In the same week that saw a heartbreaking New York Times Op-Ed published by the grandfather of a 16-year-old American boy extrajudicially executed by one of President Obama's drone strikes, one of the Obama administration's highest-ranking officials delivered a powerful speech decrying the government policies of preemptive aggression behind such strikes, saying:

Separate and apart from the case that has drawn the nation’s attention, it's time to question laws that senselessly expand the concept of self-defense and sow dangerous conflict...

There has always been a legal defense for using deadly force if -- and the "if" is important -- if no safe retreat is available...we must examine laws that take this further by eliminating the common-sense and age-old requirement that people who feel threatened have a duty to retreat...

By allowing and perhaps encouraging violent situations to escalate in public, such laws undermine public safety...the list of resulting tragedies is long and, unfortunately, has victimized too many who are innocent. It is our collective obligation (to) ensure that our laws reduce violence, and take a hard look at laws that contribute to more violence than they prevent...

...We must also seek a dialogue on attitudes about violence and disparities that are too commonly swept under the rug...and by paying tribute to the young man who lost his life...and so many others whose futures have been cut short in other incidents...And we must do so by engaging with one another in a way that is at once peaceful, inclusive, respectful and strong.

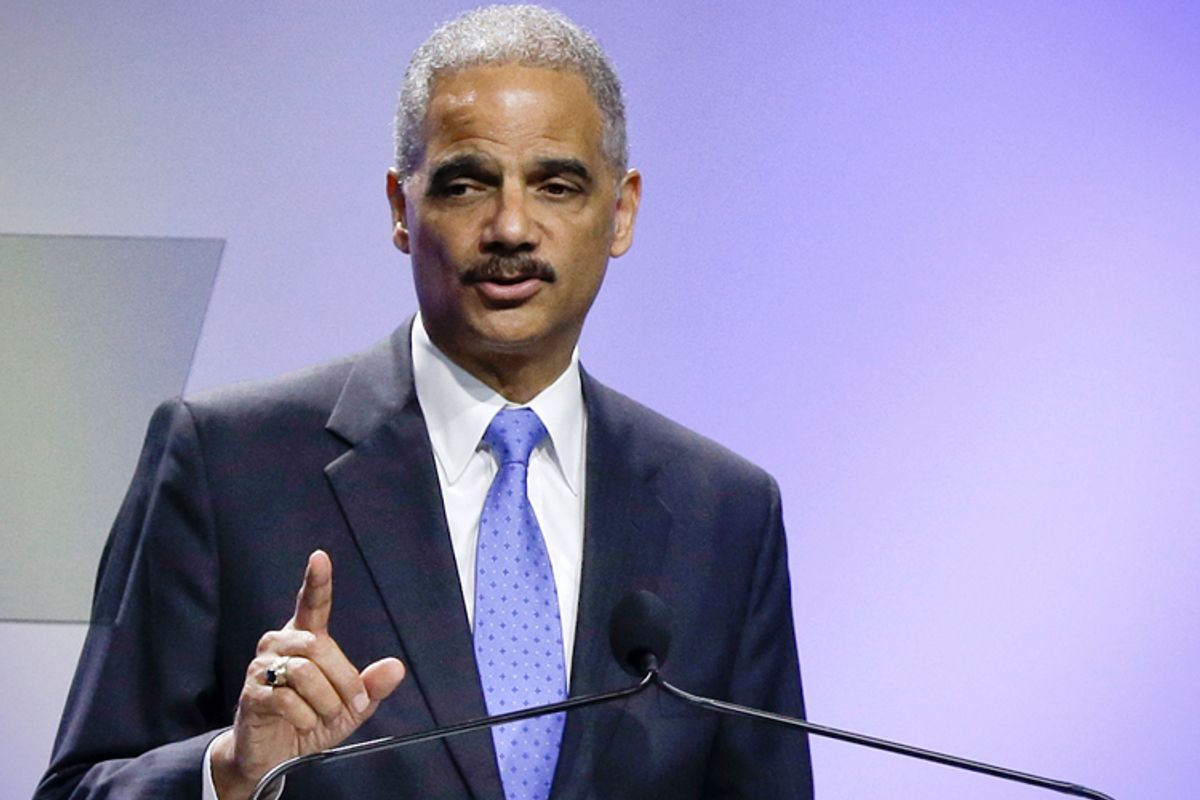

The Op-Ed and the underlying crime referenced in the opening paragraph of this article are all too real, as is the above word-for-word excerpt of this week's speech by Attorney General Eric Holder to the NAACP.

What isn't true in the first paragraph of this article is the assertion that the speech was about the abhorrent policies and ideology behind President Obama's drone strikes -- one of which killed a 16-year-old American child of color named Abdulrahman al-Awlaki (and others that have killed hundreds, if not thousands, of other civilians). It was actually about the also abhorrent policies and ideology that created an environment for George Zimmerman's also unacceptable execution of a 17-year-old American child of color named Trayvon Martin. In fact, in that speech, Holder did not amend or rescind his earlier declaration that killing the 16-year Awlaki was "consistent with (the American people's) values and their laws" -- in fact, he didn't mention the 16-year-old boy at all.

Why not?

With Nasser al-Awlaki's New York Times Op-Ed today headlined "The Drone That Killed My Grandson," and with his upcoming court battle against the Obama administration, this is one of the most high-profile and important moral and legal questions facing the country, because it implicitly asks whether we are willing to simply accept institutional vigilantism -- the kind aimed at people based on their racial, ethnic, religious and geographic profile.

