Written, produced and directed by Tom Bean and Luke Poling, Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself opened in New York on May 22, 2013; it will open in Los Angeles on June 7.

Written, produced and directed by Tom Bean and Luke Poling, Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself opened in New York on May 22, 2013; it will open in Los Angeles on June 7.

SOMETHING SPECIAL was brewing in the East Coast literary world after World War II. Long before, in A Hazard of New Fortunes (1890), William Dean Howells had documented the shift of national culture from Boston to New York. The intervening 60 or so years had seen another major shift. As the model of the movie star became the decisive influence in literature as in so many fields, a lot more bells and whistles were added to the idea of the American writer. It wasn’t enough any longer merely to achieve; you had to be seen to achieve. Whether it was the ostentatious physical risks of Hemingway the bullfighter and white hunter, or the guttered candle of Fitzgerald in Hollywood, this new American writer not only had to write, but to be, preferably in a flamboyant, self-dramatizing configuration of talent and nerve. The degree of failure or success was somewhat less important than making an unforgettable impression. As Jack Kerouac wrote, “The only people for me are the mad ones […] [who] burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars” — and he was not alone.

In an era when Life magazine anointed Jackson Pollack as the great American artist and Hemingway as the great American writer, the young men (especially) who came out of the war — Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal, James Jones, and so many more — all wanted to make their own marks on this newly enhanced world of fame and celebrity. And in no place was the competition more intense, the arena so significant, than in New York City. Lorenz Hart’s Manhattan was “an isle of joy,” Comden and Green’s “a helluva town.” But the postwar atmosphere was more succinctly captured a decade or so later by Kander and Ebb: “If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere.” It was the world that J. D. Salinger, for one, longed to be part of, and then beat a hasty retreat from, when it arrived in the form of rabid fans on his doorstep.

The total mobilization of World War II had also ignited the quest for the Great American novel, and the flyleaf biographies on new fiction often listed a writers’ bona fides — a working stiff’s sampler of the American scene: fire spotter in Idaho, lobster fisherman in Maine, short order cook in Mississippi, valet car parker in Los Angeles. (Today, it would probably list what writing programs gave him or her an MFA.)

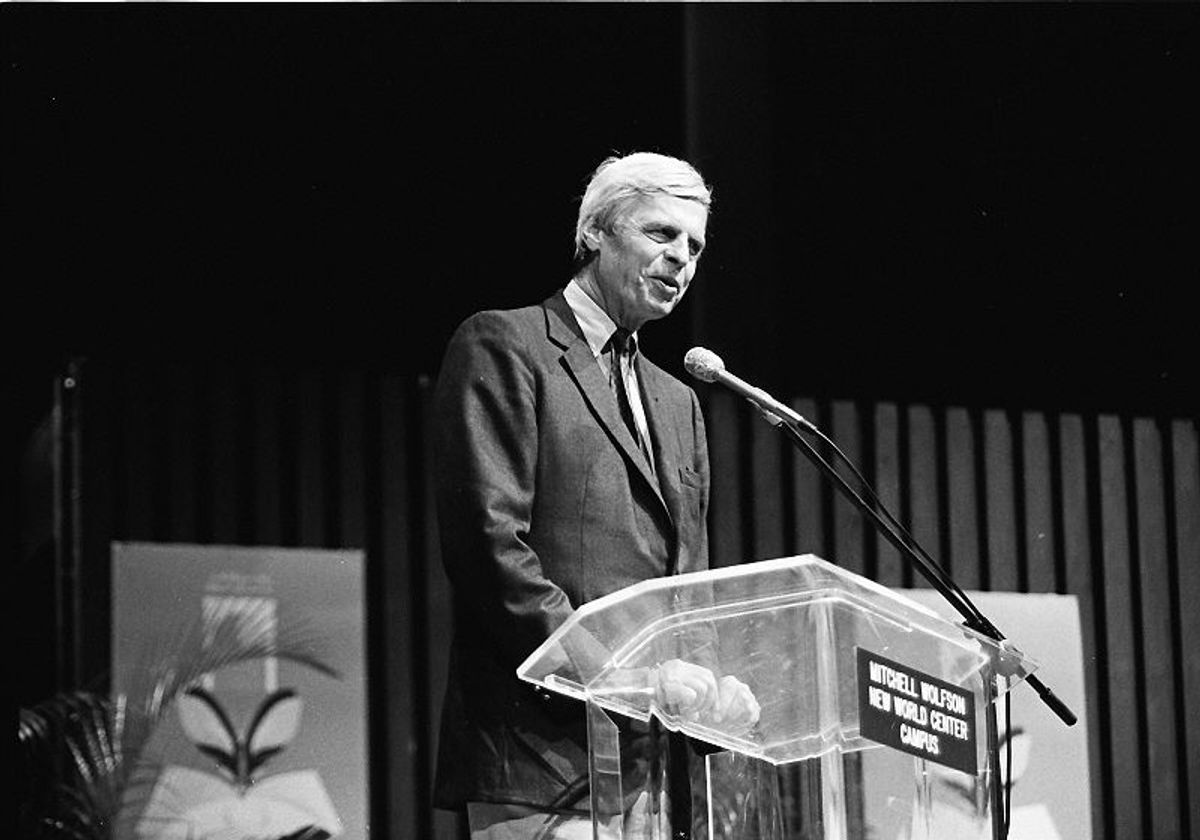

Into this world that valued youth and rough experience came a patrician New England WASP named George Plimpton, who became the first editor of The Paris Review in 1953 and a dabbler in virtually everything — or at least everything with an audience. The new documentary Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself tries and to a certain extent succeeds in capturing something of his unique place in the mix, his achievements, and the tantalizing blend of highbrow and populist in his nature. It’s an intriguing and emblematic story.

