Muhammad al-Baidhani, an 11-year-old Yemeni boy with a mop of brown curls, only knows his father from photos and a one-hour video conference every two months. Before Muhammad was born, his father was captured and sent to the U.S. military prison at Guantánamo Bay, where he’s been held without charge ever since.

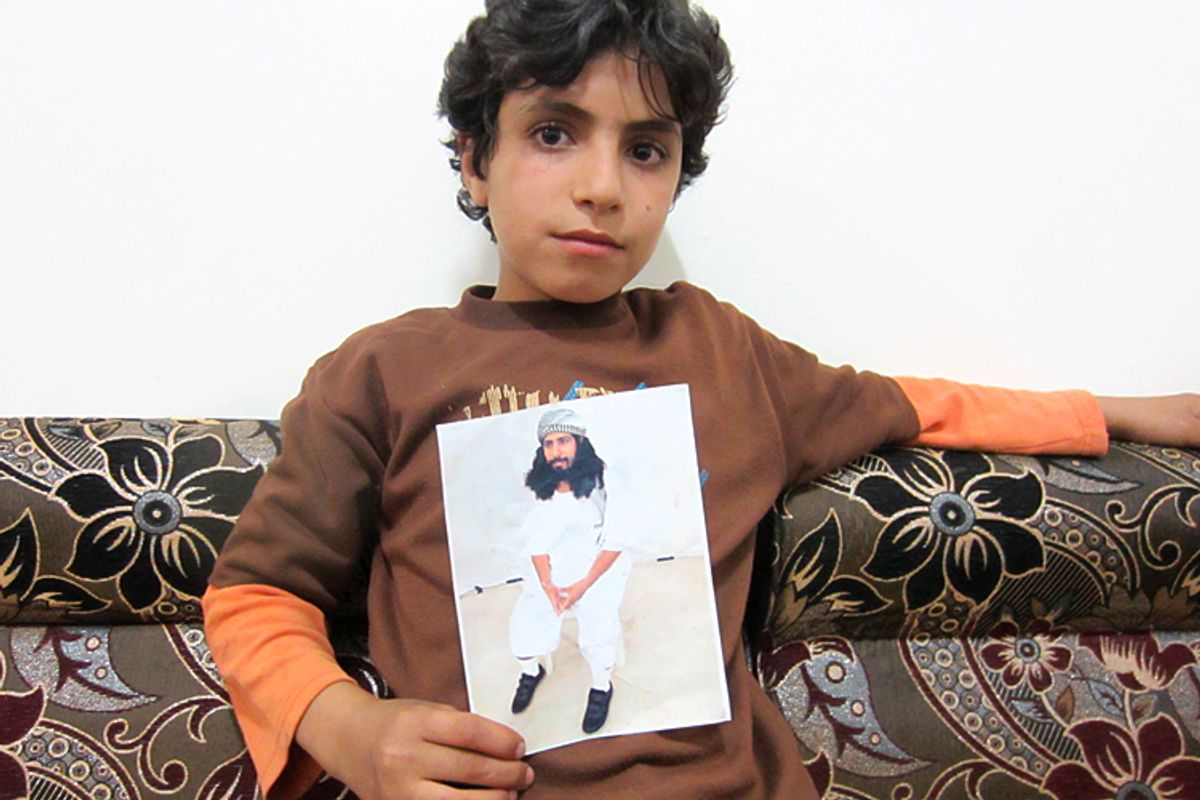

“Thanks to the U.S., I don’t even know what the word ‘Dad’ means,” Muhammad told me when we met at his family’s house earlier this month in Sanaa, the Yemeni capital. Clutching a portrait of his father, Abdul Khaliq al-Baidhani, in a white prison jumpsuit, he added: “I just want the U.S. to send my father home.”

If President Obama stands by his statements on Thursday, Muhammad may finally get his wish. During a wide-ranging speech on counterterrorism policy, Obama vowed to lift a freeze on repatriations of Yemenis from Guantánamo that he imposed in January 2010, days after a botched effort to attack a U.S. airliner that authorities linked to Yemen. Obama also renewed the pledge he made on his first day in office in 2009 to close Guantánamo altogether – though without offering a time frame.

But when I contacted Baidhani’s relatives for a response to Obama’s speech, they sounded almost as bleak as they had when I met them in Yemen. They noted Baidhani had been cleared for transfer from Guantánamo as far back as 2006 and again in 2009, meaning the U.S. had no intention of prosecuting him and did not consider him a serious threat to the U.S.

“I hope this is Obama’s last speech on this topic and that he means it this time,” said Baidhani’s mother, Um Abdul Khaliq. “When we learned a few years ago that my son was cleared to come home, we were dizzy with joy, but as the years passed we lost faith in America.”

That pessimism is echoed by other detainees’ families and also by many in the broader Yemeni population. At the start of Obama’s presidency, many Yemenis appeared to support U.S. counterterrorism measures in their Arabian nation, home to al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula, which Washington views as a top security threat. But then the U.S. began a targeted killing program in Yemen, using drones and manned aircraft to carry out more than 50 estimated strikes on alleged terrorist targets.

Groups that track targeted killings through media reports contend that the attacks have killed hundreds of people, including dozens of civilians. The U.S. refuses to confirm numbers while insisting, as Obama did again in his speech, that civilian death rates are far lower than the media report. Yet I recently verified 12 civilian deaths in one single strike outside the central Yemeni city of Radaa in September 2012. The U.S. has neither apologized nor compensated the victims’ families, let alone announced any investigations. While Obama said on Thursday that he was “haunted” by civilian deaths and that the U.S. would take extra care during targeting, he offered no admission of a U.S. role in unlawful attacks.

Meanwhile, back at Guantánamo, more than 90 Yemenis remain behind bars — the largest bloc by nationality among the 166 prisoners. Many Yemenis have joined a prison hunger strike to protest their detention without charge for nearly 12 years. Indeed, the only Yemeni to come home from Guantánamo in recent years was Adnan Latif, who returned in a body bag, prompting an outcry in Yemen. Latif, who had repeatedly tried to kill himself at Guantánamo, had, like Baidhani, been cleared for transfer since 2006. He was found dead in his cell last September from an apparent overdose of his medications.

Left untended, this combination of detention of Yemenis without charge at Guantánamo and civilian killings without accountability in Yemen threatens to torpedo the Yemeni-U.S. counterterrorism relationship, and at a critical moment. After a long, rocky rapport with Yemen’s former leader Ali Abdullah Saleh, Washington views the country’s new president, Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi, as a staunch counterterrorism ally who is serious about thwarting future attempts to attack the U.S.

Baidhani, now 30, left for Pakistan during his wife’s second pregnancy to find work to support the family. A classified U.S. government document released in 2011 by WikiLeaks said he met an alleged militant in Karachi who persuaded him to train at a Qaeda military camp in Afghanistan during the summer of 2001. Baidani was captured trying to flee Afghanistan after the U.S. invaded that country in October 2001. Yet he was never charged and his trip to Afghanistan does not make him a threat on its own: Yemeni youths routinely traveled to Afghanistan for military training before 9/11 with the blessing of their government and without any intention of harming the U.S.

In addition to Muhammad, Baidhani has a 14-year-old daughter, Faina, who was just a toddler when he left for Pakistan. “When the children speak with their father during the video conferences, they all break down crying,” Um Abdul Khaliq told me.

Obama can still salvage the goodwill of the Yemenis, but only if he swiftly acts on his vows to close Guantánamo and curb civilian losses in targeted killings. But continued delays and deaths will only harden more Yemeni hearts, which can’t make for a strong counterterrorism policy.

Shares