1. THE FIRST PUBLIC EXHIBITION of the papers and personal effects of the Chilean author Roberto Bolaño is the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB) exhibit “Bolaño Archive. 1977–2003,” the result of the Centre’s partnership with Bolaño’s widow, Carolina López, who along with her two children, Lautaro and Alexandra, constitute Bolaño’s heirs. The intensity of Bolaño’s posthumous fame — his second life as a cult literary idol — must be both mesmerizing and repellant to López, who for over two decades was the partner of an author for whom recognition was elusive. In the years since Bolaño’s passing, López has only rarely spoken to the press, primarily to dispel rumors. The exhibition, which will close just weeks before the 10th anniversary of Bolaño’s early death from liver failure, is not only an unprecedented point of access to his creative process but also a unique opportunity to investigate Bolaño himself: not the winsome headshot on the back jacket, not the collective dream of his admirers, but Bolaño the immigrant, the worker, the father, the artist, the man.

Readers tend to mythologize writers. A well-loved book has the power to elevate the author into a guru or totem. Bolaño’s death aggravated this process, forcing his readers to invent an origin story to explain the miracle of his work. He’s gone, so we seek his trace in his books and interviews. In the vacuum compounded by López’s silence, Bolaño legends have sprung up with weed-like rapidity, fueled by the combination of Bolaño’s sudden ubiquity and the relative paucity of biographical details. The author’s tendency to write about a doppelgänger protagonist — Arturo Belano, frequently simply “B.” — further muddies the waters.

Seeking a point of entry to Bolaño’s unforgettable prose — its curious power to dazzle and baffle, the pervasive, addictive mood that Francine Prose called his “microclimate” — we repeat the verses of his contradictory legend: He was an alcoholic like Bukowski. He was Alejandro Jodorowsky’s protégé. He was a heroin addict. He never did drugs. Hepatitis C, contracted from dirty needles, damaged his liver. He was arrested under suspicion of terrorism in Pinochet’s Chile, held in a secret prison, and escaped execution only because the men guarding him turned out to be his high school classmates. He was never in Chile. The prison story is a compensatory fiction prompted by guilt. Naturally a poet, he only began writing fiction to support his family.

With the CCCB exhibition, Carolina López draws this fantasia to a close, asserting control of her husband’s narrative. The exhibition has an air of correction, evident in prim assertions in the catalogue, as in this section by Valerie Miles, who worked closely with López on the exhibition:

Contrary to what has been repeatedly claimed about Bolaño the poet versus Bolaño the prose writer, his notebooks show that he had every intention of becoming a novelist [. . .] [Bolaño], whose exploration ofviolence and evil had probed the dark recesses of the human psyche, was in fact a happy man who experienced immense joy when he was writing. [. . .] It’s also obvious that he never used heroin and that his drink of choice was tea.

By displaying his private archive, López reclaims her lost husband, a restoration Miles explicitly endorses:

[López] belongs to another tradition, that of the practical genius whose role has been instrumental in creating an environment for a writer to work. She brought economic and emotional stability, the framework of a family, grounding, and encouraged him through the days of fasting in the desert when his manuscripts were being rejected by editors and agents alike. An author’s archives and the living memory of his family are undoubtedly the most trustworthy sources of information, and in the case of Roberto Bolaño he stated it clearly in one of the last interviews he gave: “My children, Alexandra and Lautaro, are my only homeland,” and “Carolina reads my books first, then Jorge Herralde” (his publisher).

“Bolaño Archive. 1977–2003” returns the story to Bolaño himself, whose vivid voice rings from each manuscript page in his tiny, neat handwriting, whose unflinching gaze stares from each photograph.

2.

The CCCB is located in El Raval, Barcelona’s university district, not far from Las Ramblas. At the exhibit’s entrance hangs a six-foot-tall excerpt from Bolaño’s 1993 poem “Musa” (“Muse”):

Musa, adonde quiera

que tú vayas

yo voy.

Sigo tu estela radiantea través de la larga noche.

Sin importarme los años

o la enfermedad.

Sin importarme el doloro el esfuerzo que he de jacer

para seguirte.

Porque contigo puedo atravesar

los grandes espacios desoladosy siempre encontraré la puerta

que me devuelva

a la Quimera,

porque tú estás conmigo,Musa,

más hermos que el sol

y más hermosa

que las estrellas.Muse, wherever you

might go

I go.

