Crime and punishment: Dostoyevsky was far from the only writer to recognize how much a society reveals about itself in the way it handles both. For novelists, a detective can serve as a roving eye, licensed to peer into the secrets of every social stratum, while a trial, with its pitched adversaries and high stakes, becomes a dramatic way to decide not only what happened but who, if anyone, is to blame.

That’s how Paul Collins uses the famous real-life murder mystery at the center of “Duel With the Devil.” This sensational crime took place in Manhattan in December, 1799, on the very brink of a new century (or not quite, if you’re the sort of pedant who insists that the millennium didn’t really turn until New Year’s 1801 — and yes, those people were around back then, too!). The body of a young Quaker woman, Elma Sands, was found at the bottom of a well in Lispenard Meadows, a swath of marshy, undeveloped land that separated New York City proper from Greenwich Village, approximately where the neighborhood of Soho stands today. The guy almost everyone liked for the killer was Levi Weeks, a carpenter who lived in the same boarding house as Sands, an establishment run by Sands’ cousin, Catharine Ring, and her husband, Elias.

Weeks had given every indication of courting Sands, and Catharine Ring testified that the night Sands disappeared she had said that she and Weeks planned to marry. Ring furthermore maintained that she’d heard someone leave the boarding house with Levi Weeks that night. Rumors of these and other bits of evidence against Weeks (some of it fabricated) flowed through the city at remarkable speed, almost as if someone were deliberately spreading it. Even without cable news or Nancy Grace, the public quickly leapt to the conclusion that Weeks was the culprit, and it began to bay for his head.

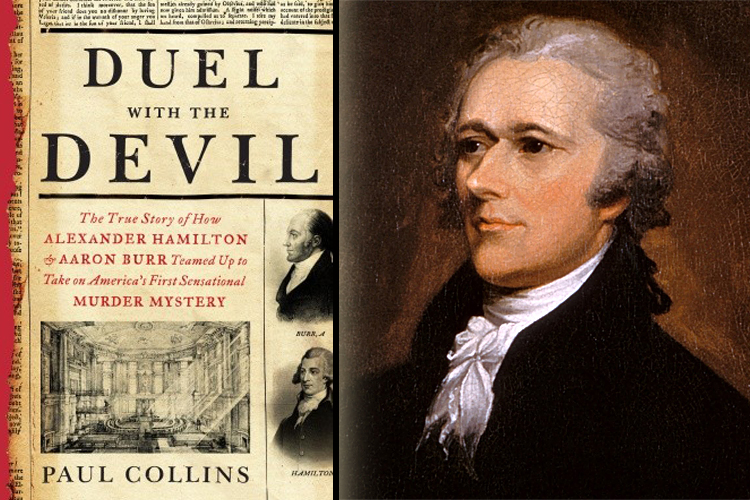

Weeks worked for his brother, Ezra, who happened to be one of the town’s most prominent building contractors, and whose house Levi was visiting during the night of the murder. Ezra hired a threesome that Collins calls “the best lawyers in Manhattan” to defend his brother: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr and Henry Brockholst Livingston. This made for “the greatest criminal defense team New York had ever seen,” even if two of of the attorneys were political adversaries. Hamilton and Burr were “the worst of friends — or, perhaps, the best of enemies,” as Collins puts it, Revolutionary War heroes and founding fathers who still sometimes dined together with their families but who plotted each other’s political downfall. Four years later, Burr would shoot Hamilton dead in New Jersey, and spend many long years afterwards living it down.

The Manhattan Well mystery is part of New York lore, as well as the occasion of a legal milestone: It was the first murder trial to have its proceedings fully transcribed, thanks to the popularization of shorthand. The transcript itself was published as a book by the court clerk, William Coleman, who later went on to become the first editor of the New York Post, a newspaper founded by Hamilton. Hamilton was the first secretary of the treasury and established the Bank of the United States. Burr was a former senator and would go on to become Thomas Jefferson’s vice president. “Duel with the Devil” is littered with names that even the most historically-illiterate New Yorker will recognize because those names were given to streets, neighborhoods and subway stations. The cast of this drama is illustrious to a fault.

But that’s not how Collins plays it. “Duel with the Devil” is the story of a small town, a place where everyone knew everyone else and the fix was always in. Lively, immediate and dishy in the style of a top-notch tabloid columnist, he has distilled what must have been months of primary-source research into a slender volume that fizzes with the energy and irreverence of an infant republic. Collins tells you what the street signs said (“Antoine Arneux, A la Paris, Marchand Tallier … Shopkeepers mentioned their hometowns in the hope of landing customers from their newly arrived countrymen”); what libations tavern drinkers favored (“cherry bounce, a sweet dram of cherry brandy spiked with extra sugar” or “blackstrap, a witches’ brew of rum, molasses and herbs”); what entertainments people sought out on their days off (an exhibit boasting a “Mongooz, a beautiful animal from the Island of Madagascar”); and what the auctioneer across the road was crying out (“Port wine! Cognac! Capers and olives! Herring and shad!) when Weeks arrived at Bridewell prison to be locked up pending his trial.

In addition to all this color, Collins provides a saucy breakdown of the twisty and interlocking interests behind Weeks’ case. Both Burr and Hamilton (who never billed for their legal services in this trial) were beholden to Levi’s brother Ezra for assorted construction projects, past, present and future. The disused well where Sands’ corpse was discovered belonged to Burr’s Manhattan Company, a complicated venture ostensibly created to pipe fresh water into the city (which it did), but in actuality a Trojan horse used to set up an alternative to Hamilton’s monopolistic Bank of New York. One of Burr’s most ingenious gambits, the Manhattan Company helped break the political stranglehold with which Hamilton’s Federalist Party controlled the city, and thereby made the election of a Republican president, Thomas Jefferson (not to mention his Republican vice president, Burr), possible. The outfit later became Chase Manhattan bank.

This is New York politics in all its gritty glory — which is to say not much in the way of glory at all. While sober-minded and reverential accounts of the founding fathers’ lives have their place, it helps to be reminded now and then that these fellows weren’t saints and that the early days of the U.S. were as rife with partisan rancor and shady shenanigans as our own. A surprising number of the luminaries who appear in “Duel with the Devil” were beaten up in the streets at one point or another by someone they’d offended, and Collins depicts an episode in which Burr used his ruthless legal expertise to intimidate a legitimately aggrieved creditor. And as for the personal life of the secretary of the treasury, well: “Nobody needed to ask why Martha Washington had nicknamed her tomcat Hamilton.”

The trial itself provides a window on the legal procedures of the time. They were very keen on jury sequestration (the jurors had to sleep on the floor in the portrait room of the courthouse) and not so finicky about conflicts of interest. Collins writes, “Burr’s company owned the murder scene, had employed the defendant, had rejected a bid by a relative of the deceased, and had financial relationships with the court recorder and the clerk, and political alliances and rivalries with his fellow counselors, the mayor and the judge.” The prosecution’s chief medical experts had only examined the body after it had been dragged out onto the streets by Sands’ family in attempt to drum up public outrage. The court’s officers balked when it seemed that the trial might extend to the unprecedented length of three days.

As for the crime itself, Collins has his suspect, although a blurb that boasts “the first substantial break in the case in over 200 years,” is probably overstating things. I will not spoil it. Lispenard Meadow is long gone, but to this day, if you drop by the (reportedly dreadful) Manhattan Bistro on Spring Street and ask to be let into the basement, you can still see the over-200-year-old Manhattan Well where Elma Sands died. However much the surface of the city may change, the deep-down stuff remains the same.