IT’S ALWAYS FUN, when you’re among readers, to pronounce Martin Amis Britain’s greatest living novelist, then stand well back. As well as raising a grumpy harrumph from the grave of Kingsley Amis, the popular comic author and ambivalent spawner of a son who threatens to outlive his father’s reputation, you’ll probably set off a few puffs of nostril smoke. There aren’t many figures who can spark more passion among the UK literary establishment than Amis, who, 40 years into his writing career, still knows know to seduce his followers and put the wind up his foes.

IT’S ALWAYS FUN, when you’re among readers, to pronounce Martin Amis Britain’s greatest living novelist, then stand well back. As well as raising a grumpy harrumph from the grave of Kingsley Amis, the popular comic author and ambivalent spawner of a son who threatens to outlive his father’s reputation, you’ll probably set off a few puffs of nostril smoke. There aren’t many figures who can spark more passion among the UK literary establishment than Amis, who, 40 years into his writing career, still knows know to seduce his followers and put the wind up his foes.

Amis isn’t just the feted creator of darkly funny zeitgeist-surfing volumes of postwar British literature, such as London Fields, Money, and The Information. He has long been a forceful, compelling character in the playground of the UK’s intelligentsia, from his salad days as the cool, suave, luxuriously coiffed enfant terrible of Soho, holding court in the Pillars of Hercules bar with his great friends Ian McEwan and the equally commanding, if slightly less sexually swaggering Christopher Hitchens, to his current position as the 63-year-old man of letters who makes waves every time he dips his toes into the popular conversation.

His audacious tackling of subjects as tender as incest, infanticide, Islamism, and the Holocaust would have made him a controversial figure anyway, but Amis has also been on the wrong end of some proper showbiz gossip, including a furor over the dumping of his loyal agent (and the wife of pal Julian Barnes) in 1995, and the subsequent purchase of £20,000 of “American” teeth. He’s gotten used to being called a misogynist, a racist, a narcissistic show pony, a paranoid reactionary, a voyeur, a fantasist, and a genius. One imagines he reads each rant and rave with a cigarette in one hand, a quality Chablis in the other, and chuckles to himself imagining what The Hitch would have said about it all. Love him or hate him, his status as a pack-leading, groundbreaking master of language and ideas is a given.

