My parents had gotten their views about African Americans and the civil rights movement from Robert Welch, an old Southern boy [and co-founder of the John Birch Society]. He’d always thought the Negroes had it good in the United States, a view he explained in a pamphlet published in the early 1960s, Two Revolutions at Once.

In it, Welch claimed that “educational opportunities [for Negroes] have tremendously improved” with “some states [in the South] spending as much as fifty percent of their total school budget on Negro schools, while deriving only fifteen percent ... from taxes paid by the Negro population.” He claimed that job opportunities for the Negro had “markedly increased despite a determined undercover effort by the Communists to prevent this trend.” This assertion was unproven, but that didn’t stop Welch from repeating it. Welch even believed that “separate but equal” had been “gaining substance in the matter of equality and losing rigidity in the matter of separateness.”

In 1963, Welch was still insisting that “separate but equal” was “surely but slowly breaking down, with regard to public facilities, wherever Negroes earned the right by sanitation, education, and a sense of responsibility, to share such facilities.”

As jarring as these words are today, they worked well for the John Birch Society in the 1960s — so well that, by 1965, JBS could boast more than one hundred chapters in Birmingham, Alabama, and its surrounding suburbs. The New York Times reported that “the society is capitalizing on white supremacy sentiment, as well as on a general social, religious and political conservatism in the south.”

As a Birch kid, I wasn’t a bit surprised. The JBS had been fighting the civil rights movement since its founding, and the events of 1962 and 1963 added even more grist to their racist mill.

* * *

In the fall of 1962, chaos erupted in Mississippi when the federal courts ordered the admission of James Meredith, a twenty-nine-year-old Air Force veteran, to the University of Mississippi. The Ole Miss Rebels and segregationists across the former Confederacy were not about to sit quietly by while a “colored” man soiled the 144-year whites-only history of the university. Ross Barnett, Mississippi’s governor, didn’t help matters when he vowed that “no school in our state will be integrated while I am your Governor.”

President Kennedy sent sixteen thousand federal troops to quell the rioting in Oxford. One of the protestors was General Edwin Walker, John Bircher, friend of my parents, and right-wing hero. Walker had resigned from the Army almost a year earlier. In no time, he took up the cause he called “constitutional conservatism.” In speeches across the country, Walker denounced the Kennedy administration’s “no-win” foreign policy toward the “world Communist conspiracy.”

Walker’s accusations alarmed members of the Special Senate Preparedness Subcommittee, which had called him to testify. In April, giving his Senate testimony, the general challenged the loyalty of then secretary of state Dean Rusk and of Walt W. Rostow, head of policy planning at State. When questioned about calling these men Communists, Walker said, “I reserve the right to call them something worse such as traitors to the American system of constitutional government, national and state sovereignty and independence.” A small melee occurred after the hearing when the general punched a reporter trying to ask a question.

Following the hearing, Walker became “the flag-bearer for the entire conservative movement,” according to Jonathan Schoenwald. In our house, he was simply “The General.” Just a few months later, Walker was in the thick of the troubles in Mississippi. He even called for Americans from every state to march to Mississippi and help Governor Barnett keep James Meredith out of Ole Miss.

The situation in Oxford rapidly deteriorated, leading to two deaths and over two hundred injuries. According to Time, about two hundred were arrested, including General Edwin Walker. During the melee, Walker proclaimed that court orders allowing integration were part of “the conspiracy of the crucifixion by Antichrist conspirators of the Supreme Court.” One man close to Walker said, “There was a wild, dazed look in his eyes.”

My father said, “The General spoke the truth, and they made him crazy."

Following the Oxford situation, which the JBS labeled the “Invasion of Mississippi,” Robert Welch said, “We are now reaching the point in the Communist timetable where it is necessary for the Central Government in the United States to demonstrate ... how dangerous and futile it will be for the people anywhere, or their local governments, to resist that central power.”

