The Brave New World is officially here — and it’s not just new, it’s also expensive and, at best, unproven.

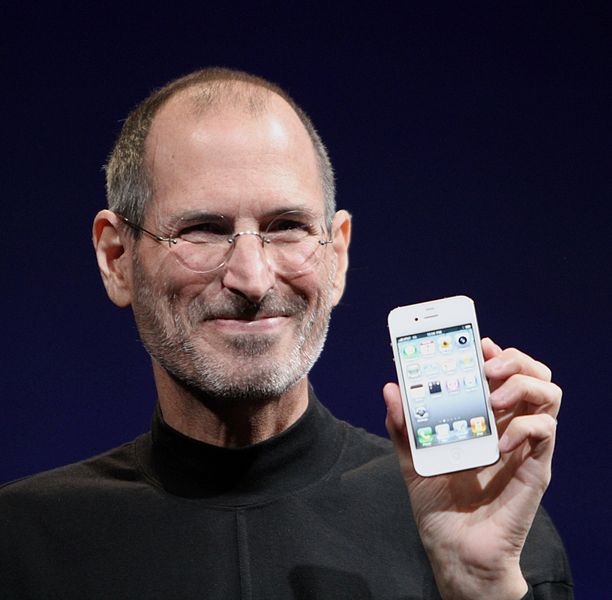

That’s the news of the last few weeks in the world of education. In Europe, there is the launch of “Steve Jobs schools” where, according to Der Spiegel, “the entire education experience (is) offered via tablet computer” and where “there will be no blackboards, chalk or classrooms, homeroom teachers, formal classes, lesson plans, seating charts, pens, teachers teaching from the front of the room, schedules, parent-teacher meetings, grades, recess bells, fixed school days and school vacations.” In these Apple utopias, if “a child would rather play on his or her iPad instead of learning, it’ll be okay.”

Back here at home, a similar transformation is happening — albeit at a slower pace — in school districts that are spending big money to give iPads to every student. Indeed, following smaller districts from across the country, the Los Angeles Unified School District — the second largest in the nation — just generated big headlines by becoming one of the 600 districts handing over public money to Apple in exchange for iPads.

How much money, you ask? In Los Angeles, many millions of dollars. If that sounds a bit vague, that’s because it is, thanks to the hard-to-estimate total costs of all the variables in technologizing schools. In L.A., for instance, school officials approved an initial $50 million in bonds (read: public debt) to finance the first stage of its iPad-for-every-student program. However, according to the Los Angeles Daily News, those officials quietly acknowledge that the plan will cost a whopping half-billion dollars when fully implemented.

Such massive expenses are, to say the least, alarming — especially in school districts that are simultaneously ramping up their spending on technology and slashing funding for traditional education investments like teachers and infrastructure.

Los Angeles, again, is a good example; the same school district that is going to spend a half-billion dollars on iPads has been laying off teachers. To justify those layoffs, the school districts have been citing a $543 million district budget shortfall, yet somehow, those same officials apparently don’t cite that same budget shortfall as a reason to avoid spending $500 million on iPads. Why? Because education technology triumphalists typically portray iPads as long-term cost cutters for school districts.

As the New York Times sums up that argument, these triumphalists believe iPads and attendant iBooks will “save money in the long run by reducing printing and textbook costs.” The enticing idea is that schools may have to invest huge money upfront, but they will supposedly see huge savings in out years.

The trouble is that there is little evidence to suggest that’s true, and plenty of evidence to suggest the opposite is the case.

As respected education consultant Lee Wilson notes in a report breaking down school expenses, “It will cost a school 552% more to implement iPad textbooks than it does to deploy books.” He notes that while “Apple’s messaging is the idea that at $14.99 an iText is significantly less expensive than a $60 textbook,” the fact remains that “when a school buys a $60 textbook today they use it for an average of 5-7 years (while) an Apple iText it costs them $14.99 per student – per year.” As Lee notes, that translates into iBooks that are 34 percent more expensive than their paper counterparts — and that’s on top of the higher-than-the-retail-store price school districts are paying for iPads.

