August 1960, Miami: a telltale bargain was struck between exiled Cuban politician Manuel Antonio Varona and organized crime leader Meyer Lansky. Lansky, the impresario of the Mafia gambling colony in Cuba since the 1930s, had owned Havana’s Hotel Riviera and the Montmartre nightclub and their fabulous casinos.

August 1960, Miami: a telltale bargain was struck between exiled Cuban politician Manuel Antonio Varona and organized crime leader Meyer Lansky. Lansky, the impresario of the Mafia gambling colony in Cuba since the 1930s, had owned Havana’s Hotel Riviera and the Montmartre nightclub and their fabulous casinos.

In Cuba, Lansky was known as the “Little Man” for his five-foot-four- inch stature, but his cold, hard eyes and intense demeanor were physical expressions of a man used to wielding power and getting his way. His dream of turning Havana into a tropical paradise for North American tourists had come true. Havana had a reputation for the best gambling and wildest nightlife in the Western Hemisphere in the 1950s. And since Lansky shared the Mafia’s profits with General Fulgencio Batista and senior Cuban army and police officers, that gambling paradise became the cornerstone of a full-fledged Cuban gangster state.

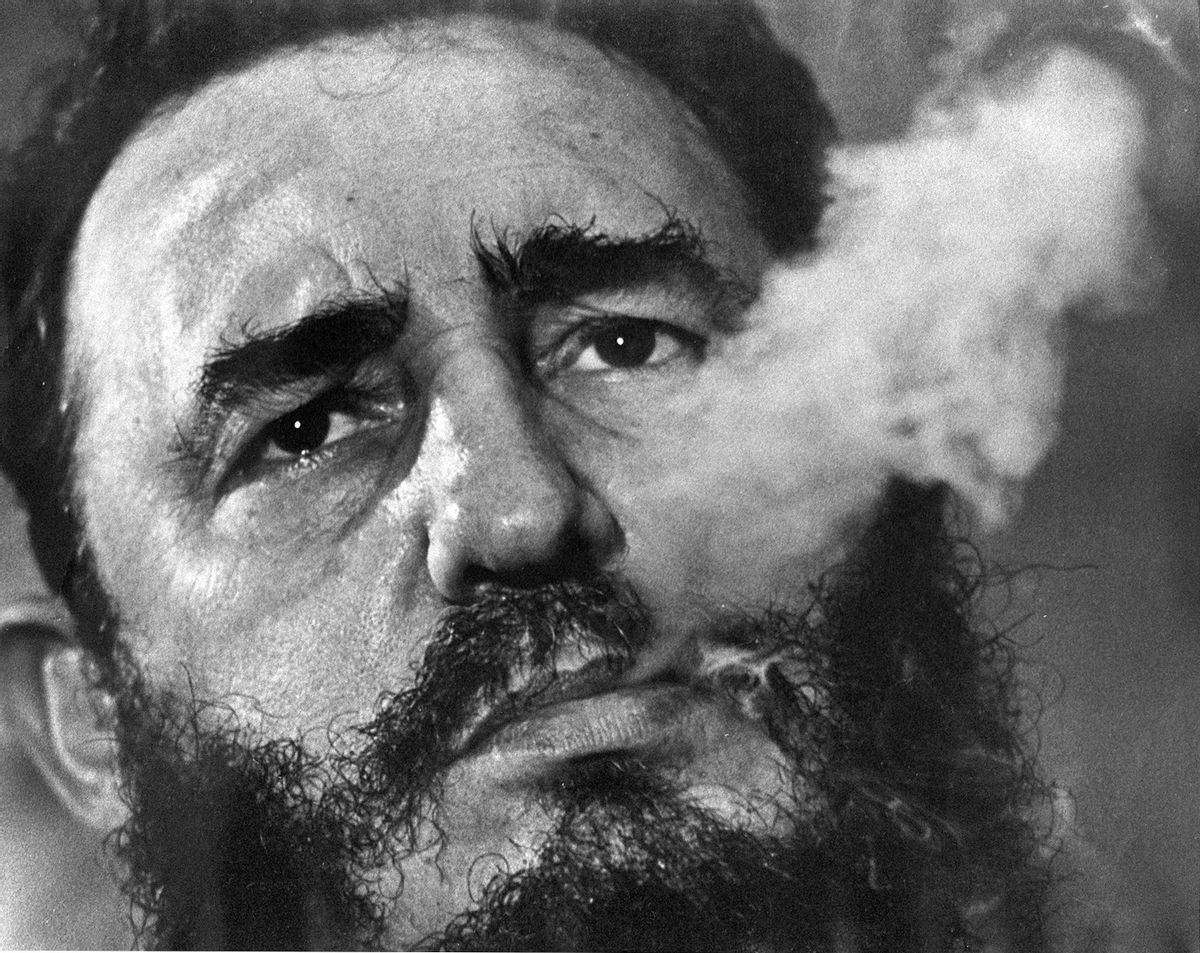

But when Fidel Castro’s bearded revolutionaries drove Batista from power on New Year’s Day 1959, Castro condemned the Mafia’s gambling colony for corrupting Cuban values, and shut it down. The Cuban Revolution brought down the curtain on the era of gangsterismo in Cuba.

In the meeting in Miami, Lansky offered Varona several million dollars to form a Cuban government-in-exile to replace Castro’s revolutionary regime. Lansky also promised to arrange a public relations campaign in the United States to polish Varona’s political image. In return, Varona, a stout man with heavy dark-framed eyeglasses, endorsed the Mafia’s single-minded objective: to reopen its casinos, hotels, and nightclubs in a post-Castro Cuba.

Several months before the Miami meeting, Varona, a leading member of the reformist Partido Revolucionario Cubano-Auténtico, had publicly broken with Castro. Ever since, he had been shuttling between cities in the Americas to confer with other anti-Castro Cubans in a bid for leadership of the Cuban counterrevolution.

Varona had been both prime minister and Senate president under Auténtico President Carlos Prío Socarrás. For their part, Prío and his brother Paco were closely connected to Lansky and Charles “Lucky” Luciano. In March 1952, Batista seized power in a coup d’etat (strike against the state), and Prío fled, leaving Varona to assume leadership of the Auténtico Party. But the Auténticos’ reputation as a reform party had been badly tarnished