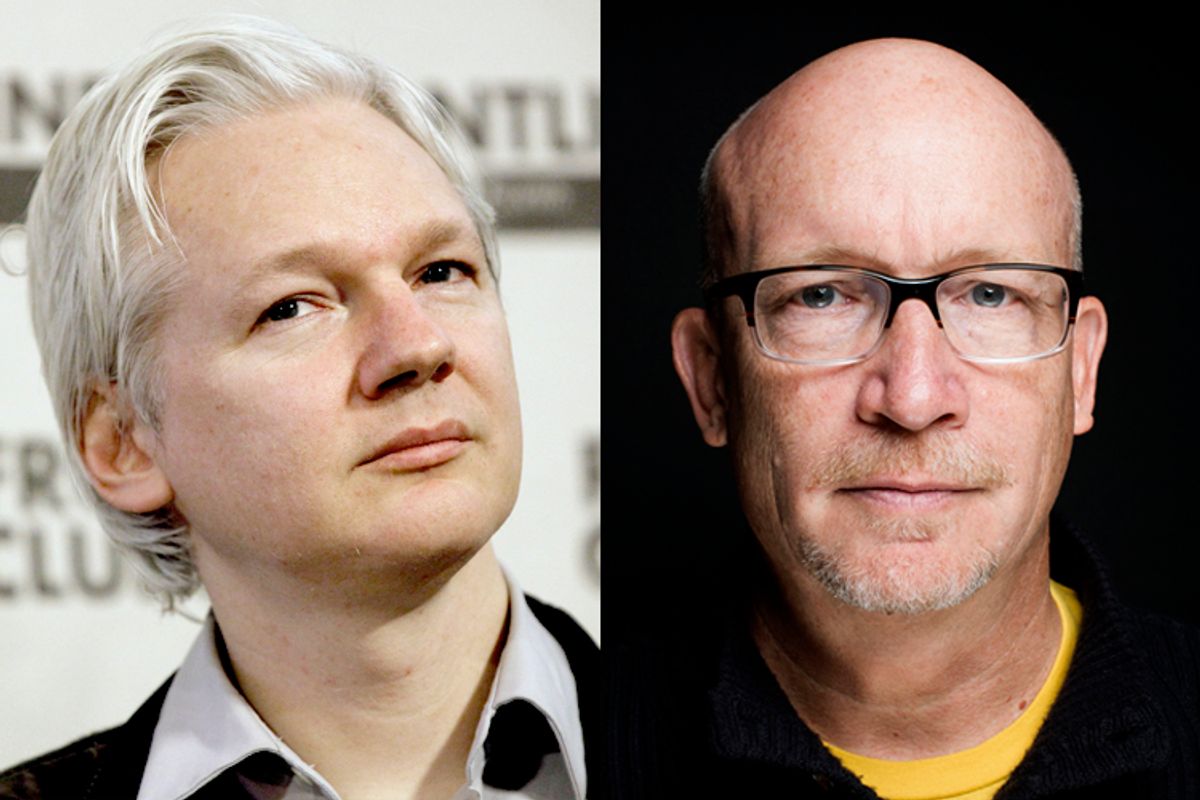

Last week the author and longtime war correspondent Chris Hedges, a leading figure in left-wing journalism, published a movie review as his weekly column for Truthdig. It’s not his usual beat, but this was no usual review. Hedges issued a thoroughgoing takedown of Alex Gibney’s documentary “We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks,” describing it as a work of “agitprop for the security and surveillance state,” designed to marginalize both WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and accused U.S. Army leaker Bradley Manning by depicting them as criminals. Especially in the current climate of heightened awareness around issues of surveillance and secrecy, this was clearly an attempt to kill the movie. And the review marked the public coming-out party, at least on this side of the Atlantic, of a campaign of vilification against Gibney and “We Steal Secrets” that began when the film premiered last January at Sundance and has scarcely abated since.

In an email to me just after the recent NSA surveillance revelations, Gibney expressed bafflement over this attack. “The film takes on the Obama administration for spying on us, over-classifying, keeping too many secrets, and reacting viciously to leaks (even though the Obama team admits there was no harm). It also shows that the leaks themselves exposed brutal behavior and crimes. Where is the evidence, in that, that I am a lackey of the military-industrial complex?”

