What might the great 1970s feminists Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan have in common with a little-known cult movie in which a woman’s vagina suddenly develops a voice and embarks on a singing career? Chatterbox, a 1970s Sexploitation movie, plays with ideas of nonunitary selfhood, and examines issues of silence, sexual identity and social participation, while charting the protagonist’s desperate attempts to assimilate her ‘body-self’. The film’s director, Tom DeSimone, spent much of the 1970s working in the Exploitation/porn margins of the American film industry. He made several gay porn movies under the pseudonym of Lancer Brooks (How to Make a Homo Movie (1970)), and has had artistic forays into the camp horror genre, such as 1973’s Sons of Satan which features a gang of satanic homosexual vampires. In the 1990s, DeSimone moved into television work, directing the soap opera Acapulco Bay. While Breillat and Von Trier depicted menacing facets of a radical crisis of selfhood, with women’s genitals at its core, DeSimone’s 1977 film Chatterbox is, in its low-budget, kitsch approach, less intense and is not as much of an explicit take on themes which had been explored in Claude Mulot’s earlier porn movie Le Sexe qui Parle (Pussy Talk, 1975). The issues to which Chatterbox gives rise are important, focusing as they do on a particular ‘crisis’ of female identity which was articulated by second-wave feminists, and which motivated so many of the writers and artists I’m considering in this book.

