In a Greek Orthodox Church annex in suburban New Jersey, I’m about to start my first morning of a four-week mind control summer camp. It is 1980. I am 9 years old. The classroom resembles an industrial park conference room, not the cavernous place of worship or brain reprogramming lab I had been expecting. The dozen other kids, aged 9-12, show the lack of interest reserved for Sunday school or detention. Doodling on their notepads. Staring into space. Except for me. I’m tapping my foot, both nervous and excited, because when you’re 9 and a little daydreamy and accustomed to following directions, controlling other people’s minds sounds like the chance of a lifetime.

If you don’t already know, the Silva Mind Control Method was founded in the 1950s, but taught in the 1960s around the same time as the Human Potential Movement. The HPM was an American subculture that yielded "The Inner Peace Movement," thinkers like Alan Watts and Jean Houston, and the Esalen Institute. Even among such radical minds, Jose Silva’s research stands out as unconventional and exemplary. The self-educated American parapsychologist trained his own children in deep relaxation, visualization and ESP techniques in effort to help them in school, and noticed remarkable improvement. In a 1953 letter to Dr. J.B. Rhine, renowned parapsychologist of Duke University, Silva claimed his methods led to his children’s improved mental acuity and test scores, and suggested he had found a possible key to human psychic performance.

Rhine’s response, that humans don’t learn ESP but rather are born with it, prompted Silva to perform more research based on the result he had seen in his own children. Thirteen years later, the Silva Mind Control Method was founded. It traveled an earnest journey through several decades of weekend workshops and night classes like the one my mother took in Northern New Jersey. My mother is no fool; she wasn’t a hippie or a ne’er-do-well. And yet, despite the strong work ethic of her blue-collar upbringing, she found the Silva classes persuasive and valuable enough to enroll me in the kiddie version even before I could braid my own hair.

I’d like to be able to blame my immersion in today’s personal growth landscape, as a writer and as an intelligent individual, on this choice of hers. But I can’t. The desire to feel exceptionally well, healthy and happy doesn’t get passed down, like old money, from one generation to the next. But it does shape-shift through American culture into provocative and profitable fads, as that populist magical thinking tome "The Secret" has proven. New Thought, New Age, Self-Help, Self-Improvement, Personal Transformation, Personal Growth; the list, and the marketplace, has only grown in the last 100 years. My question is, why?

A recent New York magazine article chronicled this genre’s journey from the margins to the mainstream of publishing with sharp insight. Once the New York publishing world merged self-help with journalism and science writing, the “worried well” became a legitimate readership to target, the article states. In short order, self-help stopped being a joke. To me, marketing strategy doesn’t tell the whole story. I can’t credit my mother’s interest, or my adult interest, or the millions of people who have taken on various Personal Growth systems, whether mindful meditation, positive psychology, even yoga, to the publishing industry’s ability to hook bigger readerships. The truth about why it’s so popular through the ages lies in my mind control summer camp memories. In particular, the direct experience that Silva facilitated for even its youngest participants: the experience of affecting reality. Quite plainly, it is thrilling.