by the ties of its leaders to the Mafia gamblers. Varona himself had been connected with smuggling and kidnapping, and he kept pistoleros (political gunmen) on his payroll. A CIA memorandum reported, “[H]e maintained action groups at his service to force political decisions both in his [Camaguey] province and in Las Villas province where he was once provincial leader of the Auténtico Party.” Varona had good reason to accept Lansky’s offer. And so, in a remarkable act of political surrealism, the American Mafia, notorious for gangland murders and corruption of politicians, cleaned up the image of its Cuban partners in crime.

They hired the public relations firm of Edward K. Moss in Washington, D.C. Moss was a good choice for the job. Documents in his CIA file reveal that he had “longstanding connections” to organized crime in the United States. One report stated, “Moss’s operation seems to be government contracts for the underworld and probably surfaces Mafia money in legitimate activities.” Other CIA records reported that Moss worked for the Defense Production Administration of the Department of Commerce in the early 1950s.

Julia Cellini, who ran Moss’s secretarial services, came from a family of Mafia gamblers. Her brothers Edward and Goffredo were managers of the gaming rooms of the Casino Internacional and the Tropicana nightclub in the 1950s. Another brother, Dino, a close associate of Lansky, Santo Trafficante, Jr., and Charles “The Blade” Tourine, was a manager of the casino at the Sans Souci nightclub. His connection to Moss could be traced back to 1957. The Cellini brothers passed Mafia money—estimated at between $2 and $4 million—for Varona through the Edward K. Moss Agency, and Moss also solicited contributions from U.S. businesses for Varona. Moss was connected to other anti-Castro Cuban exiles in addition to Varona. He had met with Manuel Artime, leader of the Movimiento de Recuperación Revolucionario (MRR: Movement of Revolutionary Recovery), and discussed raising funds for him.

Moss also had ties to the CIA. When FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover reported that “[E]fforts are being made by United States racketeers to finance anti-Castro activities in the hope of securing gambling, prostitution and dope monopolies in the event Castro is overthrown,” in a December 31, 1960, memorandum to Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) Allen W. Dulles, the CIA already knew that Varona had met with the Mafia gamblers. That was because Moss had told the CIA’s Domestic Contact Division about his work for Varona. An August 25, 1960, CIA cable from JMASH in Mexico reported that Varona had “solicited funds [from] Las Vegas gamblers on a recent visit to the United States.”