As I pointed out in a newspaper column last year:

Those (inflated) costs might be justifiable when a new device is a sure bet to improve education. But a school’s wager on computer technology as a pedagogic panacea is often just that: a blind gamble, and one that evidence shows is hardly safe.

Here in Colorado, for instance, the non-profit I-News Network recently reported that students attending the state’s “full-time online education programs have typically lagged their peers on virtually every academic indicator, from state test scores to student growth measures to high school graduation rates.” Stanford University researchers found similar results in their separate study of online schools in Pennsylvania.

And after its exhaustive national investigation of the trend, The New York Times concluded that “schools are spending billions on technology, even as they cut budgets and lay off teachers, with little proof that this approach is improving basic learning.”

Now, sure, it is true, there has been some anecdotal evidence suggesting that iPads can help students in their learning. But there are three problems with such evidence.

First and foremost, it is generated in a vacuum. Certainly, iPads in certain conditions may modestly help — or at least not hurt — kids in their educational endeavors. But the biggest question for schools should be a comparative one: namely, is it better to spend education dollars on iPads rather than on something else? In the age of finite resources, this is an especially relevant query when the “something else” could be more teachers and smaller class sizes — that is, an investment that has far more proven education results than iPads. In light of that, it is hard to argue that a massive investment in iPads is more prudent than putting the money into other education options available.

Second, for all the anecdotal evidence supporting iPads, there’s other anecdotal evidence from schools that suggests iPads actually harm education.

Finally, there’s the fact that anecdotal evidence is just that — anecdotal. As Stanford’s Larry Cuban points out, there is no comprehensive scientific “body of evidence that iPads will increase math and reading scores on state standardized tests” nor that “students using iPads (or laptops or desktop computers) will get decent paying jobs after graduation.” And, incredibly, Los Angeles school officials spending the money on the iPads have made clear that, according to Cuban, they will collect “no hard data on how often the devices were used, in what situations, and under what conditions.” In other words, the investment is based on blind faith.

Why would schools go forward on such blind faith, you ask? Part of it is the allure of silver bullet, and part of it has to do with cold, hard cash.

In terms of the former, Cuban explained it to Pulitzer Prize-winner Peg Tyre:

“First, the promoters’ exhilaration splashes over decision makers as they purchase and deploy equipment in schools and classrooms,” said Larry Cuban, professor emeritus of education at Stanford University and author of Oversold and Underused: Computers in the Classroom in an email to me. “Then academics conduct studies to determine the effectiveness of the innovation [and find that it is] just as good as—seldom superior to—conventional instruction in conveying information and teaching skills. They also find that classroom use is less than expected…Such studies often unleash stinging rebukes of administrators and teachers for spending scarce dollars on expensive machinery that fails to display superiority over existing techniques of instruction and, even worse, is only occasionally used.”

The promoters Cuban refers to, of course, come to school boards with money — lots of it. As both Tyre and the Wall Street Journal note, venture capital is pouring into the education technology sector. Basically, investors see the potential for big profits from convincing school districts to replace proven education methods with unproven technology products.

Not surprisingly, some of those profits finance armies of lobbyist and salespeople to harass schools’ technology directors to support new technology procurement (one such technology director told the New York Times he now gets “one pitch an hour”).

Some of the profits also become campaign contributions to school board members who set general procurement policy. A good example of the latter is Los Angeles, where, as NPR reported, a division of Rupert Murdoch’s empire “gave $250,000 toward a group that helped to fund like-minded candidates running for school board.” Murdoch, of course, is investing heavily in an education technology business that aims to get tablets into schools.

Reviewing all of this, of course, isn’t to make some sort of Luddite argument against technology in general. It is only to make the point I made last year about verification. To reiterate that point once again: Yes, technology can be a great tool for education, but huge amounts of public money shouldn’t be dumped into technology investments without data proving those investments are worth it. That’s especially the case at a time when money is being cut from things that have proven to boost academic achievement.

Such a truism should be obvious, self-evident and hardly controversial. Indeed, it is only controversial to those companies and politicians with a vested financial interest in promoting education technology triumphalism, regardless of how factually unsubstantiated such triumphalism remains.