It’s fast becoming a cliché, but it’s nevertheless the truth: If Republicans plan to win the White House any time soon, they’re going to have to change. And that change will have to be more substantial than simply asking the Romney clan to ease up a bit on the whole public service thing, or churning out more Spanish-language campaign ads during the next election. To borrow one of the president’s favorite phrases, when it comes to an altered Republican Party, there’s got to be a “there” there. Singing some new lyrics atop the same old tune just won’t cut it. (Sorry, Senator Rubio.)

So the question is not so much whether the GOP should change but, rather, how? Two options commonly proffered are as follows: Republicans could follow the lead of Senators Ted Cruz and Rand Paul and push for even smaller government (I call this the “more cowbell” school of thought). Or they could look instead to the small but influential group of right-wing intellectuals claiming to offer a new path: the “conservative reformers.” The decision looks so simple. Either one step forward, or two steps back.

Spend some time reading the conservative reformers, though, and you’ll discover things are a wee bit more complicated than that. The choice isn’t quite so stark. Because rather than offering a fresh, new way to package conservatism for the 21st century, it turns out that the conservative reformers, whether they know it or not, are resurrecting an idea whose time has come, and gone, and perhaps now come again. They’re bringing compassionate conservatism back. Or at least they’re trying.

Before going any further, though, we should define our terms. What is compassionate conservatism? It would be an oversimplification to call it the conservatives’ version of Clintonism — but only a little. In a 2009 essay about the phenomenon for the National Interest, the New America Foundation’s Steven M. Teles described the basic conceit of compassionate conservatism as “an effort to shift the basic axis of partisan…from means to ends.” That’s a fancy way of saying that compassionate conservatism takes the welfare state for granted, whereas more doctrinaire conservatism (think Paul Ryan) seeks to burn it to the ground instead.