I follow your radiant trailacross the long night.

Not caring about years

or sickness.

Not caring about the painor the effort I must make

to follow you.

Because with you I can cross

the great desolate spacesand I’ll always find the door

leading back

to the Chimera,

because you’re with me,Muse,

more beautiful than the sun,

more beautiful

than the stars.

The exhibit is arranged in a series of low, dim rooms with dark red walls that echo with the atmospheric soundtracks of four film installations. The overall feeling is cave-like, grotto-like. The first film, “Close phantoms, family demons,” is comprised of interpolated footage of Hitler, the 1968 Tlatelolco Massacre, and the fall of Salvador Allende, emanating in waves across a room-sized curved screen, which the program calls a “reversible landscape.”

Beyond this rumbling curiosity, the first archival materials appear under glass: Bolaño’s infrarealist manifesto Déjenlo todo, nuevamente (Give It All Up Again), his first collection of poetry Reinventar el amor (Reinventing Love), and an anthology of infrarealist poetry Pájaro de calor (Bird of Flames), all published in Mexico City in the late 1970s. They are harbingers of the exhibition’s strangely destabilizing impact, for each book is not only a piece of the Bolaño archive, but also a physical piece of The Savage Detectives, the novel that won the 1999 Rómulo Gallegos International Novel Prize and catapulted Bolaño to international renown. The Savage Detectives chronicles piecemeal the adventures of the infrarealists Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima, shadow selves of Bolaño and his friend Mario Santiago, who founded the poetry movement together. These items, like the books and manuscripts that follow, are both evidence of Bolaño’s creative process and realized pieces of his fiction, stories that the reader could touch, if not for the protective glass.

