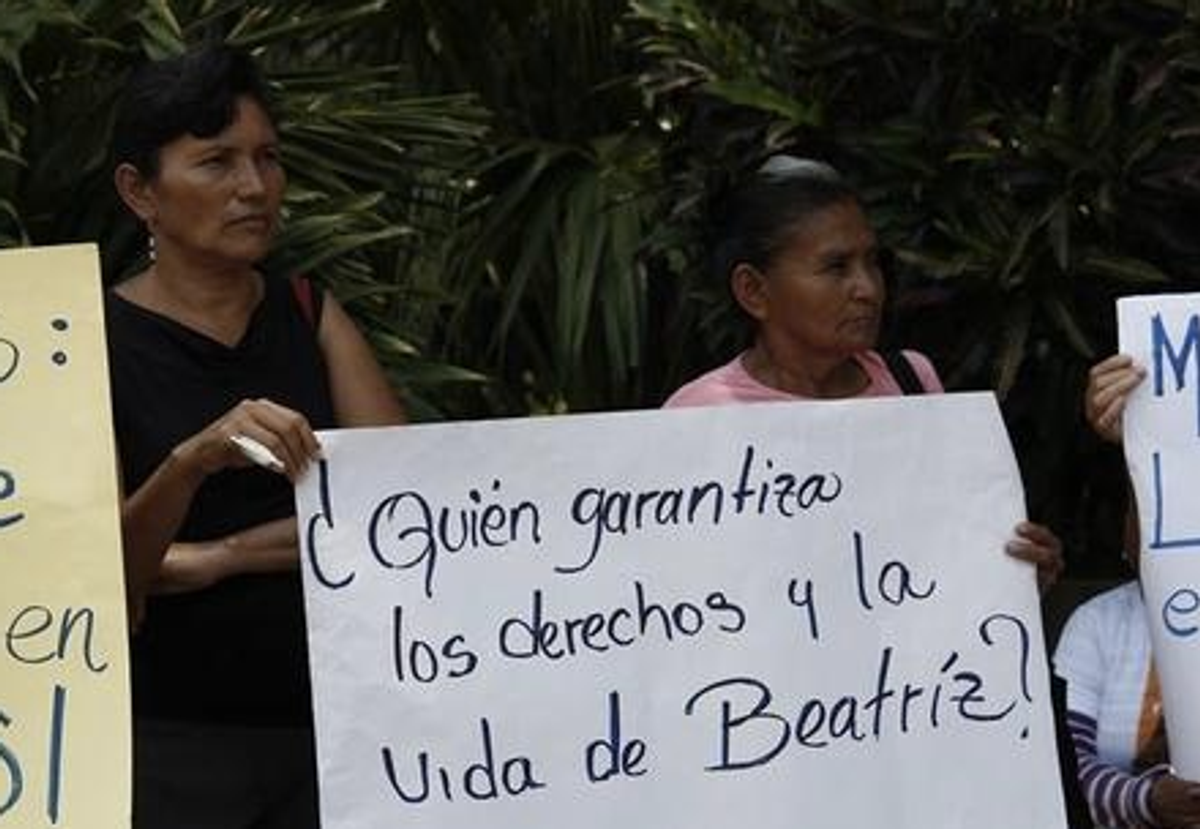

Last week, El Salvador's Supreme Court upheld the country's ban on abortion under all circumstances and denied the petition of a critically ill woman seeking to terminate a nonviable pregnancy. But while the court refused to grant the woman a therapeutic abortion, it also ordered doctors to closely monitor her health and “proceed with interventions” necessary to save her life.

As a result, the ministry of health approved a cesarean, a procedure that would, because the fetus was anencephalic and had no chance of survival outside the womb, effectively terminate the pregnancy. The C-section was performed on Monday; the fetus died hours later and the woman, identified in the press only as Beatriz, is now recovering in the hospital, her life no longer in jeopardy.

The legal workaround that allowed the court to both uphold the ban on the procedure while still allowing doctors to terminate a high-risk pregnancy has amplified debate in the country, and left many on both sides of El Salvador's abortion divide questioning the legal and semantic boundaries of the law.

Salvadorian antiabortion groups celebrated the court's decision and the health ministry's cesarean order, calling the procedure an "induced birth" that allowed the fetus to die of natural causes. But reproductive rights advocates view the doctors' medical intervention as an abortion, as the New York Times notes: “It is an abortion,” said Alejandra Cárdenas, legal adviser for the Center for Reproductive Rights. “They are interrupting an unviable pregnancy.”

But the ambiguity of El Salvador's law -- and the question of what constitutes an abortion in a country where abortion is banned -- is nothing new, as the Times goes on to report:

Salvadoran law makes no distinction between an abortion and an induced premature birth, said Evelyn Farfán, a professor of constitutional law at the University of El Salvador. So when the judges said that an intervention was allowed but an abortion was not, she said, they “modulated the terminology they used in the ruling to say the same thing without referencing the same word.”

Salvadoran obstetricians and gynecologists have developed their own procedural guidelines to fill the gap in the law, including defining the 20th week of pregnancy as the dividing line between what would be an abortion and a premature delivery.

In the absence of clear guidelines, motivation has become a defining factor, according to doctors: “An abortion is done with the intent of killing the baby,” José Miguel Fortín Magaña, director of the Institute of Legal Medicine, told the Times. “An induction is done with the intent of saving the mother.”

But the ambiguities of the law have not prevented El Salvador from prosecuting women: a report from the Center for Reproductive Rights reveals that 120 women were tried between 2000 and 2011 for abortion or "aggravated homicide" after terminating a pregnancy. Thirty-eight of them were convicted.

Shares