Beside his 50-year shepherding of The Paris Review, with its outstanding record in publishing new fiction and its interviews with often elusive and reclusive writers, Plimpton was famous in his day for a series of books, articles, and television shows that recounted his adventures as an amateur trespassing in the worlds of professionals. As television was bringing sports and a smattering of culture into everyone’s living room with an unprecedented immediacy, Plimpton cast himself as the everyman of public experience. His professed goal was to climb down from journalistic detachment and actually participate in the world he was describing. But quickly enough he became the story. In his first foray, recounted in Out of My League (1961), he got the opportunity to pitch against Willie Mays, Richie Ashburn, and others at a post-season All-Star game in Yankee Stadium. Editors at Sports Illustrated, which had recently been overhauled from its yachting and polo beginnings into a more populist form, took note and gave him free rein for more articles on swimming, golf, and other sports, featuring himself as audience surrogate. Tom Wolfe heralded Plimpton as part of the submerge-yourself-in-the-story movement of participatory nonfiction writing he called the New Journalism.

The big breakthrough into a wider popular culture came with the best-selling success of Paper Lion in 1966, in which Plimpton, dressed in shoulder pads, helmet, and a shirt with a giant “0” on the back, quarterbacked for the Detroit Lions. While it wasn’t quite Hemingway at Pamplona, Plimpton took the lumps as well as the glory, as he would again some 10 years later (again for Sports Illustrated) trading punches with Archie Moore, an interesting showboat in his own right, who had been Light Heavyweight Champion of the World.

With Paper Lion Plimpton became not just a person but also an eponymous noun, joining the ranks of Captain Boycott, the Earl of Sandwich, and many others. As Plimpton! records in loving detail, he consulted with Woody Allen and then tried standup comedy, swung on the trapeze at the Ringling Brothers circus, sat in as goalie for the Boston Bruins, played basketball with the Celtics, and inserted himself into a host of other experiences, always the inept but game participant, eventually becoming a guest on The Simpsons. In the meantime he made TV advertisements for Intellivision, Mattel’s early game console, and popped up in the movies as well, most memorably in Howard Hawks’s last film Rio Lobo, where, as the credited “4th Gunman,” he is shot by John Wayne before hardly saying a word. A TV special called Plimpton! Shoot-Out at Rio Lobo quickly followed.

Part of Plimpton’s appeal as the not very gifted amateur was his tall, gangling New England look, complete with the Kennedy-like shock of dark hair combed across his forehead that remained a visual brand long after it had turned white. It conveyed an aura of innocent play and endearing vulnerability to the round of gawky public performances that made his name. At one point in the documentary his son Taylor reads a short essay Plimpton wrote entitled “Things Every Man Should Do Before They Die: A Wish List by George Plimpton.” So perhaps he should be credited with inventing the bucket list as well.

He was in fact a friend of the Kennedy family and, as the documentary shows, shared their love of rough-and-tumble sports as well as their hairstyle. Certainly his courage couldn’t be doubted, even if the precipice of public performance helped urge it along. When Robert Kennedy was shot in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel, he helped wrestle the gun away from Sirhan Sirhan — the one major public event in his life he never wrote about.

People turn into emblematic figures when we look back on their lives, but Plimpton prepared his own way, complicit in establishing a public image melding the different sides of his nature — litterateur and sportsman, highbrow and populist, elitist and everyman. Plimpton! the documentary includes ample testimony from friends, colleagues, and family, sometimes admiring, sometimes with a critical edge, about who he appeared to them to be. Through these voices the documentary also gestures at some psychological explanations: principally, how he disappointed his strict father in everything, including his inability to make any sports teams at Exeter, where he was finally thrown out three months before graduation. After that he turned Ernest Hemingway into a surrogate father figure. Various wives and children remark on how much easier it was for him to make warm connections with people outside rather than within his own family.

Exeter, like so much else in Plimpton’s background, was a family legacy stretching back into the 19th century. Another of his books, unmentioned in Plimpton!, and equal to or better than Paper Lion, has an intriguing relation to his own life and career. This is Edie: American Girl (1982), an oral history of the life of Edie Sedgwick, another descendant of old New England gentry. Plimpton assembled the book with Jean Stein, and it is tempting to see Sedgwick as Plimpton’s fatal other, a similar escapee from the world of tradition and privilege. Sedgwick was the first publicized of Andy Warhol’s “Superstars” — the name itself an ironic homage to the pervasiveness of movie celebrity. She appeared in several of Warhol’s films, created a personal style that was picked up on and elaborated by the New York fashion magazines, starred in Ciao! Manhattan as Susan Superstar, a vaguely autobiographical version of herself, and died, essentially burned out from drugs and alcohol, at the age of 28.

Sedgwick, like Plimpton, was both tempted by fame and plunged into all the excitement and self-display available in the media world. But, unlike him, she never seemed able to stand back with his degree of self-mockery, and so the world engulfed her. Like Norman Mailer, who created a character named “Mailer” in his nonfiction, which he could observe from his own authorial distance, Plimpton carefully calibrated the gap between himself as participant and himself as writer. But the desire to flash through the sky never slackened. His next book after Edie, not coincidentally, was Fireworks: A History and Celebration. Roman candles indeed.

Shares