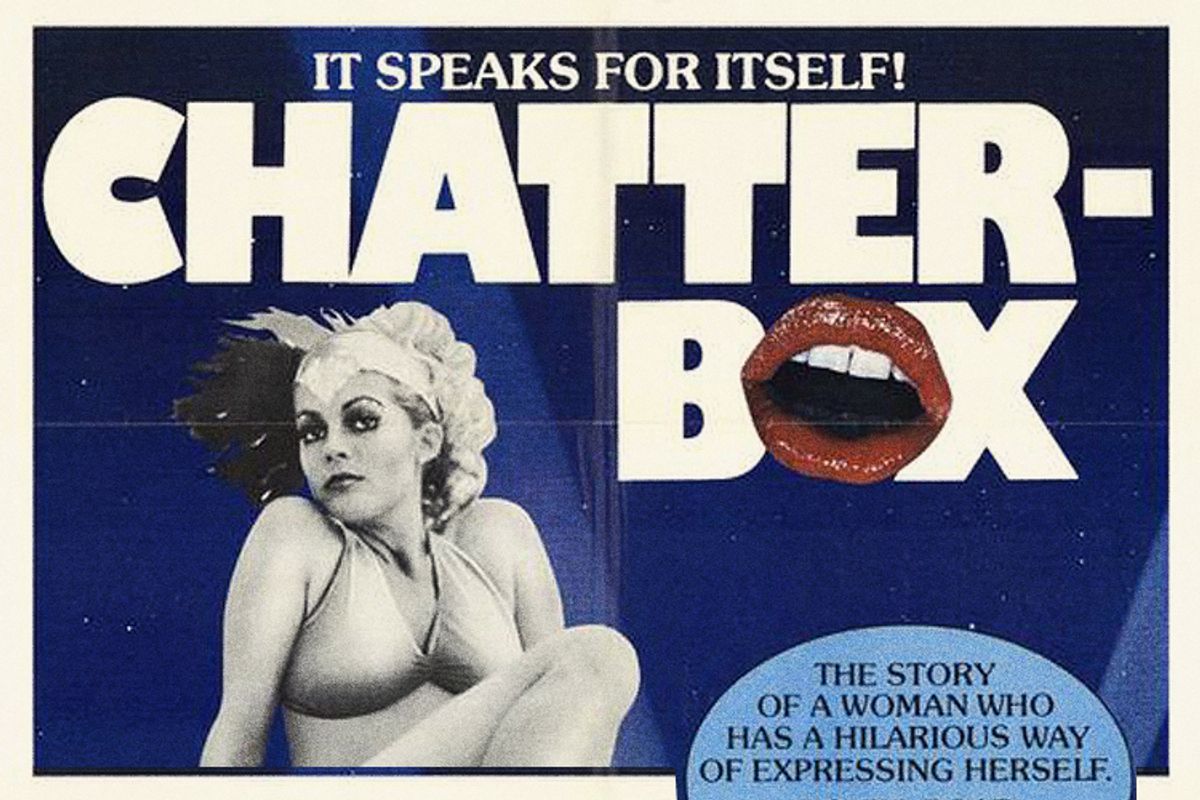

The movie’s aesthetic is less Breughel or Bosch, then, than Benny Hill, and the US poster makes quite clear the ‘Exploitation’ genre to which the film belongs: a woman (we later find out that she’s the film’s protagonist, Penelope) is dressed in a bikini and heels, her right leg drawn up in a pose which could be read as provocative or self-defensive. From her crotch comes a speech bubble which tells us that this is going to be ‘the story of a woman who has a hilarious way of expressing herself’, and that audiences will ‘roar when she sits down to talk!’ Above her is the movie’s title, the ‘o’ of Chatterbox being made up of a woman’s heavily lipsticked open mouth. ‘It speaks for itself!’ the poster exclaims, asking: ‘she talks with her what?’ The Belgian version of the film poster is even more explicit in that it dispenses with Penelope’s head and torso altogether, leaving instead a pair of stockinged legs balancing that lipsticked open mouth, the ages-old equivalence of lips and labia being quite clear. ‘Madam’, the poster asks, ‘how would you react if your “you-know-what” suddenly began to talk and sing?’ Penelope, star – or, crucially, as we shall see, co-star – of Chatterbox, is a self-effacing, socially naïve hairdresser whose vagina – later named ‘Virginia’ – does suddenly begin to talk and sing. Penelope seeks psychiatric help from a Dr Pearl who later becomes Virginia’s manager and the film, in a structure reminiscent of the porn features DeSimone also directed, unfolds as a series of vignettes. These tableaux are linked only by the central premise, and are occasionally punctuated by musical routines featuring songs such as ‘Wang Dang Doodle’ and ‘Cock a Doodle Do’. Viewers follow Penelope as she searches for romance, at the same time that Virginia is searching for sex and fame.

At the height of her celebrity, Penelope goes to a restaurant with her mother (who has with alarming alacrity set aside her concerns for her daughter once she realizes how profitable Virginia’s fame can be) and Dr Pearl and is quickly surrounded by fans. One says: ‘I can’t tell you how much I admire you, Virginia; you put Gloria Steinem to shame!’ ‘Thanks’, replies Virginia, ‘I put them all to shame!’ ‘Them all’ is an interesting concept in this context since a moment later a live TV crew bursts in on the restaurant, the host demanding of Virginia ‘Is there any truth to the rumour that Betty Friedan has challenged you to a debate?’ Any answer that there might have been is obscured as a priest is next to rush in, attempting, in a pastiche of the concerns we saw Robert Coover rather more darkly address, to exorcize Penelope. DeSimone’s conjuring up of Friedan and Steinem here casts light on the role of the film in terms of second-wave feminism. Virginia reverses Friedan’s credo that biology is not destiny so that Penelope’s destiny is fame or notoriety on tour throughout the United States as Virginia.

In her initial visit to Dr Pearl, the psychiatrist, Penelope tells him about ‘That foul-mouthed little beast [. . .] All she wants to do is have sex [. . .] But what about me? Am I supposed just to let her take over my life?’ This question taps directly into the cultural concerns informing the context of the film and of 1970s feminism. In finding an answer to Friedan’s slogan of isolation and despair – ‘Is this all?’ – that relies on an awakened and voiced libido, Penelope is radically disaggregated: her mind and body are at war. Her abjection is inescapable: to be human is at once to loathe the abject body and at the same time to need it, in all its gross physicality. Penelope epitomizes reticent domestic femininity; Virginia revels in sexual liberation. This liberatory impulse, however, in DeSimone’s rendition, is experienced by Penelope as a paralysing constraint. Paraded before the American Medical Association, ‘The 8th wonder of the world: Virginia the talking vagina!’ is in her element. The same cannot be said of Penelope, however, as she turns her head from the audience in horror and shame. Penelope is imprisoned after Virginia has sexually propositioned a traffic cop. Female sexuality is both spectacle and predicament: it runs counter to notions of liberation because Penelope is not in control. A female prisoner in the adjacent cell says to her, without realizing the irony of the statement: ‘You can button your lip!’ Bailed out of jail by a former boyfriend, Penelope is taken under Dr Pearl’s wing. Clearly an entrepreneurial Freudian, he has recognized the freak-show potential of Penelope’s unruly id and must persuade her to perform so that he can profit from her celebrity:

Up to now you’ve had a different notion about sex and about your sexual organs. You have been conditioned to feel guilty. Look. Virginia is simply that part of you that is speaking up to be heard. She doesn’t want to be just another anonymous organ, something that you never think about, like a pancreas. Nobody thinks about their pancreas. She is pure libido. All Virginia wants you to do is to enjoy yourself totally.