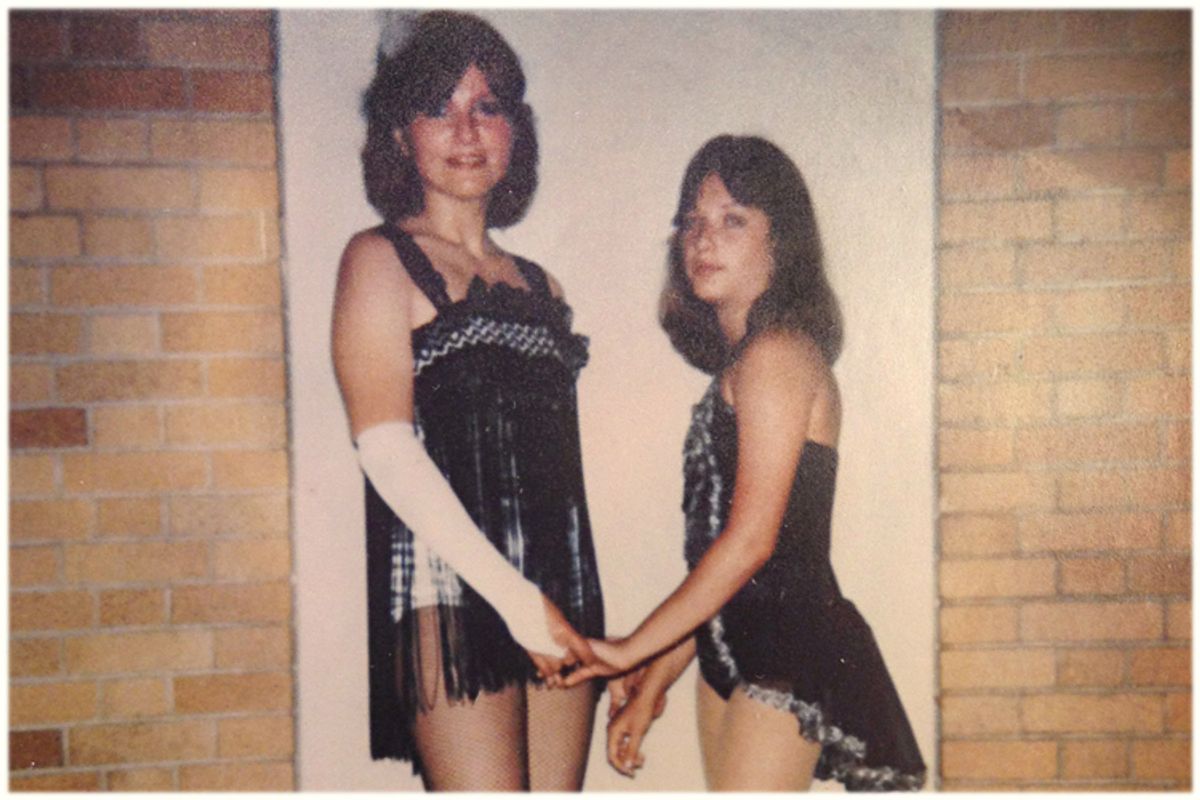

Like many other aspects of my 9-year-old life, I followed my mother’s plans for me — dance classes, Italian lessons, usually without too many questions. When, on a highway drive past shoe outlets and White Castles, she told me I would have the same instructor as she had in her Wednesday night Silva class, a woman named Mimi, I let her enthusiasm carry me through my trepidation. “You’ll play mind-strengthening games,” she said, “and positive thinking exercises. It’s fun. Mimi is just fun.”

I was familiar with "positive thinking." It had descended on our home a few months earlier. My mother had adopted Mimi’s signature expression for blocking out negative thoughts: Cancel, cancel. It quickly became a mantra she uttered after any casual insult I slung.

“That’s stupid,” I might say.

“Cancel, cancel,” my mother would say.

“The dance studio smells like feet; I don’t care for the meatloaf.”

“Cancel, cancel. Cancel, cancel.”

Clearly, my mother found the Silva class fun. She felt similarly about the Physiological Foundations of Health and Consciousness and Moving Away From Learned Helplessness classes she took at the politically progressive New School for Social Research. But while both styles of education enriched her and applied to her current phase of reinvention, Silva provided the perfect narrative structure for that reinvention: to be better and better, as the mantra went. Silva’s more practical, do-it-yourself narrative suited not only my mother, who was exiting the heavy lifting years of motherhood and entering the workforce, but much of New York City. Case in point: The New York Times on April 16, 1972, ran a story, "Can Man Control his Mind" on the Silva Method, the first paragraph of which provoked students to at least attempt mind control for years after:

"A visit to a Mind Control class in New York discloses more stockbrokers than bearded way outs and the dress style is closer to Brooks Brothers than to the East Village. A major New York company has sent all its top executives through the course and its president, a hard-headed businessman is seriously thinking of instituting an in-house training program for all employees. He refused to speak for the record, saying, We think there is something there, but I don't want to alarm our stockbrokers at the moment."

