If I close my eyes and try to remember my mother, I can’t. I have no memory of her occupying the same space as myself. I have no memory of her voice talking or singing to me. I have no memory of her movement.

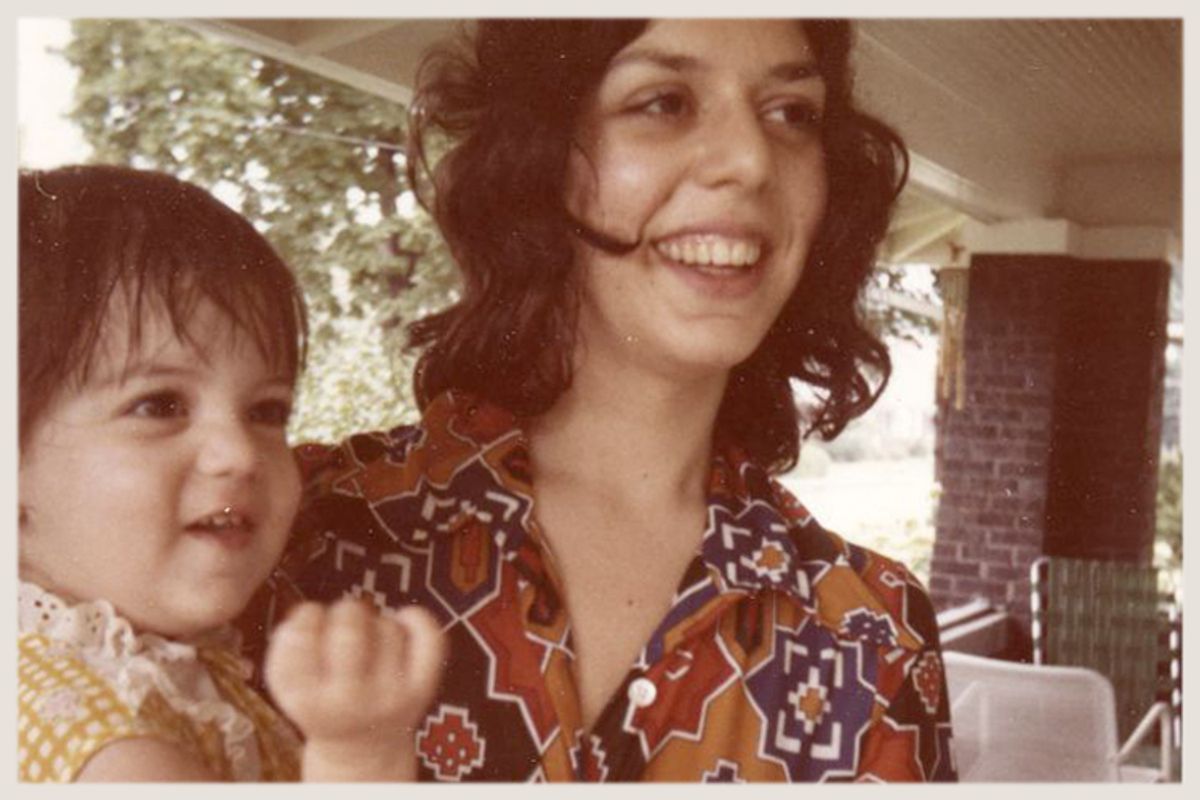

If I shut my eyes and make myself recall my mother’s face, I see the face I studied in photographs, portraits and snapshots. Here she’s almost always smiling. She’s almost always good-humored and warm, with her arm thrown around her shy younger brother or laid out in the backyard with a cat happily resting in the small of her back.

In the early pictures, she’s accomplished. Posing in bouffant hair and band uniform, she’s first chair clarinet. In cat-eyeglasses she’s focused on playing a piece of music on the piano, while her brother playfully taps the keys beside her. She’s on the grassy campus of Smith College in Northampton, Mass., on the day of her college graduation. Beside her my grandmother, Munca, beams with pride. In this last picture she is holding the long-stemmed red rose the college gave to each of the graduating girls in 1968. After years pressed between the pages of her Smith yearbook, the rose has turned dark brown and brittle.

In photographs with me and my father, she looks a little wilder, with loose hair and bright patterns, but she’s still smiling. In later pictures, taken at my grandparents’ home in rural Illinois just a few months before her death, she looks different. Her face has a yellowish tint. Her arms are skinny. As I look at these snapshots I have an urge to wrap my thumb and index finger around her arm to see if they will meet. And I wonder, now, if the smiles in these pictures were forced. I wonder too about the people who took these last pictures, her mother or father in the wood-paneled den that summer of 1973. Did they worry then over those skinny arms and the sincerity of that smile as I do now?