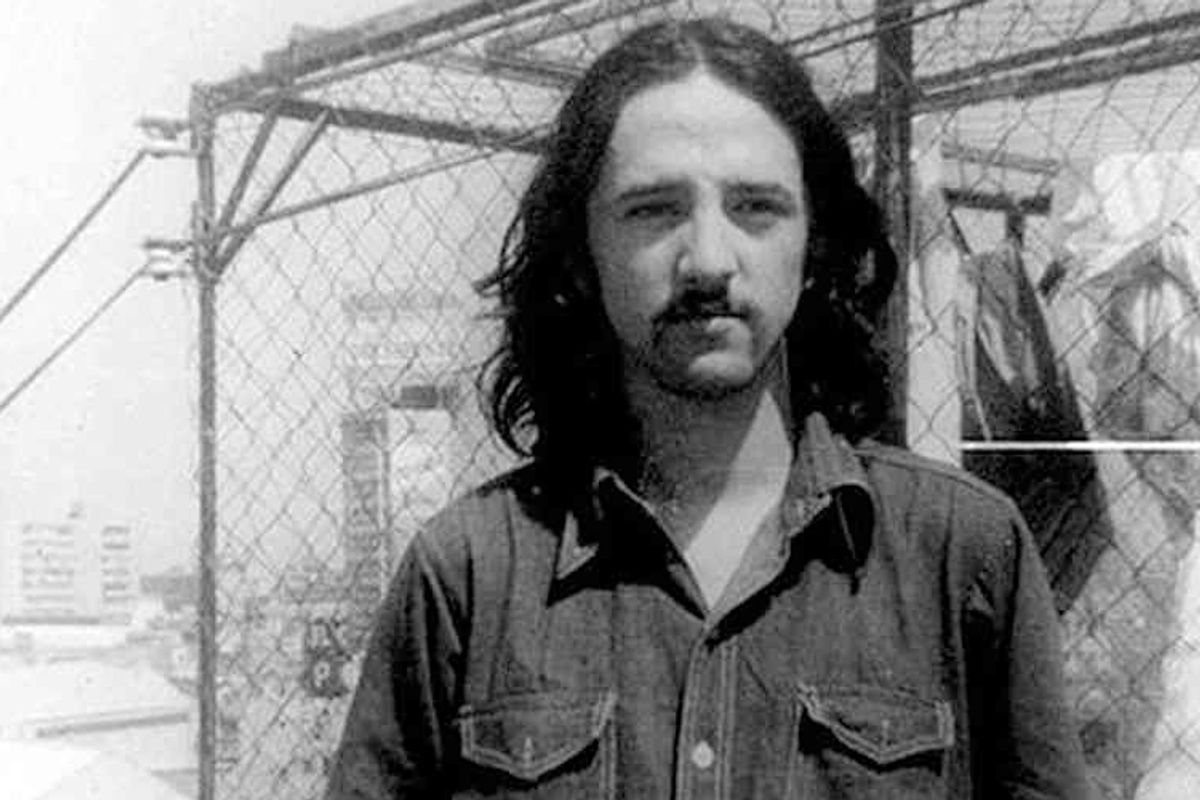

As if in reaction to the temptation to lose oneself in these unreal materials, reminders of reality hang above each glass case: illuminated photographs of Bolaño, like stills from a forgotten film. Many of the pictures were taken in photo-booth kiosks, vertical rows of identification pictures that the author repurposed to fit a given mood. The man as we know him from the backs of his books is middle-aged, unflinching, a little sad. Here is boy Bolaño, impossibly young, with flowing black curls and double bridge glasses. He sits at a restaurant and in a park, on a city street, with other boys, with girls. In the background are palm trees, cityscapes, flowers, someone’s apartment. He broods, glares, and smokes; he smiles, looks away. In a particularly indelible set of images in the third room, he embraces López and infant Lautaro, three faces crowding the frame with bittersweet smiles. The visitor can dream the items in the glass cases — Bolaño’s collection of science fiction paperbacks, his carefully organized notebooks, the articles he clipped from newspapers — but then, looking up, must float back down. Roberto Bolaño is an idea, but he was a man, a person who smoked on balconies and took his children to the Louvre, as shown in a photograph from the year before his death.

The other film installations are animated responses to the author’s fictions. One animates Bolaño’s tiny handwriting, complete with pencil-scratching sound effects. Another redraws the manuscript illustration, viewable in another case, which he drew beneath the last lines from his novel Antwerp, written in Barcelona in 1980:

Of what is lost, irretrievably lost, all I wish to recover is the daily availability of my writing, lines capable of grasping me by the hair and lifting me up when I'm at the end of my strength. (Significant, said the foreigner.) Odes to the human and the divine. Let my writing be like the verses by Leopardi that Daniel Biga recited on a Nordic bridge to gird himself with courage.

Throughout, the exhibition attempts to give the viewer a window into Bolaño’s artistic process. In the first room several tables are papered with typed copies of Bolaño’s exhaustive lists of writers, artists, filmmakers, musicians, and philosophers. A representative example reads: “[Ambrose] Bierce, Jean-Pierre Verheggen, Wilhelm, Sylvia Plath, Mary Shelley, Joe Haldeman, H.G. Wells, Ursula K. Leguin [sic], Alfonso Reyes, Mario de Sá-Carneiro Caranguejola, Dashiell Hammett, Bertran de Born, Juan Marsé, Seneca, Cardenal, Bertolt Brecht, Chandler, Ellin, Ted Berrigan.” Later, another table is covered in a collage of printouts of Bolaño’s internet research on Ciudad Juárez, pages of the peculiar melancholy of a bygone digital age. A television with headphones offers “Bolaño X Bolaño,” the author’s appearance on Chilean television in the late 1990s.

The exhibition’s main attraction is its huge collection of manuscripts, notebooks, and cosmographic maps, drawn in Bolaño’s neat cursive. One does not walk through “Bolaño Archive” so much as one swims, floating past the surreal objects that connect Bolaño’s fiction to reality. His student identification cards; his copy of the war strategy board game Third Reich, from which his posthumously recovered novel takes its title; the emblem of Estrella de Mar, the campground where Bolaño worked as a janitor, an experience recounted in The Savage Detectives. Passing these objects gives the Bolaño devotee a peculiar feeling, something like what the author describes in the short story “Sensini” as “[a] feeling like jet lag — an odd sensation of fragility, of being there and not there, somehow distant from my surroundings.”

Here are the objects that were translated into fiction and thus into eternity, the visitor thinks, running her hand along the tops of the glass cases. In the exhibition’s final room wait the most melancholy objects: three pairs of Bolaño’s glasses shrouded in gentle, intimate light. The visitor may be moved so deeply that she stands suspended in front of the case for a few minutes, trying and failing to swim on.

3.