Silva’s popularity that had begun during my mother’s early parenting years only grew by the time she was ready to re-spin who she was in the world — a woman of the 80s, in the prime of her life. At 9, I was poised to spin a narrative, too -- my first one since reaching the age of social awareness, puberty and interest in getting a clue. Girls my age already shifted from telling the truth to telling secrets. Their dorky laughs became the giggles of their older sisters. I felt like I needed a manual for change. It may have been a coincidence, but every exercise of the Silva Method Youth Lecture Series tapped into my human impulse, and maybe that inherently American impulse, to author the exact life I wanted to lead. Very quickly, mind control camp seemed like the only manual I would need.

It helped that the classroom was pristine and corporate, that Mimi looked like she could be my neighbor. I took a seat in the second row and watched her scurry from desk to desk to introduce herself to the reluctant kids. Her speaking voice captured me; she was intense and joyful. I followed her strange directions without hesitation. Close my eyes, imagine the number “3” three times, and then watch it disappear. Then do the same with “2.” Then do the same with “1.”

“Next begin counting backwards from 10. Every time you say a number, see it in your mind. Then see two red lines crossing it out. When you see that red 'x,' say to yourself, ‘Cancel cancel.’”

The room felt quiet and focused, no longer uncertain and adolescent. She guided us back from 10 to one, and the images were easy to imagine. I simply thought of old movie reels where the numbers flickered in black-and-white before the feature. That familiar countdown became my own that day, and when I reached 0, Mimi said, “see yourself in 'Your Favorite Place.'” My mother was right. This was fun.

Our favorite place was wherever we felt most at peace, most happy, most alive. I scanned my mind for the right setting — my bedroom, my backyard — but neither location felt right. Home had become a bit of a train station since my mother started working part-time. Laundry was no longer put in my drawers but lay in a pile on the couch for me to fold. Dinner was casseroles, pre-made and ready to heat. Playtime was at other people’s houses. I needed a new environment to be my “happiest, strongest and smartest,” as Mimi cooed. Before I had time to worry about betraying my family, I found a green, expansive and completely private park in which to relax.

“This is your alpha state,” said Mimi, her voice a careful balance between monotonous and strong. “You can do anything here, you can be your best, most powerful, loving self. Choose your guardians now: Two people you trust will help you be your best self.”

My parents, too busy with life, didn’t immediately spring to mind as guardians. Subconsciously I sought to differentiate, so chose an aunt and uncle who recently began selling goods for Amway. They were kind with no children of their own yet, and had showed me plenty of attention. Once, they had taken me aside in my grandparents’ music room to say, with genuine love and care, that I too could "be whatever I wanted to be in this life." Even at 9, believing such big truths about myself felt a little hokey but, more deeply, it had a transforming effect. A new part of me hatched open and, as if with another set of eyes, I saw my own behavior, my own choices, as a force. It was my first taste of self- empowerment, and I liked it.

There were other empowering choices Mimi asked us to make while in the relaxed alpha state — which is an actual brain state dominated by hypnotic alpha waves. First, it was visualizing our own and other people’s good health. Visualizing auras around my own body; around my parents’ and grandparents’ heads. Visualizing auras around my guardians’ heads.

While in this relaxed, meditative state, I grew skilled at seeing auras light up around the heads of kids and neighbors I knew. I knew an aura was the glowing healing energy common to all living things. I had seen them in religious art, but also live each day when Mimi revealed to us her own.

She was seated at the front of the room, eyes closed after counting herself backward to the alpha state. I stared at her sweet face, lowered eyes, plump cheeks, lips parted. Then, very suddenly, a white circle appeared. It glowed, just like in the DaVinci paintings, around her head’s perimeter. I saw it brighten and then soften depending on where my eyes landed, on her black hair or the green chalkboard behind her. It looked like a faint, gaseous hat.

Her eyes popped open. “Did you see it?”

“I did,” I blurted. “It’s white.”

“You mean blue-ish white,” she corrected.

“No, I think just white.”