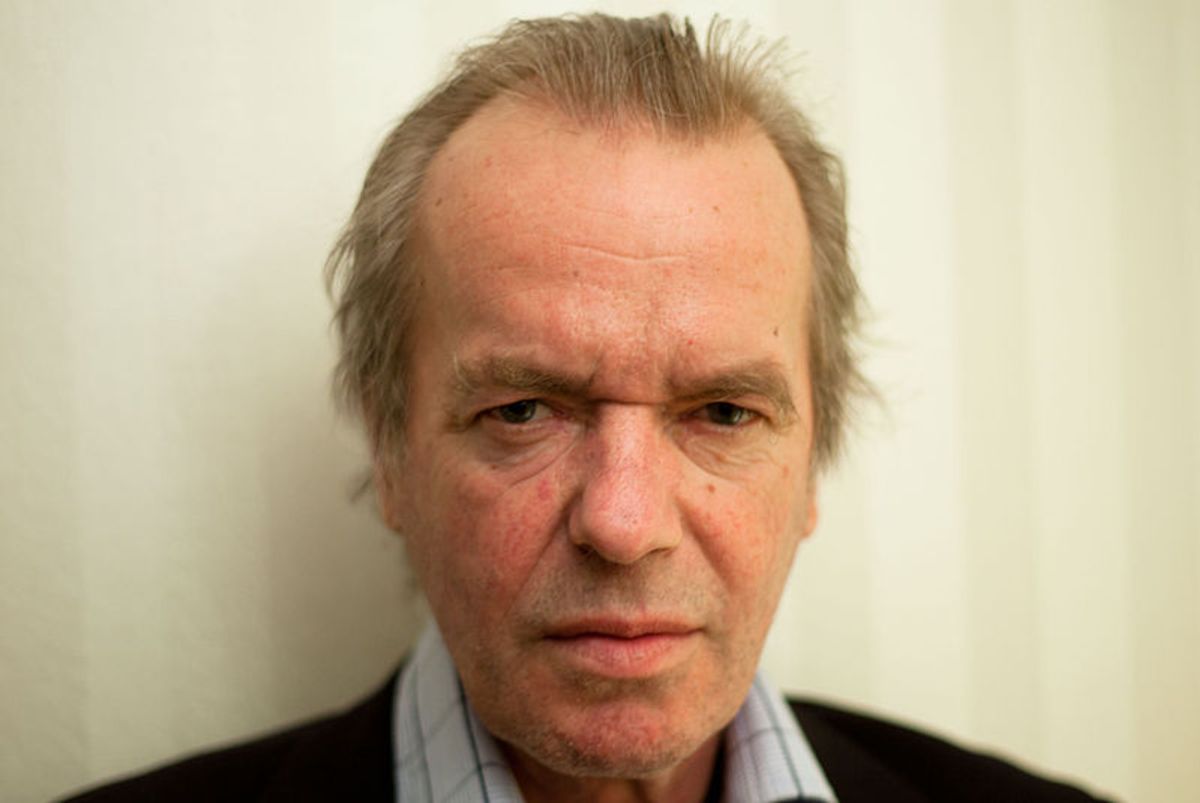

I met him on a blazing hot sunny day at a prestigious silver birch-lined address in London’s Notting Hill, ostensibly to talk about the paperback publication of his latest novel, the much-discussed Lionel Asbo (Richard Ford called it “brilliant and boisterous;” The New York Times declared it “a bad book”). He is still the most convivial host, ensuring the wine is in his guest’s hand before a seat is offered. He also retains his characteristic tasteful flamboyance, his grey hair still plentiful, his tanned skin set against a pastel pink shirt. And he still rolls his own cigarettes.

¤

JANE GRAHAM: You began writing seriously when you were relatively young, despite having been more interested in comic books up until your mid-teens. Did it ever occur to you that you might make a living doing something else?

MARTIN AMIS: Well, my father [Kingsley Amis] was a writer and it seemed natural to start writing in my late teens. I think it was good that I began when I was young and bold and foolish, otherwise I’d have become too self-conscious and aware of the weight of not having written anything yet. I think at that age everyone is looking inside themselves, processing their own thoughts, working themselves out — writers are just people who never grow out of it.

JG: Did it hang over you at first, being the son of such a popular writer in Britain? Or did you think you might capitalize on it?

MA: I started writing so young that I didn’t think about it much. I read his stuff and liked his stuff and was very conscious of being in the same tradition as him, the comic novel. Then it hangs over you a bit later on, especially in Britain anyway — it doesn’t matter so much elsewhere. But here, where he’s still a sort of presence — people get sick of you because you and your father have been around so long. They don’t separate you. It’s as if I was born in 1920. People think, Oh no, not that name again.

JG: Why do you think Kingsley made such a point of not being interested in your work?

MA: I think you’re irritated by your youngers and tend to be respectful of your elders. When I hear about some sensational new writer I sort of think, Shut up… you’ve got to be around for a long time before you can really say you’re a writer. You’ve got to stand the test of time, which is the only real test there is.

The Rachel Papers was probably the closest I got to his work, taking a few remarks from his first novel, Lucky Jim, turning them around a bit. I was certainly very aware of him but I wasn’t trying to be him. On the contrary, I was trying to be myself and to be original. And Clive James said, and Philip Larkin agreed: originality is talent. It’s the same thing. So you’re hoping you can find your own voice.

JG: Do you think, looking back, you were subconsciously trying to impress your father? Or anyone else in particular?

MA: I wasn’t trying to impress anyone other than my imaginary reader — which in my case is someone in their early 20s, around 25, someone just at the beginning of their reading years. But that’s a hazy idea. Really, you’re writing for yourself. You want readers; you love the reader. A great part of writing is hoping to make things as nice as possible for the reader — be a good host, have them put their feet up by the fire, pull up a chair, get out a good wine.

The writer who loves the reader always feels that; Nabokov would always give you his best chair. But there have been one or two writers who didn’t give a shit about the reader, like Joyce — partly because he had patronage, he didn’t need the reader to earn a living. And Henry James, who went off the reader in a huge way, which is why those last few novels became impenetrable. If you look at early James, he’s almost middlebrow, then you get The Ambassadors, this incredibly convoluted thing. Joyce and James became bad hosts: If you wandered into their house you wouldn’t be welcomed. You’d stagger around while they were in the kitchen making some vile concoction which might amuse you, but it would taste disgusting and eccentric.

JG: You went to live in New Jersey for a year when you were 9. Would it be too pat to suggest that you were immediately besotted with America and have never fallen out of love?

