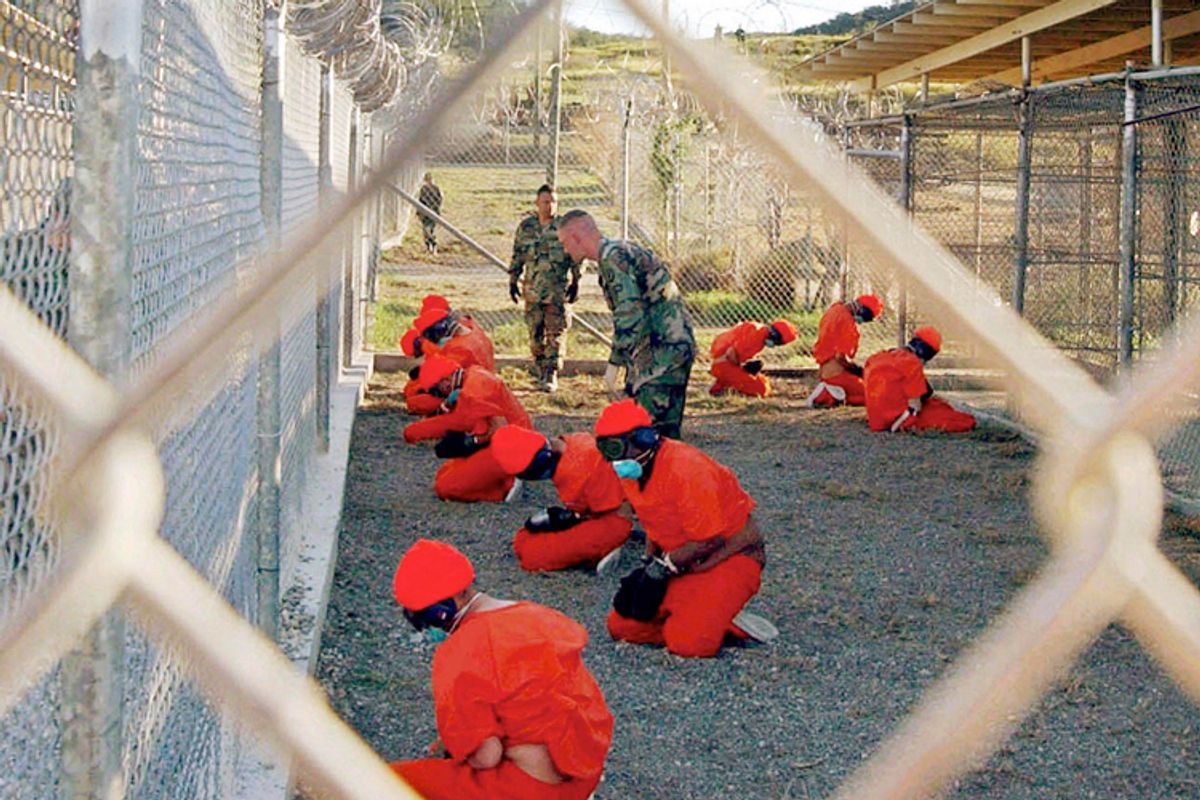

To be sure, during this period of war in Afghanistan and Iraq, the overall U.S. position was ambivalence about international law and human rights, not total rejection. In fact, the U.S. government became much more concerned about complying with the laws of war than it had ever been before. Although the executive branch violated international law in Guantánamo, the U.S. Supreme Court, another branch of the government, held that international law had to be applied there, at least insofar as it was incorporated into U.S. domestic law. The Court required hearings for detainees and then struck down the special tribunals that the Bush administration created. International law played a role both times.

Even under George W. Bush, then, the U.S. government never wholly turned its back on the international rights regime — because human rights law still served U.S. interests. Most of the time, under most circumstances, the United States respects human rights much more than most nondemocracies. That respect makes it more legitimate as an international actor, the same way violations make it look illegitimate. For the United States to abandon human rights altogether would take away an important source of international legitimacy. It would provide a long-term advantage to countries that systematically violated or ignored human rights.

The U.S. government, then, has always used the ideology of human rights as a political tool, deployed when convenient and ignored otherwise. It allied itself with human rights violators during the Cold War; during the war on terror, it justified its own human rights violations by the necessity of protecting the security of the liberal democratic state. Today, now that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have wound down and China has continued to rise, the U.S. interest in focusing on human rights looks much stronger.

The Chen incident showed how far the United States is willing to go, imposing embarrassment and humiliation on China without much concern for the costs to the relationship between the countries. When the United States aligns itself with the international human rights movement in criticizing China, the rights movement will gladly accept its assistance, because China is a far greater rights violator — and because China has not yet accepted the Western universalist conception of human rights that the movement mostly advocates.

Can China Change?

Could all that change? Could China gradually become a human-rights-respecting country, even without becoming a democracy? In the short run, the answer is no. From the Chinese standpoint, the international human rights agenda poses serious dangers, and China can be expected to oppose it. Today, looking at the collapse of the Soviet Union as a negative model, the party believes that lifting its control over speech and protest and many other aspects of Chinese society would likely bring an end to its rule. The party’s overarching interest — remaining in power —precludes rapid advances in human rights.