I discovered Roberto Bolaño on an evening in December 2008 shortly after my 24th birthday, when I stumbled into the 2666 release party while out for drinks with colleagues from a publishing internship I’d held the previous year. The party was hyped by its organizer, Farrar, Straus and Giroux and Paris Review editor Lorin Stein as “the most chaotic fucking book party ever thrown, [which] will make all other book parties look like fucking well-oiled teutonic machines.” It took place at a bar called Plan B in Alphabet City. When we arrived, the line was so long that it looped around the corner and spilled out onto Avenue B.

“What’s going on?” I asked.

“It’s a release party for a new book, 2666,” someone told me. “By Roberto Bolaño. He’s South American. And dead.”

“Who?”

“I haven’t read it but everyone says it’s amazing,” she said. “Jonathan Lethem wrote an incredible review in the Times.” I filed this information in a back file in my brain. My interest was barely piqued. In those days, it seemed I would never be piqued again.

2008 was my fifth year in New York City. The city’s glamour had long since become more of a taunt than a promise. I was at work on my first novel, a book everyone told me I was too young to write, and single for the first time since I was 14 years old. I wanted to lose myself in writing and carousing, but no one would publish my stories and I was a hopeless casual lover, two realities that filled me with rage. I had always turned to literature for guidance, but the voices that had led me before — Edward Gorey, William S. Burroughs, Truman Capote, David Lynch, Marilynne Robinson — began to ring hollow. When I returned now to words that had once brought me solace, my reading was fraught with a kind of moral exhaustion. For someone who has spent her life within books and films, this was a horrible development. Sometimes, for no apparent reason, I found my face hardening into a rictus of anger.

So I went out with my friends, full of dumb hope: maybe tonight’s the night! I just wanted to catch someone, the way I had watched everyone else catch everyone else. I took my place in the long line as I had on so many nights before.

When we finally made it inside, the light was red and the furniture was black. There were no copies of the book for sale, and all of the free drinks were gone, too. I sat in a booth with B, an editorial assistant who had left his job at the publisher, and E, a fellow former intern. In my days at the publishing company, B had always been careful to give me interesting tasks, writing catalog copy and author letters, instead of just relegating me to envelope stuffing and endless photocopy jobs. I thought this meant that he respected me, even — it makes me cringe to think it now — that he considered me an equal.

These were my friends, I thought, and asked B a humiliating question.

“You’re older than me,” I said. He was 28. “Does it get easier?” My jaw hurt from trying to control my curdling expression. B inclined his head.

“Yes, a bit,” he said. “Around 26 you start feeling like less of a grub.”

“A grub,” I said.

“Yes, it can be a grub-like time. Although,” B said, turning to smile dreamily at E, “Not for you. You’ve always been a butterfly, haven’t you?” E giggled, scooting closer to him.

Soon the conversation was theirs alone, and I left, confused, stung with longing. How was it so easy for them? What had I missed? The evening burned into my memory. The novel’s strange allure and fervent admirers stayed with me long after I limped home to drink bourbon on ice in my kitchen window.

I didn’t know it yet, but B was right. It was going to get easier. The unguent was right there beside me in Plan B. Soon I acquired a handsome edition of 2666, which cleverly packaged the book’s five parts as three paperbacks in a stiff case. From the first page, Bolaño’s voice was addictive, demanding attention like a lurid, beautiful photograph. But he was comforting, too, wise, funny, sure-handed. He was smart. He was honest. He was brave.

I fixated on Part Three, “The Part About Fate,” which follows the unlikely adventures of a black reporter sent to cover a boxing match in Santa Theresa, Bolaño’s name for Ciudad Juárez. The reporter, Oscar Fate, records a kind of sermon given by a Black Panther at a Detroit church: “The sun has its uses, as any fool knows, said Seaman. From up close it’s hell, but from far away you’d have to be a vampire not to see how useful it is, how beautiful.” How did he nail the voice? How did he know what a man like this would say to a crowd of believers?

The world of the book swallowed me up like a great dark wave. That Christmas, I became involved with an older man. He treated me badly, which must have been what I wanted. I read 2666 waiting for him in bars, riding the train, sitting slumped in libraries. Bolaño’s voice had a curative power. Slowly I came to understand that the older man would not be kind to me, that adults find what they want, that what this one wanted was my unhappiness. I started to understand what I wanted. My fear and malaise broke in Bolaño’s hands. As long as I kept reading, I could keep going.

