By striking down Section 4 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and thereby gutting the act’s Section 5, the Supreme Court has presented defenders of voting rights in America with a challenge —and a historic opportunity. The challenge is the need to avert a new wave of state and local laws restricting voting rights in the aftermath of the Court’s decision. The opportunity is the chance that Congress now has to universalize Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act, to make it apply to all 50 states.

Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 imposed a special coverage formula on jurisdictions with particularly bad histories of racial discrimination in voting, including nine states—Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas and Virginia—and dozens of county and municipal governments, including the Bronx, Brooklyn and Manhattan. Section 5 authorized the Justice Department to require “pre-clearance” of proposed changes in electoral laws in these jurisdictions. The pre-clearance requirement has been used in recent years to thwart attempts by the ethnocentric non-Hispanic White Right to engage in voter ID laws or redistricting plans that were evidently motivated by the desire to indirectly eliminate or dilute the votes of nonwhite citizens or poor citizens.

By striking down Section 4, the coverage formula, the Court gutted Section 5, the authorization of pre-clearance. Eliminating pre-clearance gives states whose legislatures are controlled by the bitter, desperate, demographically declining White Right a green light to try to enact voter restriction policies that are racially discriminatory in their effect and undoubtedly in their intent.

Is there anything that progressives, centrists and enlightened conservatives can do, to avert a new wave of voter restrictions at the state level, which, while racially neutral in appearance, have the intent and effect of reducing black and Latino electoral power, to the benefit of the ethnocentric White Right?

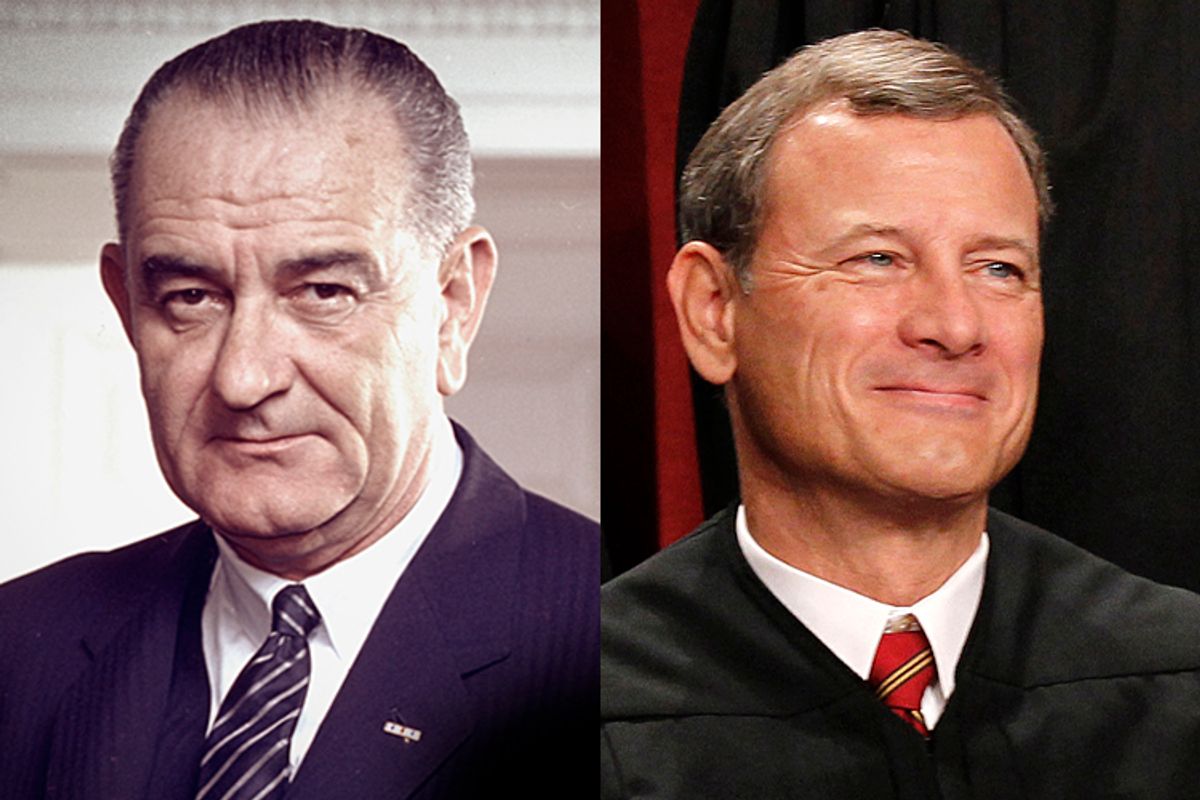

If I read the majority opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts correctly, Congress could enact a version of Section 4 that could be approved even by this mostly reactionary Supreme Court. Roberts criticized the recent reauthorization of the VRA for not updating it:

Congress did not use the record it compiled to shape a coverage formula grounded in current conditions. It instead re-enacted a formula based on 40-year-old facts having no logical relationship to the present day.