According to a CIA memorandum, “Moss commented that he had been in touch with President-elect Kennedy’s staff so that they will be informed of his activities. His purpose in doing this is that he does not know as yet what the policy of the new administration will be for publicizing foreign activities on U.S. soil.” CIA Inspector General J. S. Earman acknowledged that the Agency had an “interest” in Moss, but said the CIA did not use him in Cuba operations.

But matters got even more complicated. While Varona was negotiating the terms of his partnership with the Mafia gamblers, he was also working out an arrangement with the CIA. Varona’s CIA security file indicates that he was “of covert interest” to the Agency in 1957. An October 1957 CIA memorandum stated, “Subject [Varona] is reported to be very close to one Carlos Prío Socarrás, ex-president of Cuba.” Varona frequently visited Prío at his residence in Miami at the Vendome Hotel.

Varona was given operational approval for “amended” use as an informant by the CIA’s Western Hemisphere Division on August 28, 1959. CIA headquarters recommended that “suitable controls” be used to keep Varona from “becoming an embarrassment to this Agency.” According to information in Varona’s CIA files, the Agency invited Varona “to the United States to set up an anti-Castro movement” in March 1960.

In June 1960, the CIA made Varona the general coordinator of the Frente Revolucionario Democrático (FRD) (Revolutionary Democratic Front), the CIA-sponsored Cuban government-in-exile. The CIA financially underwrote the FRD and the leaders of its member groups. Varona received a $900-a-month subsidy from the CIA beginning June 1, 1960.

Varona would also take part in a covert operation with the CIA and the Mafia gamblers to assassinate Fidel Castro. Thus, the circle of gangsterismo was squared. And an unnerving collaboration was revealed. Why would the CIA turn to gangsters? As CIA Director of Security Sheffield Edwards explained to the FBI: “Since the underworld controlled gambling activities under the Batista government it was assumed that this element would still continue to have sources and contacts in Cuba which could be utilized in connection with CIA’s clandestine efforts against the Castro government.”

In Washington, officials out of the intelligence loop on Cuba were unnerved when they learned how deeply the Mafia and their Cuban partners in gangsterismo were involved in the covert U.S. war in Cuba. Told by a “Washington businessman” about the Mafia’s subsidy of Varona, Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Special Operations Graves B. Erskine became alarmed. The retired Marine Corps general warned the administration that Varona’s ties to the gangsters could have disastrous consequences both for the FRD and the United States.

In a January 1961 memorandum, Erskine wrote, “The Washington businessman was quite concerned about the impact and potential propaganda value of this alleged connection of Tony Verona [sic] and the alleged racketeers in the event their organization is penetrated by Castro’s intelligence organization. He enjoys many contacts throughout Latin America and fears any propaganda stories by the Castro regime regarding such a relationship between Verona, American businessmen and Edward K. Moss’s activities would have a serious impact upon United States prestige throughout Latin America.”

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover alerted Attorney General Robert Kennedy to Erskine’s report in a January 23, 1961 memorandum. Hoover wrote, “We have received information to the effect that gambling elements in the United States have offered to distribute as high as two million to finance the anti-Castro operations of Varona and the organization he represents [Rescate], apparently in the hope of getting in on the ground floor should Castro be overthrown.”

The FBI was anxious about the political implications in the United States of Varona’s alliance with the Mafia. What if the Cuban Revolution was undermined, and the Mafia returned to the island to reclaim its gambling colony? Would U.S. public opinion turn against the White House and intelligence community?

A January 1961 FBI memorandum asserted that a “critical public reaction could be expected to follow the reactivation of large-scale gambling operations in Cuba by top hoodlums should Castro be overthrown.” Even the veteran spy William Harvey called the CIA’s covert collaboration with the gangsters a “hand grenade” waiting to explode. Harvey, who ran the CIA- Mafia assassination operation in 1962–1963, warned CIA Deputy Director for Plans (DDP) Richard Helms that there was a “very real possibility” that the Mafia would use its inside knowledge of the plotting to blackmail the CIA.

The baleful bargain struck by Lansky and Varona in Miami was a telling moment. Gangsterismo had migrated into exile in the United States along with tens of thousands of anti-Castro Cubans by August 1960. And it was to play a major role in the secret machinations of the CIA and Cuban exiles to overturn the Cuban revolution for years to come.

See more at Jacobinmag.com

Shares