When the final semester of my MFA began in January, I enrolled in Francine Prose’s “Craft of Fiction” class. Her syllabus included four Bolaño stories, from the collection Last Evenings On Earth.

“Has anyone heard of this author?” she asked. Shyly, proudly, I raised my hand. I was grateful to be the only initiate.

I have not left him again. In dark times, I turn to Bolaño’s books like a Christian to the Bible. It is too much to ask of the modest Chilean, whose sole vanity was his devotion to his work. But he has never disappointed me, giving succor and clarity, teaching me how to accept change. The end of “Sensini” became my dream of happiness:

Suddenly I realized that we were at peace, that for some mysterious reason the two of us had reached a state of peace, and that from now on, imperceptibly, things would begin to change. As if the world really was shifting. I asked her how old she was. Twenty-two, she said. I must be over thirty then, I said, and even my voice sounded different.

Something strange happens when a reader falls in love with a writer: the reader finds a place for herself in his sympathies, thinking of him with tenderness. The strange kinship we call fandom is a secret, one-sided friendship nurtured in words.

Through change, Bolaño stayed with me.

B., I began to call him, to myself.

4.

Only the very first objects included in “Bolaño Archive. 1977–2003” are artifacts of Bolaño’s life in Central and South America. 1977 was the year of his arrival in Spain. The exhibition not only charts the author’s biography — an effort to correct the cloudy record encapsulated in an exhaustive chronology charted on a massive timeline — but also explores his relationship with the Catalan cities that he called home.

The exhibition is organized in three successive environments. The first, “The unknown university. Barcelona 1977–1980,” covers Bolaño’s time in the Catalonian capital. The second, “Inside the kaleidoscope. 1981–1985,” focuses on his time in Girona, an inland city to the north of Barcelona, where he met Carolina López in 1981. The last, “The visitor from the future. Blanes 1985–2003,” covers the two decades Bolaño spent in Blanes, where he lived from the year of his marriage until his death. Projected photographs of these places divide the exhibition space: of Carrer Tallers, not far from the CCCB, where he lived at number 45; of 29 Carrer Caputxins in Girona; and of 23 Carrer del Lloro in Blanes, where Bolaño and López lived, worked, and raised their children together.

Also in the Blanes slideshow are images of Joker Jocs, where Bolaño bought the war-strategy games described in The Third Reich, which he loved to play with his son Lautaro, and Café Terrassans, where he often lingered over coffee and cigarettes. Standing before the photographs of Blanes as they melted into each other, I couldn’t seem to maneuver my shadow out of the path of the projector. No matter where I stood, my shape was stained onto Blanes.

Like everything else in the exhibition, it was a strange image that was also true. In the spring of 2012, I won a grant to travel to Blanes to research Bolaño’s life there. In the years since finding Bolaño, I had become preoccupied with the problem of his biography. Reading his work kept drawing me closer. I wanted to make a pilgrimage, an embarrassing desire that I couldn’t shake, but where to? I sought clues in Between Parentheses, the collection of Bolaño’s incidental writing. Los Ángeles, Chile, where he was born? Mexico City, where The Savage Detectives is set? Neither Mexico nor Chile are presented in Bolaño’s writing as homelands; they are lost dreams, mourned past lives. When Bolaño wrote about home, he wrote about Blanes:

[A] town or small city that despite its problems, despite its defects, is tolerant, is lively and civilized, because without tolerance there is no civilization [. . .] That’s what Catalonia has taught me and what Blanes has taught me among many other things that I’ve learned here, the most important of which is to take care of my son, who is a citizen of Blanes and a Catalan by birth and not by adoption, like me.

The above quotation is from “Town Crier of Blanes,” an address Bolaño was invited to give at the 1999 New Year’s celebration. “The urban geography of Blanes,” he writes, “[. . . ] is the urban geography of the soul, [. . . ] and maps like those are made so that the heart doesn’t get lost.”

So I had to go to Blanes. But I had no idea what I would find there. I traveled openhearted, dreaming of finding a place that would offer me a way of understanding B. I mainly expected to take pictures.