This perspective will also in the near term be expressed in China’s international attitude toward other rights violators, who are potential allies. With its increased power, China has increased capacity to block human-rights-related initiatives. Thus, for example, one can safely predict that China would not allow any more ad hoc international tribunals to punish genocidal leaders. The ICC will, for the time being, proceed very slowly and cautiously, concerned not only about the nonassent of the United States but about opposition from China as well.

But this pessimistic vision for the short term is not necessarily stable. In the longer run, China’s respect for human rights could evolve — and cool war conditions may encourage that evolution. Begin with the fact that China’s stance on human rights is already different from where it was in the early post–Cold War period. In the 1990s, Chinese leaders seemed sympathetic to what Lee Kuan Yew, then prime minister of Singapore, famously called “Asian values,” intended as an alternative to what he considered the Western ideals of human rights and democracy. According to this notion, some Western principles of human rights, such as free speech and the value of individual autonomy, were flatly incompatible with “Asian” governance. Lee’s argument pitted Western individualism against Asian collectivism. In place of democracy and autonomy, he offered a soft authoritarian regime based on Confucian paternalism.

In contrast, China today typically does not deny that human rights are real or universal. Chinese elites invoke Asian values (or sometimes Confucian values) primarily to justify a development path that ultimately leads toward individualism. Chinese-style Asian values may pass through paternalism as an intermediate stage along the way to individual rights and freedoms. But the end goal is no longer always described in terms so starkly different from the end goals of liberal, rights-respecting democracy. Few of those elites now claim that Chinese values are inevitably collectivist or anti-individualistic.

Instead, when challenged about human rights violations, China’s leaders have offered a characteristically pragmatic answer. According to the Chinese government, human rights must be defined so that they include not only negative rights against mistreatment by the government but also positive rights to economic well-being. China’s path of party-led economic development, they say, is necessary to create the conditions through which the human rights to health and well-being can be assured. Limitations on the right to free speech or the right of conscience are seen as necessary at this stage and under these conditions.

In essence, the Chinese are saying that granting individual rights of the kind found in Western democracies might well bring down their system. The system is justified by the fact that it is facilitating rapid economic growth. Therefore, they conclude, China is not violating human rights when it arrests dissidents and suppresses public protest. It is actually doing what it can to realize other, equally important human rights.

This argument may sound preposterous to Western ears, but it is worth considering. The claim that human rights include the right to live decently and well, a right that can only be brought about in a country with a certain degree of economic development, is one that some Westerners might accept. Imagine an impoverished person living in a big city in India without access to housing, sewage, education, or adequate nutrition. He may have the right to free speech and free exercise of religion. He may even have the right to vote. But surely this is not sufficient for someone whose life prospects are so extraordinarily limited by circumstance.

Confronting this problem, some philosophers have argued that human rights should be defined by humans’ equal capabilities to live out the lives they choose for themselves. Living in a place where there is a certain basic level of economic development is a precondition for being able to exercise other capabilities. According to this view, economic development is a human right itself, indeed an important basis for many other human rights.

To be sure, the Chinese government has not fully adopted this capabilities-centered approach to human rights. But apologists for the Chinese system are, knowingly or not, offering a variant on it. They are claiming that freedom from government interference is meaningful only once the society is rich enough that people can do something with the rights they have.

Supporters of human rights should not assume that this gradualist argument is intended hypocritically. Many elites in the Communist Party believe sincerely that the system of government they are pragmatically developing offers the best possible solution to the improvement of the lives of people in China. It is obviously self-serving for them to believe that staying in power is necessary for delivering true human rights. But almost all elites everywhere in the world believe that their own influence and power serves the common good — and sometimes they are right.

What all this means is that unlike traditional Chinese communism, with its ideological commitment to reeducation and the creation of a new kind of human being and a new kind of society, China’s pragmatic governance today has no principled reason to oppose individual human rights. Indeed, individualism is on the rise in China as a result of party policies promoting entrepreneurship and consumption.

Consumers’ Rights

The party’s planners want to create a domestic Chinese market capable of buying Chinese goods: In short, they aim to generate a nation of consumers. This kind of consumption in turn requires a culture of individualism in which citizens buy things for themselves instead of just saving for their families and their future. China’s emergent cultural individualism will create local demand for greater freedom.

Consumerism, for better or worse, is intimately connected to modern ideas of human rights. Human rights free individuals to pursue life plans in which they experience themselves as making choices. Choices of religion, of belief, and of government fit this description. The right to be treated equally is also necessary to feeling free, and making at least some basic free choices is a minimal condition for dignity.

Citizens who are making free choices in the market will likely want governments to maximize the choices available to them as individuals — and vice versa. Those choices include important life decisions. But they also include the more trivial decisions of everyday existence, decisions that are often expressed in earning a living and buying things with one’s money. Production and consumption are important areas for free choice in Western society. It is no coincidence, therefore, that ideas and practices of human rights have arisen in places where economic choice is also relatively unfettered.