Why, indeed, was it necessary for Hedges to direct a sweeping attack against the motives and integrity of a well-respected documentary filmmaker, rather than, say, clearly stating his objections to the film? Does he actually believe that Gibney, who won an Oscar in 2007 for calling the world’s attention to the Bush-Cheney torture programs in the groundbreaking investigative film “Taxi to the Dark Side,” has himself gone over to the dark side? Or is the whole thing some elaborate form of trolling? I don’t know the answers to those questions, but I do know that this episode reminds me of the way the old Marxist-Leninist left used to expend its most overheated invective in internal disputes, rather than at its actual enemies.

Hedges hasn't been the film's only critic -- an earlier back-and-forth in the British journal New Statesman featured Gibney and his executive producer Jemima Khan on one side, and Assange ally John Pilger on the other. And there’s a useful conversation to be had here, beneath the overheated rhetoric, about the way Gibney’s film renders a story that for many people is the political cause of the century as an ambiguous psychological drama. Instead of a stirring yarn about a generation-defining moral and political conflict, with Julian Assange in the starring role of David/Jesus/Joan of Arc, “We Steal Secrets” is a messy tale about imperfect people. It’s certainly legitimate to challenge Gibney on both his presentation of the facts and his interpretations of those facts, and some have done that. But I think the real problem lies in the kind of story Gibney tells, which strikes some people as deflating the moral imperatives of the situation and depicting the protagonists and antagonists as ordinary people.

Indeed, between his alarming accusations and peculiar misreadings of the film, Hedges raises some questions about the focus, tone and balance of “We Steal Secrets” that are worth discussing. In gradually moving from the larger political context and saga of derring-do around WikiLeaks to the story of Assange’s alleged sexual misconduct and erratic behavior, the film could be interpreted as suggesting a moral equivalence between Assange and the spooks and secret-keepers he has bedeviled. I’m pretty sure that’s not Gibney’s intention, but he could have done a better job of making that clear.

To some extent the film is a proxy war between two ambitious, independent-minded leftists with substantial egos, each accustomed to setting his own agenda. On one side we have Assange, the history-making hacker and journalist now holed up in the Ecuadorean embassy in London, with his freedom and reputation hanging in the balance. On the other we have Gibney, the Oscar-winning documentarian, who says he told Assange at their first meeting that he was making a movie about him, with or without the WikiLeaks pioneer’s cooperation. (That approach had worked on former New York Gov. Eliot Spitzer, subject of Gibney's "Client 9.")

Assange never sat down for an on-camera interview with Gibney, who has joked that he’s the only journalist in history not to get one. Even the reasons why that happened are in dispute. Assange says he decided early on not to cooperate, while Gibney says they had two lengthy face-to-face meetings and conversations through intermediaries, and that Assange demanded a fee of $1 million. I don’t know which of those versions is closer to the truth, but based on my conversations with Gibney and with people who know Assange, I suspect it was pretty simple: They got into an alpha-dog struggle for control of the situation, and neither would relent.

Collateral damage in this proxy war, if you will, is Bradley Manning, who is arguably the true tragic hero of “We Steal Secrets” and of this whole episode, but is unable to speak for himself in public. Hedges believes that Gibney presents Manning as a “pitiful, naïve and sexually confused young man”; Gibney has defended his presentation of Manning’s sexuality and gender identity issues in my recent interview with him and elsewhere. One important point not to overlook is that Assange and his supporters have a great deal invested in linking Assange’s case to Manning’s, when their situations are in fact extremely different. There’s considerable smoke around the possibility that if Assange leaves the London embassy the U.S. will try to extradite him. But the fact remains that as far as we know he has not been charged with any crime in America or anywhere else (the alleged sexual misconduct in Sweden remains an open investigation), whereas Manning faces the likelihood of spending much of his life behind bars for an act of conscience.

If “We Steal Secrets” depicts Assange in unflattering terms, as a murky and complicated character who has endangered the cause he fought for through his own conduct, Assange and his allies have struck back. WikiLeaks has released an annotated transcript of “We Steal Secrets,” very likely the work of Assange himself (which Gibney says is based on a pirated audio recording and missing large portions of the movie). Assange supporters on Reddit have posted a list of talking points designed to undermine the film and convince people not to see it.

Gibney has been assailed in tweets, comments sections and other social media as a peddler of tabloid sensationalism, a CIA stooge, a homophobe (for his treatment of Manning) and an apologist for U.S. state terror. Many people in Assange’s orbit appear to have convinced themselves that Gibney is in favor of prosecuting Manning and Assange, overtly or covertly supports the mainstream media campaign to demonize WikiLeaks and is a defender of government spying and secret-keeping. That either means that they haven’t listened to anything Gibney actually says or that they think he’s lying. While the film has received overwhelmingly positive reviews, it has only 4.3 stars out of 10 from IMDB users, a highly unusual split that may reflect an organized campaign by Assange supporters (whether or not they’ve actually seen the film).