Blanes is an hour and a half north of Barcelona, easily reached by a delightful train ride alongside the ocean. When I arrived, the town’s beauty surprised me. Blanes marks the beginning of the Costa Brava, so named for the wild rock formations in the ocean near the long beaches. Sa Palomera, a large rock formation crowed with a Catalan flag, separates Sabanell Beach to the south from the Bay of Blanes to the north. Just beside the beach lays the Paseo Maritimo, immortalized in The Third Reich:

The Paseo Maritimo is empty except for a shadow that vanishes along the boardwalk toward the tourist district, which at this time of day (but what time of day is it?) resembles a milky gray cupola, a bulge in the curve of the beach. At the other end, the lights of the port have faded or simply gone out. The asphalt of the Paseo is wet, a clear sign that it has rained.

Early in his time in Catalonia, Bolaño worked as a vendor on the Paseo, selling maritime trinkets. The vendors are still there, interspersed with whitewashed restaurants advertising Irish coffee and Cuba Libres. In honor of The Third Reich, I stayed at the Hotel Costa Brava, which in Bolaño’s novel is a luxurious and spacious establishment on the beach run by Frau Else, a mysterious and beguiling German woman. The real Hotel Costa Brava is small, 15 minutes’ walk to the water and run by an querulous elderly couple and their adult son: my trip’s first unraveling of Bolaño’s invention.

Bolaño knew Blanes intimately. He used its changeable character to great noir effect inThe Skating Rink, in which Blanes is called “Z”: “the storefronts seemed to be elements in a vast camouflage operation. The bare streets were not where they should have been, and in some streets the flow of the traffic had altered substantially.” Walking in the pretty beach town, I was struck by the dissonance between this image and the bright, sunny place in which I found myself. I felt a similar clash driving around Los Angeles looking for the shooting locations of Mulholland Dr. Bolaño saw the darkness beneath the resort veneer, one I could glimpse, too, if I read the local newspaper, Diari de Girona, for which he wrote, or asked questions of the countless unemployed young Catalans looking for something to do in the tiny medieval streets.

I did not expect to meet anyone in Blanes who had known Bolaño. Before leaving the United States, I had exhausted every contact I could find or beg off better-connected friends, corresponding with Bolaño’s first English translator Chris Andrews, an Australian academic; Bolaño’s second English translator Natasha Wimmer; Barbara Epler, president and publisher of New Directions, who brought Bolaño to his American audience; Lorin Stein; and Bolaño’s agent, Andrew Wylie. These sources and others helped me or they didn’t. They were kind or curt, but slowly a web of contacts began to take shape.

Stein and Epler sought to connect me to Bolaño’s friends Rodrigo Fresán and Enrique Vila-Matas, neither of whom was able to meet. The former’s email address had expired, the latter was in Brazil. Wimmer put me in touch with Cristina Zabalaga, artist and author of Pronuncio un nombre hueco, a fictional retelling of Bolaño’s life. Zabalaga had once lived in Blanes as research for her novel, and connected me to Cristina Fernández Recasens, another writer from Blanes. The two Cristinas — Cristina the first and Cristina the second, as I briefly thought of them — were instrumental in helping me to develop a spatial sense of Blanes and generous with their own Bolaño archives: the addresses of his apartments, the places he had worked, the room named for him at the public library.

I went into bakeries and shops, possessed with romantic zeal, asking strangers if they remembered Bolaño. To my great surprise, almost everyone did: the owner of the bakery beneath his first apartment in Blanes, the proprietress of the bookstore on Calle Anselm Clavé. They recalled his giant curly hair and massive glasses, his habit of hiding behind a book. Roger Perales, Blanes’s tourist attaché, told me that in the past year over a hundred visitors had come to Blanes in search of Bolaño artifacts. “We should build a museum, but of course there is no money,” he said sadly, then drew me a map of places to visit.

I was in Blanes for five days. In that time I circled Bolaño’s sites, paced under his old studios on Carrer del Lloro and Carrer de l’Aurora, climbed the tall hill in the north of town and walked to the end of the Paseo Maritimo. I felt close, but not quite there. I wanted more of him and his Blanes, but time was short. Was this a pilgrimage, I wondered, or a vacation?

Then, on my last morning in town, Fernández Recasens emailed me. “You can visit Narcis who was Bolaño's friend,” she wrote. “He has a video renting shop in Los Pinos called Videoclub Serra. You can tell him that I sent you.”