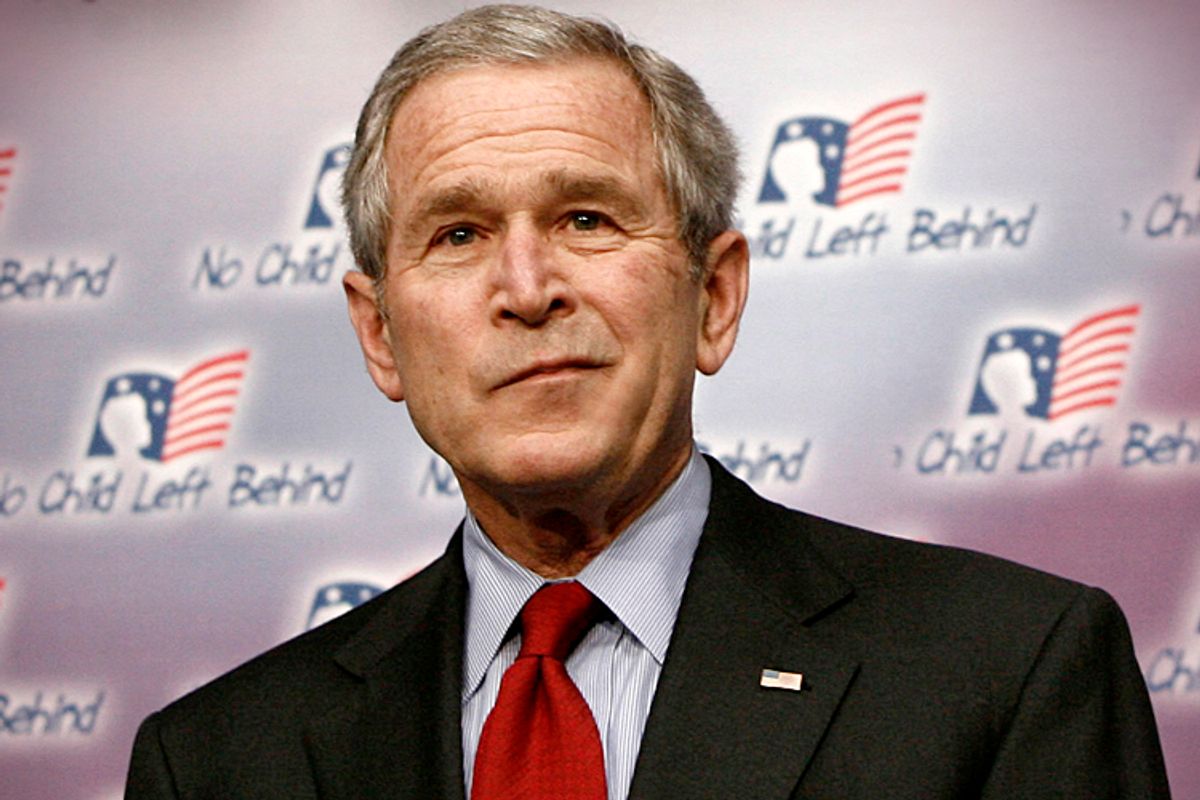

Most lefties consider “compassionate conservatism” to be little more than spin. But let’s stipulate that compassion is relative, that my bleeding heart may be your cold indifference, and that there’s a genuine distinction between a compassionate conservative like, say, George W. Bush and a more austere, doctrinaire right-winger like, say, Paul Ryan. Through left-wing eyes, that difference may be slight. And it may nevertheless result in bad policy (cough, No Child Left Behind, cough). But it’s no less real than the divide between the “pro-business” New Democrats and old fashioned liberals.

Because many activists blame compassionate conservatism for the failure of the second Bush presidency, however, its advocates are in something of a retreat. This explains why a small group of right-wing pundits — the New York Times’ Ross Douthat, National Review’s Reihan Salam, and Forbes’ Pascal Emmanuel Gobry chief among them — has shied from the label. For example, in their influential 2005 Weekly Standard essay, “The Party of Sam’s Club,” Douthat and Salam claim that compassionate conservatism “strikes the wrong note”; and in a recent Forbes post, “A Reform Conservative Manifesto,” Gobry writes that “there were many problems with compassionate conservatism” (though he does give Bush credit for trying something new).

But if we keep in mind the main sticking point between compassionate conservatives and their traditional colleagues — the idea that government is not everywhere and always the problem, that it can indeed be used to right wrongs and improve people’s lives — it’s hard to conclude that the conservative reformers are indeed offering anything substantially new. That’s not to say Douthat, Salam, and Gobry are pitching the same material, verbatim, that George W. Bush and Karl Rove did; Bush was never as obsessed with maintaining the traditional two-parent family as they. It is to say, however, that the differences between then and now are basically minor, and that the reformers are tweaking an old formula rather than remaking conservatism anew.

What’s especially troubling is that these changes, though small, tend to lean in the direction of making compassionate conservatism even worse. Whereas compassionate conservatives tried to woo minority voters by focusing on education reform, the conservative reformers prefer instead to lock in that dwindling subset of sometimes-Republicans: working-class whites. Douthat and Salam’s essay has much to say about “pro-family” tax reform — they even flirt with endorsing wage subsidies and Romneycare — and the struggling economic station of the working class. But when it comes to minority voters, the authors rather blithely conclude that the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina has rendered futile any attempts to court African Americans. Gobry, meanwhile, is too busy unpersuasively explaining why Ronald Reagan was secretly pro-government.

I don’t believe conservative reformers have so little to say on race due to bigotry. But the focus on lower-scale whites is not only strategically questionable (it’s far from clear that it’s “working class” whites who vote GOP) but, when coming from a group of thinkers who are ostensibly proposing something new, logically problematic. If we compare the conservative reformers to Grover Norquist or Paul Ryan, they do indeed look like a different, more reasonable — and, yes, more compassionate — breed of Republican. But that’s a consequence of the GOP’s sprint to the Right during the Obama years, not of a more substantial sea change in Republican opinion.

To be blunt: While it’s nice to see high-profile Republican pundits questioning their party’s recent commitment to cut government for its own sake, the conservative reformers are far from offering something the rest of us might consider genuine reform. What’s on offer, instead, is compassionate conservatism, a Bush-era idea, with less compassion and maybe a tax credit or two. What makes the whole exercise all the more disappointing is that even these reforms, meager and hesitant as they are, have picked up no traction among rank-and-file conservatives and other party elites. It’s enough to inspire a small measure of compassion, even among non-conservatives.

Shares