The truth is Barbara Binder Abbott had plenty to be unhappy about. Her husband had just left her for a man. He’d moved out, then later returned to their house on Adair Street but he was still in love with that man, frequently leaving my mother alone with me, then 2 years old. During my father’s long absence she’d started dating a patient from the clinic where she was employed as a social worker, spending days in bed with him, doing drugs, missing her work. This behavior had aroused the suspicions of her co-workers, causing her further worry. And she and my father were short on money. How did my mother think it would all turn out? How was this story supposed to finish? Why would she find her end under the wheels of a car on a foggy road in Sweetwater, Tenn.?

In his journals my father expressed deep guilt about this period of their relationship. He remembered punishing my mother when she complained about his affairs. He’d sometimes not talk to her for days. He lived off her salary then, supplementing his grad school fellowship with the money she made working at the clinic, before he eventually dropped out of school himself.

Though I can only remember my father hugging me and I can only hear my father’s voice when I shut my eyes and I still miss him every day. I deeply love him, but I feel a deep kinship with her.

After she died, my father and I lived in a world with few women. Both his lovers and his community of poets and writers were almost exclusively male. I always felt weird when hugged by a woman as a teenager and young adult. What were those soft lumps pressed against my chest? It’s still a weird sensation, though one I’ve grown more accustomed to.

As a teenager, I pulled on my father’s sweaters, jackets and jeans to wear as a way to feel close to him, but when I was curious about my future as a woman I always returned to the snapshots and portraits of my mother and her valedictorian statuette that sat on the top of the bookshelf in my grandparents’ guest room.

In my mother’s face I found my own: large brown eyes and rounded features, wavy black brown hair. I hoped that my reed-like figure might one day take on her feminine contours, so foreign in my world: hips, breasts, thighs.

When anyone spied a photo of her – I was proud to show off my three-ring album of family snapshots to any willing observer – that person would inevitably seize hold of my arm and exclaim wide-eyed, “You look exactly like your mother,” as though she was the first person to make this observation. I was grateful for the physical resemblance. Turning the pages of my album I’d reveal more photos, drinking up the reactions each provoked. I believed if I couldn’t remember my mother, I could at least look like her. She, this lost twin, my other half.

And then, when I later discovered and studied my father’s journals, as I read his reports of the hurts she sometimes endured while living with him, I realized that I might be able to relate with her emotionally as well as physically—the pain of loving a man who can never give you the kind of love he’s reserved for other men, the waiting at home for him to return from a night out, the search for that missing something, whatever it is, you might be able to offer that could win that exclusive love The questioning; the wanting; That peculiar and powerful loneliness. There was only one person who could understand that shade of longing my father provoked in me, and that person was the person I’d never know: my mother.

Whenever I sit down and read my father’s diaries, I get excited as if I were watching a favorite soap or reading a favorite novel. I have an urge to enter the narrative. I want to be the savvy best friend my mom should have had. The friend who’d take her aside and say, Forget this guy. He’s no good. He’s not giving you what you deserve. He’ll love other men and leave you at home. You can’t change him! He’ll barely bat an eye when you start dating other men, even when you start dating the least appropriate guy within reach, a schizophrenic patient named Wolf.

I want to say, Get away! Save yourself, finish your Ph.D and then marry someone rich and brilliant. I’m sure this is what her parents, my grandparents, would have wanted. Because I’m now the mother of a daughter, I can know this desire. Your brilliant daughter should be brilliantly matched.

But in reality, she loved my dad and the choices she made were her own to make. She couldn’t have moved to the suburbs. That was not Barbara. According to my father, she was intrigued by his interest in other men and, when they first got together, even encouraged it. She went out with him to the gay bars that dotted downtown Atlanta, even dressing in drag herself to lure men home. Both of them were committed to revolutionary ideals. They believed, as did many young people at the time, that society needed to be overhauled, that the rules of family needed to be thrown out, re-imagined. They believed that there should be room in society, even marriage, for experimentation and transgression. That said, what business did my mother have living in a commune or shooting up drugs in a wretched apartment? How could she leave me at home to bail a dead-beat boyfriend out of jail? She was smarter than that. She was a valedictorian.

If my mother had never met my father, or if she’d met him and then left him, finding herself a brilliant Emory grad student, I wonder if she might be living today. I wonder if she might have had that big family and the house full of animals I’m told she always wanted.

But then, where would I be?

Shares