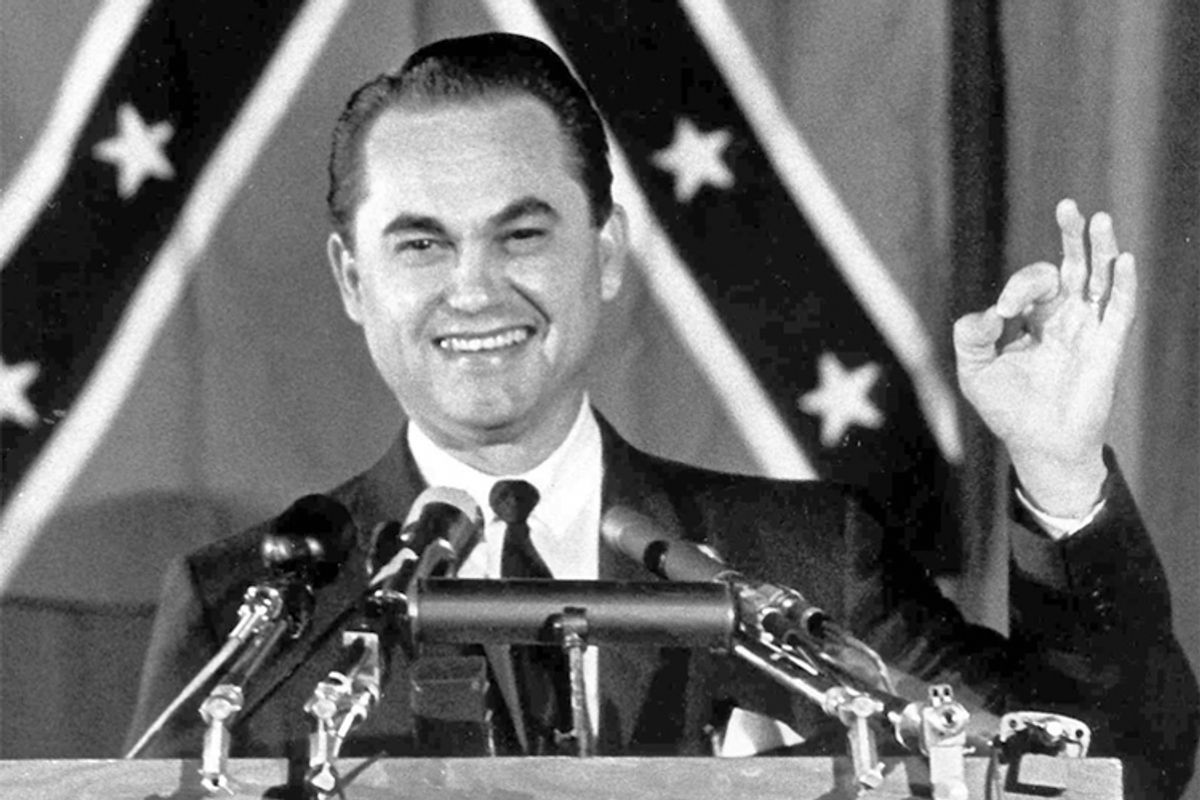

In January of 1963, my parents found themselves a new hero — the newly elected governor of Alabama, George Wallace. He won them over after declaring, in his inaugural address, “I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Wallace went on to threaten a “Dixiecrat rebellion,” Time reported. “We intend to carry our fight for freedom across the nation ... We, not the insipid bloc of voters in some sections, will determine in the next election who shall sit in the White House.”

“George Wallace is a true statesman,” my father said.

“We have to stand with the governor now or it’ll be Chicago,” Mother added.

Five months later, I pulled the latest Life magazine from the stack of mail and headed upstairs. My parents condemned Life as a left-wing piece of crap, though like millions of Americans they subscribed. I didn’t care about the politics; I loved the photos. That week, Nelson Rockefeller and his new wife, Happy, graced the cover.

My parents loathed Rockefeller for his liberalness and for his divorce and quickie wedding. “He’s disgusting, and she’s a harlot,” my mother said of the couple.

“Rockefeller’s a Commie, period,” Dad said.

“Who cares?” I thought as I daydreamed through the magazine, skimming the stories and the ads. When I came to page twenty-five, I woke up.

In a grainy, black-and-white, uncaptioned photo, three civil rights protestors braced themselves against a building. Their soaking wet clothes hugged their bodies. One man appeared to be shielding the woman next to him from the fire hoses that had been turned on them. In other shots, police dogs tore the clothes off young boys as they tried to run away. “Bull” Connor, the Birmingham police commissioner, described the scene saying, “I want ’em to see the dogs work. Look at those niggers run.”

I fell back on my bed and covered my eyes. “This cannot be happening in my country,” I told myself. I knew my parents and the JBS would be totally supportive of Bull Connor and his methods. I also knew that there was nothing I could say to change their minds. The best thing for me was to shut up and earn enough money to go to Dallas.

Shortly after the Birmingham riots, Governor Wallace refused to comply with federal orders to integrate the University of Alabama. The situation escalated until President Kennedy called out the National Guard and forced the governor to stand down. The schools in Alabama were eventually integrated, but not before Wallace had emerged as an icon for racists and rightwing extremists everywhere.

As African Americans continued to ride, sit in, and march for their civil rights, the JBS ramped up its rhetoric around the movement. Welch reminded all members that the whole idea of civil rights was conceived by the Communists to “foment racial riots in the South.” The goal, Welch insisted, was “to break off one part of the United States after another until they [the Communists] have converted it into four separate Communist police states.” All of this would be made possible by “brutal, ambitious and heavily armed Negroes operating in guerrilla bands, perpetrating vicious atrocities on their fellow Negroes.” And, lest the white folks relax, Welch continued, “These guerilla bands will be murdering the whites, too.”

Thanks to Welch, my parents were terrified. So was I, but my fear was for the safety of the protesters who wanted nothing more than the same rights white Americans had.

Late in August of 1963, while my parents were on their annual summer vacation in Gloucester, Massachusetts, I carted a drink, a peanut-butter sandwich, and the Chicago Tribune to our basement rec room. I scanned the front page and noticed a column about a protest march in Washington to be held that day.

Curious, I snapped on the TV and switched the channel to CBS. It took some time to adjust the rabbit ears, but gradually I got the picture focused. On the screen, thousands of people stood shoulder-to-shoulder in front of the Lincoln Memorial. The crowd was so enormous that it spilled along both sides of the Reflecting Pool and stretched nearly to the Washington Monument. I’d never seen anything like it.

It was August 28, 1963. The March on Washington was underway.

I watched as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stepped to the podium. I’d heard a lot about Dr. King. I’d heard he believed in a Negro country inside the United States. I heard he encouraged violence against whites. I’d heard he hired thugs to terrorize black folks who disagreed with him. I’d heard he was as bad as they came.

But until that day, I’d never actually heard him.

From his first words, I was riveted. When he talked about the “fierce urgency of now” and “meeting physical force with soul force,” about his “dream rooted in the American dream,” that “sons of former slaves and sons of former slave owners will sit at the table of brotherhood,” that children would “not be judged on the color of their skin but the content of their character,” and “little black boys and little black girls will join hands with white boys and white girls as brothers and sisters,” chills ran up my arms. When the throng burst into “We Shall Overcome,” I stood in my basement, all alone, and sang with them: “We shall overcome some day.”

I touched my face. It was damp. Until that moment, I hadn’t realized I was crying.

Excerpted from "Wrapped in the Flag: A Personal History of America’s Radical Right" by Claire Conner (2013, Beacon Press). Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.

Shares