On Oct. 29, 1948, the Soviet Union suddenly changed all its ciphers and codes. What later became known as "Black Friday" delivered a huge shock to the two U.S. intelligence agencies that had conducted the bulk of American code-breaking efforts during World War II and its immediate aftermath. Before Black Friday, the Army's SIS and the Navy's OP-20-G complacently assumed that they had acquired the keys to most of the world's encrypted communications. But with a flip of the switch the U.S. was once again in the dark -- just as the Cold War was heating up.

"One of the gravest crises in the history of American cryptanalysis," writes historian Colin Burke, led directly to the 1949 mergingof the SIS and OP-20-G into the Armed Forces Security Agency. Three years later, another bureaucratic shuffle transformed the AFSA into the National Security Agency. A sense of panic induced by the "Soviets' A-Bomb, the Berlin Blockade, the forming of the satellite bloc in Eastern Europe, the fall of China, and the Korean War" -- all of which "were not predicted" by the intelligence agencies -- encouraged the U.S. government to authorize the NSA to spend tens of millions of dollars on computer research, in the hope that technological advances would help crack the new Soviet codes.

Colin Burke is the author of "It Wasn't All Magic: The Early Struggle to Automate Cryptanalysis, 1930s-1960s." Burke completed his history in 1994, but until last week, his volume of crypto-geekery had only a handful of readers. Part of a series produced by the NSA's Center for Cryptological History, "It Wasn't All Magic" was considered classified material until May 2013, and was only made available online on June 24.

Nice timing! With the NSA currently occupying its highest public profile in living memory, a look back at its early history is quite instructive. It is useful to be reminded that the mandate to spy and surveil and break codes was absolutely critical to the early growth and evolution of computer technology. Some things never change: The immense effort required to crack German and Japanese codes during World War II are an early example of the intimidating challenges posed by what we now call "big data."

"Incredible amounts of calculation were needed for pure cryptanalysis," writes Burke. Meeting the need for that calculation led to the NSA and its predecessors becoming key players in unleashing the digital age; and, ironically, creating the conditions that have made so much of our modern lives surveillable by the NSA. A direct line connects our Twitter-obsessed, Snapchat-crazed lives with the exploits of the codebreakers 60 and 70 years ago.

Few people in 1948 might have been able to imagine a future when the NSA would be employing its massive computing capabilities to gather and process information on all Americans, but that is exactly what the NSA was born to do: make sense of the proliferating information age.

* * *

1948's Black Friday was hardly the first time that an inability to make sense out of big data sent shock waves through the United States' intelligence apparatus. Before World War II, it was clear to U.S. military code-breakers that they could not keep up with information overload.

"The development of new cipher machines and the maturation of radio led to a critical data problem for America's cryptanalysts," writes Burke. "There was more and more data, and it was overwhelming those who were charged with turning it into useful information for policymakers. The failure to predict the attack on Pearl Harbor, for example, was the result of too much data. The thousands of intercepted Japanese naval messages could not be analyzed with the men and equipment available to ... OP-20-G."

Burke also references a fascinating story about a typhoon in December 1944 that swept over a naval task force led by Adm. Halsey and resulted in the loss of 800 American lives. The disaster might have been avoided, writes Burke, if the Navy had been able to efficiently process "the combined weather report" produced by Japanese weather stations. At that late stage in the Pacific conflict, the American fleet was moving faster than it could set up its own weather stations. But, again, there was just too much data for intelligence services to keep up with their clumsy pre-digital technologies.

And even World War II's exigencies paled before what the NSA faced in the early '50s. The problems went beyond the brute force necessary for code-breaking. Just keeping up with data gathered in the clear proved near impossible.

By 1955 there was a torrent of "noninformation" flowing into NSA. The United States had more than 2,000 round-the-clock listening positions that were sending thirty-seven TONS of intercept material to NSA each month. In addition, some 30,000,000 words of intercept were sent by teletype. The data overload grew with every year and every Soviet challenge. NSA's posts were intercepting 2,000,000 messages a month from just one Soviet system, and the vast majority of that was plain text ... Within a short time, punching 1,000,000 IBM cards a month for just one problem was common.