“Probably you couldn’t see the blue because of the green chalkboard,” she said.

“I didn’t see it,” chirped someone from the back.

“Me neither.”

“I saw light purple.”

People were saying conflicting things. Everyone was confused.

“Yes, yes.” Mimi clapped her hands. “It’s often a pale lavender or pale blue. Let’s move on. We’ll try it again tomorrow.”

Our lessons often ended like this.

We learned concentration exercises, some for memory, some for intuition, some for projecting our thoughts. These exercises required us to put three fingers together in what’s known as the Three Fingers Technique — the thumb, index and middle fingers press together to better facilitate or anchor our memory. We were to concentrate on sounds, feelings and, later, when we opened our eyes, vision. We learned to see all details in the room with only our peripheral vision. We practiced transmitting messages to other people while in this concentrated state. We practiced listening to other people’s silent thoughts and feelings. We practiced directing our energy towards good outcomes and towards what we wanted. We practiced rigorously, with the intent to feel better. Often I did—sort of. The elevated, dreamy sensations I carried around after class sometimes confused me. Why didn’t I feel this clear-headed all the time?

As it turns out, there were real chemical reactions and even medicine going on here. Meditation has since been linked to the Relaxation Response — a state that soothes neural structures involved in attention and control of the autonomic nervous system. Distance Healing (which includes seeing auras around loved ones) is a complimentary therapy often used in cardiac and terminally ill patients. As for sending our thoughts out telepathically, doctors on the cutting edge of alternative medicine frequently talk about non-local consciousness (mental activity outside the confines of the brain) as the gap to bridge in healing. I didn’t know it, but many of the Silva exercises of 1980 would become the basis for complimentary medicine 30 years later.

Less medical but no less memorable was the prayer-like saying we were asked to repeat three times at the end of class:

“Every day, in every way, I’m getting better and better.”

I know how this sounds, and some part of me, too, disapproves. My mind was being meddled with at a very a young age. My sense of self was being stretched and shaped like taffy before I was old enough to know it. If any summer camp tried this with my daughter I would withdraw her immediately, with only the slightest hesitation. I would hesitate for this reason: Maybe I was too young to know better, but I liked the comfort of the affirmations. I liked speaking words that felt true. I liked thinking about myself as strong more than I minded being embarrassed. I liked it not because I was unhappy or lost, but because, as studies on Oxytocin confirm, meditative affirmations release feel-good hormones and make us feel closer to everything and everyone in the world. Like the brain scans of nuns talking to God demonstrate, prayer makes us feel at one with the universe.

I knew mind control camp was different than the tennis camps and violin camps my neighbors’ children were attending, but I felt almost equally privileged. I carried the strange body of information alongside a brown bag lunch at my afternoon parks and rec summer camp. I put my three fingers together during group activities to help me win games, or at least feel like I could win games. I even set about practicing the techniques on my own.

The first time I tried was in the car. Mimi had suggested we try this simple exercise.

“Ask the car in front of you to move lanes. Just quietly ask, and do so by putting your three fingers together, and counting yourself back into the alpha state.”

On the ride home, I counted myself backward from 10 to one. My eyes opened to surrounding lanes of Gremlins and Beetles and Broncos. I noticed all the details: the dirty windshields and the worn tires and bent license plates. Then I stared at the driver. Please, driver of the chocolate brown Volkswagen Beetle, please won’t you move out of our way? Our car would like to pass your car. Would that be OK with you?

I was not terribly surprised when the brown beetle moved. But when the Gremlin moved, and then the Bronco, I felt a little strange, a little scared, but also very excited. My powers were real, I wanted to scream, and by all accounts, they were growing.

The act of mentally asking another to respond to you is a telepathy exercise. Although Silva didn’t use that word in the youth program, the idea took root in my 9-year-old mind: I was practicing psychic exercises! I had no idea psychic techniques were being covertly tested by the U.S. military in a now well-known spy operation (Star Gate: 1972-1995), and more than likely, neither did Jose Silva. But his interest in the experimental science put him at the leading edge of cultivating ESP among ordinary people. For better or worse, he was already teaching children.