Of course, a different form of vigilantism -- individual vigilantism -- was a central component in Zimmerman's murder of Martin. The killer presented himself as an archetypal vigilante: a self-appointed neighborhood watchman who chased -- and then gunned down -- Martin because, as he told non-emergency dispatchers, he presupposed that Martin was "up to no good." In this case, the individual vigilante unilaterally declared himself above laws against harassment and murder, hunting down a kid likely because he deemed that kid inherently suspicious based on the kid's racial profile.

Horrifyingly, the Sanford court effectively ruled that this kind of individual vigilantism is not a crime. And that ruling has rightly generated outcry from those who in general oppose such individual vigilantism and in specific oppose such individual vigilantism disproportionately aimed at people of color.

But as grotesque as it is, and as right as Holder is to decry it, individual vigilantism is no more objectionable than the institutionalized vigilantism actively promoted by Holder and the Obama administration (and, as Falguni Sheth notes, cheered on by many liberals who criticize Zimmerman).

Institutional vigilantism is the kind of lawless behavior whereby the government extrajudicially executes a 16-year-old boy and -- separately -- his father, without citing a legal rationale or even so much as charging either of them with a single crime.

It is the kind of lawless vigilantism that denies a grandfather legal standing when he deigns to ask the government to at least explain why it incinerated his grandson.

It is the kind of vigilantism that, as NBC News shows, targets people for death based not on their identity, but on their profile.

And yes, it is the kind of drone-war vigilantism that, as the Atlantic's Ta-Nehisi Coates notes, "shares an ugly synergy with the broad-swath logic employed (by) the killer of Trayvon Martin." Indeed, the New York Times points out that the administration justifies the drone killing of civilians on explicitly Zimmmerman-ish grounds, insisting that regardless of innocence, those extrajudicially executed by the government deserve their punishment because by virtue of being in a drone strike area, it means they "are probably up to no good."

Why, you ask, is the institutionalized vigilantism that killed 16-year-old American Abdulrahman al-Awlaki at least as problematic for society as the individual vigilantism that killed 17-year-old American Trayvon Martin? Because while the former comes at the hands of single extremists empowered by grotesque statutes like "Stand Your Ground," the latter comes as the official policy of the public's own government. Put another way, whereas the former can come from impulsive individuals acting extrajudicially under the protection of wrongheaded laws, the latter comes from the calculated debates, deliberations and decisions of a whole public-policy apparatus -- with the full force of that apparatus to mete out the extrajudicial punishment, and also protect itself from accountability.

In this context, then, Holder's dissonant words and deeds are revealing. The attorney general simultaneously using an NAACP speech to decry the unacceptable individual vigilantism aimed at Martin and yet using his office's power to promote the institutional vigilantism aimed at Abdulrahman al-Awlaki is a reiteration of a radical precedent. Effectively, the government is declaring that one kind of vigilantism aimed at children of color is not acceptable, but another kind is.

The administration's enunciation of such a radical precedent no doubt explains why in criticizing the preemptive violence against Martin and Awlaki, so many have drawn comparisons between Zimmerman and Obama.

It explains, for instance, why Coates compared Obama's drone-war rationale to Zimmerman's rationale for tracking Martin.

It explains why civil rights organizer Kevin Alexander Gray noted, "Obama did the same thing to (Abdulrahman al-Awlaki) as Zimmerman did to Trayvon Martin."

It explains why in the wake of the Zimmerman verdict UCLA historian Robin D.G. Kelley declared that Zimmerman's ideology is a "central component of the U.S. drone warfare and targeted killing" and that Obama's drone war is "little more than a form of high-tech racial profiling."

It explains why Dr. Cornel West referenced Obama's drone war in the wake of the Zimmerman verdict.

It explains why Gawker's Max Read wrote that we shouldn't think of Zimmerman's "behavior as aberrant" but instead see it as an individual "adopt(ing) the simple logic" of the institutional vigilantism behind the Obama administration's drone war.

It explains why when looking at the Martin and Abdulrahman al-Awlaki killings, Sheth wrote that "any critics of racism are surprisingly comfortable with a jingoist foreign policy, even when it includes the deaths of Pakistani and Yemeni toddlers."

And it explains why Black Agenda Report's Jemima Pierre invoked Obama's drone war by saying that "Our righteous indignation and anger over the Trayvon Martin murder has to stretch beyond our community to consider a global humanity — and especially the nonwhite victims of US militarism and racism."

All of these critics are echoing the point made most powerfully by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In his Riverside Church speech -- the one that modern efforts to "Santa Clausify" him attempt to ignore -- the civil rights leader said that we must see the fight to halt unnecessary violence and racism at home not as separate and distinct from the government's military policies, but inherently connected to them. Addressing critics who demanded that he not draw comparisons between the violence against minorities at home and the Democratic president's state-sponsored violence against people of color abroad, King said:

Many persons have questioned me about the wisdom of my path. At the heart of their concerns this query has often loomed large and loud: "Why are you speaking about the war, Dr. King?" "Why are you joining the voices of dissent?" "Peace and civil rights don't mix," they say. "Aren't you hurting the cause of your people," they ask? And when I hear them, though I often understand the source of their concern, I am nevertheless greatly saddened, for such questions mean that the inquirers have not really known me, my commitment or my calling. Indeed, their questions suggest that they do not know the world in which they live...

I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today -- my own government.

King's words were just as accurate back then as they are today. They are a reminder that we can make systemic progress against the kind of preemptive violence that took the lives of Trayvon Martin and Abdulrahman al-Awlaki. But they are also a reminder that we can only make that progress when the principles in Holder's NAACP speech finally apply to both individual vigilantism and the government's institutional vigilantism.

Without such a shift, Nasser al-Awlaki's desperate call for the government to explain his grandson's government-sponsored killing will not be the last of its kind; it will be simply be but one example of a tragically ongoing trend.

Shares