One of the many ironies of what Dr Pearl says here lies in his insinuation that Penelope’s conditioned guilt came from the suppression of her sexual identity, when every indication in the film is that once that sexual identity is expressed, Penelope experiences a very public guilt or humiliation on the showbiz circuit. After this point in the film, with Dr Pearl bent almost double in talking directly to Virginia, the camera replicates the sense that Penelope’s identity is becoming increasingly fragmented, by framing her body from the neck down as she melancholically walks the city streets at night. Later, Dr Pearl is very keen to continue to urge Penelope towards acceptance of Virginia as a mode of coming into being and maturity. ‘You may have come in here feeling like a frightened little girl’ he tells her, ‘But when you leave here everyone in America’s gonna know you’re a total woman!’ As Virginia excels by singing on television and then at venues throughout the States, the camera does take time to show the audience Penelope’s very evident discomfort: the more Virginia speaks, the more Penelope is railroaded into silence.

A lot has been written about the diversity and richness of women’s voiced identities; less on how silences can be powerful too. We need not read Penelope’s silence as emblematic of disempowerment, but as strength: a choice or resistance in the dilemma of coming into being. Feminist psychologist Carol Gilligan has argued that a woman’s silence signals a subordination which is most keenly felt at the onset of adolescence, that is, when sexual identity begins to be most strongly expressed, and when selfhood starts to be stifled. The problem with Gilligan’s concept is that silence can actually add to the anxieties felt by the subject whose choice it is to be silent, or who feels unable to speak. Gilligan’s reification of the individual’s ‘authentic voice’ is only of value or meaning when it is heard, but ‘authenticity’ of identity may reside in silence, too. Penelope inhabits the mode of being Virginia with varying degrees of defiance and unease. Indeed, the viewer cannot read the instability of identity – ‘You’re not our mother! You’re my mother!’ – as positive or playful. In this partitioning of self into public and private roles, the character experiences a profound conflict. As Mangogul’s female courtiers quickly came to realize, according to Diderot scholar Thomas Kavanagh, ‘the voice of the sex, speaking its mistress’s truth only on the condition she be reduced to pure object, is finally no different from those other voices of gossip and rumor making up the world of the Sultan’s court. It is the question of how we might respond to these voices that constitutes the real center of this text.’ So, how might we respond to quiet, resistant Penelope, who is at the mercy not only of her own body, but of exploitative hangers-on, too, as vociferous Virginia’s celebrity grows and grows?

In the incident with the TV crew in the restaurant, the evocation of Betty Friedan is informative in terms of that by-now familiar conflation of facial lips and labia. In her Feminine Mystique, Friedan had asked the ‘silent question’, bringing into language issues that she felt had for too long remained unspoken. Friedan wrote that:

The problem lay buried, unspoken for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban housewife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night, she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question, “Is this all?”

This is fundamentally the question which Penelope is asking in her pre-Virginia manifestation: ‘Is this all?’ In a sense, it’s the question which precipitated so many of this book’s concerns. Chicago’s ‘Womanhouse’ project, for example, as we have seen, in building tableaux such as the Menstruation Bathroom, exposed the ‘secret’, suburban, hellish life of so many women in the 1960s to 1970s. In Chatterbox, the TV host’s question about a Friedan/Virginia debate may not have been as confrontational as he hoped. Both Friedan and Virginia are struggling to allow women to experience a ‘real’ selfhood where sexual, social, professional and familial identities could be lived fully and with integrity. Penelope signals rebellion in her silence and refusal to participate in what her mother disparagingly terms ‘this moral revolution’ of mid-1970s America. The film, in its playfulness with voice, silence and selfhood, constructs a dilemma for the feminist critic as issues of agency and power surface. Speech is not wholly liberating for Penelope, but is a source of shame which lays her open to the greed and exploitation of those around her, even her mother. The relationship of Penelope to Dr Pearl and her mother is not unlike that of sex worker and pimp but, oddly (or, maybe, predictably given her lack of a voice), Penelope does not resist. In the final sequence, however, a transference has taken place, as it did in Coover’s play, when the ‘pricks’ of the Man and the Priest began to speak: Penelope’s vagina finds a soul mate as her boyfriend’s genitals beseech her not to commit suicide. On a cliff top, Virginia has pleaded of Penelope: ‘When you jump, keep your legs crossed’. Oddly, DeSimone’s Exploitation movie suggests a viable voice for women. It is a voice that’s concurrently silent and private, and voluble, sexual and public. As the director himself put it, ‘it was our intention to imply that Penelope and Virginia accepted each other’.

From "The Vagina: A literary and cultural history" by Emma L. E. Rees. Reprinted with permission from Bloomsbury Academic. Copyright © 2013.

Shares