Congress should accept the Court’s challenge and rewrite the Voting Rights Act to revive Section 5 pre-clearance by enacting a version of Section 4 that passes this Court’s newly announced test.

The option of trying to revive a modified version of the old Section 4 would probably fail. For one thing, it is not clear how any modified list of states, short of the whole, could satisfy this Supreme Court, with its solicitude for “state sovereignty” (a concept more at home in the Confederate Constitution than in the U.S. Constitution).

Another problem is that even progressive Democrats might shy away from a vote that stamped the label “racist” on Alaska or Texas, as opposed to, say, California or Wisconsin. In the past, most recently in 2006, members of Congress avoided gratuitously insulting nine states — and several New York City boroughs! — by voting to renew all or part of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Any new legislation that sought to name particular states as particularly racist would undoubtedly die in Congress.

Fortunately, there is an alternative: Congress can rewrite Section 4 to make it apply to all 50 states in perpetuity, thereby reviving — and universalizing — Section 5’s federal pre-clearance of state and local electoral law changes.

The rationale for universal federal pre-clearance of changes in state and local electoral laws is independent of the legacy of anti-black racism in the U.S. as a whole and the South in particular. In any ethnically diverse democracy that is also a federal system, the national government needs to be able to restrain the power of ethnic groups, including those that are national minorities but local majorities, from manipulating the electoral laws in sub-national jurisdictions to create tyrannical “ethnocracies” like the older White South.

Today, non-Hispanic whites are a minority in California, Texas and other states. By the middle of the 21st century, non-Hispanic whites will be a minority in the U.S. population as a whole, according to some projections. Who knows? Maybe in the future the outnumbered non-Hispanic white group, or other minority communities, will need to be protected against unjust attempts to dilute their votes by new, post-white majorities that prove to be as ethnocentric and undemocratic as non-Hispanic whites frequently were when they enjoyed majority status.

In other words, the rationale for congressionally authorized federal pre-clearance of changes in electoral systems at the state and local level would be compelling, even if there had never been any history of racism in the U.S. at all. The mere prospect of potential state and local majority tyranny in the electoral arena is rationale enough for a universal, permanent pre-clearance policy by the federal government.

It might be objected that this policy would not prevent similar majority tyranny at the federal level. That is true, but it is not a persuasive argument against federal pre-clearance. For most of American history, the greatest threats to enfranchisement of various minorities have been at the state and local level. The few exceptions — for example, Northern states that refused to enforce the federal fugitive slave act — merely underline the rule.

The federal government repeatedly has been forced to use not only the law but also military force to restrain local majority tyranny, during the Civil War and Reconstruction and again during the civil rights revolution. Conversely, state and local majority tyranny have flourished only when tolerated by the national majority. In the United States, the national majority has always been, and likely always will be, a more reliable champion of civil rights and voting rights than local majorities.

Universalizing Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act, then, makes excellent sense on its merits. It would make for smart politics, too. Proposing to universalize Section 4 would be a no-lose proposition for progressives, centrists and non-racist conservatives.

If a law universalizing Section 4 were enacted, then the Northern and Western states would have nothing to fear — unless, of course, their state governments were trying to use devious methods to restrict or dilute the voting power of particular groups, like the disproportionately minority poor. But that is as it should be. Why should race-motivated voter ID laws or redistricting schemes to dilute minority voters by “packing” them in ghettoized electoral districts be subject to more federal scrutiny in the South than in the Midwest or West Coast or New England? The same level of federal scrutiny should be brought to bear everywhere in the United States.

If a law universalizing Section 4 were to die in Congress, it would almost certainly be killed by Republicans based in the former Confederacy. Their success in stopping universalization of Section 4 would be a Pyrrhic victory, further identifying the Republican Party in the national mind with the most benighted white reactionaries in the former homeland of slavery and segregation. This outcome would strengthen not only Democrats but also reformist Republicans making the case that their party must be freed from its Southern captivity.

The neo-Confederate opponents of such a proposed law could not complain that it imposed a double standard. After all, the new, universal Section 4, along with the revived pre-clearance system of Section 5, would apply to Massachusetts, New York and California, as well as to Texas, Mississippi and Alabama.

Would a universalized version of Section 4 be acceptable to this Supreme Court? Because all states would be treated equally, the argument that it treated some unfairly would be irrelevant. Opponents would have to argue that by permanently universalizing Sections 4 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act, Congress was exceeding its constitutional authority. That would be a hard argument to make, given the clear language of the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1870:

Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Section 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

If universal, perpetual federal pre-clearance of changes in electoral laws by all state and local governments, to make sure they do not disadvantage particular minorities, is not “appropriate legislation” for defending “the right of citizens of the United States to vote” under the 15th Amendment, it is hard to imagine what “appropriate legislation” would be.

Justice Roberts has stated that Congress can pass a new version of the Voting Rights Act that reflects “current conditions.” Congress should take him up on his offer and rewrite the Voting Rights Act to make it apply to all 50 states and all local governments, forever.

Shares