The second time I remember testing out the techniques, the situation was not so benign. Two older, more physically developed girls from another town rode bikes onto my street, and started calling my friend and me names. They must have been 10 or 11. They circled and taunted us, waiting for us to cry or take an ill-advised swing. Instead, I put my three fingers together and tried to see their auras. I squinted my eyes. I looked closely at the crown of their heads in search of a bluish or white glow. It didn’t work. All I saw were their dirty ponytails and cruel enjoyment.

Though I felt tears welling, I persisted with mind control techniques. Please leave us alone. Please turn your bikes around and ride away. Please grow bored. Please disappear. I sent my gentle, silent messages all afternoon until the sky changed color. Nothing escalated, except my heartbeat. Eventually my mother called me inside. Those girls never returned. We were no fun to bother; we didn’t fight and we didn’t cry. But a part of me believed my directed concentration had helped the situation. I remained calm and focused. I didn’t panic or melt down. My secret powers hadn’t exactly saved me, but they hadn’t failed me either.

The third time the stakes were a bit higher. My mother’s part-time work had come home with her. Her employer was being taken to the cleaners in a nasty divorce, and because my mother handled his finances, a team of subpoena servers staked out our house for months. Attorneys advised my mother to avoid a court appearance at all costs, and though she had nothing to hide, she took their advice to be safe, to preserve the career she had only just started.

The subpoena servers were relentless. They rang our bell early in the morning, after school and into the evening. They sent flower arrangements with court papers tucked in the greeting card envelope. My mother routinely parked her car around the block, and I would lead her home through a series of shortcuts — paths through neighbors' yards, unwieldy thorn bushes and wooded areas, to get to the back door without being seen. Like the mind control exercises that seemed to change the situation around me, I took on the task of protecting my mother with similar diligence and expectation.

I don’t remember at what point I noticed the subpoena servers were following me home from school. They’d crawl along in one crappy hatchback or another. I recognized the way the car drove more than who was driving it. Sometimes, I knew even before leaving the building whether the car would be there, idling, waiting. I could feel it.

I often wonder if this heightened awareness was a side effect of Silva Mind Control’s techniques. Neuropsychologist Julia Mossbridge recently showed that humans seemed to have developed subconscious sensitivity to events in the near future. As lead author of a meta-analysis on physiological (or subconscious) premonition published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology, Mossbridge reveals our bodies detect the future. She speculates that it may be possible for people to learn to make this subconscious ability conscious, so that we can prepare for future events before they happen. Perhaps because I had been programmed to believe in my own extended mental ability, I walked home with my three fingers pressed together determined to change the stressful reality. This weird guy will not follow me home today. He will leave after seeing no sign of my mother. The weird guy will drive off as soon as I turn the corner. Sometimes it worked, and I’d turn around to see that the car was gone. Sometimes it didn’t, and the mustached bounty hunter drove right up behind me. Still, I never lost hope.

On weekends when my mother’s boss stopped by our house to chat, I would send him messages, too. You will figure out this terrible situation and your wife will stop bothering us. You will end this. It seemed my three fingers were constantly pressed together for one reason or another. At night, I would practice the techniques to “relax” into the alpha state and go to “my favorite place” just to be free from the stress. As escapist as these exercises may seem, I wasn’t imagining their usefulness. The direct experience of empowerment kept me steady. The reason why I didn’t have a nervous breakdown or start to slip in school was because mind control techniques showed me ways to cope.

The only disappointment was once I realized my techniques’ efficacy didn’t really extend to external circumstances. My mother’s boss lost the divorce; my mother lost her job. My enthusiasm died, my practices faded away. Skepticism and resentment of mind control camp’s falsities fueled me through adolescence and early adulthood. The system, the camp, the whole concept of mind control was easier to reject than examine. I tried blocking the experience out, but like so many people, I held on to the wish for a way to control the world around me. Not until I started a writing career, a meditation practice and a family did I understand the mind control techniques were never meant to control other people’s minds, but my own.

Shares