In response to those charges, Gibney told me via email that “any reasonable viewer will see that the film casts the founding mission of WikiLeaks as praiseworthy and portrays its publication of the Apache helicopter video, the Afghan War Logs, the Iraq War Logs and the State Department cables (all provided by Bradley Manning) as an extraordinary historical act: one that fulfilled the important function of revealing to the public how war and diplomacy are conducted. The film also makes it clear that WikiLeaks is a publisher. A publisher should receive legal protection.” He added, “If Assange or WikiLeaks were to be indicted under the Espionage Act … I would be among the first to defend them.”

I am well aware that if this is a proxy war between Gibney and Assange, neutral ground is tenuous and difficult to hold. So let me be as transparent as I can. I know Alex Gibney and have interviewed him several times; I don’t know Assange or Hedges, but I have followed Hedges' work for years and have no beef with either of them. When I reached out to Hedges for comment, he wrote back politely to say that he had nothing to add to his published review.

Gibney’s film, Hedges writes, “dutifully peddles the state’s contention that WikiLeaks is not a legitimate publisher and that Bradley Manning … is not a legitimate whistle-blower.” As we’ve seen, Gibney specifically denies this, and I doubt many viewers will see that case made in the film. According to Hedges, Gibney presents Michael Hayden, who was CIA and NSA director under George W. Bush, as “a voice of reason” in the film. I would say that Hayden certainly tries to come off that way, but his actual effect is terrifying. Hayden's money quote in the film comes when he explains that he was not troubled by the infamous “Collateral Murder” video released by WikiLeaks, which shows civilians in a Baghdad street being gunned down from an Apache helicopter. By quoting that without further comment, Hedges seems to imply that Gibney is not troubled by those killings either.

Hedges’ review also leads readers toward the view that by interviewing Adrian Lamo, the hacker-turned-FBI informant who turned Bradley Manning in to authorities, Gibney signals his support for Lamo’s actions. Such a claim would seem strikingly odd to people who have actually seen the film, in which Lamo appears to be a damaged and unhappy person, seeking to justify an act of personal betrayal. (Would a reporter of Hedges’ experience actually prefer that a source as important as Lamo not be interviewed for the record?) No doubt that’s why Hedges never directly connects Gibney’s point of view to Lamo’s, instead linking them in a chain of insinuation. Something similar occurs with former New York Times editor Bill Keller, who appears in the film as both a hypocrite and a pompous ass, but in Hedges’ review appears linked to Gibney’s purported embrace of power.

But let’s get back to that troubling word two paragraphs up, “dutifully.” What is that supposed to mean? What duty was Gibney performing in making “We Steal Secrets,” and at whose behest? At the very end of the review, Hedges comes back to that, praising Gibney’s earlier films and then saying: “This time, Gibney was commissioned by Universal Studios -- owned by Comcast -- and paid to make a motion picture on WikiLeaks. He gave his corporate investors what they wanted.”

Once again, Hedges is careful to frame this as an argument that could be regarded as opinion or analysis -- isn’t it striking that this movie, like almost all movies, was funded by a major media corporation? -- instead of an accusation. But make no mistake, this is an attempt to attack Gibney’s integrity and sabotage his reputation, and to suggest that the filmmaker who exposed the horrific abuses at Bagram Air Force Base and the inner workings of Enron took a paid gig as a corporate hitman.

One of the questions I asked Chris Hedges was whether he really believes that Gibney made state propaganda on commission, or was just making a hyperbolic assertion to score political points. He didn’t answer, so I still don’t know. Gibney sees it this way: “If one accepts that Assange is a force for good, then any criticism of him represents a kind of fundamental evil. This acceptance of the notion that the end justifies the means is what [Guardian reporter and former WikiLeaks member] James Ball calls ‘noble cause corruption.’ If you believe that the cause of Julian Assange is noble, then you must be willing to tell whatever lie is necessary to defend him.”

Indeed, there’s a powerful strain of left-wing thought that insists we need heroes in order not to lose our idealism. I would speculate that for Hedges it’s worth sacrificing Gibney and his film to uphold the avatar of Julian Assange for a generation of young hackers and activists. In his article, Hedges compares Manning and Assange to Hannah Arendt, James Baldwin and Frantz Fanon (and even, later on, to Martin Luther King Jr.). That seems a painful stretch. More to the point, none of those people would have stood for accusing someone who is not your real enemy of being a traitor, a scoundrel and a turncoat for telling the wrong kind of story.

Shares