The name was familiar. I went back to “Town Crier of Blanes”:

And then there’s Narcís Serra, who ran and still runs a video rental store in Los Pinos and who was and I imagine still is one of the funniest people in town and also a good person, with whom I spent whole afternoons discussing the films of Woody Allen (whom Narcís recently spotted in New York, but that’s another story) or talking about thrillers that only he and I and sometimes Dimas Luna, who back then was just a kid doing his military service and who now runs a bar, had seen.

6.

I met Narcís Serra in his movie rental store Videoclub Serra, which is located in the Los Pinos section of Blanes, the same neighborhood where Bolaño first lived. Videoclub Serra bears all the markers of a cinephile paradise, with twin broad front windows bearing an intricate mosaic of DVD cases of disparate films, the documentary Inside Jobnestled between Korean horror movies, Spanish romantic comedies, and several films about the Dalai Lama; Serra is an ardent supporter of Tibetan independence. A giant poster of a scantily clad Adrianne Palicki blowing a kiss advertised a film calledProblemas de Mujeres. The interior was dim and quiet, with the reverent feel of a library, countless DVDs in matched gray and blue cases lining the walls and shelves.

Serra, a tall man in his 40s with silver hair, has lived in Blanes all his life. He has owned his store since 1987, but does not expect his business to last much longer. In Blanes, just like everywhere else, people are increasingly less likely to leave the privacy of their homes to rent a movie when they can so easily do it online.

Serra met Bolaño in Videoclub Serra in the early 1990s.

“Soon, we were very close,” he told me. I soon understood the naissance of this quick intimacy: Serra is a charming and indefatigable conversant, constantly launching forth on a new discussion of the current cinema. Bolaño, as he told me, was a natural listener, fascinated by everything, more than happy to stand in the Videoclub for an entire afternoon, just talking.

For over a decade, the two men spent hours together nearly everyday, discussing “politics, the economy, women, films, books, sports.” Serra described Bolaño as a consummate watcher, fundamentally reserved, with an excellent sense of humor. Above all, Serra stressed, Bolaño was insatiably curious. His desire to penetrate closed worlds, so present in his writing, was also a determining force in his life. When Bolaño first moved to Blanes in 1987, Serra told me, he often spent hours in a bar notorious for its clientele of junkies and cocaine addicts, just observing them. The drug users accepted Bolaño because he was so calm and unobtrusive, content to simply sit among them, drinking coffee, smoking cigarette after cigarette, and reading. Bolaño read everywhere, Serra said: at bars and restaurants, on the beach, while waiting to pick Lautaro up from school. This was a trait that everyone in Blanes remarked on when relating their memories of the author, his constant, almost compulsive reading.

“He liked to read in the cinema, even,” Serra told me. “He liked to read in the dark.”

The other common thread in people’s memories of Bolaño was his hair, massive, unruly, and curly, almost hiding his wide glasses.

Serra happily indulged my hunger for personal detail, telling me that Bolaño was a cultural omnivore who loved the films of Aki Kaurismäki and David Lynch, M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense, and Alex Cox’s Sid and Nancy. He had, in fact, briefly enjoyed a protégé relationship with Alejandro Jodorowsky. They fell out over an argument about the Chilean poets Pablo Neruda and Nicanor Parra. He was not particularly invested in sports but he was a FCB fan and watched matches sometimes.

“He was a simple, grounded person,” Serra said.

Bolaño, Serra told me, was allergic to flattery and to attempts to turn him into a celebrity, but he was always friendly to writers who sought him out, and willing to talk to anyone — a description consistent with his appearance in Javier Cercas’s Soldiers of Salamis, in which he has a cameo. Serra remembered the author approaching a police officer and questioning him about the details of his uniform and weapon for what seemed like hours. I wondered how he would have felt about people who came to Blanes in search of not a conversation but a souvenir of Bolaño, like the Catalan couple from Barcelona who came in search of B. in 2008 and had a veritable freakout in front of Videoclub Serra when they realized that they were standing on tiles that Bolaño himself had once stood on.

“I told them I would pry one up and sell it to them,” Serra joked. “I could start a new business.”

As it stands, the CCCB has cornered the market for Bolaño memorabilia. In addition to the exhibition catalogue, in their gift shop one can buy three Bolaño-themed red pins. One simply repeats his name, Bolaño Bolaño Bolaño Bolaño, like a summoning chant. One is printed with a quotation: “Déjenlo todo, nuevamente. Láncense a los caminos” (“Leave everything again. Launch yourself into the streets”). And the final suggests that there is a name for people like me, a proud tribal identification: “Soy bolañista!”