MA: It’s true I loved America right away and was excited by it. Then I had to go back to South Wales, and it all looked so small and dark and poky, and fridges looked very … small. I’m very grateful for that year in America. I think I speak American; I’m fluent in American. It’s very difficult to go from one side of the Atlantic to the other and trust your ear. Quite considerable writers can’t do it; they sound ridiculous; the words aren’t right. I think I imported some American rhythms into the prose as well as the dialogue, and in doing that maybe I did help open the English novel up a bit.

When I was in my early 20s, the English novel was very depressed: it was 225 pages on the ups and downs of the middle classes. The American novel was huge, like a Victorian novel. It’s weird the way fiction seems to go with power. When England was at the center of the world, our novels reflected that. Then after the Second World War it all shifted across the Atlantic and suddenly there were these great American writers, the great Jewish writers, and our writers were much smaller.

But the next wave was very good for the English novels, the Commonwealth writers coming home and giving us color. You can tell that the English got much more adventurous after that infusion, jumping around in time and place, not so tied to social realism, much freer. I think the English novel is now perhaps healthier than the American novel. The great Jewish writers have not been replaced. Roth has stopped — he was the last of the Mohicans.

JG: Roth famously reread his own novels, starting from the most recent, to “see if [he] had wasted [his] time writing.” Is that something you’ve ever done?

MA: No, it seems a real waste of time. My father did it later on and said they were all right. I’ve never done it, and I’m much less inclined to do it now. The past gets bigger but the future shrinks — it’s always onto the next thing. I don’t think it’s a bad idea to decide you’ve come to the end if you feel your powers are waning; it’s a response to feeling you have to dredge it out of yourself, whereas in the old days it was just coming up by itself.

JG: Were you the kind of writer who was constantly having ideas, scribbling on notebooks, waking up in the middle of the night and grabbing a pen?

MA: Yes. Does that still happen? No. I’m much more controlled than I used to be. I’ve lost a bit of inspiration but I’ve gained in technique. It’s more of a fascinating job than an absolutely giddy experience, as it used to be, and there’s more anxiety involved. You worry something’s wrong, and you don’t know what it is. If I were talking to my younger self, I’d tell him when that happens don’t sit at your desk sweating and swearing. Walk away. Your legs will take you back there once it’s fixed.

I wrote The Rachel Papers when I was 21, and the next ones came very punctually. I’ve had a few more missteps in recent years, in that I’ve gone on with things that have been no good at all, absolutely dead. The first draft of The Pregnant Widow was like that, dead as a doornail; I tried to do it autobiographically, and you can’t do that with something like the sexual revolution. But I went on and on until suddenly I just thought, This is dead. And it was nasty; I’d been working on it for over two years. I felt quite hollowed out for a week or two, then I saw a way to come at it differently, completely fictionalizing it. And God, that was a relief, getting away from autobiography to fiction; the freedom was bliss.

JG: You said recently you were concerned that literature was becoming too chummy, and you felt it had to retain its higher voice. Do you feel literature is a casualty of a general lean towards cultural democratization and the notion that art must be non-threatening and accessible to all?

MA: I’d say everyone is elitist, instinctively, in certain things, when it matters. You’re an elitist when you get on a plane: you don’t want anyone flying it. And you’re an elitist when you go to the doctor.

We only hear these arguments about things which can, supposedly, be stripped of hierarchy. Literature is very vulnerable to that because people just announce that the difficult stuff is off-putting and that’s the end of the argument. But I know when you become a writer you have to become an expert in words. I hate any sort of chumminess, any ingratiating “I’m just like you” stuff. You’re not consciously writing in an elitist way but you’re using words as they’re meant to be used and you know what they mean and you might even know what their origin is so you would never use a word against its original. You would never say “dilapidated hedge,” because dilapidated comes from "lapis" which means brick — you could have a dilapidated building but not a hedge. I can tell very quickly the level of expertise a writer has, and I like the experts. The instinctivists have their place — like John Clare, people who are hardly educated but still very talented. But I don’t think there are any instinctivist novelists.

JG: Do you think that ideally literature should shake people up, make them think about what they don’t know and what they should think about and investigate, that it should make them look words up in dictionaries and seek out other writers that might shed light on things?