While China could develop a culture of consumerism without developing a major demand for human rights, it is far more likely that the gradual increase in consumerism will go hand in hand with greater demand for rights. In general, the two proceed in tandem. Even relatively poor India is strikingly consumerist, in part because of its postcolonial tradition of respecting human rights. Russia developed consumerism at the same time as it was extending individual rights, and although it has since scaled back rights, it has seen no reduction in consumerism. Saudi Arabia, one of a handful of exceptions, has a growing consumer culture without respect for basic individual liberties; yet today there are no examples of countries that have human rights and do not have a consumer culture.

Faced with a gradually increasing demand for rights, the party would increasingly have reason to respect them if it could do so without ceding its governing position. Externally, the benefits of extending human rights within China are real. Respecting rights would make it harder for the West to criticize China. It would remove one of the key American arguments to China’s neighbors about why they should fear rising Chinese influence in their region. Internally, responding to a desire for rights could strengthen the party’s legitimacy. The all-important question is whether these benefits of increasing respect for rights would outweigh the danger that the party would be weakening its grip on power by loosening its control over Chinese society.

To imagine the possibility of rights-respecting party rule, we need to unsettle our assumption that only democracies respect human rights. Seen historically, authoritarian government and individual liberties have sometimes coexisted. European states, for example, gradually extended rights for a century or more before they adopted democracy.

Over time the party could strengthen the rule of law, move away from arbitrary arrest, expand freedom of religion, and allow more free speech while still maintaining its dominant position and punishing any revolutionary attempt to challenge its power. This vision could follow from the ways the party is now trying to develop a system of governance that solves the problems of democracy without resorting to elections. If the party’s legitimacy can be preserved through responsiveness, accountability, and meritocracy while economic growth proceeds, people might not use their rights to try to undercut the government and establish democracy.

Law to the Rescue?

The possibility that in the long term China may increasingly respect human rights raises a further question for the world more generally: Can we imagine international law actually beginning to enforce human rights? At present, the leading human rights treaties provide no provisions for their own enforcement. If a country is found to have violated the rights contained in the treaties, the only cost it suffers is to be deemed outside the community of nations. And if there is one emotion that serial human rights violators tend to lack, it is a sense of shame.

Without ascending into utopianism, it is possible to identify some possible new cool war avenues for the international rights agenda. The key is for advocates to find ways to link rights to economic interests. Today the element of international law that is most consistently enforced is economic law, particularly the law of trade. Where violations of human rights are also violations of international economic agreements, the developing rule of international law could come to affect human rights.

Suppose a country allows local firms to use slave labor. A foreign country could argue before the WTO that this human rights violation is an unfair subsidy of the products being made by slave labor. Or consider a country that tortures its citizens in order to extract oil from some region of the country where the local residents want a larger share of the value created by the oil. Foreign states could claim that the oppression is artificially lowering the costs of oil exports, thereby discriminating against other oil manufacturers.

The exact nature of the claims would vary from case to case. In practice, they would probably be brought to the attention of Western governments by coalitions of human rights activists and corporations whose competitors were benefiting from the abuses, in the way Google tried to challenge China’s speech regulations. The strategic goal would be simple: The WTO carries the promise of actual, binding enforcement that nations obey. For the first time, it might be possible to press Western governments to challenge other countries on human rights violations in a venue where a legal victory would have concrete results. If this actually happened, international human rights would look more like law and less like a set of idealistic aspirations.

As always, the real game for human rights advocates is getting friendly governments to exert pressure on the worst violators. For this approach to work, the United States, for example, would have to believe that the benefits of lodging a complaint outweigh its potential costs. The U.S. government has an interest in leveling the playing field for U.S. companies doing business in China. Simultaneously, the United States has an interest in condemning human rights violations in China, both for reasons of principle and in order to gain advantage in the race for allies.

Turning the WTO into a forum where human rights claims could be heard, albeit obliquely, would run the risk of China withdrawing from the treaty. A credible Chinese threat to that effect would likely sink any chance of the WTO regime extending to human rights. But if and when China gradually improves domestic human rights conditions, the benefits it reaps from the WTO may make China more likely to stay and fight than exit the trade regime.

Far less costly would be to argue before a WTO tribunal that the specific practices being criticized have nothing to do with trade discrimination. So long as China adopted this strategy, it could actually become possible for other states to bring trade-linked human rights claims before WTO tribunals.

The deeper point here is that the central positive lesson of the cool war — that economic interdependence can be leveraged to help manage real political conflict — has value for human rights. As we have seen, international law can function and be enforced without a supersovereign so long as the economic interests of the main participants lead them to remain inside the system, even when they lose cases and must pay damages. Indeed, this can occur even when the players, like the United States and China, remain competitors in the arena of global power.

That enforceable international law can coexist with a fundamental struggle among great powers opens the possibility for gradual expansion of the realms in which law operates. The example of human rights suggests that the conditions of cool war need not drive us to despair. To the contrary, there is room for improvement even in the dangerous and complex world in which we now live.

Excerpted from "Cool War: The Future of Global Competition" by Noah Feldman. Copyright © 2013 by Noah Feldman. Reprinted with permission by Random House, New York, NY.

Shares