7.

The CCCB exhibit is not for everybody. It’s not, for example, for Sam Carter, author of the New Republic article “The Roberto Bolaño Bubble,” in which Carter argues, “The continued publication and popular packaging of [Bolaño’s] incomplete work may actually be diluting his reputation as a writer of varied talents and fearless ambition.” He concludes, “We have enough.” The totemic value of Bolaño’s mysterious circular charts of his fictional universe would seem a bit overblown, the miniature library of international editions of his books an eye-rollingly obvious conclusion. He would surely quail at the stacks of notebooks that fill the exhibit, ripe for future publication. “There are other South American writers, you know,” he would remind me — as did Ben Ehrenreich at the Los Angeles Public Library’s May 16 roundtable, “The Making of the Great Bolaño; The Man and the Myth,” which featured Ehrenreich, Mexican journalist Mónica Maristain, Barbara Epler, and translator David Shook. Moderated by Héctor Tobar, the event sought to contextualize Bolaño’s posthumous fame. But Maristain — the last journalist to interview Bolaño and the author of a new biography — critiqued Carolina López’s management of his estate, indicating an allegiance to Carmen Pérez de Vega, who was Bolaño’s lover in the last years of his life, and who has vied for public recognition as another widow. This, then, is the kind of press López has assiduously avoided, an understandable decision, especially considering that Bolaño’s daughter Alexandra is not yet 13 years old. For a public library roundtable, the event was deliciously gossipy. Epler explained that the doubt cast on Bolaño’s story of imprisonment in Chile in a 2009 New York Times article (a piece which bizarrely quotes Pérez de Vega but not López) was the result of an American writer’s jealousy of B.’s posthumous success. Epler, ever the diplomat, politely demurred from pursuing an evident difference of opinion with Maristain on López’s decision to switch literary agents. Ehrenreich’s primary contribution was the question: “Who are we not reading because we read Bolaño?”

Cult writers attract as many detractors as they do devotees. Carter and Ehrenreich aren’t alone in their Bolaño fatigue. Many people I know, most of them fellow fiction writers, share it. I don’t blame them. It’s hard not to be aggravated when the gatekeepers of American letters won’t give an unsolicited submission a second glance but will make a dead man their new books editor, as Harper’s did in 2006. For people who feel that we have enough Bolaño, the three pairs of glasses at the end of “Bolaño Archive. 1977–2003” do not possess a curious melancholy power. These people are not drawn to the end of the exhibit and held perfectly still by the way he saw the world.

After “Bolaño Archive. 1977–2003,” I returned to Blanes to visit Narcís Serra and Cristina Fernández Recasens. The city was lovelier than ever in the pale violet light of spring. Cristina and I sat at a café, talking about the resilience of our connection to Bolaño, the immutable and inexplicable bond that had developed between us because we loved his books. She pointed to a statue of the Virgin, perhaps eight inches tall, installed in a high sconce in an old wall across the square.

“It says that if you blow her a kiss, you get a year of forgiveness,” she told me. The Virgin wore a blue cloak and an expression of tired beneficence. “I don’t know what it is,” she said, “why exactly Bolaño’s work brings people together. It has this power. He makes writers feel invincible. Brave.”

I thought of a line from B.’s “Caracas Address,” a kind of writerly rallying cry: “Literature is basically a dangerous undertaking.” It appealed to my ego, of course, but there was something else underneath it, a palpable tenderness, crystallized now in the streets of Blanes, in the taste of coffee and the smell of the sea.

“Do you stop and think about the fact that you are now friends with the friends of Bolaño?” my husband asked me, when I called him that night. That’s what it is, I think: not the glamour of celebrity, the thing B. so hated, but the simple miracle of friendship. That was what I was after, what I felt almost guilty about: the friendship I found in B.’s books, and now, in his town.

Cristina and I finished our drinks. She had a dance class to get to. We blew the Virgin kisses, and I went, again, into the streets.

“Bolaño Archive. 1977–2003” runs through June 30 at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona.

The author wishes to thank the Del Amo Foundation, the Serra Family, Cristina Fernández Recasens, Jaume Pujadas, Theis Duelund Jensen, and her family for their support and assistance with this essay.

¤

Shares