MA: Yes, I do. There’s a morbid fear of dictionaries. But it’s more than that. You’re not trying to fill your reader with a thirst for actual knowledge, you’re trying to open up the universe a bit more for them. In Saul Bellow’s The Dean’s December there’s a dog barking: “‘For God’s sake open the universe a little bit more’ seemed to be the burden of the dog’s cries.” That’s what writers are trying to do. So when a good reader is finishing your book they will feel like the universe has a bit more color than it did before, and everyday on the street, they’ll see new things.

JG: So this popular idea that writing mustn’t put people off by being demanding or challenging — that presents a real threat to literature, and even more to poetry.

MA: The long, contemplative, essayistic novel is gone; there just isn’t an audience which would support it. Pretty complicated books which were very successful and got a lot of readers in the 1970s and 1980s — sayHumboldt’s Gift [by Saul Bellow], where there’s no real plot, the writer is just following his interests, and plot isn’t one of them — there just isn’t an audience for that anymore. The novel has become more streamlined and aerodynamic, and the arrow of development is much sharper than it used to be. It’s not that writers have directed it; they’re part of the modern world too. The rate of time has accelerated. And poetry’s under more threat than the novel. It’s very clear that what a poem does is stop the clock: we’re going to examine this moment; enter this epiphany and enjoy it with me. People say, "No, I haven’t got time."

JG: Talking of the democratization of culture, what do you think of Pippa Middleton becoming a contributing editor for Vanity Fair?

MA: Pippa Middleton…

JG: It’s Kate Middleton’s sister — Princess Kate.

MA: She’s going to do a column? That is shocking.

JG: Do you think it’s because the Americans have this love affair with our Royal Family?

MA: They’ve never had one of their own. It does intrigue them. But that is shocking.

JG: What do you think your old friend Christopher Hitchens would have made of it?

MA: Horrified, actually. He would have had words with Graydon Carter. Vanity Fair, it has been a home to greatness, literate and literary. Graydon must have bowed to pressure. It’s ridiculous.

JG: Your friendship with Hitchens was deep and enduring. When you first met — you were both in your early 20s — what did each of you offer the other?

MA: I used to correct his grammar; his punctuation was hopeless. I used to annoy him by saying he didn’t flower as a writer until 1989 when the wall came down. He’d also had huge traumas in his life. But it was really the wall coming down that freed him, the complete end of that ideology which he was quite wedded to. Writing of all kinds is an expression of freedom. If you’re beholden to an ideology or a line, you’re not free. So after that he went through the roof and started to gain a huge audience.

JG: When you were young men, at a party together, what differences were there between the ways you’d work the room?

MA: I remember we were at a party with about 20 people and he was leaving and he said, “I’ve got to leave, I’ll just make a brief pass at everyone then I’m on my way.” Then he’d go round, tongue in the ear of everyone present, boy or girl. I suppose I would be more focused on the women in the room, and not so interested in talking about politics. He wanted to talk.

One of the things that bound Christopher and me very strongly was we both had divorces. And we did things in parallel: got married around the same time, had kids about the same time, got remarried, and then had more kids. When you have someone hitched alongside you in life like that, it’s very bonding.

The week before he died, he was writing a piece. Christopher spent the last few weeks of his life in hospital. You get so you feel so fragile you don’t want to leave, it gets too much to handle, you want to be in a controlled environment, even though that’s sort of what killed him because he had three or four pneumonias and the last one … he was so thin, the immune system had gone. It’s this terrible narrowing of choices. It was so radical of him to die, so left-wing, so extreme. Most of us, maybe we get sick or have a shortened life, but I like to think he lived to about 75 really because he never went to sleep. His day was three or four hours longer than mine. So that’s a huge addendum to a life. He crammed it all in, perhaps too much.

JG: Did having children have a big effect on your writing?

MA: Oh yes. For one thing, I had this new cast of characters. I did a sort of horror baby in London Fields. Children are very comic.

I was quite broody for a while before they came. I’d got completely fed up with the single life. I wanted a new relationship between me and the world, and having children does change that. They’re the best thing, children. I felt from a very young age that these were the things on offer in life, and I wanted to have the life that involves bearing children. A negative example was Philip Larkin — no children, no marriage, no divorce, no war. My father was the opposite; he did it all. Not wanking in digs, that’s how Larkin put it. Which doesn’t sound great, does it?

It’s very nice to still have a 13 year old. It’s rejuvenating just looking at her. I find them fascinating. They’ll be gone soon. The empty nest — people have nervous breakdowns. I’ll be sad when they leave home.

A shorter version of this interview was published in The Big Issue.

Shares