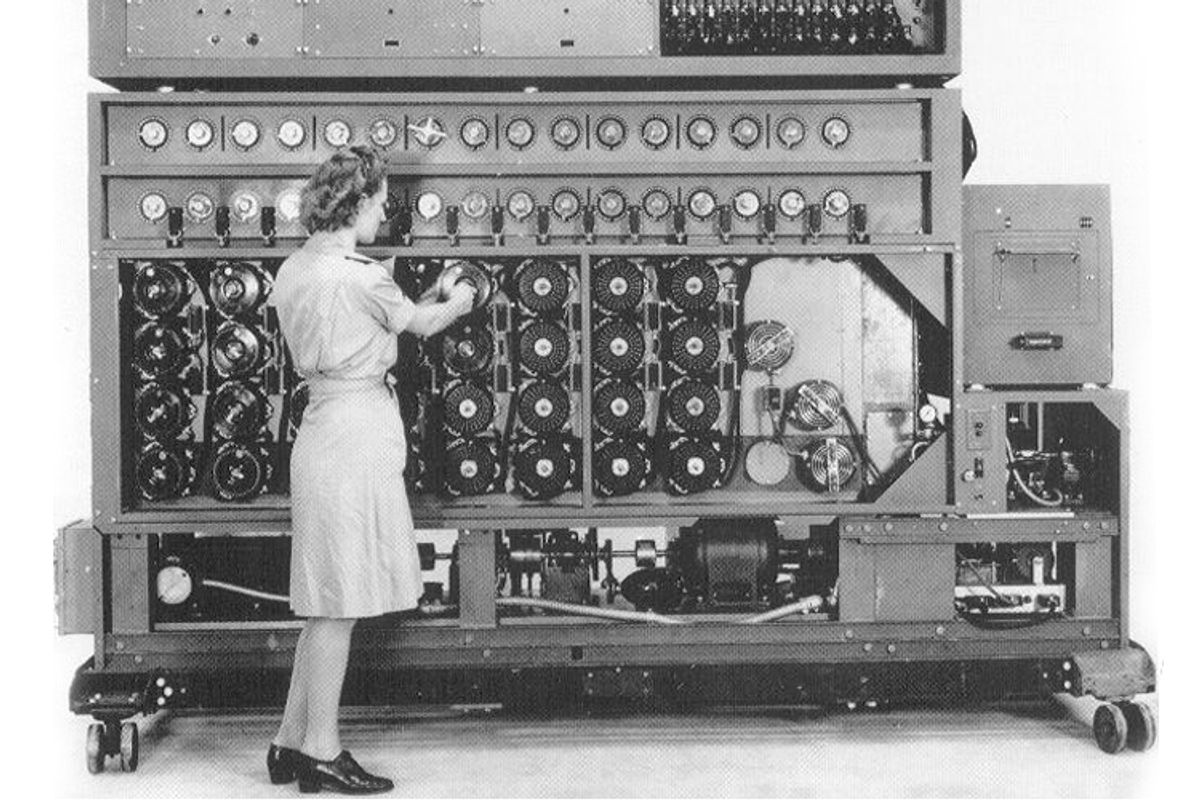

Decades before software solutions like Hadoop were developed, big data required big iron. But there was no commercial market for untested general-purpose computers with price tags of a million dollars and up. From the late 1930s on, the NSA and its predecessors were forced to experiment with a wide variety of cumbersome technologies, and push established companies like IBM to design new machines aimed to realize government priorities.

"NSA's ... computer purchases and its research and development contracts helped establish America as the world's leading computer manufacturer," writes Burke. "From the moment of its creation, it was at the cutting edge of computer technology and architecture ... Based on an intense faith that new machines would work cryptanalytic and data processing miracles, NSA became involved in many projects to create new generations of computer technology."

Most of "It Wasn't All Magic" is a fairly dry, jargon-packed recitation of experiments in computer technology that sounds to modern ears as if it was written in Etruscan. Only in computer history does the archaeology of 50 years ago seem as distant as Sumer. Ironically, despite the claims made for NSA's long-term influence, a fairly common theme of the narrative is one of failure. For almost the entire period that Burke examines, the NSA and SIS and OP-20-G geeks were unable to realize the full extent of their dreams. Practical exigencies and theory did not match up.

But the pressure and funding steered toward the private sector unquestionably provided a powerful incentive for technological progress. The history of the computer industry offers as strong an argument for the importance of government investment in pushing forward the development of new technology as can be found in the entire domain of industrial policy. The free market, left to itself, would have required decades longer to make the same advances. There simply wasn't any money to be made cracking Soviet ciphers.

If it hadn't been for the Cold War, it's difficult to imagine what our digital lives might be like today. When World War II ended, writes Burker, there was a brief moment in time when the pressure to attack big data seemed to relax.

For contemporaries, the future was uncertain. No one imagined that America was going to build a multi-billion dollar intelligence bureaucracy that seemed to have a life of its own. In fact, for those in the cryptanalytic organizations in early 1945, there were signs they might return to the isolated and have-not world of the 1930s, an era when American politicians condemned "reading other gentlemen's mail."

Unfortunately, Burke's tale of "one of the great techno-gambles in American history," reaches no closure in "It Wasn't All Magic." The narrative ends, rather abruptly, around 1960. We are teased with the declaration that by "the early 1960s, NSA's 'basement' became one of the world's great computer data processing centers," but we don't get any hints about what was accomplished in that basement. And considering the fact that there are sections of Burke's book concerning events as far back as the late 1940s that are still redacted for security reasons, one assumes that the later we get in time, the less we will be able to find about about what the NSA was up to, during the 1960s and beyond.

But this much we do know. The early 1950s, writes Burke, are now considered "the Dark Ages of American Cryptanalysis." We can guess, thanks to the efforts of Edward Snowden, that "dark ages" isn't the operative description for what we're living through now.

Shares